I came across this piece via Claudia Swisher, who shared it as a link in a recent post about school vouchers. I found it both enlightening and provocative, and hoped by sharing it here as a blog post rather than an attachment, it might receive even wider readership than it has deservedly earned already.

I’d like to thank Edd Doerr for his gracious permission to repost it here. I’ve made minor formatting changes for readability, and omitted his list of resources at the end. You can read or download the original at Americans for Religious Liberty.

THE GREAT SCHOOL VOUCHER FRAUD (July 2012)

Edd Doerr, President, Americans for Religious Liberty

Introduction

Should government(s) compel taxpayers to support religion-based and other private schools? This question has vexed the United States—and such other countries as Great Britain, Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, the Netherlands, and France—for over two centuries. Controversies over this question extend back to the beginning of the American republic but have been intensifying over the past half century, reaching crisis proportions since the elections of 2010.

In 2011, Indiana’s Republican legislature and governor passed a school voucher bill more expansive than anything previously adopted by any state. In 2012 Louisiana’s Republican dominated legislature and governor passed the most radical, far-reaching plan for public funding of religion-based and other private schools in our history. In November of 2012 Florida voters will be asked to decide in a referendum to approve an amendment to the state constitution to allow tax aid to church-based schools. In May of 2012 presidential candidate Mitt Romney expressed support for school vouchers.

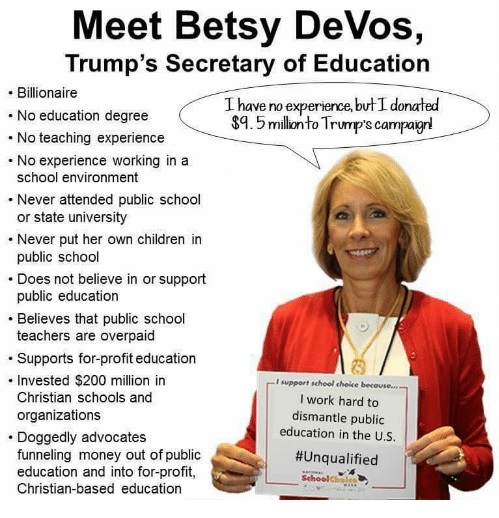

Combined with this drive to provide public funding for religious and other private schools has been an unprecedented tsunami of assaults on the public schools serving 90% of our K-12 students. These assaults involve wholesale slashing of public school budgets, layoffs of teachers and other school personnel, increases of class sizes, elimination of instructional and other programs, intense propaganda campaigns against teachers and teacher unions, and attacks on the very idea of religiously-neutral, democratic public education.

Together, this two-front war on religious freedom and public education constitutes nothing short of a major national crisis.

This position paper will show how these crises are among the most serious in our history, and how they could have profound, perhaps irreversible effects on our future. It will argue that We the People have both the power and the duty to end the threats to our most important principles and institutions.

This paper will place the school voucher and related issues in historical perspective and show that all plans and programs for diverting public funds to religion-based and other private schools are inimical to the vital interests of the overwhelming majority of Americans.

But first, definitions: School vouchers are payments from public treasuries—federal, state or local—to cover all or part of the tuition and other costs at private schools, about 90% of which are church-related and generally “pervasively sectarian.” Voucher plans exist in almost infinite variety. They may, for example, be keyed to family income. Important variants of voucher plans are tuition tax-credit plans (sometimes referred to as “tax-code vouchers”), involving full or limited tax credits for parents or corporations or other entities that pay for tuition at nonpublic schools. (See Stephanie Saul’s article, “Public Money Finds Back Door to Private Schools,” New York Times, May 22, 2012.) Other plans for channeling public funds have included bus transportation, textbook loans, audio-visual equipment, and part-time utilization of public schools (so-called “shared time”).

Background

Beginning in 1607 a diverse collection of people began settling the eastern coast of North America. They came from England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Africa (under duress) and elsewhere. Among them were Anglicans, Congregationalists (Puritans and Pilgrims), Roman Catholics, Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Jews, Quakers, Mennonites, Dutch Reformed. Many came for greater religious freedom, although most of the colonies they set up practiced varying degrees of intolerance toward dissenters and generally compelled tax support for religion.

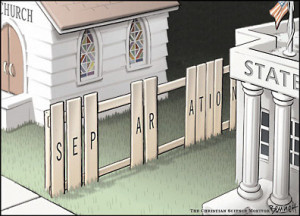

From humble beginnings these disparate people evolved the most advanced, free nation in the world. And central to this process was the development of a nonsectarian public school system and the generally accepted constitutional principle of separation of church and state, of religion and government.

The separation principle, though articulated in the early seventeenth century by Roger Williams, had to wait for Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and other Virginians to be implemented. In the same year that the Declaration of Independence was signed, the Virginia legislature voted to dis-establish the Anglican Church and expand religious freedom. Since these steps did not go far enough, Jefferson, Madison, and Baptist and Presbyterian leaders began a drive to completely separate church and state. Their efforts led to the passage in 1786 of Jefferson’s Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom. This Act ended legal compulsion to attend church services and barred tax support for religious institutions. It provide that “no man… shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burdened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or beliefs, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge or affect their civil capacities.”

By the time the First Amendment to the Constitution was adopted in 1791, all the states guaranteed religious liberty to a large degree and only four retained substantial vestiges of religious establishments. As Leo Pfeffer has pointed out, the movement toward separation of church and state began with gradual extensions of religious liberty, then saw single establishments give way to multiple establishments, and ended with the cessation of all tax aid for religious institutions. Pfeffer adds:

“It is important to note that in no case did the development end until complete disestablishment was arrived at: no state stopped with according freedom of worship, or indeed with less than complete prohibition of tax support of any and all religions. Moreover, every state that entered the union after the Constitution was adopted incorporated both prohibitions in the constitution or basic laws. In no case was there any attempt to establish any denomination or religion; on the contrary, in varying language but with a single spirit, all states expressly forbade such attempt. This deliberate decision was not motivated by indifference to religion: most of the states had been settled by deeply religious pioneers. Nor was it dictated by purely practical considerations; many of the states had a population far more homogenous religiously than Canada, Holland, or even England… The decision was in all cases voluntary; and it was made because the unitary principle of separation and freedom was as integral a part of American democracy as republicanism, representative government, and freedom of expression.”

Not only did the first thirteen states all follow the example set by Virginia and the First Amendment, but from 1876 on all new states added to the Union were required by Congress to include in their basic laws an irreversible ordinance guaranteeing religious freedom in line with the First Amendment. The constitutions of the two most recent states added to the Union after World War II, Alaska and Hawaii, both contain strong provisions prohibiting diversion of public funds to religious institutions. We might also note that when Congress considered and approved the constitution for the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico after World War II, that charter not only reiterated the “no establishment” and “free exercise” clauses of the First Amendment but also included the stipulation that “There shall be complete separation of church and state.” Church-state separation is an integral part of our heritage, not some minor footnote to history dismissed lightly by today’s Religious Right.

While the Constitution drafted in 1787 did not grant the federal government power to deal with religion in any way, it proscribed religious tests for public office, and provided for an affirmation instead of an oath of office. The absence of a specific religious freedom guarantee bothered Jefferson and others. Six states ratified the Constitution but insisted on a religious freedom amendment. Rhode Island and North Carolina declined to ratify it until a bill of rights was adopted.

Shortly after his election to the House of Representatives Madison introduced a compilation of proposals for a bill of rights to be added. Several versions of a religious liberty provision were considered before the following wording of what is now the First Amendment was adopted: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

President Jefferson, in a carefully thought-out 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, declared that these words built a “wall of separation between church and state.” Supporters of church-state separation hold that the “no establishment” clause was noted by the Supreme Court as early as 1878, but was best and most succinctly interpreted by the Supreme Court in the 1947 Everson v. Board of Education ruling. The Court stated:

“The ‘establishment of religion’ clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or non-attendance. No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion. Neither a state nor the Federal government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups and vice versa. In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between church and state’.”

Some conservatives have asserted that the “no establishment” clause was intended to prevent the setting up of a single established or preferred church, but most authorities have agreed with Leo Pfeffer that the Everson interpretation is correct.

The American Public School

While it would be impossible to do justice to the complex history of public education in America in this paper, a brief capsule treatment is necessary to put into perspective the current wave of assaults on public education and church-state separation.

During the colonial period American education was almost entirely a religious and private matter. In Puritan New England education was quasi-religious, quasi-public. In the middle colonies, with their greater religious diversity, church-related schooling was the rule. In the Anglican South what formal education there was was mainly private. As religious tolerance and pluralism grew, the church gradually faded from the New England educational scene and the community-controlled public school evolved, setting the pattern for the rest of the country. Following the political and economic upheavals of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, church-related and private education diminished as true public schools grew and proliferated.

Early nineteenth century public schools tended to be somewhat religious in orientation. But Horace Mann and other leaders successfully struggled to move the schools to a position of nondenominationalism, at least with regard to most Protestant denominations. Protestant Bible reading and prayers, which discriminated against the growing numbers of Catholic and Jewish children, were common and were generally upheld by the state courts. Catholic children were sometimes punished or expelled from schools for refusing to participate in essentially Protestant exercises.

Catholic parochial schools developed largely in response to the generally Protestant slant of public schools in the mid-nineteenth century. By the early 1960s Catholic private schools in the United States enrolled as many as 5.5 million students, perhaps one-half the number of Catholic children of school age. However, between the mid-1960s and 2012 Catholic school K-12 enrollment declined to about two million students, a drop due to the sharp post-World War II drop-off in anti-Catholic prejudice, the election of a Catholic president in 1960, the liberalizing of the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council, and the negative Catholic reaction to the 1968 Vatican condemnation of contraception and the bishops’ unbendingly conservative positions on a number of key social issues.

As early as 1872 the Ohio Supreme Court held that school boards could exclude Bible reading. In 1910 the Illinois Supreme Court, in a case brought by Catholic parents, held that school-mandated or school-sponsored Bible reading was constitutionally prohibited religious instruction, even when dissenting children could opt out. An increasingly pluralistic population not only exerted pressure to move the schools closer and closer to religious neutrality but also insured that the courts would eventually have to settle the continuing disputes.

In 1948 the Supreme Court ruled in McCollum v. Board of Education that voluntary “released time” religious instruction held in public schools violated the First Amendment, although four years later in Zorach v. Clausen the Court would hold that such instruction held off public school premises was not prohibited. In 1962 the Court decided in Engel v. Vitale that recitation in public schools of a prayer formulated by the New York State Board of Regents violated the First Amendment, holding that “it is no part of the business of government to compose official prayers for any group of American people to recite as part of a religious program carried on by the government.” The following year the Court struck down state-mandated Bible reading and recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in Abington School District v. Schempp. Religious censorship of public school curricula was dealt a blow in 1968 when the Court voided an Arkansas law designed to prevent the exposure of students to the theory of evolution. This in turn was reinforced in 1987 when the Supreme Court voted 7-2 in Edwards v. Aguillard to strike down Louisiana’s “equal time for creationism in public schools” law.

The Supreme Court, in ruling unconstitutional religious instruction and devotional activities in public schools, was neither exhibiting hostility toward religion nor prohibiting public schools from dealing with religion in ways that do not violate the First Amendment. The court pointed out in Schempp, for example, that the Bible may be used as a reference work and that schools may offer teaching about religion objectively and neutrally, as distinguished from the teaching of religion.

All attempts to get Congress to approve proposed amendments to the Constitution to permit “voluntary” or “nondenominational” prayer in public schools have failed. Responsible religious leaders have opposed such amendments, recognizing that all students are free to pray privately in school. And the nation has no shortage of houses of worship.

Over the years, then, the American people have developed a comprehensive system of public schools about which Justice William Brennan could write in his concurring opinion in Schempp:

“The public schools are supported entirely, in most communities, by public funds—funds exacted not only from parents, nor from those who hold particular religious views, nor indeed from those who subscribe to any creed at all. It is implicit in the history and character of American public education that the public schools serve a uniquely public function: the training of American citizens in an atmosphere free of parochial, divisive, or separatist influence of any sort—an atmosphere in which children may assimilate a heritage common to all American groups and religions. This is a heritage neither theistic nor atheistic, but simply civic and patriotic.”

It is clear now that the pan-Protestant flavor of many of our schools disappeared after the school prayer and creationism rulings (though this development tended to upset Protestant fundamentalists). The vestiges of anti-Catholicism largely vanished with these rulings, the election of a Catholic president in 1960, and the liberalizing Second Vatican Council of 1962-65, and this was followed by the decline in Catholic private school enrollment from 5.5 million in 1965 to two million in 2012.

(There is one problem that might be mentioned in connection with the preceding, one detailed in Katherine Stewart’s book The Good News Club: The Christian Right’s Stealth Assault on America’s Children {Public Affairs Press, 2012}, which I reviewed in the April/May 2012 Free Inquiry under the head “Invasion of the Soul Snatchers.” Over the past decade fundamentalist Christian missionaries have been infiltrating public schools as a result of some sloppy court rulings. But that goes beyond our subject.)

International Comparisons

Some perspective on the school voucher controversy can be gained with a hasty overview.

Great Britain. The UK began tax subsidies for Church of England schools in 1833, to Catholic, Methodist and other schools by 1870. Only after 1870 did the UK set up what we Americans call public schools. (“Public” schools in the UK are private schools.)

Ireland. Virtually all schools are tax-supported church-related schools. In 2012, however, this may begin to change in reaction to the clergy sexual abuse scandals and coverups.Northern Ireland. Here we see a modified form of the UK system. Nearly all Catholic children attend tax-supported Catholic schools, while the public schools are understandably Protestant oriented.

Netherlands. Public education was well developed by 1860, when 79% of students attended public schools. Catholic and Reformed Church leaders waged a long campaign to obtain tax support. Their goal was achieved a century ago by pastor and prime minister Abraham Kuyper, a figure much admired by American religious ultraconservatives.

France. Beginning early in the twentieth century French education was public, free, compulsory, and secular. During World War II Petain’s collaborationist government permitted religious teachers to return to public schools and by the late 1950s the DeGaulle government had begun public subsidies for Catholic schools.

Canada. Practice varies by province in Canada. Ontario supports public and Catholic schools, thanks to the British North American Act of 1867, but not Protestant or Jewish schools. Newfoundland presents an interesting case. The province became part of Canada in 1949. It had no public schools, but five systems of church-related private schools. This was so unsatisfactory that the provincial government in the 1990s voted to replace the arrangement with religiously neutral public schools. Three-fourths of Newfoundland voters ratified the new arrangement at the polls.

Australia. After World War II politics down under saw extensive battles over religious freedom issues, ending with both federal and state tax aid to church-related private schools. Although Australia’s constitution contains an establishment clause copied from the U.S. First Amendment, the country’s highest court in the 1970s chose to ignore it in the case brought by the D.O.G.S. (Defense of Government Schools) organization. (American attorney Leo Pfeffer and I were involved in setting up the lawsuit.)

The Case Against School Vouchers

We are now ready to examine the very substantial case against school vouchers and similar plans. But first, we should take a look at the arguments for vouchers. They fly the banners of “choice,” “parental choice,” and “competition.”

The “choice” mantra is deceptive. It carefully avoids calling attention to the fact that it is the private school that chooses which children to admit, which teachers to hire using which criteria, which religion or ideology to promote, which children and teachers to exclude, which ideas to censor (such as evolution or climate change or reproductive choice).

The “choicers” deny choice, however, to taxpayers who do not wish to voluntarily or involuntarily support religious institutions, particularly those that target their own religious views as wrong or abhorrent.

As for competition, does anyone really believe that Catholic, Lutheran, Seventh-day Adventist, Baptist, Pentecostal, Jewish, Muslim, or other religion-related private schools compete for the same students?

As the case against school vouchers is multifaceted, this paper will break it down into several discrete arguments. As some readers will give more weight to some factors, these will not be prioritized.

Vouchers and Religious Freedom

About 90% of nonpublic schools are religion based: Catholic, Lutheran, Jewish, Adventist, Episcopal, Christian Reformed, “Christian,” Friends (Quakers), Muslim, and independent evangelical. These schools are not merely similar to public schools with a religion class tacked on; they tend to be pervasively religious. Selection of teachers, administrators, and textbooks is related to religious criteria. Religion-related schools promote sectarian teachings on such matters as reproductive choice, evolution, history and gay rights. While Catholic schools tend to use much the same books as public schools, Albert Menendez shows in his book Visions of Reality: What Fundamentalist Schools Teach (Prometheus, 1993) that this large segment of private schools uses textbooks so religiously slanted and wildly sectarian that they could never be adopted by public schools.

Compelling taxpayers to support religion-related private schools, directly or indirectly, is about as serious a violation of religious freedom as can be imagined. As James Madison noted in his majesterial 1785 Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, “It is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties,” and “Who does not see that the same authority which can… force a citizen to contribute three pence only of his property for the support of any one {religious} establishment, may force him to confirm to any other establishment in all cases whatsoever.”

Benjamin Franklin’s view was: “When a religion is good, I conceive it will support itself; and when it does not support itself, and God does not take care to support it so that its professors are obliged to call for the help of the civil power, ‘tis a sign, I apprehend, of its being a bad one.”

Forcing citizen-taxpayers to contribute directly or indirectly to private schools is tantamount to forcing a Catholic to support a Baptist school, a Jew to support a Muslim school, a Unitarian to support a fundamentalist school.

Vouchers and Public Opinion

By virtually every measure a strong majority of Americans across the political and religious spectra is opposed to school vouchers. For 40 years the annual Gallup/Phi Delta Kappa education polls have registered opposition to school vouchers. The most recent, in 2011, showed opposition at 65% to 34%.

Even more significant are the 27 statewide referendum elections over a 40-year span in which literally millions of Americans have voted directly on vouchers, tax code vouchers, amendments to state constitutions to allow tax aid to religion-related and other private schools, and lesser forms of aid. The 27 referenda are summarized in Figure 1.

Averaging these percentages shows opposition to tax aid for nonpublic schools at 63% to 36.5%. However, adjusting these votes to take into account the actual populations of the states involved shows opposition at 65.9% to 34.1%, almost exactly the same as the 2011 Gallup/PDK poll.

Further breaking down of these referendum votes shows opposition to vouchers at 66.5% to 33.5% in eight referenda and to tax code vouchers in five referenda at 68.6% to 31.4%. Combining the figures for vouchers and tax code vouchers shows opposition at 67.3% to 32.7% in 13 referenda. Opposition to amendments to state constitutions to allow tax aid for nonpublic schools in six states averaged 62.3% to 37.7%. The average for all 19 referenda is 65.7% to 34.3%.

Average opposition to relatively more minor forms of tax aid for nonpublic schools in eight referenda comes to 56.5% to 43.5%.

These referendum results clearly show that opposition to the two main types of vouchers and permissive constitutional change in 19 referenda is two to one, while opposition to minor or more peripheral forms of aid in eight referenda is slightly less.

Figure 1: The Statewide Referenda on School Vouchers or Their Variants, 1966-2007

Nebraska – 1966 Bus transportation: 57-43 against (%)

New York – 1967 Constitutional change to allow tax aid: 72-28 against

Nebraska – 1970 Tax code vouchers: 57-43 against

Michigan – 1970 Constitutional change to allow tax aid: 57-43 against

Oregon – 1972 Constitutional change to allow tax aid: 61-39 against

Idaho – 1972 Bus transportation: 57-43 against

Maryland – 1972 Vouchers: 55-45 against

Maryland – 1974 Auxiliary services: 56-43 against

Washington State – 1975 Constitutional change to allow tax aid: 60-39 against

Alaska – 1976 Constitutional change to allow tax aid: 54-46 against

Missouri – 1976 Auxiliary services: 60-40 against

Michigan – 1978 Vouchers: 74-26 against

Washington, DC – 1981 Tax code vouchers: 89-11 against

California – 1982 Textbook aid: 61-39 against

Massachusetts – 1982 Auxiliary services: 62-38 against

Massachusetts – 1986 Constitutional change to allow tax aid: 70-30 against

South Dakota – 1986 Textbooks: 54-46 for

Utah – 1988 Tax code vouchers: 70-30 against

Oregon – 1990 Tax code vouchers: 67-33 against

Colorado – 1992 Vouchers: 67-33 against

California – 1993 Vouchers: 70-30 against

Washington State – 1996 Vouchers: 64-36 against

Colorado – 1998 Tax code vouchers: 60-40 against

Michigan – 2000 Vouchers: 69-31 against

California – 2000 Vouchers: 71-29 against

South Dakota – 2004 Auxiliary services: 53-47 against

Utah – 2007 Vouchers: 62-38 against

Florida – 2012 Vouchers: 55-45 against

Hawaii – 2014 Vouchers: 55-45 against

While we are on the subject of public opinion, we might note that the annual Gallup/PDK polls ask respondents to give letter grades (A, B, C, D, F) to public schools. The results are similar each year, but just look at the most recent, in 2011. Gallup found that only 17% gave an A or B grade to public schools nationwide, 51% gave an A or B to schools in their community, but 79% gave an A or B to the public school attended by their oldest child. In other words, my child’s school is good, the other schools in town are so-so, and the schools nationally are awful. Put another way, the school known best is fine, but the rest of the schools are not so great, and the farther away they are, the worse they are.

What can this possibly mean? Just this: conservatives and conservative media tend not only to favor diversion of public funds to church-related and other private schools but also lose few opportunities to criticize public schools, teachers, and especially the teacher unions that protect the interests of the teaching profession, the schools, and the students. We are accustomed to hearing or reading such comments as these: “They kicked God out of the schools and let blacks in”; “Teachers are overpaid”; “Public schools teach evolution and other ‘secular humanist’ and ‘anti-Christian’ ideas.”

Interestingly, when Gallup asked respondents to rate teachers in their local schools, 69% gave a grade of A or B. But when asked to rate the parents of school children, only 36% gave an A or B.

Vouchers, Public Schools and Public Policy

Expansion of voucher and tax code voucher plans is inimical to religiously neutral democratic public education. The many reasons for opposing vouchers are displayed below. Each is valid by itself, but in the aggregate they make a devastatingly comprehensive case for opposing any and all school voucher plans, large or small, federal or state.

• Because of the pervasively sectarian nature of the 90% or so of nonpublic schools, voucher plans would fragment our school population along religious, ideological, class, ethnic, ability level and other lines. Think about it. Jewish parents are not going to send kids to Christian or Muslim schools. Catholic parents are not going to send theirs to Jewish or Protestant schools. Evangelicals are not going to send theirs to Catholic schools. Moderate to liberal parents will not send their kids to schools that denigrate women’s rights, reproductive choice, and evolution.

My 2000 book Catholic Schools: The Facts, based primarily on data from official Catholic school sources, paints a pretty good picture of the largest nonpublic school system. The data show that urban Catholic schools enroll only one-third the percentage of students in the lowest quartile of socioeconomic status as public schools, and twice as many in the highest quartile.

Voucher supporters sometimes make much of the fact that some urban Catholic schools have admitted black students to replace the white Catholic students whose families departed for the suburbs and send their kids to suburban public schools. However, complaints have been numerous that the urban Catholic schools try to convert Protestant children to Catholicism.

• Vouchers tend, for obvious mathematical reasons, to favor larger religious traditions over smaller ones. The flow of public funds to existing church-related schools would motivate other religious groups to get into the school business to get their “fair share” of the largesse. Expansion of private schools necessarily means shrinkage of public schools.

• The religious and ideological compartmentalization of education would lead to religious and ideological tests for hiring, firing and promoting teachers. Teaching would become an increasingly splintered and unattractive profession, especially as tenure, collective bargaining and unions are frowned on by nonpublic schools.

• Most religion-based private schools are unfriendly to women’s rights, reproductive choice, and LGBT rights and interests. Vouchers would deal these interests a severe blow.

• Most religion-based schools are hostile to the teaching of evolution and the science of climate change. Vouchers would thus weaken science literacy.

• Given the vast array of competing religions and ideologies, vouchers could only adversely affect economies of scale. Administrative costs would rise; staff compensation would shrink.

• About half of K-12 students require bus transportation. As public and nonpublic school attendance areas rarely coincide, as nonpublic schools serve more geographically-scattered constituencies, and as at present most nonpublic schools benefit from tax-supported school bus service, voucher-aided private school expansion would greatly increase school transportation needs and costs, further clogging our streets with big yellow school buses. We need not mention the increase in fossil fuel use.

• Someone is sure to say that private schools could not accommodate a huge influx of students with tax-paid vouchers. But the shrinking of public school enrollment would render some public school buildings superfluous. Local governments would likely find it expedient to sell off the unused buildings. Further, the drop in Catholic school enrollment from 5.5 million in 1965 to two million in 2012 leaves a lot of space for private school expansion. Then, too, there are 300,000 or so houses of worship in the United States with religious education facilities used only on Sunday mornings. If just 100,000 of these would each provide space for 200 students, ten million children could be accommodated in new private schools at minimal additional expense.

• Finally, as this paper was being readied for publication in mid-June, 2012, the U.S. Senate was faced with demands that the District of Columbia school voucher program, passed under the George W. Bush administration, be expanded. Let me quote from the letter to the Senate Committee on Appropriations submitted by 50 educational, religious, civil rights, civil liberties, and other member organizations of the National Committee for Public Education (NCPE) on June 14, 2012:

In addition to the many problems with the DC voucher program—including religious liberty and civil rights issues—it has proven ineffective. All four of the congressionally-mandated U.S. Department of Education (USED) studies that have analyzed the DC voucher program concluded that it did not significantly improve reading or math achievement, leaving no justification for continuing its funding. The USED studies further found that the voucher program had no effect on student satisfaction, motivation or engagement, or student views on school safety. The studies also indicated that many of the students in the voucher program were less likely to have access to key services such as ESL programs, learning supports, special education supports and services, and counselors than students who were not part of the program. Having failed to improve the academic achievement and school experience of the students in the program, the voucher program clearly does not warrant continued funding.

The Bottom Line

If you build it they will come. If public funds are available for private schools through vouchers or tax code vouchers, religious and other private interests will move into the education business. Children will be moved out of religiously and ideologically neutral democratic public schools responsible to elected school boards and subject to laws designed to protect the equal rights of students and staff.

Vouchers, if not stopped and rolled back, will ultimately destroy public education, weaken religious freedom, shred our American constitutional principle of separation of church and state, and negatively impact community harmony.

Voucher plans always start small, like pregnancies. Wisconsin’s plan applied at first two decades ago to private schools in one city, Milwaukee. Ohio’s plan started a bit later and was confined to Cleveland. The plans originally applied only to low income families, but the eligibility limit is incrementally moved upward. Some plans are limited—at first—to special needs children, but once a crack is allowed to appear in the church-state separation dike it is expanded to allow an increasing stream of money to flow to nonpublic schools. The goal is full public support of a growing multiplicity of religion-based and other special interest private schools along with the slow death by strangulation of public education.

Really? Yes, really. In 2011 Indiana’s legislature passed and Republican governor Mitch Daniels signed the most extensive voucher plan in the nation. In 2012 Louisiana outdid Indiana when its Republican legislature approved and Republican governor Bobby Jindal signed the most exhaustive legislation ever to pour taxpayers’ money into private schools through vouchers with relatively loose income-eligibility requirements, into expanded charter schools (a subject beyond the scope of this paper), accompanied by draconian attacks on public school teachers. Only days later Arizona’s Republican governor and legislature expanded eligibility for vouchers for private school tuition, tutoring, and a new fad that has so far been shown to be ineffective, on-line classes.

Vouchers and the Law

At this point, unfortunately, matters get complicated, unnecessarily so. Thirty-eight state constitutions prohibit the use of public funds for religious institutions, with greater or lesser degrees of clarity. (These provisions may be conveniently accessed in the book Religious Liberty and State Constitutions, Prometheus, 1993, edited by Albert Menendez and myself.) These provisions have proven to be a barrier to most attempts at the state level to divert public funds to nonpublic schools. Indeed, these barriers have led to five unsuccessful attempts to amend state constitutions and one successful campaign to strengthen a state constitution. Let’s take a quick look at these.

State constitutions can be amended in various ways—legislative approval or approval by two legislative sessions with an intervening election. All states but Delaware require that amendments be ratified in a voter referendum, which would require either a 50% or even 60% approval.

The first of these referenda was held in New York State on November 7, 1967. In 1966 advocates of tax aid to church schools succeeded in electing a majority of delegates to a state constitutional convention, which predictably voted to replace the strict church-state separation provision in the state charter, Article XI, Section 3: “Neither the state nor any subdivision thereof shall use its property or credit or any public money, or authorize or permit either to be used, directly or indirectly, in aid or maintenance, other than for examination or inspection, of any school or institution of learning wholly or in part under the control or direction of any religious denomination, or in which any denominational tenet or doctrine is taught, but the legislature may provide for the transportation of children to and from any school or institution of learning.” The campaign to ratify the change was intense. When the nearly five million votes in the November 7, 1967, referendum were counted, 72% of New York voters had upheld the anti-aid provision. (I was active in the referendum campaign as a member of the staff of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, which published my 186-page book on the affair, The Conspiracy That Failed, in 1968.)

The second referendum was held in Michigan in 1970. While the Michigan constitution already prohibited tax aid for church-related schools, lawmakers in Lansing kept trying to pass legislation to aid church-related schools. Exasperated, education leaders in the state decided to amend the constitution to strengthen what was already there. This involved drafting an amendment and petitioning it onto the ballot. (I helped write it and later traveled the state from Detroit to the Upper Peninsula to promote it.) After a hard-fought campaign voters approved the strengthening amendment by 57% to 43%. Here are the relevant sections of the Michigan constitution: “Article I, Section 4 … No person shall be compelled to attend, or against his consent, to contribute to the erection or support of any place of religious worship, or to pay tithes, taxes or other rates for the support of any minister of the gospel or teacher of religion. No money shall be appropriated or drawn from the treasury for the benefit of any religious sect or society, theological or religious seminary; nor shall property belonging to the state be appropriated for any such purpose … Article VIII, Section 2 … No public monies or property shall be appropriated or paid or any public credit utilized, by the legislature or any other political subdivision or agency of the state directly or indirectly to aid or maintain any private, denominational or other nonpublic pre-elementary, elementary, or secondary school. No payment, credit, tax benefit, exemption of deductions, tuition voucher, subsidy, grant or loan of public monies or property shall be provided, directly or indirectly, to support the attendance of any student or the employment of any person at any such nonpublic school or at any location or institution where instruction is offered in whole or in part to such nonpublic school students…”

Referenda specifically on vouchers were held in Michigan in 1978 and 2000. Vouchers were defeated by 74% to 26% in 1970 and by 69% to 31% in 2000.

Attempts were made to amend state constitutions to allow tax aid to church schools in Oregon in1972 (defeated by 61% to 39%), in Washington State in 1975 (defeated by 60% to 39%), in Alaska in 1976 (defeated by 54% to 46%), and in Massachusetts in 1986 (defeated by 70% to 30%). The relevant provisions of these last four states are as follows:

Oregon: “Article I, Section 5 … No money shall be drawn from the Treasury for the benefit of any religious or theological institution…”

Washington State: “Article I, Section 11. Religious Freedom … No public money or property shall be appropriated for or applied to any religious worship, exercise or instruction, or the support of any religious establishment…” And: “Article IX, Section 4 … All Schools maintained or supported wholly or in part by the public funds shall be forever free from sectarian control or influence.”

Alaska: “Article IX. Section 10. No tax shall be laid or appropriation of public money in aid of any church, or sectarian school…”

Massachusetts: “Article XVIII, Section 2. No grant, appropriation of the use of public money or property or loan of credit shall ever be authorized by the Commonwealth or any political subdivision thereof for the purpose of founding, maintaining or aiding any… institution, primary or secondary school or charitable or religious undertaking which is not publicly owned and under the exclusive control, order and supervision of public officers or public agents authorized by the Commonwealth…”

Wisconsin and Ohio are the first two states to have gotten away with instituting school voucher plans. Unfortunately their constitutions provide only weak and clumsy protection against use of public funds for church-related schools. It is instructive, however, to look at the constitutions of three states whose Republican legislatures have enacted voucher plans in 2011 and 2012, Indiana, Florida and Louisiana.

Indiana: “Article I, Section 4. No preference shall be given by law, to any creed, religious society, or mode of worship; and no man shall be compelled to attend, erect, or support, any place of worship, or to maintain any ministry, against his consent.” And: “Article I, Section 6. No money shall be drawn from the treasury, for the benefit of any religious or theological institution.”

Florida: “Article I, Section 3 … No revenue of the state or any political subdivision or agency thereof shall ever be taken from the public treasury directly or indirectly in aid of any church, sect, or religious denomination or in aid of any sectarian institution.”

Louisiana: “Article IV, Section 8. No money shall ever be taken from the public treasury, directly or indirectly, in aid of any church, sect or denomination of religion, or in aid of any priest, preacher, minister or teacher thereof, as such…” And: “Article XII, Section 13. No appropriation of public funds shall be made to any private or sectarian school.”

One can reasonably conclude that the Republican governors and legislatures of Indiana, Florida and Louisiana in 2011 and 2012 have shown no respect for their states’ constitutional restraints or for public opinion which, as we have seen, consistently opposes vouchers and their variants. Worse still, they did not have the decency to propose appropriate constitutional amendments so that voters could say yea or nay.

We come now to the question of how vouchers or their analogs square with the United States Constitution. The answer is murky.

As we have seen, in 1947 in Everson the Supreme Court held that “…No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion. Neither a state nor the Federal government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups and vice versa. In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between church and state’.” All nine justices agreed with that paragraph but the Court ruled 5-4 that New Jersey’s provision of bus transportation for church-related schools did not cross the line.

Five years later, in Zorach v. Clausen—a ruling upholding “released time” religious instruction during school hours but not on school premises—Justice William O. Douglas, who cast the deciding vote in Everson, wrote that in that case he had voted wrongly. But the damage was already done.

Although President John F. Kennedy favored federal aid for public schools and opposed tax aid for church-related schools, Congress was unable to get anything passed. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s sweep of the 1964 elections, however, allowed him to pass Kennedy’s aid to education package in 1965. Some aid for religion-related schools was included, though Leo Pfeffer, the leading authority on church-state law, insisted that federal aid without aid for church schools had had the votes to pass. Thought was given to a court challenge to federal aid to church schools, but something stood in the way, the question of “standing.” Since 1924 the Supreme Court did not allow mere taxpayers “standing” to sue in federal court to challenge public expenditures on First Amendment grounds. However, two rulings in 1968 opened the door. One, in the Flast v. Cohen case argued before the Court by Senator Sam Ervin (D-TN), granted taxpayer standing in Establishment Clause cases. But the other ruling upheld a New York law that allowed tax-paid textbook loans to church-related schools. The Court in these rulings effectively opened the door to legal challenges to tax aid for church schools but also sent a message that such challenges might not fare well. This dilemma delayed any federal court challenge to such aid.

Defenders of public education and religious freedom breathed easier when the Supreme Court ruled 8 to 1 in 1971 in Lemon v. Kurtzman against Pennsylvania and Rhode Island programs of tax aid to church-related schools. The Pennsylvania program allowed the state to “purchase” specified “secular educational services” while the Rhode Island plan authorized the state to supplement the salaries of church school teachers. It is important to note that Lemon was based on extensive showing of evidence of the pervasively religious nature of the schools.

Lemon was followed by similar decisions in 1973 in Committee for Public Education and Religious Liberty v. Nyquist and Sloan v. Lemon; in 1975 in Meek v. Pittinger; in 1985 in Grand Rapids v. Ball and Aguilar v. Felton; and in 1994 in Board of Education of Kiryas Joel v. Grumet.

The ground shifted, however, in 1997 when the court in Agostini v. Felton voted 5-4 to reverse its ruling in Ball and Aguilar, thanks to the addition to the Court of Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas by Presidents Reagan and Bush I.

A final blow was dealt in 2002 in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris when the same five justices who put George W. Bush in the White House in 2000 greenlighted the Ohio school voucher plan. In his stinging dissent Justice David Souter charged that the bare majority had simply ignored the great Everson ruling and decades of precedent. He added that “every objective underlying the prohibition of religious establishment is betrayed by vouchers,” and “as appropriations for religious subsidies rise, competition for the money will tap sectarian religion’s capacity for discord.” Also, “With the arrival of vouchers in religious schools… will go confidence that religious disagreements will stay moderate.”

In his dissent Justice Stephen Breyer warned of “the risk that publicly financed voucher programs pose in terms of religious social conflict.” He accused the majority of “turning the clock back” on “fundamental constitutional principles and adopting “an interpretation of the Establishment Clause that the Court rejected more than half a century ago.” He added, “I fear that this present departure from the Court’s earlier understanding risks creating a form of religiously based conflict potentially harmful to the nation’s social fabric.”

Sadly, the Supreme Court has ceased to be a dependable defender of a crucial First Amendment principle.

Conclusion

A century ago the Titanic sank beneath the waves of the North Atlantic. The blame, in retrospect, lay with the exuberance of the ship’s owners, flaws in design and workmanship, the shortage of lifeboats, and the captain’s failure to slow the ship in a region of known iceberg hazards.

In the America of the early 21st century we see the waters in Congress, state legislatures, and the media full of voucher icebergs of all sizes and descriptions. The waters are teaming with conservative sharks, pseudo-reformers and piranha pundits eager to wreck our laboriously evolved democratic public schools, take away the historic right to be free of government coercion to support religious institutions, and to erode the comity that allows our nation of people of incredibly diverse religious, political, ideological, ethnic, linguistic, and lifestyle diversity to live in reasonable harmony.

Vouchers are the tip of a school of icebergs every bit as dangerous as the one that sent the Titanic to the bottom. We are seeing public school budgets being slashed while public funds are being diverted to nonpublic schools not responsible to taxpayers and not subject to the reasonable regulations applicable to public schools. A quarter of America’s children live near or below the poverty line. Class sizes are being increased while programs for special needs children are being reduced. Class sizes of 30 to 40 kids are becoming more common when large-scale demonstrations, such as Tennessee’s STAR program, have shown that K-3 classes of just 15 students produce beneficial effects that last through high school graduation.

Insufficient attention is paid to the effects on school performance of poverty and its concomitants. Here is just one example among many. The National Center for Education Statistics has shown that while the gap between racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups is very slowly narrowing, it is still too wide. The 2011 science scores for eighth graders in the National Assessment of Educational Programs are 163 for whites, 129 for blacks, 137 for Hispanics, 159 for Asians, and 141 for Native Americans. Comparing income levels, free-lunch eligible eighth graders scored 137 while higher income students averaged 164. Yet the public schools serving poorer families are less well funded than those serving better off families.

Concern for religious freedom and church-state separation is not as high on the public radar as it once was.

With our Supreme Court no longer dependable as a defender of public education and religious liberty, We the People—as informed citizens, as voters, as contributors to political campaign and cause organizations, as educators and writers and just plain concerned citizens—must stand together to protect our schools and our basic freedoms.

Fortunately, more than 50 national education, religious, humanist, civil rights, civil liberties and other organizations have been working together for years in the National Coalition for Public Education to oppose efforts to channel public funds to nonpublic schools. But that is not nearly enough. The general public has to increase support for those organizations and others that are dedicated to this cause—Americans for Religious Liberty, the American Civil Liberties Union, People for the American Way, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, and the NAACP, to name but a few. Anything less would allow taxpayer dollars to support sectarian education and damage public education—a prospect that should trouble all Americans, religious or not.

Edd Doerr is president of Americans for Religious Liberty. A well-published writer, he is a former public school teacher (history, government, Spanish) and since 1966 has been a full-time professional in the religious freedom and church-state separation fields. He is author or editor of over 25 books and several thousand articles and columns.

Opponents of vouchers are repeatedly accused of being against “parent choice,” when nothing could be further from the truth. I wholeheartedly support the right of every parent to homeschool, or send their child to a private school – religious or otherwise – or to seek out online options, or whatever else they see fit. And in Oklahoma, they already have and always will have those options, fully protected by both popular opinion and explicit legislation.

Opponents of vouchers are repeatedly accused of being against “parent choice,” when nothing could be further from the truth. I wholeheartedly support the right of every parent to homeschool, or send their child to a private school – religious or otherwise – or to seek out online options, or whatever else they see fit. And in Oklahoma, they already have and always will have those options, fully protected by both popular opinion and explicit legislation.

As to yours truly, I’m working my way through Supreme Court cases related to “separation of church and state” as it

As to yours truly, I’m working my way through Supreme Court cases related to “separation of church and state” as it

Second, Ohio vouchers were part of a larger, heavily-funded series of

Second, Ohio vouchers were part of a larger, heavily-funded series of  Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn (2011) – United States Supreme Court

Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn (2011) – United States Supreme Court  LaRue v. Colorado Board of Education (2016) – Colorado Supreme Court

LaRue v. Colorado Board of Education (2016) – Colorado Supreme Court Citizens for Strong Schools v. Florida State Board of Education (2016) – 2nd Judicial Court of Florida

Citizens for Strong Schools v. Florida State Board of Education (2016) – 2nd Judicial Court of Florida Meredith v. Daniels (2013) – Indiana Supreme Court

Meredith v. Daniels (2013) – Indiana Supreme Court Louisiana Federation of Teachers v. State of Louisiana (2013) – Louisiana Supreme Court

Louisiana Federation of Teachers v. State of Louisiana (2013) – Louisiana Supreme Court Lopez v. Schwartz (2016) – Nevada Supreme Court

Lopez v. Schwartz (2016) – Nevada Supreme Court  Duncan v. State of New Hampshire (2014) – New Hampshire Supreme Court…

Duncan v. State of New Hampshire (2014) – New Hampshire Supreme Court…  State constitutions containing a

State constitutions containing a  We’ve been looking at Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the case most often cited when I’m researching vouchers and their constitutionality.

We’ve been looking at Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the case most often cited when I’m researching vouchers and their constitutionality.  Here’s a fun little game. Go to

Here’s a fun little game. Go to

As discussed

As discussed

This is where I wonder if the lack of actual

This is where I wonder if the lack of actual  Ohio’s program is constitutional because of all of the non-religious alternatives promoted by the state. If parental choice means a majority of kids end up in religious schools, that’s fine – as long as it’s the result of true choice. That means a variety of accessible options, both religious and non, public and private.

Ohio’s program is constitutional because of all of the non-religious alternatives promoted by the state. If parental choice means a majority of kids end up in religious schools, that’s fine – as long as it’s the result of true choice. That means a variety of accessible options, both religious and non, public and private.