A few weeks ago, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister tweeted something about cursive being part of the revised ELA standards. Being me, I responded semi-snarkily about Morse code or quill pens or such. It was friendly, but I was oddly annoyed in a way I wasn’t quite ready to confess.

Joy being Joy, her response was diplomatic and included links to relevant research. In the exchange, I also somehow managed to antagonize a number of dyslexia advocates (er… they’re not advocating FOR dyslexia – you know what I mean), so… I let it go.

Conflict wasn’t my goal, for once. I like Joy, and some of my best friends are, um… dyslexic, I guess.

But… why did I even care? What was up with that? And then I remembered. All of it.

I graduated from high school in 1985 completely unprepared for the academic and personal expectations of a legitimate university. I was ‘smart’ enough, but immature and underexposed to challenge. My high school’s “Honors” program was mostly a few pull-out sessions a week in which we did brain teasers and ‘leadership skills.’ I wasn’t exposed to anything like AP or IB until I was actually teaching, many years later.

I dropped out of the University of Tulsa after five semesters, having failed a number of classes and lost most of my academic and other scholarships for lack of… doing much.

It was over a decade before I went back. By that time I was married (which wasn’t going particularly well), had two small children, and had realized that neither my band nor my job were going to make me rich, famous, or fulfilled. In short, my life kinda sucked.

In the midst of this madness, my then-wife said something for which I am still thankful all these years later. “You should consider teaching. You’re already full of ****, so most people love you, and you tell a pretty good story as long as it doesn’t have to be accurate or appropriate. Why don’t you teach history?”

I didn’t have any better ideas, and what better way to offset my own bad choices and misery than bringing down as many others as possible? Ruining young lives, 153 at a time!

Best decision of my life.

Still working almost full time, taking out ridiculous loans I could never repay, two small children at home with a decent mother but unhappy spouse, I returned to school.

Initially, I was rather… discouraged by the caliber of people on the introductory education path. Dear god, no wonder schools were in such trouble. What was I doing?

Over time, however, those initial masses were culled a bit and things weren’t so awful. I hated the theory and the touchy-feely stuff, but I loved the history – despite those classes being particularly difficult for me. I knew so little about… anything.

Two and a half years of full-time school, work, kids, rocky marriage, no money, smothering in-laws, and personal dysfunction. There were some great individuals and good moments, but I messed up more than I didn’t. I was slightly above average academically, but a train wreck at life skills and direction.

And yet, I made it.

I graduated with a respectable GPA, given how I’d begun all those years before. I met the best people and earned the right honors, and was becoming potentially useful to the universe.

Time to take the state test. The big, scary, ‘teacher certification’ exam.

Everything from this point forward is colored by emotional memory. For those of you who are facty thinkers, please understand that for some of us, REALITY is a series of EXPERIENCES which may or may not exactly correspond with purely objective recall.

I can’t swear to the details, but I am certain as to the version forever burned into my psyche.

The test back then was big and comprehensive and scary. I remember trying to study from Oklahoma History textbooks while glazing over in disinterest, and cramming on World Cultures and Economics about which I still knew next-to-nothing, barring a few interesting centuries in Europe and how to effectively juggle overdraft fees.

As to the pedagogy and touchy-feely, well… I’d just have to fake it as best I could. As my first wife had suggested, I was fairly gifted at being “full of ****.”

I arrived at the testing center nervous, but ready to dive in. I remember a locker for my personal belongings, and some guidelines I had to read. Then came the clipboard.

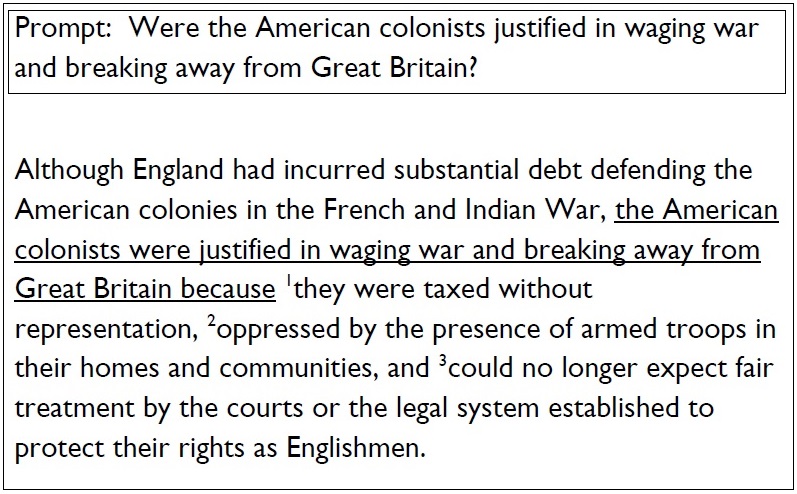

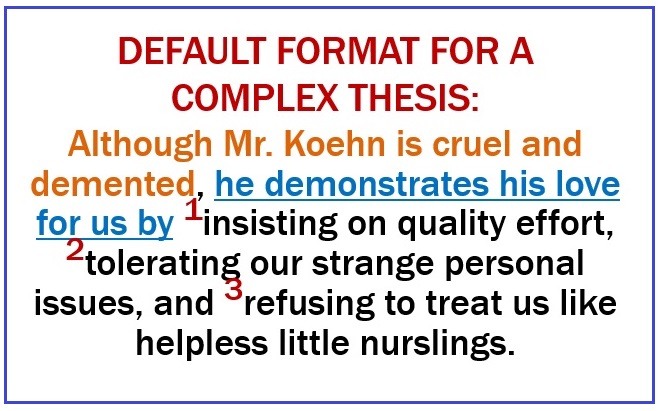

“Read and copy the following certification of something or other IN YOUR OWN HANDWRITING and sign and date at the bottom.” I hadn’t planned on this – a long list of formalities I’d have to copy in a foreign script before I’d even be allowed to begin the actual test.

The timed test. The one determining if the past two-and-a-half years of my life had been worth it. The one potentially ruining everything. The one I was already worried about, despite weeks of stressful preparation. The one for whom the clock was already ticking.

I hadn’t written in cursive since elementary school. I could read it, but I can listen to others play the piano without being able to reproduce the process. I’d printed – efficiently – throughout high school, retail, and college. I’d long-since stopped even thinking about it.

I walked nervously to the desk and asked the lady… see, I don’t… could I…?

No. Those were the rules. That was the system.

So I started laboriously trying to copy this… this… required certification. In my memory it’s easily a page long, but I don’t know how technically true that was.

I do know that at 30 years of age, with two kids at home and a wife who didn’t like me much but who’d devoted two-and-a-half years to getting me through school, after leaving a good-paying job (which, granted, I hated), I was shaking. The frustration, and helplessness, and anger, and… how stupid I felt.

SO stupid. What was I thinking – that I was going to change the world? I couldn’t even copy the $%@&ing certification. Angry stupid. Impotent stupid. It overrode rational thought.

Twenty years later, I’ve handled worse without it killing me. It seems melodramatic in retrospect. But at the time, it felt like the worst thing that had ever happened to me. It took me forever to get through, and I don’t even remember the rest of the day or the actual testing.

I was telling my (new, hopefully permanent) wife about this after the Twitter exchange referenced above, and the emotions from that day ambushed me, rather unfairly. I nearly lost my suave – weird, given that I hadn’t thought much about it in the nearly twenty years since.

There’s a lesson here about assessment and whether we’re actually measuring what we claim – no one warned me that working with teenagers hinged on my ability to write cursive under pressure.

There’s probably a ‘grit’ lesson of some sort as well – I mean, I finally copied the damn thing in some butchered version and took the actual certification tests. I even passed – to the chagrin of my poor students each year.

Mostly, though, it’s just a horrible memory that still stirs up things I don’t like to think about and feelings I don’t like to feel – helpless, stupid, angry things which I try to channel a bit more productively these days.

None of which Joy Hofmeister could possibly know, and for which she can certainly not be held responsible. She wasn’t Superintendent then – she probably wasn’t even through high school yet.

So… sorry I was snippy. Hope I hid it well. I promise, though, that I won’t argue about cursive anymore. It turns out I have a few lingering… issues on that subject.

Not that anyone could ever tell.