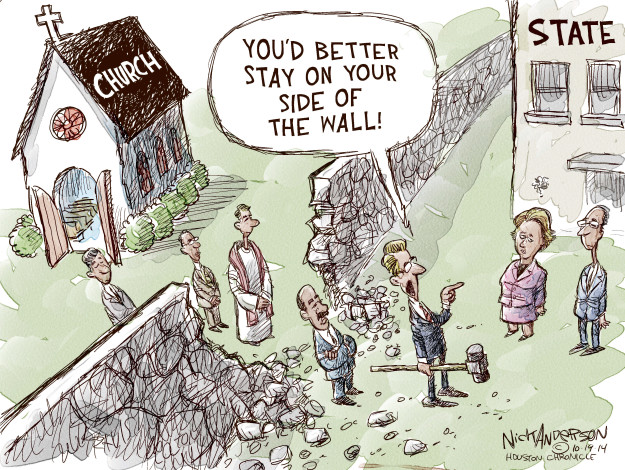

A “Hall of Separation”

That’s a horrible title and I wish I could stop thinking it’s not.

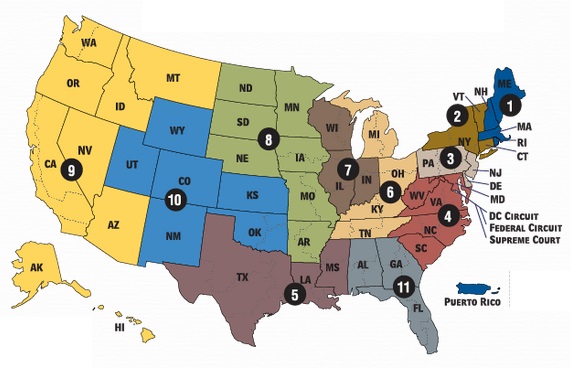

As you probably know, given that it’s pretty much all I talk about these days, I’ve been researching Supreme Court cases involving issues of church-state separation in relation to public education. My hope is to have something ready before the entire system collapses and any benefit one may derive from it is no longer relevant.

Given the state of the 2020 elections as I post this, I’m probably way too late.

Given the state of the 2020 elections as I post this, I’m probably way too late.

Nevertheless, I’ve been wrong before. Democracy may cough and bleed its way through another generation or so in some form, in which case I may sell as many as eleven copies of this lil’ liber sui generis. A few people may even find it helpful, enlightening – or at least mildly diverting.

Who am I kidding with all the humility? So far, it’s bloody brilliant and everyone will want seven copies just to show off.

In the meantime, I thought I’d share three of the books I’ve been reading as I continue researching my own. While the cases I’m including aren’t exactly obscure or difficult to document (most reached the Supreme Court, after all), the issues involved are often less universal than most “landmark” cases. Plus, as the subject suggests, most involve religion on some level. That means that while my trademark wit and brilliance will no doubt still prove engaging – perhaps even illuminating – it’s nevertheless important I make a genuine effort to incorporate other points of view than my own and a wider array of interpretations and contextualization.

After all, just because someone doesn’t share the same political ideals or personal theology as myself doesn’t mean they don’t deserve consideration and respect as a potential buyer. It all spends the same, kids.

While you eagerly await my own contribution to the field, here are three titles you should seriously consider if you’re even remotely interested in church-state relations as they pertain to public education – or even if you just want to look impressive with your reading choices over the holidays.

Have a Little Faith: Religion, Democracy, and the American Public School (History and Philosophy of Education Series), Benjamin Justice & Colin Macleod (University of Chicago Press, 2016)

The lessons of philosophy and the lessons of history bring us to the same place: resolving religious controversies in public schools must proceed from an informed understanding of the role of public schools as legitimate sites of civic education, where children learn to become reasonable citizens of a religiously pluralistic society.

This rather bold little volume seeks to unravel the history, as well as the social and political dynamics, of public education’s rocky relationship with faith in the United States. While Justice and Macleod are clearly not fans of turning public dollars or control over to narrowly focused factions, neither are they seeking to exclude those voices from the conversation. As they write in the introduction:

{W}e think that public education can serve democracy by helping citizens to reason with one another respectfully and productively, and to understand the complex ways that different faith perspectives (including those that reject religion) inform the lives of citizens.

They structure their case in two ways. First, the book is divided into historical eras – the Founding Fathers as they wrestled with the mix of religion and public education, the 19th century, the “Era of Progress” (roughly the Second Industrial Revolution and the Progressive Era), the 1960s and thereafter, and sample issues from the 21st century. Within this structure, they expertly walk the reader through history, educational practices, religious evolution in the U.S., and the various ways in which these elements intersect, with a focus on what they call “legitimacy.”

A diverse citizenry, they argue, is more likely to support outcomes they believe have both procedural legitimacy (they’re the result of fair procedures and democratic processes, even if not everyone loves the results) and substantive legitimacy (they demonstrate a good faith effort to accommodate the many voices involved in the process, even those in the minority). A religious community might accept that there will be no formal prayer at high school graduation if the process leading to that decision is transparent and the reasoning behind it is consistent with their understanding of how society is supposed to work. The same decision made without clarity as to why or how, or expressed in a way which seems contradictory to their understanding of the system, is more likely to provoke outrage and overt resistance. (I’m oversimplifying, but that’s the general idea.)

In short, then, what Justice and Macleod want is for the debate to be more informed on all sides – resolved by local boards and communities more often than by district courts or D.C. They get there through the best summary I’ve ever read of the history of public education – locally or nationally – as a function of collective needs and individual values. Having taught American History for so many years, I felt like I already had a pretty good grasp on the general educational trends and shifting social dynamics of the past few centuries, but the authors manage to highlight specific movements and interest groups that helped complete some of the connections I’d previously overlooked, as well as numerous other bits and pieces of history and culture. All in all, it’s a fascinating zoom-in on the past two centuries.

Justice and Macleod largely maintain the tone of researchers and advocates for improvement without obviously partisan political agendas, but by default this means readers with specific crusades in mind won’t find much to back them up in these pages. Advocates for public education may find themselves challenged, but most will also find some foundational convictions and ideologies validated along the way – not by mindless recitation of platitudes, but through balanced elucidation of history and founding principles as understood by those who first wrote them down. Even readers interested in “education reform” or convinced we need to reclaim “government schools” from the clutches of atheism and anti-Americanism may find insight and clarity here – minus the sort of “red meat” of which many have grown fond.

All in all, there’s a LOT of history and insight and challenge packed in to a relatively short, easy-to-read text. The authors seem to think we have every reason to be hopeful and that we’re perfectly capable of doing better. I hope they’re right.

Holy Hullabaloos: A Road Trip to the Battlegrounds of the Church/State Wars, Jay Wexler (2009)

Wexler offers valuable insights and analyses with a natural, comfortable humor – making this a very readable, relatable book despite some legitimately thorny topics. While he borders on name-dropping along the way, this can be forgiven since in real life he is apparently actually kind of a big deal. In fact, it’s possible that it’s not name-dropping at all so much as my own personal jealousy at the list of folks whose apartments and workplaces he references as part of this exceptional travelogue.

It’s also really, really funny in all the most accessible and respectful ways. That may be part of my jealousy as well.

School Prayer: The Court, the Congress, and the First Amendment, Robert S. Alley (1994)

The first few chapters of Alley’s book are devoted to the history behind the precise wording of the First Amendment’s two “religion” clauses, with a natural focus on James Madison.

The rest of the work jumps to the 20th century, especially the latter half (after Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp in the early 1960s), and a series of Presidential efforts and Congressional machinations to more openly label the U.S. as proudly and historically Protestant – and a fairly orthodox flavor, at that. A handful of relevant Supreme Court cases are addressed, but primarily in terms of legislative reaction and the various discussions and factions involved in trying to find a path around the Court’s interpretations of the Establishment Clause.

It was often closer than one might think.

The book ends in the early 1990s, meaning many of the most important cases from a contemporaneous perspective hadn’t happened yet (Lee v. Weisman is the last case covered in the book; Santa Fe ISD v. Doe wasn’t until 2000). Nevertheless, this book is a surprisingly readable and engaging journey through one of the most foundational debates in American history and culture – what role should faith play in a nation claiming to offer freedom of religion but at the same time so clearly founded in some sort of vaguely Protestant (almost non-sectarian, but not quite) “American Christianity”?

The book is rational and researched, so it naturally leans a bit left. Nevertheless, like the Justice & Macleod book, it offers a fascinating overview of a specific issue in American history over time.

Conclusion

At the moment, the status of our nation, whatever values we’re going to claim moving forward, or the actual role and reliability of our Supreme Court is all up in the air. One of the common themes I’ve discovered among Trump supporters over the past few years is their unshakable faith that nothing the President says or does, Congress says or does, or the Supreme Court says or does, can actually damage the nation in any permanent way because… America! They genuinely believe we are supernaturally invulnerable to any violation of our laws, traditions, values, or institutions, as if there’s a distinct, concrete idea of “America” that doesn’t rely on anyone actually maintaining or believing anything to remain omnipotent and eternal.

I find this conviction completely bewildering.

Because of that, I’ve had trouble knowing whether there’s a point to even finishing the book, given how quickly the precedents and procedures therein are likely to become entirely irrelevant moving forward as we move into an age of Rule by Shut-Up-Snowflake-I’m-Making-$(#&-Up-Over-Here! I’m pushing ahead, however, largely because I’m not sure how long it will take for the system to actually collapse and because – full transparency – I don’t have any better ideas.

That means that you, my Eleven Faithful Followers, are probably stuck with at least another six months of me talking about this stuff, whether anyone other than me cares or not. Thanks for sticking around.

RELATED POST: A Moment Of Silence: Wallace v. Jaffree (1985)

RELATED POST: “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases (Promo & Supplementals)

If you’re interested in far more concise case summaries accompanied by pithy-but-97%-sociopolitically-fair-and-balanced insights, check out

If you’re interested in far more concise case summaries accompanied by pithy-but-97%-sociopolitically-fair-and-balanced insights, check out  In

In  I assume that goes with the gig and that judges don’t take this stuff personally, but I’d have used bad words and probably thrown my gavel through the wall.

I assume that goes with the gig and that judges don’t take this stuff personally, but I’d have used bad words and probably thrown my gavel through the wall. Whoa there, tiger – I thought this was school! No one wants you teaching my kids to think for themselves. That’s why they’ve got me! (OK, that’s not entirely fair. Even the fundamentalists agreed in theory that they wanted their kids to practice critical thinking and such. It’s just that it was supposed to always lead to the same, predetermined outcomes.)

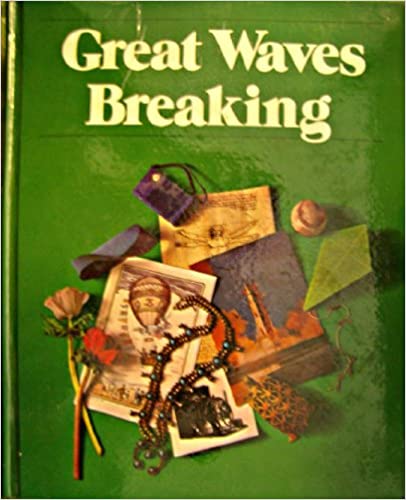

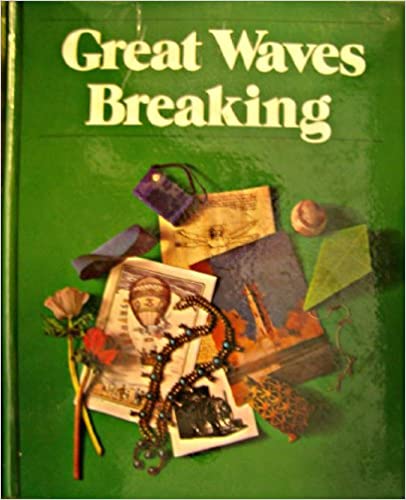

Whoa there, tiger – I thought this was school! No one wants you teaching my kids to think for themselves. That’s why they’ve got me! (OK, that’s not entirely fair. Even the fundamentalists agreed in theory that they wanted their kids to practice critical thinking and such. It’s just that it was supposed to always lead to the same, predetermined outcomes.) 200 hours is equivalent to five weeks of full-time employment doing nothing but finding things wrong with a middle school literature textbook. I actually have a copy of this reader (I tracked it down when I started reading about this case) and I’m not sure there’s 200 hours worth of analysis IN it. The average adult could read it cover to cover in a day, and none of the stories, plays, or poems are particularly complex.

200 hours is equivalent to five weeks of full-time employment doing nothing but finding things wrong with a middle school literature textbook. I actually have a copy of this reader (I tracked it down when I started reading about this case) and I’m not sure there’s 200 hours worth of analysis IN it. The average adult could read it cover to cover in a day, and none of the stories, plays, or poems are particularly complex. In her lengthy testimony Mrs. Frost identified passages from stories and poems used in the Holt series that fell into each category. Illustrative is her first category, futuristic supernaturalism, which she defined as teaching “Man As God.” Passages that she found offensive described Leonardo da Vinci as the human with a creative mind that “came closest to the divine touch.” Similarly, she felt that a passage entitled “Seeing Beneath the Surface” related to an occult theme, by describing the use of imagination as a vehicle for seeing things not discernible through our physical eyes.

In her lengthy testimony Mrs. Frost identified passages from stories and poems used in the Holt series that fell into each category. Illustrative is her first category, futuristic supernaturalism, which she defined as teaching “Man As God.” Passages that she found offensive described Leonardo da Vinci as the human with a creative mind that “came closest to the divine touch.” Similarly, she felt that a passage entitled “Seeing Beneath the Surface” related to an occult theme, by describing the use of imagination as a vehicle for seeing things not discernible through our physical eyes. Here’s where I confess I’m a bit confused. Not at Mrs. Frost – there are always a handful like her out there fighting principalities and powers and spiritual wickedness in children’s poems – but at the other parents and the legal team. There’s a case to be made that the textbook has a New Age-y, “One World” slant to it. But no reasonable adult can think they’re going to convince a federal judge that fostering imagination in children is essentially promoting the occult.

Here’s where I confess I’m a bit confused. Not at Mrs. Frost – there are always a handful like her out there fighting principalities and powers and spiritual wickedness in children’s poems – but at the other parents and the legal team. There’s a case to be made that the textbook has a New Age-y, “One World” slant to it. But no reasonable adult can think they’re going to convince a federal judge that fostering imagination in children is essentially promoting the occult. Or not.

Or not. Have you noticed that while the arguments made other parents or their lawyers are periodically referenced by way of context and summarizing the issues, every explanation as to why there’s no way they’re going to win this case starts with “Vicki First testified that…”?

Have you noticed that while the arguments made other parents or their lawyers are periodically referenced by way of context and summarizing the issues, every explanation as to why there’s no way they’re going to win this case starts with “Vicki First testified that…”? I lied, I will add one more comment. The court moves from why the three cases cited by the parents don’t apply to addressing the more general issue at the heart of this case – the role of public schools in serving society as a whole, not just select parts of it. Pierce Lively was as succinct and stirring as anyone on the highest bench had ever managed:

I lied, I will add one more comment. The court moves from why the three cases cited by the parents don’t apply to addressing the more general issue at the heart of this case – the role of public schools in serving society as a whole, not just select parts of it. Pierce Lively was as succinct and stirring as anyone on the highest bench had ever managed: Print this up and distribute it to every school board, judge, right wing talking head, or believer with a persecution complex. Think of how many problems we could solve if we had general understanding and agreement of this bit alone.

Print this up and distribute it to every school board, judge, right wing talking head, or believer with a persecution complex. Think of how many problems we could solve if we had general understanding and agreement of this bit alone.

While researching what I hope will be an upcoming book about the “wall of separation” as it relates to public education, I came across as case which has fascinated me far out of proportion to its actual importance. Since I try to keep the

While researching what I hope will be an upcoming book about the “wall of separation” as it relates to public education, I came across as case which has fascinated me far out of proportion to its actual importance. Since I try to keep the  Judge Hull opens with a basic summary of the case so far, then adds this intriguing commentary:

Judge Hull opens with a basic summary of the case so far, then adds this intriguing commentary: In 1944, the Supreme Court heard

In 1944, the Supreme Court heard  Second, “COBS”? Their self-selected group name was “COBS”? As in, things we say are up someone’s @$$ when they’re being unreasonably rigid or demanding in their beliefs? It’s not even a great group name spelled out – “Citizens Organized for Better Schools”? Was “Families Asserting Sincere Classroom Involvement Since Textbooks Suck” already taken?

Second, “COBS”? Their self-selected group name was “COBS”? As in, things we say are up someone’s @$$ when they’re being unreasonably rigid or demanding in their beliefs? It’s not even a great group name spelled out – “Citizens Organized for Better Schools”? Was “Families Asserting Sincere Classroom Involvement Since Textbooks Suck” already taken? That’s true inasmuch as judging the belief itself. The government has no business worrying about the validity of specific convictions or doctrines. That doesn’t mean the rest of society has to cooperate with such beliefs, however.

That’s true inasmuch as judging the belief itself. The government has no business worrying about the validity of specific convictions or doctrines. That doesn’t mean the rest of society has to cooperate with such beliefs, however. Most teachers aren’t interested in openly opposing parents or anyone else. We’re just trying to teach a little history or math or whatever. But most of us also won’t go out of our way to add to a kids’ problems if we can avoid it. I realize it drives conservatives crazy to hear this, but at times your suspicions are correct – there are those of us periodically trying to figure out a legal, non-fireable way to do what’s best for your kids. There’s often an unpleasant dissonance, however, between what’s desperately needed by that young person in front of us with no one else to turn to and what’s dictated by cover-your-ass policies. I can shift the conversation back to those multiple choice questions they missed or write them a pass to the school counselor who doesn’t know them from Salvatore Perrone and have a much better chance of keeping my job, but I’ll probably go to Teacher Hell by way of tradeoff.

Most teachers aren’t interested in openly opposing parents or anyone else. We’re just trying to teach a little history or math or whatever. But most of us also won’t go out of our way to add to a kids’ problems if we can avoid it. I realize it drives conservatives crazy to hear this, but at times your suspicions are correct – there are those of us periodically trying to figure out a legal, non-fireable way to do what’s best for your kids. There’s often an unpleasant dissonance, however, between what’s desperately needed by that young person in front of us with no one else to turn to and what’s dictated by cover-your-ass policies. I can shift the conversation back to those multiple choice questions they missed or write them a pass to the school counselor who doesn’t know them from Salvatore Perrone and have a much better chance of keeping my job, but I’ll probably go to Teacher Hell by way of tradeoff. The danger in bending over backwards to accommodate parents or students is that once you’ve established that precedent, there’s no telling what you’ll be expected to do moving forward. Worse, teachers and administrators sound like complete tools whenever they express this up front.

The danger in bending over backwards to accommodate parents or students is that once you’ve established that precedent, there’s no telling what you’ll be expected to do moving forward. Worse, teachers and administrators sound like complete tools whenever they express this up front.

This is an important distinction. The parents weren’t trying to get their own materials or beliefs injected INTO the curriculum; they were merely trying to allow their own children to opt OUT of the existing materials because they found them offensive. This sets the issue apart from issues like school prayer or creationism, in that they’re not apparently interested in pressuring other children into conforming to their religious druthers. If there were, the case would be far simpler. It might even have justified the way the judge in Tennessee completely blew them off and no-wonder-he’ll-never-reach-the-circuit-courts-like-us.

This is an important distinction. The parents weren’t trying to get their own materials or beliefs injected INTO the curriculum; they were merely trying to allow their own children to opt OUT of the existing materials because they found them offensive. This sets the issue apart from issues like school prayer or creationism, in that they’re not apparently interested in pressuring other children into conforming to their religious druthers. If there were, the case would be far simpler. It might even have justified the way the judge in Tennessee completely blew them off and no-wonder-he’ll-never-reach-the-circuit-courts-like-us. Judge Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee would do just that. As instructed, he’d give the fundamentalists a fuller hearing and – hold on to your powdered wigs – decide that maybe they had a point after all. The first time through, he’d found that because the textbook and the school were entirely neutral towards religion in general or specific religions in particular, there was no First Amendment violation. The second time around (fresh from his scolding by the 6th Circuit), Hull found in favor of the parents and even fined the school district to pay for their legal expenses.

Judge Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee would do just that. As instructed, he’d give the fundamentalists a fuller hearing and – hold on to your powdered wigs – decide that maybe they had a point after all. The first time through, he’d found that because the textbook and the school were entirely neutral towards religion in general or specific religions in particular, there was no First Amendment violation. The second time around (fresh from his scolding by the 6th Circuit), Hull found in favor of the parents and even fined the school district to pay for their legal expenses.

I’ve been researching and drafting what I hope will be the next “Have To” History book. The focus is on the tricky balance between “free exercise” and “establishment” in relation to public education – how to allow students (and to a lesser extent, educators) to express their sincerely held beliefs while still protecting the supposed neutrality of the system towards all things supernatural. It’s fascinating stuff (well, to me, at least), but I confess I’m having trouble with potential titles.

I’ve been researching and drafting what I hope will be the next “Have To” History book. The focus is on the tricky balance between “free exercise” and “establishment” in relation to public education – how to allow students (and to a lesser extent, educators) to express their sincerely held beliefs while still protecting the supposed neutrality of the system towards all things supernatural. It’s fascinating stuff (well, to me, at least), but I confess I’m having trouble with potential titles. Enter Vicki Frost, the mother of several children attending public school in Hawkins County, Tennessee. School had only been a session for a few weeks in the Fall of 1983 when her 6th grade daughter brought home an English textbook containing a story she’d been assigned to read. This story, as it turned out, involved… mental telepathy. Worse, this fictional telepathy was treated by the story as if it were no big deal, despite clearly being un-Biblical.

Enter Vicki Frost, the mother of several children attending public school in Hawkins County, Tennessee. School had only been a session for a few weeks in the Fall of 1983 when her 6th grade daughter brought home an English textbook containing a story she’d been assigned to read. This story, as it turned out, involved… mental telepathy. Worse, this fictional telepathy was treated by the story as if it were no big deal, despite clearly being un-Biblical. District Judge Thomas Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (where the case presumably began) was not initially swayed by the parents’ complaints. He issued a summary judgement dismissing the case – meaning he didn’t find enough substance to their complaint to even hold a full trial. It’s sort of the judicial version of snorting and then asking, “Oh, were you serious?”

District Judge Thomas Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (where the case presumably began) was not initially swayed by the parents’ complaints. He issued a summary judgement dismissing the case – meaning he didn’t find enough substance to their complaint to even hold a full trial. It’s sort of the judicial version of snorting and then asking, “Oh, were you serious?” I’d respectfully suggest, however, that Frost and company made a major strategic error when they included their next example on the “naughty” list. Still quoting Judge Hull:

I’d respectfully suggest, however, that Frost and company made a major strategic error when they included their next example on the “naughty” list. Still quoting Judge Hull: