I’ve written about the Blaine Amendment before in the context of Oklahoma GOP shenanigans a few years back. This time around, I’m looking to go a bit ‘bigger picture’ and give it a brief chapter in “It Followed Her To School One Day,” which might actually be finished before summer. Below is the first draft of that chapter.

The final product will be tighter (this one’s too long) and less ranty-ravee about things.While I’m not going for detached and boring in the book, I will shoot for something a bit more balanced and accessible to the average reader. This is not an ethical decision so much as capitalistic lust. I mean, let’s be honest – conservative dollars spend the same as liberal dollars, and they have WAY more of them, so no sense alientating them right out of the gate. Keep it subtle, so they can be offended and horrified after it’s too late to return it.

Here with you, however, my Eleven Faithful Followers, I can share my unfiltered wisdom with spices and color intact.

What’s In A Blaine?

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun.

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun.

The term dates back to Representative James Blaine of Maine, who pushed for a national amendment along those lines during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The movement failed at the federal level, but the idea was picked up by numerous states in subsequent years – some voluntarily, and some as a requirement for entering the Union as the nation continued to expand. While innocuous enough as written, these various Blaine Amendments have something of a rocky historical past. “Non-sectarian” in the 19th century was often used euphemistically to promote anti-Catholic bias. (If Protestant was normal and proper, then “sectarian” was by implication any deviation from that – with emphasis on “deviant.”)

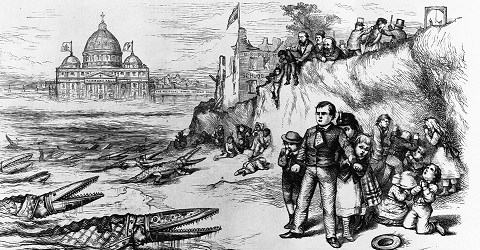

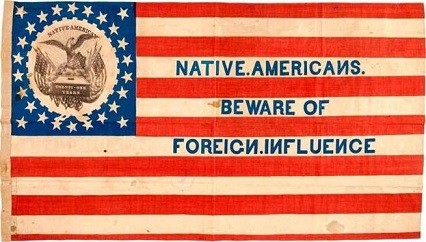

To be fair, it wasn’t just Catholics who were suspect. Your average 19th century WASP didn’t think much of anyone or anything not brazenly Protestant, at least in form and rhetoric. Catholics, however, were a particularly prominent and successful example of dangerous foreign influences and cultish ideologies trying to strip “real Americans” of their only-recently-established eternal birthrights to the continent. They were in many ways the Muslims of their era – technically entitled to their beliefs, and most wanting the same basic things for their homes and families as everyone else, but still viewed with suspicion because obviously their religion meant their loyalties must truly lay elsewhere, far across the globe in places most Americans still can’t locate on maps. (Nor should they have to, given that anything not in America is by definition un-American and besides-who-prays-to-dead-people-that’s-so-weird-am-I-right?!?)

Needless to say, American Catholics were relieved when a generation or two later the nation realized the true enemies of freedom were immigrants, labor unions, and women who wanted to vote.

In any case, there’s history suggesting that these Blaine Amendments weren’t always so much about keeping schools secular as keeping them vaguely Protestant. Variations on the idea date back to the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party of the 1840s and 1850s.

Make America Know-Nothing Again

The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname.

The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname.

The true irony of this self-inflicted moniker was, of course, entirely lost on them.

The Know-Nothings as a political party vanished after the Civil War, but their toxic sentiments, like the smell of desperation and last night’s cigarettes, proved difficult to wash out of Uncle Sam’s sparkly coat. One of these sentiments was the desire to “protect” public schools (relatively new entities, even in the late 19th century) from pagans, atheists, “Muhammadans,” and of course, Catholics.

There was no federal Department of Education at the time, and state-level governments weren’t always overly concerned with how local districts were run. It wasn’t unusual for students to be required to read from the King James Bible, sing hymns, or pray, and teachers often taught through the lens of Protestant doctrine. Not surprisingly, Catholic Americans didn’t love paying taxes to support public schools that openly reviled their faith and forced their children to perform Protestant rituals. Some began pushing for equitable state support for Catholic-flavored schools as well – an idea Protestants found horrifying. What a vile betrayal of our freedom of religion! The First Amendment was supposed to build a wall protecting us from stuff like this!

Thus, the Blaine Amendments – at least in some cases. In others, history suggests a genuine effort to balance the roles of church and state to the benefit of society as a whole. That’s the trick with politics and history. People (especially politicians) claim all sorts of motivations for things, both good and bad, and there are often a combination of sentiments and goals all mushed together in any slice of legislation or political rhetoric. Sometimes later generations can tease out the underlying motivations with confidence (the Eleventh Amendment, the Oklahoma Land Run); other times historians are left to grapple with conflicting information and informed speculation in their efforts to address hows and whys (the Salem Witchcraft Trials, the endurance of “Deadliest Catch”).

A century and some change later, most Americans’ opinions of the Blaine Amendment have little to do with its origins and more to do with their personal religious druthers and the extent to which they feel persecuted and downtrodden by the presence of other belief systems in the society around them. Nevertheless, the origins of these state provisions have become a primary focus of those wishing to overturn it. The argument is that these Blaine Amendments are expressions of religious bias and discrimination, something Protestants in this country have generally favored but must now modify based on shifting dynamics and a shared cause – “the enemy of my enemy is still a heretic, but whatever.”

Historical Motivations

The Supreme Court has not always been consistent when it comes to factoring in historical contexts. In its defense, as discussed above, it’s sometimes difficult to unravel the motivations or intentions behind legislation or specific constitutional verbiage. The Second Amendment, for example, was clearly written with the assumption there would be no standing army in the United States and that local militias were thus essential to “provide for the common defense.” The amendment has nevertheless entrenched itself in the American psyche and longstanding jurisprudence far beyond its original purpose. Whatever else might have been intended, it certainly never came anywhere close to “individuals should be allowed a reasonable variety of weapons for personal protection or hunting but nothing designed primarily to fight in wars like, say, a militia might use.” And yet, over time, the meaning has been allowed to evolve based on changing times. Lawyers and judges still shamelessly wrestle with each word and tortured comma as if they don’t know perfectly well what an incoherent mess it is. The text and practical application has become the priority; the history of the amendment is now merely a curiosity.

More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them.

More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them.

Other times, however, the motivation behind a law or government action suddenly matters, at least to interested parties. In cases involving holiday displays, moments of silence, or public installments of the Ten Commandments, the Court generally weighs the context and history of the legislation or decision-making and considers intent along with the actual text or result. The infamous “Lemon Test” begins by examining the purpose of a governmental action. The updated “endorsement test” first expressed by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor asks what a reasonable observer would perceive as the intentions of the government in a given situation – again bringing backstory into the foreground. In short, sometimes the history matters. (That’s why politicians have become so adept at signaling supporters as to what they’re really trying to accomplish with a particular piece of legislation while coating their official rhetoric in slippery nonsense; they don’t want their own words and true goals to be used to overturn pet projects.)

Despite the obvious benefits of this approach, it can be tricky business. As Justice Rehnquist expressed in his dissent in Stone v. Graham (1980), when enough legislators and constituents support something they believe has legitimate value and meets constitutional guidelines, it’s presumptuous for any court to step in years later and impugn their motivations in order to invalidate their choice

In other words, if something’s unconstitutional in its text and application, that’s one thing, but if it’s only unconstitutional because the courts know what people in the past were really up to, well… that’s potentially a bit more complicated. Which brings us back to the Blaine Amendment. Amendments. Whatever.

The dominant majority of WASP Americans in the late-19th century were certainly distrustful of Catholics (and Jews, and Chinese, and Freedmen, and transcendentalists, and DC Comics movie adaptations, and GMOs, and immunizations, and… you get the idea). It’s not universally clear that Blaine Amendments were solely the product of this bias, and states retained substantial wiggle room when it came to spending state funds on state interests through the end of the 20th century– with or without Blaine in the discussion. It was substantially weakened, however, by Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), a landmark voucher case in which the Court determined that vouchers could be used at religious schools whether the state wanted them to or not. It seemed to be holding its own in Locke v. Davey (2004), however, when the court decided that the state of Washington was not violating the Free Exercise Clause by excluding theology majors from a state scholarship program.

Room For Playgrounds In The Joints

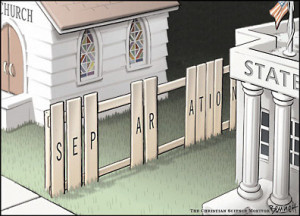

Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.

Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.

In Espinoza v. Montana (2020), the Court danced about on Blaine’s grave and urinated on its tombstone – despite never quite declaring it dead. This was another “school choice” case in which the majority determined that states had no right to exclude religious schools with overtly religious missions from programs paid for with public tax dollars. While religious schools were “churches” for purposes of shielding them from most forms of government oversight, they were suddenly “schools” again when it was time for checks to go out, as long as some veneer of “parent choice” was involved in the mix. In Montana’s case, the mechanism was a “scholarship program” in which donors could contribute to “scholarship funds” in exchange for tax credits. The organizations running the “scholarships” would then award them to families to use at private schools of their choice.

Unlike in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, there was little discussion in the Court’s opinion regarding mechanisms for ensuring funds were equitable – that is, that they actually covered most of the cost of tuition at the private school where they were applied, making it possible for families of limited means to participate alongside those for whom the “scholarship” was simply a nice bonus. The Court expressed little concern with whether or not the institutions in question were focused on providing a quality education across the curriculum or simply promoting their own religious dogma, suggesting that it wasn’t really their place to distinguish between schools that happened to be religious and religious institutions that happened to call themselves schools. The roundabout “scholarships” and “tax credits” system was sufficient to eliminate the need for state oversight of such things in the name of the Establishment Clause, while the Free Exercise Clause meant any effort to limit the use of public funds based on religious status was outright verboten.

The state could either indirectly support everyone who wanted to play, whatever the actual results or applications of the funds, or cancel the program altogether.

And yes, this time the Court called out Blaine by name as it yanked out the IV and held the pillow over its face. It stopped short of declaring Blaine irrevocably deceased, but… let’s just say things aren’t looking too good overall for the whole “church-state separation” thing. Whether that’s a positive or a negative depends on how much you actually paid attention in history class.

RELATED POST – Worth A Look: Locke v. Davey (2004)

RELATED POST – To Sleep, Perchance To Sue

We’ve been looking at Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the case most often cited when I’m researching vouchers and their constitutionality.

We’ve been looking at Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the case most often cited when I’m researching vouchers and their constitutionality.  Here’s a fun little game. Go to

Here’s a fun little game. Go to

As discussed

As discussed

This is where I wonder if the lack of actual

This is where I wonder if the lack of actual  Ohio’s program is constitutional because of all of the non-religious alternatives promoted by the state. If parental choice means a majority of kids end up in religious schools, that’s fine – as long as it’s the result of true choice. That means a variety of accessible options, both religious and non, public and private.

Ohio’s program is constitutional because of all of the non-religious alternatives promoted by the state. If parental choice means a majority of kids end up in religious schools, that’s fine – as long as it’s the result of true choice. That means a variety of accessible options, both religious and non, public and private.

This addresses the second prong of the “

This addresses the second prong of the “

The Oklahoma GOP has for some time now held unchecked control of both the State Legislature and the Governor’s chair. Voters have handed them the keys, a 12-pack of Keystone, and encouraged them to have their way with the state. You’ve no doubt noticed the resulting prosperity trickling down all around you.

The Oklahoma GOP has for some time now held unchecked control of both the State Legislature and the Governor’s chair. Voters have handed them the keys, a 12-pack of Keystone, and encouraged them to have their way with the state. You’ve no doubt noticed the resulting prosperity trickling down all around you.

Actually, this being Oklahoma, I should clarify further. “Are vouchers an effective way to provide a better education for a greater variety of students in a fiscally realistic way?” That’s how they’re promoted ‘round these parts, but I’m not at all convinced that’s the actual goal. (See earlier disclaimer about the humble guy with a blog.)

Actually, this being Oklahoma, I should clarify further. “Are vouchers an effective way to provide a better education for a greater variety of students in a fiscally realistic way?” That’s how they’re promoted ‘round these parts, but I’m not at all convinced that’s the actual goal. (See earlier disclaimer about the humble guy with a blog.)

But you can’t legislate community buy-in, and you can’t mandate teacher satisfaction or require people to stay in the profession. The public wouldn’t pass bonds to pay for stuff, and district school boards wouldn’t make hard choices about cuts. Add school-board drama, conflicts over school closings and program cuts, and the ever-looming issue of racial equity, and despite many good people mostly pursuing what they thought was right, it just… they couldn’t…

But you can’t legislate community buy-in, and you can’t mandate teacher satisfaction or require people to stay in the profession. The public wouldn’t pass bonds to pay for stuff, and district school boards wouldn’t make hard choices about cuts. Add school-board drama, conflicts over school closings and program cuts, and the ever-looming issue of racial equity, and despite many good people mostly pursuing what they thought was right, it just… they couldn’t…