Frederick J. Chiaventone, commenting on his own novel Moon of Bitter Cold:

Frederick J. Chiaventone, commenting on his own novel Moon of Bitter Cold:

One of the great delights of the historical novelist is the license to hang flesh on the bones of the actors and set the blood pumping through their veins. While the purist may decry this practice, others will find it useful and perhaps informative. There is a sense in which fiction can reveal more to us more of the truth than history in that historians are frequently constrained by their reliance on relics, some written, which are in themselves the products of imperfect and differently motivated human beings.

So while the historian can at best provide an objective account of the facts (however incomplete or imperfect), it is the province of the novelist to address not only the objective facts of a period and a people but their passions as well. To paraphrase Macaulay, it can be the difference between a topographical map and a painted landscape.

I like this, but Chiaventone does seem to lean towards a truth more at home in Kate Chopin than Doris Kearns Goodwin. He seems to promote moving past the factual in order to capture more important truths – which wistorical fiction can, and often does.

But in my mind that’s not the most important or purest sort of historical fiction. Let’s try another…

Richard Lee of the Historical Novel Society:

Historical fiction is the most primal, the most NATURAL of literary forms. If you look at all early literature in all cultures – even oral cultures – you find that the first stories that they tell are hero stories about their own ancestors and forebears. A man who boasts about himself is simply that – a boaster. But a man who boasts about his pedigree: well, he’s giving you REASONS why he is superior!

…Whether the story is fantastical, for example, the sort that proves a king’s descent from a god, or more earthy, like the Odysseus style of story, which praises tribal or national cunning, the impulse is the same: to present an idealized, dramatized form of the past.

So in all cultures, historical fiction is the most natural form of story-telling.

Think one step further and you will realize that this isn’t just the preserve of ancient peoples – it’s the way we tell stories of our own families. If we sit down to tell our children or grandchildren about someone they have never met – someone, perhaps, who was dear to us – we don’t try to sum up that person’s life, or give any balanced picture of the facts. We tell anecdotes. We tell stories that make SHAPES and CHARACTERS out of the past…

And we are not always too worried about whether or not these stories are precisely true – and certainly not in an historian’s “verifiable” sense of truth. We want them to be amusing to tell, to make the past come BACK to us, and to bring it alive for our listeners. And we make heroes… of those we have known. Anything, so long as what is dear to us is not forgotten. That’s historical fiction – and it is probably the most fundamental human literary need…

Stephen Crane, the author of the American Civil War classic The Red Badge of Courage, was once asked why he had chosen to write his book as fiction rather than history. You see he was a scholar. The reason, he said, was because he wanted to FEEL the situations of the War as a PROTAGONIST, not from the outside. And it was only by writing a novel that he could do this.

And this is what all historical fiction does. It makes us feel, as a protagonist, what otherwise would be dead and lost to us. It transports us into the past. And the very best historical fiction presents to us a TRUTH of the past that is NOT the truth of the history books, but a bigger truth, a more important truth – a truth of the HEART.

I like this as well. Although it starts off with an appreciation of the usefulness of some fictions, Lee steers the issue to one of probing history a bit through the way we write and attempt to capture it. We may twist the facts to grasp at reality, but we can just as desperately wrestle with the muse to better grasp the facts in all their complicated glory. Through historical fiction we can refuse to let it go until we’ve been enlightened, or granted some new words to call old things.

Michael Shaara, in the intro of The Killer Angels, says he wrote the book because he wanted to know “what it was like to be there, what the weather was like, what the men’s faces looked like.” He adds that since there were so many different historical interpretations of what went on at the Battle of Gettysburg, he based his narratives primarily on the letters, journal entries, and memoirs of the men who were there. This is in some ways the purest sort of historical fiction – using narrative form, reasonable gap-filling, and a light literary touch to reclaim experience, perspectives, people, and moments lost in the past.

Michael Shaara, in the intro of The Killer Angels, says he wrote the book because he wanted to know “what it was like to be there, what the weather was like, what the men’s faces looked like.” He adds that since there were so many different historical interpretations of what went on at the Battle of Gettysburg, he based his narratives primarily on the letters, journal entries, and memoirs of the men who were there. This is in some ways the purest sort of historical fiction – using narrative form, reasonable gap-filling, and a light literary touch to reclaim experience, perspectives, people, and moments lost in the past.

As novelizations of history have grown increasingly popular and taken greater liberties with the thoughts and words of their main characters, the genre continues to evolve. I believe it was David McCullough who suggested that “no harm is done to history by making it something someone would want to read.” I’m sure he’s right, but the more life we bring to dead people and events, the more possible it is that we’re creating our own reality rather than capturing theirs.

Still, I’ve found myself oddly engaged in topics I’d never have pursued through traditional history. I was unusually sympathetic to the struggles of Paul Du Chaillu to prove the existence of gorillas, and spent weeks tickled over the idea that Charles Dickens invented our modern concept of Christmas. I almost mourned over the death of President Garfield, about whom I knew almost nothing prior, and still ache for Alexander Graham Bell’s need to be useful and not merely famous. I found myself sucked into some small appreciation of the architectural risks taken at the 1893 World’s Fair, and how landscaping reflects larger cultural values – and I even kind of cared. Thus the power of novelization, of non-fiction fiction.

In short, my world is rather larger for having walked briefly in these worlds, something that would not have happened if I were left to imagine them based on available facts myself. Is that worth some risk in terms of absolute historical happening?

This entire series I’ve mostly strung together examples of things I can’t otherwise explain and the words of others saying what I’d have wished to say, but better. It seems only fitting, then, to conclude with my favorite commentary on the relationship between fact and story, by someone trying to capture history experienced firsthand. I’ve edited the passage somewhat for this blog.

Excerpt of “How to Tell a True War Story” from The Things They Carried (Tim O’Brien)

How do you generalize?

War is hell, but that’s not the half of it, because war is mystery and terror and adventure and courage and discovery and holiness and pity and despair and longing and love. War is nasty; war is fun. War is thrilling; war is drudgery. War makes you a man; war makes you dead.

The truths are contradictory. It can be argued, for instance, that war is grotesque. But in truth war is also beauty. For all its horror, you can’t help but gape at the awful majesty of combat. You stare out at tracer rounds unwinding through the dark like brilliant red ribbons. You crouch in ambush as a cool, impassive moon rises over the nighttime paddies. You admire the fluid symmetries of troops on the move, the great sheets of metal-fire streaming down from a gunship, the illumination rounds, the white phosphorus, the purply orange glow of napalm, the rocket’s red glare. It’s not pretty, exactly. It’s astonishing. It fills the eye. It commands you. You hate it, yes, but your eyes do not. Like a killer forest fire, like cancer under a microscope, any battle or bombing raid or artillery barrage has the aesthetic purity of absolute moral indifference – a powerful, implacable beauty – and a true war story will tell the truth about this, though the truth is ugly.

To generalize about war is like generalizing about peace. Almost everything is true. Almost nothing is true.

Though it’s odd, you’re never more alive than when you’re almost dead. You recognize what’s valuable. Freshly, as if for the first time, you love what’s best in yourself and in the world, all that might be lost. At the hour of dusk you sit at your foxhole and look out on a wide river turning pinkish red, and at the mountains beyond, and although in the morning you must cross the river and go into the mountains and do terrible things and maybe die, even so, you find yourself studying the fine colors on the river, you feel wonder and awe at the setting of the sun, and you are filled with a hard, aching love for how the world could be and always should be, but now is not…

The old rules are no longer binding, the old truths no longer true. Right spills over into wrong. Order blends into chaos, hate into love, ugliness into beauty, law into anarchy, civility into savagery. The vapors suck you in. You can’t tell where you are, or why you’re there, and the only certainty is absolute ambiguity.

In war you lose your sense of the definite, hence your sense of truth itself, and therefore it’s safe to say that in a true war story nothing is absolutely true.

Often in a true war story there is not even a point, or else the point doesn’t hit you until, say, twenty years later, in your sleep, and you wake up and shake your wife and start telling the story to her, except when you get to the end you’ve forgotten the point again. And then for a long time you lie there watching the story happen in your head. You listen to your wife’s breathing. The war’s over. You close your eyes…

You can tell a true war story by the questions you ask. Somebody tells a story, let’s say, and afterward you ask, “Is it true?” and if the answer matters, you’ve got your answer.

For example, we’ve all heard this one. Four guys go down a trail. A grenade sails out. One guy jumps on it and takes the blast and saves his three buddies.

Is it true?

The answer matters.

You’d feel cheated if it never happened. Without the grounding reality, it’s just a trite bit of puffery, pure Hollywood, untrue in the way all such stories are untrue. Yet even if it did happen – and maybe it did, anything’s possible – even then you know it can’t be true, because a true war story does not depend upon that kind of truth. Absolute occurrence is irrelevant. A thing may happen and be a total lie; another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth.

For example: Four guys go down a trail. A grenade sails out. One guy jumps on it and takes the blast, but it’s a killer grenade and everybody dies anyway. Before they die, though, one of the dead guys says, “The **** you do that for?” and the jumper says, “Story of my life, man,” and the other guy starts to smile but he’s dead.

That’s a true story that never happened…

Now and then, when I tell {one of my stories}, someone will come up to me afterward and say she liked it. It’s always a woman. Usually it’s an older woman of kindly temperament and humane politics. She’ll explain that as a rule she hates war stories; she can’t understand why people want to wallow in all the blood and gore. But this one she liked… Sometimes, even, there are little tears. What I should do, she’ll say, is put it all behind me. Find new stories to tell.

I won’t say it but I’ll think it.

I’ll picture Rat Kiley’s face, his grief, and I’ll think, You dumb *****.

Because she wasn’t listening.

It wasn’t a war story. It was a love story.

But you can’t say that. All you can do is tell it one more time, patiently, adding and subtracting, making up a few things to get at the real truth… It’s all made up. Beginning to end. Every ******* detail – the mountains and the river and especially that poor dumb baby buffalo. None of it happened. None of it. And even if it did happen, it didn’t happen in the mountains, it happened in this little village on the Batangan Peninsula, and it was raining like crazy, and one night a guy named Stink Harris woke up screaming with a leech on his tongue.

You can tell a true war story if you just keep on telling it. And in the end, of course, a true war story is never about war. It’s about sunlight. It’s about the special way that dawn spreads out on a river when you know you must cross that river and march into the mountains and do things you are afraid to do. It’s about love and memory. It’s about sorrow. It’s about sisters who never write back and people who never listen.

I’m not sure I’ve ended up anywhere better than when I started, but I did get some of this out of my system for now. I’m always open for comments, guest blog responses, or unbridled praise, so bring it on. But tell the truth.

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part I – Historical Myths

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part II – The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part III – Historical Fiction… Sort Of

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part IV – What’s Your Story?

Think one step further and you will realize that this isn’t just the preserve of ancient peoples – it’s the way we tell stories of our own families. If we sit down to tell our children or grandchildren about someone they have never met – someone, perhaps, who was dear to us – we don’t try to sum up that person’s life, or give any balanced picture of the facts. We tell anecdotes. We tell stories that make SHAPES and CHARACTERS out of the past…

Think one step further and you will realize that this isn’t just the preserve of ancient peoples – it’s the way we tell stories of our own families. If we sit down to tell our children or grandchildren about someone they have never met – someone, perhaps, who was dear to us – we don’t try to sum up that person’s life, or give any balanced picture of the facts. We tell anecdotes. We tell stories that make SHAPES and CHARACTERS out of the past… Though it’s odd, you’re never more alive than when you’re almost dead. You recognize what’s valuable. Freshly, as if for the first time, you love what’s best in yourself and in the world, all that might be lost. At the hour of dusk you sit at your foxhole and look out on a wide river turning pinkish red, and at the mountains beyond, and although in the morning you must cross the river and go into the mountains and do terrible things and maybe die, even so, you find yourself studying the fine colors on the river, you feel wonder and awe at the setting of the sun, and you are filled with a hard, aching love for how the world could be and always should be, but now is not…

Though it’s odd, you’re never more alive than when you’re almost dead. You recognize what’s valuable. Freshly, as if for the first time, you love what’s best in yourself and in the world, all that might be lost. At the hour of dusk you sit at your foxhole and look out on a wide river turning pinkish red, and at the mountains beyond, and although in the morning you must cross the river and go into the mountains and do terrible things and maybe die, even so, you find yourself studying the fine colors on the river, you feel wonder and awe at the setting of the sun, and you are filled with a hard, aching love for how the world could be and always should be, but now is not… I

I  Perhaps you or someone you love are familiar with popular inner narratives such as…

Perhaps you or someone you love are familiar with popular inner narratives such as… [T]he “liberal progress narrative”… goes like this: “Once upon a time, the vast majority of human persons suffered in societies and social institutions that were unjust, unhealthy, repressive, and oppressive. These traditional societies were reprehensible because of their deep-rooted inequality, exploitation, and irrational traditionalism…. But the noble human aspiration for autonomy, equality, and prosperity struggled mightily against the forces of misery and oppression, and eventually succeeded in establishing modern, liberal, democratic, capitalist, welfare societies.

[T]he “liberal progress narrative”… goes like this: “Once upon a time, the vast majority of human persons suffered in societies and social institutions that were unjust, unhealthy, repressive, and oppressive. These traditional societies were reprehensible because of their deep-rooted inequality, exploitation, and irrational traditionalism…. But the noble human aspiration for autonomy, equality, and prosperity struggled mightily against the forces of misery and oppression, and eventually succeeded in establishing modern, liberal, democratic, capitalist, welfare societies. Contrast that narrative to one for modern conservatism… [which] goes like this: “Once upon a time, America was a shining beacon. Then liberals came along and erected an enormous federal bureaucracy that handcuffed the invisible hand of the free market. They subverted our traditional American values and opposed God and faith at every step of the way…. Instead of requiring that people work for a living, they siphoned money from hardworking Americans and gave it to Cadillac-driving drug addicts and welfare queens.

Contrast that narrative to one for modern conservatism… [which] goes like this: “Once upon a time, America was a shining beacon. Then liberals came along and erected an enormous federal bureaucracy that handcuffed the invisible hand of the free market. They subverted our traditional American values and opposed God and faith at every step of the way…. Instead of requiring that people work for a living, they siphoned money from hardworking Americans and gave it to Cadillac-driving drug addicts and welfare queens. Sometimes our narratives do more than interpret or preserve information. Sometimes they cleverly replace what actually happened with more cooperative “facts” in order to maintain themselves. They then roll merrily along reflecting and

Sometimes our narratives do more than interpret or preserve information. Sometimes they cleverly replace what actually happened with more cooperative “facts” in order to maintain themselves. They then roll merrily along reflecting and  I wrote recently about the ‘urban legends’ of American History – the colorful stories which tend to root in significant events. Even factually flawed, these myths proffer illumination beyond the events themselves through their framing – or even their distortion – of the mere facts of a happening.

I wrote recently about the ‘urban legends’ of American History – the colorful stories which tend to root in significant events. Even factually flawed, these myths proffer illumination beyond the events themselves through their framing – or even their distortion – of the mere facts of a happening. And he also that had received the one talent came and said, Lord, I knew thee that thou art a hard man, reaping where thou didst not sow, and gathering where thou didst not scatter; and I was afraid, and went away and hid thy talent in the earth: lo, thou hast thine own.

And he also that had received the one talent came and said, Lord, I knew thee that thou art a hard man, reaping where thou didst not sow, and gathering where thou didst not scatter; and I was afraid, and went away and hid thy talent in the earth: lo, thou hast thine own. There stood, facing the open window, a comfortable, roomy armchair. Into this she sank, pressed down by a physical exhaustion that haunted her body and seemed to reach into her soul. She could see in the open square before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life. The delicious breath of rain was in the air. In the street below a peddler was crying his wares. The notes of a distant song which some one was singing reached her faintly, and countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves.

There stood, facing the open window, a comfortable, roomy armchair. Into this she sank, pressed down by a physical exhaustion that haunted her body and seemed to reach into her soul. She could see in the open square before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life. The delicious breath of rain was in the air. In the street below a peddler was crying his wares. The notes of a distant song which some one was singing reached her faintly, and countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves. Mr. & Mrs. Mallard are both entirely fictional, and the exact train accident described is unverifiable. On the other hand, upper middle class women of late 19th century America did often have stairs, and doors, and tumultuous bosoms. The ‘truth’ captured here is not unique to a particular time and place, but it was a specific feature of this time and place. It was also – not uncoincidentally – more or less Kate Chopin’s real life time and place.

Mr. & Mrs. Mallard are both entirely fictional, and the exact train accident described is unverifiable. On the other hand, upper middle class women of late 19th century America did often have stairs, and doors, and tumultuous bosoms. The ‘truth’ captured here is not unique to a particular time and place, but it was a specific feature of this time and place. It was also – not uncoincidentally – more or less Kate Chopin’s real life time and place. “That’s a very fine attitude for her to have, Boyd.” Mrs. Wilson restrained an impulse to pat Boyd on the head. “I imagine you’re all very proud of her?”

“That’s a very fine attitude for her to have, Boyd.” Mrs. Wilson restrained an impulse to pat Boyd on the head. “I imagine you’re all very proud of her?” A turtle and a rabbit are having a race on some pretense or other. The race begins, and the rabbit leaves the turtle far behind, as you would expect. The turtle just keeps right on moving as best he can, though, and after a time the rabbit gets lazy, or cocky, or both, and takes a lil’ nap – which is irrational in these circumstances but sets up the moral of the story.

A turtle and a rabbit are having a race on some pretense or other. The race begins, and the rabbit leaves the turtle far behind, as you would expect. The turtle just keeps right on moving as best he can, though, and after a time the rabbit gets lazy, or cocky, or both, and takes a lil’ nap – which is irrational in these circumstances but sets up the moral of the story. The rabbit is the cockiest and cruelest of the animals, and bullies the turtle into a race. The turtle has little choice, and after trying to dissuade the rabbit of the idea, they “agree” to test themselves the following morning. Just to keep things interesting, the rabbit adds a last-minute wager – the winner of the race will kill, cook, and eat the loser.

The rabbit is the cockiest and cruelest of the animals, and bullies the turtle into a race. The turtle has little choice, and after trying to dissuade the rabbit of the idea, they “agree” to test themselves the following morning. Just to keep things interesting, the rabbit adds a last-minute wager – the winner of the race will kill, cook, and eat the loser. Not all snakes are dangerous, for example, and a few may be quite helpful in some ways, but learning to tell hundreds of them apart, quickly, and in various situations, is time, labor, and brain space intensive. If I’m right, nothing happens; if I’m wrong, I could die – painfully.

Not all snakes are dangerous, for example, and a few may be quite helpful in some ways, but learning to tell hundreds of them apart, quickly, and in various situations, is time, labor, and brain space intensive. If I’m right, nothing happens; if I’m wrong, I could die – painfully. Ella’s agency and that of her ilk didn’t completely disappear, but it certainly evolved. Consider the Little Mermaid – who in both the Grimm and Disney versions of the story defies her father, entwines herself with the male of another species (or race), and makes a deal with dark forces to do so. She trades her voice – literally, which should absolutely horrify even the mildest feminist – for a shot at first base with the savior prince.

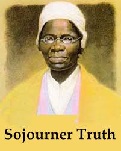

Ella’s agency and that of her ilk didn’t completely disappear, but it certainly evolved. Consider the Little Mermaid – who in both the Grimm and Disney versions of the story defies her father, entwines herself with the male of another species (or race), and makes a deal with dark forces to do so. She trades her voice – literally, which should absolutely horrify even the mildest feminist – for a shot at first base with the savior prince. One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the Convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity:

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the Convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity: Twelve years later, Frances Gage – a well-known reformer, abolitionist, and feminist in her own right – recounted the event somewhat differently. Gage was present at the convention, and was in fact the President to whom Truth addressed her initial request to speak. The version Gage recorded has become much better known, and is the one most often replicated, laminated, and recited when we speak of Truth today.

Twelve years later, Frances Gage – a well-known reformer, abolitionist, and feminist in her own right – recounted the event somewhat differently. Gage was present at the convention, and was in fact the President to whom Truth addressed her initial request to speak. The version Gage recorded has become much better known, and is the one most often replicated, laminated, and recited when we speak of Truth today. Maybe it was impossible to transfer the effect to paper, but Gage could try. I submit that she altered the facts in order to capture the truth. Recounting the event was inadequate, so she revamped it in order to get closer to what actually happened experientially. In her mind, I believe, the most important element of Truth’s speech that night was not the transcript, but the message and its impact.

Maybe it was impossible to transfer the effect to paper, but Gage could try. I submit that she altered the facts in order to capture the truth. Recounting the event was inadequate, so she revamped it in order to get closer to what actually happened experientially. In her mind, I believe, the most important element of Truth’s speech that night was not the transcript, but the message and its impact. Christopher Columbus has become a controversial figure in recent years. For some reason, the Native population of this grand land refuses to get overly excited about the man who first brought enslavement, disease, and near genocide to their ancestors. The basic mythology of his story has proven rather tenacious, however, even as his status as someone deserving their own holiday has come into dispute.

Christopher Columbus has become a controversial figure in recent years. For some reason, the Native population of this grand land refuses to get overly excited about the man who first brought enslavement, disease, and near genocide to their ancestors. The basic mythology of his story has proven rather tenacious, however, even as his status as someone deserving their own holiday has come into dispute. This brief oration is arguably the most important speech of the 19th Century – maybe in all of American history. In approximately three minutes, President Lincoln deftly redefined the purpose and scope of the Civil War and charged his audience and all future Americans with the “great task remaining before us” of extending full American-ness to all people, as apparently both the Founders and the dead soldiers being commemorated that day had intended – although that would have come as news to many of them, had they been alive to hear it.

This brief oration is arguably the most important speech of the 19th Century – maybe in all of American history. In approximately three minutes, President Lincoln deftly redefined the purpose and scope of the Civil War and charged his audience and all future Americans with the “great task remaining before us” of extending full American-ness to all people, as apparently both the Founders and the dead soldiers being commemorated that day had intended – although that would have come as news to many of them, had they been alive to hear it. Little wonder, looking at this speech a masterpiece of imagery, language, and manipulation for the good of mankind, and in so few words – that we can almost SEE the white dove descending from heaven to whisper the words in Lincoln’s ear. Less romantic is the idea that good writing – like good anything – is more often the product of years of effort, study, and practice.

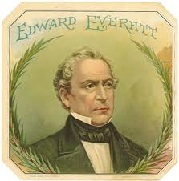

Little wonder, looking at this speech a masterpiece of imagery, language, and manipulation for the good of mankind, and in so few words – that we can almost SEE the white dove descending from heaven to whisper the words in Lincoln’s ear. Less romantic is the idea that good writing – like good anything – is more often the product of years of effort, study, and practice. Everett did indeed speak for somewhere around three hours, but that wasn’t considered excessive, nor was it tiring to hear. This was a pre-Xbox, pre-Facebook, pre-RockfordFiles nation. Life was in many ways slower and oration was high entertainment when done well – and Everett was the Paul McCartney of speechifyin’. A bit on the long side of his peak, he was nevertheless legendary for leading the audience through whatever rhetorical journey he chose, and by all accounts that day he was a master.

Everett did indeed speak for somewhere around three hours, but that wasn’t considered excessive, nor was it tiring to hear. This was a pre-Xbox, pre-Facebook, pre-RockfordFiles nation. Life was in many ways slower and oration was high entertainment when done well – and Everett was the Paul McCartney of speechifyin’. A bit on the long side of his peak, he was nevertheless legendary for leading the audience through whatever rhetorical journey he chose, and by all accounts that day he was a master.

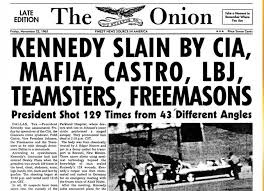

The idea that 9/11 was an inside job or that MLK was killed by the FBI is disturbing enough, but the alternatives are worse – that individuals or small groups of people, without the knowledge or control of those tasked with keeping us safe, did the worst of big bad things no one could anticipate or stop. We are creatures who want desperately to see order in our surroundings, and to claim some element of control over even the least controllable parts of our lives. A massive conspiracy by a large, powerful organization or sly government entity may be loathsome, but it’s not quite so terrifying as the unpredictability of the alternatives.

The idea that 9/11 was an inside job or that MLK was killed by the FBI is disturbing enough, but the alternatives are worse – that individuals or small groups of people, without the knowledge or control of those tasked with keeping us safe, did the worst of big bad things no one could anticipate or stop. We are creatures who want desperately to see order in our surroundings, and to claim some element of control over even the least controllable parts of our lives. A massive conspiracy by a large, powerful organization or sly government entity may be loathsome, but it’s not quite so terrifying as the unpredictability of the alternatives.