I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating.

I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating.

Below and in Part One, I’m sharing the drafts of two of earliest cases likely to be included. Both involve little children not saying the Pledge of Allegiance because they believed it violated the Word of God to do so. Both cases were pursued as “freedom of religion” issues, but both were resolved on “free speech” grounds more than anything “wall of separation”-ish. In the second, the Court completely reversed itself only three years after the first – so that was unexpected.

Recap of the Story So Far…

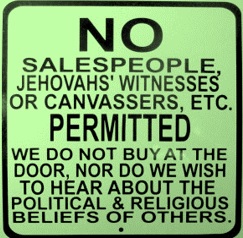

Jehovah’s Witnesses took (and take) literally the Bible’s exhortation to “have no other gods before me.” After experiencing persecution in Germany for not pledging their allegiance to the Fuhrer, leaders of the Witnesses discouraged saluting or reciting oaths to any national symbol – including the American flag. Many public schools in the U.S. required students to salute the American flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance, hoping this would foster patriotism and a sense of civic duty and community in the youth. When young Jehovah’s Witnesses refused, they were punished with expulsion.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses insisted this was a violation of religious liberty. In 1940, the Supreme Court disagreed. “Sorry this offends your beliefs,” the Court ruled, “but national unity is a valid goal of schooling and the law didn’t target your people on purpose.” (I’m paraphrasing.)

Part Two: West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943)

After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous.

After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous.

Only a few decades before Gobitis was the first “Red Scare,” in which all things foreign or strange were suspected of undermining the American way of life and required hostile, or even violent response. A decade after the Court’s reversal in Barnette, Congress would launch hearings into the “Communist infiltration” of government, publishing, and the entertainment industry, resulting in hundreds – possibly thousands – of loyal citizens losing their livelihoods and enduring ostracism by friends and neighbors.

In other words, being the “other” in the 20th century wasn’t simply a matter of some suspicious looks or hostile tweets. It meant you weren’t safe just going about your business, no matter how hard you worked, how many taxes you paid, or how devoted you were to your faith and your family. The Jehovah’s Witnesses weren’t Communists, of course – but they were weird and often unpleasant. So… close enough.

A Free, Public Re-Education

Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different.

Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different.

Following the Court’s decision in Gobitis, West Virginia and other states upped their citizenship game and began requiring more intensive public school courses in history, civics, and Constitutional studies. They wanted there to be no doubt about the meaning of traditional American values, like “recite what we tell you and salute the symbols we choose or pay the price!” The West Virginia Board of Education issued a statewide resolution requiring the Pledge and flag salutes at all public school events; refusal to participate would be considered “insubordination” and dealt with harshly. The statute quoted extensively from the Majority Opinion in Gobitis by way of justification.

So… Ouch.

West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school.

West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school.

Think what you like about mandatory oaths of fealty, this is a nice touch, statutorily-speaking. It rubs salt into the stripes on their backs, but in a “What? We’re just trying to help!” kind-of-way.

Marie and Gathie Barnette were Jehovah’s Witnesses who quietly refused to swear allegiance to anyone or anything other than the Lord their God. They were expelled, and once again the Witnesses began legal proceedings, despite the Court’s decision only a few years before.

Cases like the Barnettes’s don’t magically appear before the Supreme Court. They’re filed in the appropriate local court first, then potentially appealed up through the hierarchy. Barnette v. West Virginia State Board of Education (the names are reversed because initially the Barnettes were the plaintiffs) began in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia and was heard by a three-judge panel in 1942.

District Courts are generally expected to follow the precedents set by those up the food chain – the Supreme Court or, lacking clarity from D.C., the closest District Court of Appeals. There are many cases involving issues not specifically addressed by the higher courts, of course, and from time to time you’ll get a rogue judge or two who go against the grain, but normally a case like Barnette would have been fairly straightforward, given its similarity to Gobitis a few short years prior. Clearly the Court would decide for the schools and everyone could go home.

Only they didn’t.

“Ordinarily We Would Feel Constrained…”

In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days:

In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days:

Ordinarily we would feel constrained to follow an unreversed decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, whether we agreed with it or not. It is true that decisions are but evidences of the law and not the law itself; but the decisions of the Supreme Court must be accepted by the lower courts as binding upon them if any orderly administration of justice is to be attained. The developments with respect to the Gobitis case, however, are such that we do not feel that it is incumbent upon us to accept it as binding authority. Of the seven justices now members of the Supreme Court who participated in that decision, four have given public expression to the view that it is unsound, the present Chief Justice in his dissenting opinion rendered therein and three other justices in a special dissenting opinion in Jones v. City of Opelika…

There is, of course, nothing improper in requiring a flag salute in the schools. On the contrary, we regard it as a highly desirable ceremony calculated to inspire in the pupils a proper love of country and reverence for its institutions. And, from our point of view, we see nothing in the salute which could reasonably be held a violation of any of the commandments in the Bible or of any of the duties owing by man to his Maker. But this is not the question before us…

Courts may decide whether the public welfare is jeopardized by acts done or omitted because of religious belief; but they have nothing to do with determining the reasonableness of the belief. That is necessarily a matter of individual conscience. There is hardly a group of religious people to be found in the world who do not hold to beliefs and regard practices as important which seem utterly foolish and lacking in reason to others equally wise and religious; and for the courts to attempt to distinguish between religious beliefs or practices on the ground that they are reasonable or unreasonable would be for them to embark upon a hopeless undertaking and one which would inevitably result in the end of religious liberty.

There is not a religious persecution in history that was not justified in the eyes of those engaging in it on the ground that it was reasonable and right and that the persons whose practices were suppressed were guilty of stubborn folly hurtful to the general welfare…

That last bit echoes Justice Stone’s dissent in Gobitis. Justice Robert H. Jackson, who will write the Majority Opinion in Barnette, explores the theme from a different angle, but just as clearly.

Nine Justices, One Hundred and Eighty Degrees

The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved:

The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved:

The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials, and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. One’s right to life, liberty, and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.

It was important to the decision that the children’s abstention didn’t interfere with the rights of those around them to go right ahead and say it and wasn’t disruptive in and of itself:

The freedom asserted by these appellees does not bring them into collision with rights asserted by any other individual. It is such conflicts which most frequently require intervention of the State to determine where the rights of one end and those of another begin. But the refusal of these persons to participate in the ceremony does not interfere with or deny rights of others to do so.

Nor is there any question in this case that their behavior is peaceable and orderly. The sole conflict is between authority and rights of the individual…

The non-disruptive element matters in this context because “disruption of the learning environment” is often sufficient to allow authorities to restrict behaviors in a school setting which would typically be protected in the larger adult world. (A generation later, the non-disruptive impact of black armbands worn to protest the Vietnam War will be central to the Court’s protection free speech for high school students in Tinker v. Des Moines, 1969.)

In essence, the Court supported the concept of encouraging patriotism and national unity; it rejected the suggestion by the State that the best way to do this was mandatory rituals – especially when they violated the conscience of those involved.

Aftermath

Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well.

Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well.

Even then, the Court often drew a broad distinction between protecting belief and allowing religiously-driven behavior which violated state or local law. This “belief-action doctrine” was most clearly expressed in Reynolds v. United States (1878), a case involving the 19th century’s most vilified religious group, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints –more popularly known as the Mormons.

At issue was the practice of polygamy, and whether or not one’s sincerely held religious convictions could override man’s prohibitions against a practice steeped in history, practiced peacefully among consenting adults, and harming no one. This being the U.S., the answer was inevitable: of course not, because eewwwww!

Laws are made for the government of actions, and while they cannot interfere with mere religious belief and opinions, they may with practices…

Suppose one believed that human sacrifices were a necessary part of religious worship, would it be seriously contended that the civil government under which he lived could not interfere to prevent a sacrifice? Or if a wife religiously believed it was her duty to burn herself upon the funeral pile of her dead husband, would it be beyond the power of the civil government to prevent her carrying her belief into practice?

So here, as a law of the organization of society under the exclusive dominion of the United States, it is provided that plural marriages shall not be allowed. Can a man excuse his practices to the contrary because of his religious belief? To permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself. Government could exist only in name under such circumstances.

The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s.

The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s.

The Court’s reversal in Barnette didn’t eliminate suspicion or violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses, but it did at least remove the illusion of federal sanction for such actions, which dropped in both number and severity. America had other things to worry about, and over time the Witnesses started making some effort to be less aggressive and alienating whenever possible to do so without compromising their beliefs.

And in case you’re wondering, they still don’t say pledge their allegiance to anyone’s flag. Nor do they have to.

RELATED POST: The Jehovah’s Witnesses Flag Cases (Part One)

RELATED POST: “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation

Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…”

Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…” I recently finished

I recently finished  In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective.

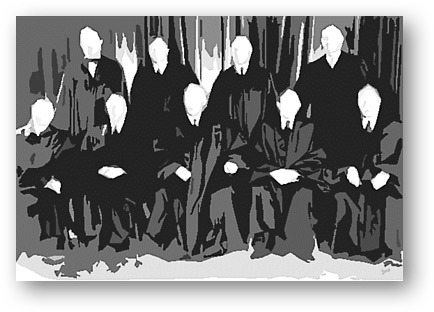

In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective. We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court.

We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court.