Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About Tiananmen Square

Three Big Things:

1. In 1989, Tiananmen Square, Beijing, was one of many sites across China where citizens marched, chanted, and otherwise protested government corruption; they demanded reforms and protection of basic human rights.

1. In 1989, Tiananmen Square, Beijing, was one of many sites across China where citizens marched, chanted, and otherwise protested government corruption; they demanded reforms and protection of basic human rights.

2. Government response was brutal, especially at Tiananmen Square; foreign reporters and photographers managed to smuggle out stories and media of the Chinese military abusing and executing protestors.

3. One especially poignant video (and the still photo encapsulating it) shows an unknown individual waving his arms at a tank, then climbing up and shouting at the operators before being rushed off by equally unknown figures. This individual has since been remembered as “Tank Man.”

Background

By June of 1989, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had been in power for forty years, following decades of civil war against the Kuomintang (KMT), or Nationalist Party. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was declared in 1949 with Mao Zedong as its unquestioned first-among-equals; he ran the nation in ways both brutal and strange.

The KMT, led by Mao’s nemesis Chiang Kai-Shek, retreated to Taiwan, where they established China Classic, and remained (in the eyes of the west) the officially recognized government until 1971. Despite being virulently anti-Communist, the KMT weren’t exactly “good guys” in this tale. Taiwan was under martial law for nearly forty years, led by a government in perpetual paranoia over potential spies or Commie sympathizers. In 1971, the United Nations finally relented to reality and gave the KMT’s seat to the PRC.

Within a few short years, China Major – the big, red part we all know and love today – went from a “Cultural Revolution” in which anyone insufficiently excited about Chairman Mao’s “Little Red Book” was assaulted, humiliated, or simply made to vanish, to welcoming President Nixon and celebrating the “thawing” of relations with the west. For the next few decades, the U.S. and China took turns pretending to care about basic human rights while building a complex and mutually profitable relationship. China purchased a bunch of America’s debt and allowed U.S. industries partial access to one of the world’s largest markets, while the U.S. became a massive importer of Chinese goods and created an endless supply of movies for them to illegally copy. For better or worse, the two became (and remain) inseparably bound.

China craved economic growth and global legitimacy, seeking the ideal mix of market forces and “Chinese Socialism” while reclaiming some of their historic status in the eyes of the rest of the world. They loosened their grip on the little people, hoping they’d behave on their own if they knew what was good for them, and even wrote themselves a new constitution, adopted in 1982. It was super-socialist, to be sure, but also rather ambitious in terms of protecting personal liberties.

And Then 1989 Happened

On April 15th, 1989, a popular politician by the name of Hu Yaobang died (he was 73 and had a heart attack – nothing nefarious). Hu was rebellious and relatively progressive, popular with idealists and college students – the Bernie Sanders of his day. Students and others took to the streets to mourn his passing, which inevitably transitioned into rather blunt criticism towards those still alive and in power. Soon their demonstrations became protests – against corruption, against the party’s mistreatment of Hu, and whatever else came to mind along the way. And they spread.

On April 15th, 1989, a popular politician by the name of Hu Yaobang died (he was 73 and had a heart attack – nothing nefarious). Hu was rebellious and relatively progressive, popular with idealists and college students – the Bernie Sanders of his day. Students and others took to the streets to mourn his passing, which inevitably transitioned into rather blunt criticism towards those still alive and in power. Soon their demonstrations became protests – against corruption, against the party’s mistreatment of Hu, and whatever else came to mind along the way. And they spread.

Government response was inconsistent. Sometimes the powers-that-be power cracked down; other times, they seemed open to discussions. Protestors were unpredictable as well. It’s complicated enough to be clear what you’re against; far trickier to consistently project what you’re for. There were hunger strikes, rallies, some violence, and lots of yelling.

Always with the yelling, those protestors.

By June 4th, the government had had enough. After several strong editorials warning the masses to wrap it up and get on with their carefully managed lives, troops were sent in to disperse the protestors. Sometimes they made arrests, other times they simply fired into the crowds. This was not, however, a tense situation which somehow erupted into violence; this was methodical military action carried out according to orders from above.

Tanks then rolled into Tiananmen Square – site of one of the largest demonstrations. Protestors who refused to move or who simply couldn’t get out of the way were rolled over – several reports say multiple times, so their remains could be literally hosed into the sewers rather than taken away and buried. Clearly China was sending a message about just how seriously all of this new “freedom” was to be taken – and they were willing to sacrifice their own citizens and a certain amount of reputation in the eyes of the world in order to do it.

The official death toll was 200 – 300. The Red Cross estimated 2,700. Recent memos between British and U.S. officials suggest an alarmingly specific 10,454 – dead at the hands of their own government.

China did attempt some damage control with the international press. Reporters had their equipment seized, their hotel rooms trashed, and their well-being threatened over the words and images they were determined to send back to their respective outlets. But It turns out that pesky liberal media can be quite heroic sometimes, no matter what flavor of corrupt, arrogant power tries to shut them down. So… go free press, and all that.

That is why – against all odds – we have images like this:

“Tank Man”

It’s not at all clear who this was. He may have been a 19-year old student named Wang Weilin, or maybe not. He was eventually pulled away – but by whom? Government agents? Sympathetic protestors trying to protect him? He may have been imprisoned, tortured, or killed, or he may have simply faded into obscurity and gone on with his life. We’ll probably never know.

Here’s what we do know. He had absolutely no reason to think those tanks were going to stop.

They hadn’t, the day before. As he stood there defiantly, he could hear the gunshots and screams of other protestors paying for their defiance. It’s not clear where he came from or how he ended up alone in Tiananmen Square, facing off with destruction, but he quickly became an international symbol of… something. Defiance, maybe. Or freedom. Human rights, or perhaps the entire Tiananmen Square protest and resulting crackdown. To some extent, what his action symbolized is in the eye of the beholder. We’re certainly unlikely to ever know what he thought it meant.

Aftermath

“Tank Man” didn’t stop the tanks. We can’t reasonably connect his actions to the saving of any lives. At best, he slowed down one segment of a long, complex series of horrors for about five minutes.

Nothing changed in China’s policies, tactics, or narrative as a result of the protests, either, in Tiananmen Square or anywhere else. All references to the event are scrubbed from Chinese internet searches and prohibited in all Chinese sources. If “Tank Man” lived past his asymmetrical showdown, it’s extremely unlikely he had any idea that his actions had been viewed or discussed by anyone not there that day. Even if he’s alive and well today somewhere in China, odds are he has no idea that he’s an iconic photograph or world history talking point.

China quickly moved on, as if the massacre never happened. In 2001, they joined the World Trade Organization. In 2008, they hosted the Olympics. Their economy continues to grow steadily in the 21st century, and at times China appears ready to play nice with the rest of the world.

Other times, not so much.

Human rights abuses are still a substantial concern, but in the modern age of omnipresent news, never-ending tragedy, and ubiquitous corruption, the rest of the world is far less focused on specific problems – in China or anywhere else – than we perhaps used to be. Besides, most of the nations who’d have once taken issue with such things are making quite a bit of money from their relationship with China – as a customer, a supplier, or merely an open door to foreign investments and corporate expansion.

Still, the name “Tiananmen Square” and the image of “Tank Man” still resonate decades later, clearly speaking to something in our collective human experience. Such intangibles, however, are the purview of psychology, sociology, or maybe even mythology. In terms of history, the protests happened, then were removed. The fate of “Tank Man” we simply don’t know, and probably never will.

The Xhosa were (and are) a major cultural group from the Eastern Cape. The land was fertile and there were plenty of fresh water sources for their cattle – which, as it turns out, were rather important to them. Like the Zulu, they were descended from the Bantu who centuries before had migrated from the northwest. Xhosa is still one of the most-spoken languages in Africa, and the native tongue of Nelson Mandela, Bishop Desmond Tutu, and the Black Panther.

The Xhosa were (and are) a major cultural group from the Eastern Cape. The land was fertile and there were plenty of fresh water sources for their cattle – which, as it turns out, were rather important to them. Like the Zulu, they were descended from the Bantu who centuries before had migrated from the northwest. Xhosa is still one of the most-spoken languages in Africa, and the native tongue of Nelson Mandela, Bishop Desmond Tutu, and the Black Panther. Since the mid-17th century, the Xhosa, like the rest of Southern Africa, had been forced to accommodate European settlers on the Cape – first the Dutch, then the British. The Dutch Boers were especially problematic. Staunch Calvinists, they believed themselves quite literally chosen by God and rarely hesitated to transgress on Xhosa territory. In turn, the Xhosa raided Boer settlements for (what else?) cattle, and hostilities erupted regularly.

Since the mid-17th century, the Xhosa, like the rest of Southern Africa, had been forced to accommodate European settlers on the Cape – first the Dutch, then the British. The Dutch Boers were especially problematic. Staunch Calvinists, they believed themselves quite literally chosen by God and rarely hesitated to transgress on Xhosa territory. In turn, the Xhosa raided Boer settlements for (what else?) cattle, and hostilities erupted regularly. The homestead was understandably hesitant to embrace this revelation, so Mhlakaza returned with the girls to the site of the visitation. The strangers would only communicate through Nongqawuse (which perhaps should have been a red flag) but Mhlakaza was nonetheless convinced one of the spirits was, in fact, his deceased brother, and embraced the prophecy wholeheartedly. Mhlakaza sent word to the other chiefs, and soon the entire nation was talking. Even King Sarhili sent trusted family members to investigate; soon he, too, was officially a believer.

The homestead was understandably hesitant to embrace this revelation, so Mhlakaza returned with the girls to the site of the visitation. The strangers would only communicate through Nongqawuse (which perhaps should have been a red flag) but Mhlakaza was nonetheless convinced one of the spirits was, in fact, his deceased brother, and embraced the prophecy wholeheartedly. Mhlakaza sent word to the other chiefs, and soon the entire nation was talking. Even King Sarhili sent trusted family members to investigate; soon he, too, was officially a believer.

Nevertheless, with so much gold came more Uitlanders – ambitious individuals as well as foreign companies with the resources and know-how to manage difficult extraction. The Transvaal government made it difficult for newcomers to vote or otherwise fully participate in society, which didn’t bother those only interested in quick profits but antagonized the British to their ideological cores.

Nevertheless, with so much gold came more Uitlanders – ambitious individuals as well as foreign companies with the resources and know-how to manage difficult extraction. The Transvaal government made it difficult for newcomers to vote or otherwise fully participate in society, which didn’t bother those only interested in quick profits but antagonized the British to their ideological cores. The Jameson Raid reinforced to the Boer the importance of sticking together – supporting one another while constraining the Uitlanders. Tensions continued to build for several more years and eventually the British resorted to a more traditional approach and began building up troops along the border. In October of 1899, President Paul Kruger issued an ultimatum demanding they withdraw.

The Jameson Raid reinforced to the Boer the importance of sticking together – supporting one another while constraining the Uitlanders. Tensions continued to build for several more years and eventually the British resorted to a more traditional approach and began building up troops along the border. In October of 1899, President Paul Kruger issued an ultimatum demanding they withdraw. The Anglo’s perceived brutality severely damaged their standing in the eyes of the rest of the world as well as provoking outrage and protests back home. The war became increasingly unpopular as it continued to drag on, prompting the British to offer increasingly generous terms to the guerillas. Those determined to fight to the bitter end became known as Bittereinders (I’m not even making that up), while those who accepted reconciliation were labeled Hensoppers – literally, “hands-uppers.”

The Anglo’s perceived brutality severely damaged their standing in the eyes of the rest of the world as well as provoking outrage and protests back home. The war became increasingly unpopular as it continued to drag on, prompting the British to offer increasingly generous terms to the guerillas. Those determined to fight to the bitter end became known as Bittereinders (I’m not even making that up), while those who accepted reconciliation were labeled Hensoppers – literally, “hands-uppers.”

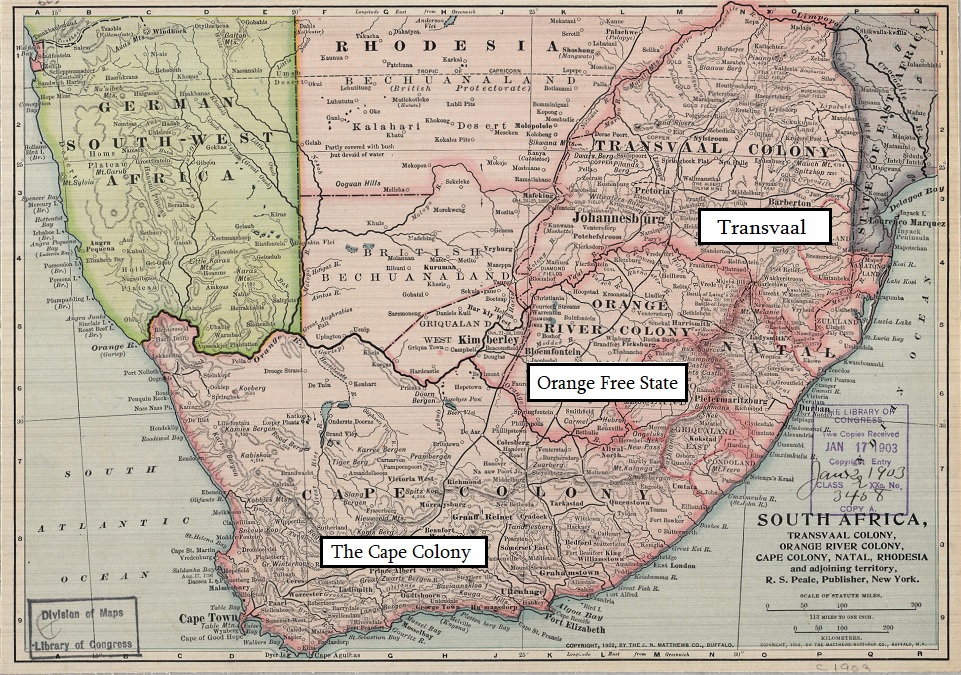

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of.

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of.

Things are getting serious when you start wishing locusts on people. No one should wish for locusts. Wild animals eating your bread, sure – but locusts? That’s just harsh.

Things are getting serious when you start wishing locusts on people. No one should wish for locusts. Wild animals eating your bread, sure – but locusts? That’s just harsh.

“Feudatory” is a funny word. It probably works better in the original tongue. The root, of course, is “feudal” – as in “feudalism.” It conjures up images of western European lords and serfs, trying to avoid the Plague while men in tights play recorders and bald clergymen harrumph about, gardening and copying books by hand.

“Feudatory” is a funny word. It probably works better in the original tongue. The root, of course, is “feudal” – as in “feudalism.” It conjures up images of western European lords and serfs, trying to avoid the Plague while men in tights play recorders and bald clergymen harrumph about, gardening and copying books by hand. I mean, I can’t prove the Mongols talked and swaggered like bad movie mobsters in early 20th century Chicago, but you can’t prove they didn’t – and in today’s world, that makes my interpretation way truer than yours.

I mean, I can’t prove the Mongols talked and swaggered like bad movie mobsters in early 20th century Chicago, but you can’t prove they didn’t – and in today’s world, that makes my interpretation way truer than yours.