NOTE: This is an excerpt from “Have To” History: A Wall of Education.

Three Big Things:

1. To bring a case before any court, one must first establish “standing.” Typically this means proving specific individual harm resulting from the actions of another and demonstrating that the offending party has the power to change whatever’s causing the harm.

2. Being a taxpayer is rarely sufficient to prove standing in the courts to complain about how one’s tax dollars are being used, even if that use is clearly unconstitutional.

3. According to Flast v. Cohen, when it comes to violations of the Establishment Clause, however, unwanted exposure to the offense can be sufficient to show standing in the eyes of the law… because establishment isn’t like anything else.

Standing Before the Court

During the same session which determined in Board of Education v. Allen that states could provide textbooks to public and private schools alike without violating the Establishment Clause, even if many of those private school students were attending religious institutions, the Court announced in Flast v. Cohen that taxpayers had the right to oppose their tax dollars being used to do just that.

This was new. Sort of. But maybe not. It was also sort of confusing.

The case began when Florence Flast and other New York taxpayers objected to federal legislation which provided funds for the purchase of secular textbooks for use in religious private schools. They argued that using their tax dollars in this way violated the Establishment Clause. The government responded with a derisive chuckle and a gaze full of pity for these poor fools who clearly didn’t understand how these things worked.

See, way back in Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Mellon (1923), the Court had specifically addressed the question of whether or not taxpayers had standing to sue based on being taxpayers. “No,” they said. “Absolutely not. Don’t be stupid.” If the government takes your money against your will and then uses it for something you don’t like – especially something you’re pretty sure they’re not supposed to be doing anyway – take it up with your elected representatives. That’s totally not the job of the judicial branch – “separation of powers” and all that.

Besides, both the gathering of taxes and the distribution of state funds were simply too general and, you know… big. It was impossible to connect specific state expenses to individual taxpayer contributions in more than a theoretical way – like identifying which raindrops were responsible for a flood downriver weeks later. Besides, every act of legislation, particularly when it involves spending, potentially impacts the economy. Maybe the very act you’re opposing is actually lowering your taxes somehow – did you think of that, Little Miss Lawsuit-Pants?

Honey, Have You Seen My Precedent?

This reasoning remained largely unchallenged for several decades, at least directly. In a few cases involving church-state issues in relation to public education, however, it’s more like it was pragmatically ignored.

Everson v. Board (1947) was initiated by a taxpayer who didn’t like state funds being used to pay bus fare to religious schools. The Court ruled against him, but not for lack of standing. Neither the majority opinion nor Justice Robert Jackson’s dissent questioned the plaintiff’s right to bring the complaint; the case was determined entirely on grander constitutional grounds.

The plaintiffs in McCollum v. Board (1948) were parents of children in the district, but also filed as taxpayers who didn’t want their money used to support “released time” programs for religious instruction during the school day. Justice Robert Jackson’s concurrence addressed the issue of taxpayer concerns, finding that the cost of the program was negligible (unlike the bus fare issue in Everson). What he did not suggest was that taxpayer status itself was insufficient to bring the suit to begin with. The majority opinion itself focused on compulsory education laws and the role of parents as advocates for their children. Taxpayer status was simply not a factor.

A few years later in Zorach v. Clauson (1952), parents who opposed “released time” programs during the school day (but not actually on school grounds) claimed standing both as parents and taxpayers. Nothing in the record indicates anyone challenged this, and no one even mentioned Mellon.

Just to keep everyone on their toes, however, that same year, in Doremus v. Board of Education (1952), the Court shot down plaintiffs opposed to a New Jersey law mandating that Bible verses from the Old Testament be read to students at the beginning of each school day. One had filed suit as a parent, but the child in question didn’t seem sufficiently traumatized to establish “injury,” and by the time the case reached the Supreme Court, they’d graduated anyway – rendering that parent’s complaint moot in the eyes of the Court. The other had filed as a taxpayer, which the Court declared insufficient to establish standing.

Unlike in Everson, there was no specific legislative outlay of funds in Doremus for a taxpayer to challenge. Daily Bible-reading didn’t actually cost anything extra; school budgets stayed pretty much the same whether they pushed Old Testament theology on students or not. With no qualified plaintiff, the Court saw no need to rule on grander constitutional questions. (Dissenters argued that schools using their limited time and resources to promote faith instead of, say… math or reading was in fact of interest to taxpayers, but the majority was not convinced. The Supremes have rarely proven sympathetic towards Rune Goldberg arguments – it looks for immediate cause and effect whenever possible, and “coulda been studying the demise of the Whigs instead” simply wasn’t compelling.)

It Followed Her To School One Day (Which Was Against The Rules)

In the early 1960s, the Court struck down several varieties of state-sponsored prayer and Bible-reading in public schools. In Engel v. Vitale (1962), Abington v. Schempp (1963), and Chamberlin v. Dade County Board of Public Instruction (1964), the plaintiffs were each time parents of school-aged children who objected to this particular mixture of church and state. Their status as taxpayers was periodically referenced in records, but never as the crux of their standing before the courts.

What did emerge, however, in the Supreme Court’s Engel decision (and quoted in Abington the following year) was a critical distinction in how the twin religion clauses of the First Amendment should be approached:

Although these two clauses may, in certain instances, overlap, they forbid two quite different kinds of governmental encroachment upon religious freedom. The Establishment Clause, unlike the Free Exercise Clause, does not depend upon any showing of direct governmental compulsion and is violated by the enactment of laws which establish an official religion whether those laws operate directly to coerce non-observing individuals or not…

When the power, prestige and financial support of government is placed behind a particular religious belief, the indirect coercive pressure upon religious minorities to conform to the prevailing officially approved religion is plain. But the purposes underlying the Establishment Clause go much further than that. Its first and most immediate purpose rested on the belief that a union of government and religion tends to destroy government and to degrade religion…

The Establishment Clause thus stands as an expression of principle on the part of the Founders of our Constitution that religion is too personal, too sacred, too holy, to permit its “unhallowed perversion” by a civil magistrate.

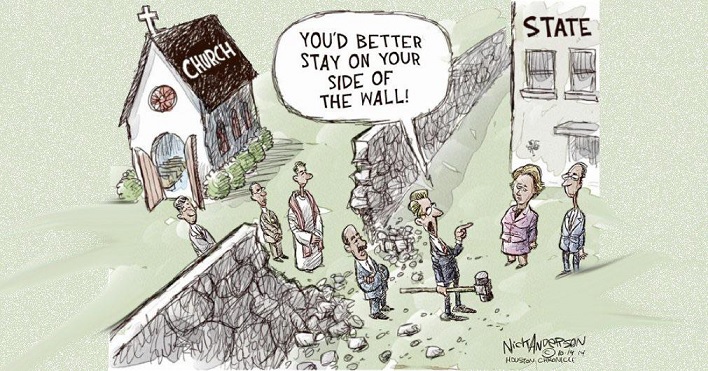

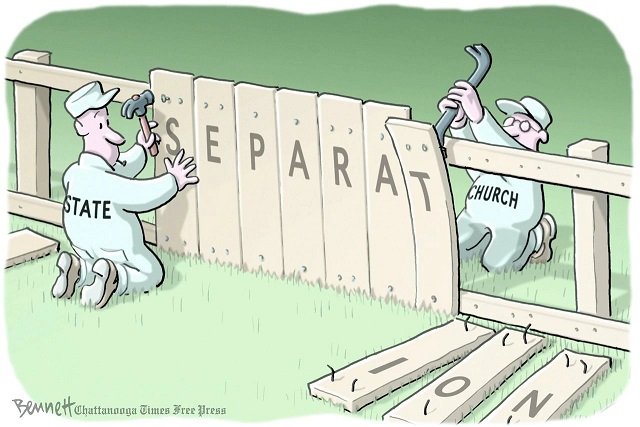

The twin religion clauses are often portrayed as pulling against one another, but Justice Black insisted, rather, that they in fact operate on two entirely different levels. “Free Exercise” constrains what the government can do that might interfere with sincerely held beliefs. It’s intended to allow personal pursuit of the divine as long as the general good is not overly compromised. It’s pragmatic and statutory. “Establishment,” on the other hand, is grander and more idealistic. It proclaims a principled division between the secular and the divine – between man’s laws and the whispers of the spirit. In so doing, it protects both.

Government sacrifices credibility the moment it dabbles in religious messaging, thus elevating some of its citizens over others and eroding the social contract. And while religion can benefit immensely from government sponsorship, true faith rarely survives it.

Or so the Court has repeatedly suggested, at least until recently.

What does this have to do with taxpayer standing in the courts? Everything. Establishment is the very first protection of the entire Bill of Rights, as well it should be. At the same time, it’s not quite like the other protections. More than free speech, a free press, freedom of assembly, or the right to petition for a new dress – more, even, than the free exercise of religion, the Establishment Clause seeks a grander right than those guaranteed to one citizen at a time. It claims for American citizens the right to render unto Caesar only the things that are Caesar’s and render unto God the things that are truly God’s – whatever those might be – without input or influence from secular authority.

Governmental violations of such a thing, then, don’t always work the same as other forms of state intrusion or overreach. They may even arrive as angels of light – generalized benefits disproportionately assisting religious institutions, rituals meant to acknowledge the dominance of some faiths over others, or public displays reinforcing the majority culture at the expense of those on the outside looking in. What makes Flast such an odd little outlier of a case is the Court’s stretch to recognize and accommodate this difference in objective, legal terms.

Flast v. Cohen (1968)

In Flast, a group of taxpayers objected to the use of public funds to provide secular textbooks for sectarian schools. The government argued that based on established precedent, they had no right to sue. The case, then, became about standing rather than the merits of their complaint. If they weren’t qualified to bring the suit to begin with, it didn’t really matter how right or wrong they were on substance.

The Supreme Court determined that there was nothing in the Constitution barring federal taxpayers from challenging taxing and spending they believed to be unconstitutional, so long as they could persuasively demonstrate a “necessary stake” in the results. Plaintiffs had to demonstrate that a legislature had exceeded its constitutional authority for taxing and spending AND identify a specific constitutional right being violated in order to show actual “harm” being done to them in some way.

Here’s how Chief Justice Earl Warren put it in the Court’s majority opinion (internal quotes and citations have been omitted for clarity):

The fundamental aspect of standing is that it focuses on the party seeking to get his complaint before a federal court, and not on the issues he wishes to have adjudicated. The gist of the question of standing is whether the party seeking relief has alleged such a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy…

{W}e find no absolute bar in Article III to suits by federal taxpayers challenging allegedly unconstitutional federal taxing and spending programs…

First, the taxpayer must establish a logical link between that status and the type of legislative enactment attacked. Thus, a taxpayer will be a proper party to allege the unconstitutionality only of exercises of congressional power under the taxing and spending clause of Article. I, Section 8, of the Constitution… Secondly, the taxpayer must… show that the challenged enactment exceeds specific constitutional limitations imposed upon the exercise of the congressional taxing and spending power, and not simply that the enactment is generally beyond the powers delegated to Congress…

While we express no view at all on the merits of appellants’ claims in this case, their complaint contains sufficient allegations under the criteria we have outlined to give them standing to invoke a federal court’s jurisdiction for an adjudication on the merits.

In practice, this turned out to mean that only when the Establishment Clause was involved would being a taxpayer secure standing in the eyes of the law. The decision in Flast wasn’t quite that specific, but in the half-century since, that’s how it’s worked out.

The Lemon Aid

A few short years later, in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), the Court ruled against state support of religious education via materials and – in some cases – salary support, declaring it a constitutional no-no. The plaintiffs were taxpayers in the relevant districts and several also had children in the local schools, so standing wasn’t an issue. The aid was a bit more involved, making it different from mere “textbooks” in the eyes of the Court. From Lemon emerged the “Lemon Test,” an informal tool often utilized by the Court to weigh the church-state constitutionality of government actions. The Lemon Test has three parts:

First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion… finally, the statute must not foster “an excessive government entanglement with religion” …

Those first two would come up more often than the third, and later evolve into what’s commonly referred to as the “endorsement test.” While not official (and recently all but officially overturned), the Lemon Test acknowledges the importance of how government actions are perceived as well as their intent. In other words, establishment is not just about the letter of a law – it’s about motivations and practical results as well.

“Unwanted Exposure”

Sometimes, of course, Establishment Clause violations come without obvious taxing and spending involved, meaning they don’t trigger the standing requirements outlined in Flast. In these cases, the Court will often allow plaintiff standing based on what Professor Carl H. Esbeck of the University of Missouri School of Law calls “unwanted exposure.” In practice, this means that even if someone’s tax dollars aren’t directly paying for something, that doesn’t mean it’s OK for the government to push a message approving some faiths over others, or faith in general over no faith at all. Violations of the Establishment Clause don’t have to be expensive to be violations.

In Stone v. Graham (1980), the Court invalidated a Kentucky state law which required public schools to post the Ten Commandments in classrooms. The actual copies of the Decalogue were donated by outside organizations, so there was no legislative spending involved. As with the mandatory prayer or Bible-reading in Engel or Abington, however, students were still exposed to a daily religious message brought to them on behalf of their government and with subtle but unpleasant consequences for those who chose not to play along. The plaintiffs in Stone, several parents and one teacher, had standing based on this “unwanted exposure” not covered in Flast.

In Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Inc. (1982), the Court refused standing to taxpayers who complained about the transfer of government property to a Christian college. The decision had been made by the Executive Branch; there was no legislation instituting new taxes or creating new spending involved. The Court based its reasoning on the two-part test established in Flast.

Marsh v. Chambers (1983) originated with a Nebraska state legislator who didn’t like paying local clergy to offer a prayer at the beginning of each day. The government didn’t make standing a major issue, but the Supreme Court’s majority opinion acknowledged in a footnote that “we agree that Chambers, as a member of the legislature and as a taxpayer whose taxes are used to fund the chaplaincy, has standing to assert this claim.” In short, he had standing based on both taxpayer status and “unwanted exposure.” (Chambers lost his case on its merits, however, based largely on the idea that adults aren’t children forced to do what others tell them to all day. “Legislators, federal and state, are mature adults who may presumably absent themselves from such public and ceremonial exercises without incurring any penalty, direct or indirect.”)

Lynch v. Donnelly (1984) – The Message Conveyed

Lynch v. Donnelly challenged the constitutionality of a Christmas display put up by the city of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, each year which prominently featured a full Nativity Scene (Mary, Joseph, a glowing Baby Jesus, etc.) The Court did not address standing as such, but the plaintiffs were local residents who would have easily qualified under the “unwanted exposure” principle inherent in the Court’s previous decisions. In terms of its impact on cases related to education, the real significance of Lynch was captured in the concurring opinion of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor:

The Establishment Clause prohibits government from making adherence to a religion relevant in any way to a person’s standing in the political community. Government can run afoul of that prohibition in two principal ways. One is excessive entanglement with religious institutions, which may interfere with the independence of the institutions, give the institutions access to government or governmental powers not fully shared by non-adherents of the religion, and foster the creation of political constituencies defined along religious lines…

The second and more direct infringement is government endorsement or disapproval of religion. Endorsement sends a message to non-adherents that they are outsiders, not full members of the political community, and an accompanying message to adherents that they are insiders, favored members of the political community. Disapproval sends the opposite message…

The meaning of a statement to its audience depends both on the intention of the speaker and on the “objective” meaning of the statement in the community. Some listeners need not rely solely on the words themselves in discerning the speaker’s intent: they can judge the intent by, for example, examining the context of the statement or asking questions of the speaker. Other listeners do not have or will not seek access to such evidence of intent. They will rely instead on the words themselves; for them, the message actually conveyed may be something not actually intended. If the audience is large, as it always is when government “speaks” by word or deed, some portion of the audience will inevitably receive a message determined by the “objective” content of the statement, and some portion will inevitably receive the intended message. Examination of both the subjective and the objective components of the message communicated by a government action is therefore necessary to determine whether the action carries a forbidden meaning.

Although Justice O’Connor doesn’t explicitly connect the two, this is why “unwanted exposure” was (and is) a valid foundation for standing. It doesn’t mean the individual will win every time they complain (the Court said Pawtucket could keep its Nativity Scene, for example), but it does recognize that violations of the Establishment Clause aren’t always full of obvious arm-twisting or overt threats to “non-adherents.” There’s more to many government messages than the literal, face-value words or actions. Just like your kids, teachers, co-workers, boss, or spouse, sometimes you know quite well what’s being communicated even if the other person doesn’t come right out and say it.

Also coming before the Court in 1984 was the case of Allen v. Wright, in which some very messy issues regarding racial segregation and the ugly history of private schooling across the south. In Allen, a conglomeration of Black parents argued that tax-exempt status for segregated private schools and tax deductions for those who supported them were unconstitutional based on the Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) a generation before and numerous acts of the federal government since. They were rejected for lack of standing.

Turns out the issue still wasn’t as clear cut as Flast or subsequent decisions had presumably tried to make it.

Stomping Decisis (Introduction)

Stomping Decisis (Introduction)

A few days ago, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Carson v. Makin, a case involving state support of religious education in rural Maine. The short version is that states which offer any sort of support for private schooling or alternatives to state-run public schools cannot deny equivalent support to religious institutions claiming a comparable role. These institutions need not follow state curriculums or abstain from indoctrination. They may pick and choose their students on any basis they like and may teach what they like, however they like, and still get paid by the state for each student they choose to accept.

A few days ago, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Carson v. Makin, a case involving state support of religious education in rural Maine. The short version is that states which offer any sort of support for private schooling or alternatives to state-run public schools cannot deny equivalent support to religious institutions claiming a comparable role. These institutions need not follow state curriculums or abstain from indoctrination. They may pick and choose their students on any basis they like and may teach what they like, however they like, and still get paid by the state for each student they choose to accept. Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.

Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.