It’s election time again, and – in some places, at least – education-related disputes are once again all over social media and the local news. Given that it’s rare for such a traditional, local issue to break through our current national insanity, some of you might be wondering just what it is all these teachers keep whining about and why no one can presumably fix what seem to be pretty basic concerns.

It’s election time again, and – in some places, at least – education-related disputes are once again all over social media and the local news. Given that it’s rare for such a traditional, local issue to break through our current national insanity, some of you might be wondering just what it is all these teachers keep whining about and why no one can presumably fix what seem to be pretty basic concerns.

None of these are intended as comprehensive or especially detailed, nor will they apply in every local variation of every argument. My hope, however, is that you’ll find them useful as a starting place for further research if you discover you care about those specifics, or as enough information to decipher those who ARE worked up and insist on talking about this stuff over and over and over and over…

Why are so many teachers opposed to testing? What’s wrong with accountability?

It can sometimes be difficult to narrow down exactly what it is states and taxpayers want public education to accomplish (not to mention the things we intrinsically value as educators). Prepare children for college, prepare them for the workforce, prepare them to be happy, personally fulfilled adults, teach them to be useful citizens of a voting republic, teach them character and personal responsibility, teach them to read, to think, to care, to problem-solve, to adapt, and give them grit, hope, respect for authority, and a deep personal sense of security and meaning in a fallen world.

Oh, and algebra – they need to know algebra.

Of these (and there are often more, depending on who’s in the state legislature that year), very few are easy to measure objectively, let alone assess via multiple choice questions. The most important ones certainly aren’t. How does an institution scientifically measure whether or not particular kids are more or less prepared for the profession of their choice in May than they were in August, or whether or not they better grasp the importance of informed voting, or even to what extent they’ve grown in terms of taking personal responsibility or refusing to crumble in the face of adversity?

Even the more traditionally academic stuff is hard to evaluate on a mass scale. Sit a kid in front of me and have them read a passage and discuss or explain it, and in ten minutes I’ll have a pretty good idea of their reading ability, processing strengths and weaknesses, etc. A multiple choice quiz over the passage, on the other hand, might tell me how well they manage short-term recall of mundane details, but isn’t very good at measuring whether they understand those details or can explain why they matter. It certainly gives no room for alternate approaches or explanations of anything important.

But it DOES give us what looks like an objective number of “right” and “wrong” answers. And it can be tallied by a machine. It measures the stuff it can easily measure – not the stuff we’d all largely agree is WAY more essential.

We can’t measure what’s important, so we prioritize what looks measurable.

In other words, your English teacher isn’t obsessed with the minutiae of grammar because that’s what makes great literature worth reading; he’s obsessed with grammar because that’s a random slice of reading and writing that we can kind of measure via multiple choice. His job performance isn’t measured by whether or not you become a better reader (whatever that might involve in your particular case) but on how consistently you and your classmates properly identify a form of speech chosen by a testing service from Wisconsin.

There are other issues – tests tend to measure kids’ socio-economic status far more consistently than they do anything actually happening (or not) at school. Some are racially biased in subtle but critical ways. Many of them just suck. But that’s all secondary to the larger issue – very little worth learning can be evaluated by Scantron.

Why don’t schools stick to the basics – the 3 R’s of Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic? What’s with the radical liberal agenda and all the touchy-feely stuff?

Most schools certainly want their kids to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic. Beyond that, we enter into the same dilemma reference above – no one can seem to agree on just what it is they want public education to DO. The same legislators who complain about Algebra scores devote endless legislation to requirements having nothing to do with academic progress. Local employers want kids to have specific job skills or foundational knowledge beyond the 3 R’s. And even parents generally hostile towards public education see the inherent value in kids being involved in sports, band, theater, etc. (The Home Schoolers are constantly suing to get their kid on the baseball team with a school-provided uniform.)

But beyond that, the most fundamental reason schools get involved in counseling, health care, clothes closets, basic nutrition, family services, restorative justice, pregnancy prevention, anger management, or whatever is because – spoiler alert – a pretty substantial number of kids show up to school not actually caring all that much about those Algebra scores. Or grammar. Or test scores. Or history.

Yes, we could just fail them all – but that’s not the motivator you might wish it were. For every kid hyper-focused on her GPA (“That quiz brought me down to a 104%!! Can I retake it!??!”) there are two who for whatever reasons couldn’t care less – or, if they do care in theory, aren’t able to translate that concern into daily choices.

We can call home, but there’s a pretty strong correlation between parents who are unavailable or otherwise not particularly helpful in motivating their kids and kids who are unmotivated. That’s not an excuse, or an attack, or grumpy-old-teacher-excuses – it’s just a fact of the gig.

So we try to figure out why. Usually it’s because they have other things on their minds. Stuff that can only be addressed via counseling. Or health care. Or restorative justice. Or –

You get the idea.

And yes, we also often genuinely care. Some of us are a bit touchy-feely. But even the most pragmatic and least dramatic among us would agree that if we’re going to get test scores up, or get them prepared for locally available jobs, or grow informed voters, or whatever, we often have to address whatever else is in the way before they’ll actually read that chapter about the New Deal.

What’s wrong with school choice? Vouchers? Charters? Doesn’t that money belong to the parents, who should be able to use it any way they think best?

This one can get messy rather quickly. I’m not sure I can adequately cover the many layers of interwoven issues while sticking to the goal of this particular ‘guide’. What I can do, however, is share the basic arguments you’re most likely to encounter.

The first and perhaps largest problem with “school choice” is the term itself. It suggests that any concerned parent can enroll their child anywhere they like – but they can’t. Even if your state gives you a voucher for what they’d have spent on your kid in a public school, even if you’re surrounded by quality options, the final decision about your child is entirely in the hands of the chosen institution. They can take him, reject him, or take him until he has a bad week then boot him without cause.

If you’re fairly affluent, white, with a stable family background and strong academic and behavior record, you’ll probably be fine. Lots of schools want you on their rosters – and websites – and scoring summaries. For many families, this isn’t a bug so much as a feature – the primary benefit of “school choice” is that it allows kids from families “like us” to get away from kids “like them.” We can’t mandate loving your neighbor, but neither can we completely avoid their existence or influence, or somehow escape impacting them in return.

The second problem is the impact on public schools. As private institutions skim off their top choices, your local school now has less money and an increased percentage of high-needs students. Whatever economies of scale were making it possible to give the entire range of them a decent education before are reduced dramatically – it’s difficult to fire two-thirds of a bus driver or maintain a building at three-quarters what you did before. In short, the need increases while resources are diverted elsewhere.

Note that these are NOT individual resources – that’s wordplay. Public resources – tax dollars, paid by everyone for the benefit of the whole. The ‘social contract’ on which society, even red-white-and-blue society, is built. I don’t pay state and local taxes so that MY kid gets a decent education; I pay them so I can live in a society filled with people who have a decent education, obey laws agreed upon by a reasonably coherent populace, work as part of a semi-rational economy, and partake in a civilization which knows its own history, can read and write, and considers basic math and science when making major decisions.

That brings us to the third problem, which is that most of these other school “options” aren’t held to the same standards or expectations as public schools. That makes rhetoric about “competition” rather disingenuous.

In public schools, science must be treated as a real thing. History has established standards determining whether or not it’s legit. Teachers have to pass state certifications. Right-wing talking points to the contrary, we’re not all human refuse just making it up as we go because we don’t want to get real jobs.

Public schools have to at least attempt to educate students in a publically agreed-upon and legislatively mandated curriculum while observing endless protections, prohibitions, guidelines, and red tape. We have to take ALL of them, whatever their issues, whatever their needs, whatever their circumstances – including those left without a school when their charter closes mid-year or their private religious school kicks them out for getting pregnant or coming out as gay.

The final problem is that “choice” doesn’t actually improve education in any meaningful ways. Most private schools aren’t demonstrably better than public schools at anything measurable (see issues with that above) when comparing students from similar backgrounds and characteristics. Charter schools overall perform worse. Public schools don’t get “better” due to competition; the very idea suggests they aren’t really trying very hard to begin with and need something to “motivate” them to try to teach those kids up real good this time!

In short, the entire premise of school improvement via competition is a deception built on pruned statistics and rhetorical smoke and mirrors. Maybe it should work. Maybe in some circumstances it could work. But so far, taken as a whole, it doesn’t work.

Feel free to suggest other topics for the guide below, as well as linking to your favorite blog posts from around the web which dive into some of these issues in greater detail. And vote, dammit.

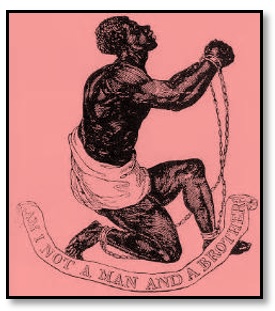

1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery.

1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery. Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.

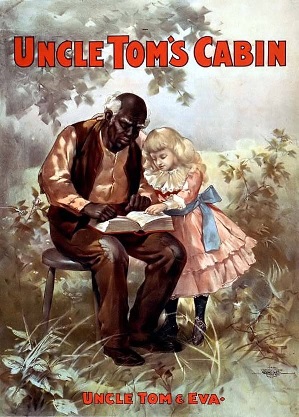

Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.  Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.)

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.) John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…”

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…” From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address:

From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address: Forgive me #edutwitter, for I have sinned. It’s been two weeks since my last post, but months since anything, you know… good.

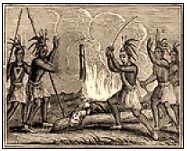

Forgive me #edutwitter, for I have sinned. It’s been two weeks since my last post, but months since anything, you know… good.  1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers. I don’t like to lie to my students. I try not to, but it’s not always easy. Sometimes it’s literally required by the folks signing my paycheck, creating what we in the teaching business call “a dilemma.”

I don’t like to lie to my students. I try not to, but it’s not always easy. Sometimes it’s literally required by the folks signing my paycheck, creating what we in the teaching business call “a dilemma.” Lie #1: You can be anything you want to be if you really set your mind to it.

Lie #1: You can be anything you want to be if you really set your mind to it. Lie #2: Appearance doesn’t matter – it’s only what’s inside that counts.

Lie #2: Appearance doesn’t matter – it’s only what’s inside that counts. Lie #3: This {insert stupid required school thing, probably state-mandated, always done in the most annoying, time-consuming way possible} is very important for all these reasons we’re about to give.

Lie #3: This {insert stupid required school thing, probably state-mandated, always done in the most annoying, time-consuming way possible} is very important for all these reasons we’re about to give.