I previously covered some of the reasons land ownership was inseparable from representative government in the early American model, but I’ve left out at least one pretty important one.

I previously covered some of the reasons land ownership was inseparable from representative government in the early American model, but I’ve left out at least one pretty important one.

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Edmund Pendleton, August 1776:

You seem to have misapprehended my proposition for the choice of a Senate. I had two things in view: to get the wisest men chosen, & to make them perfectly independent when chosen. I have ever observed that a choice by the people themselves is not generally distinguished for its wisdom. This first secretion from them is usually crude & heterogeneous. But give to those so chosen by the people a second choice themselves, & they generally will chuse wise men…

Jefferson is suggesting a method of electing Senators similar to what was later done for the Presidency – a kind of electoral college. As is often the case with Jefferson, his hybrid of grand insight and colorful language is almost irresistible. He begins with typical Enlightenment precision followed by intentional understatement with a touch of ‘snide bastard’. The choice of the masses, left to their own direct democracy-type devices, “is not generally distinguished for its wisdom.”

Then the imagery – “the first SECRETION from them is usually CRUDE and HETEROGENEOUS…” Before you tab open dictionary.com, “heterogeneous” means diverse – in this case, an incoherent mess. And this is the guy who LIKES the common man – er… in theory. Kind of. Some days. From far away.

That the Senate as well as lower (or shall I speak truth & call it upper) house should hold no office of profit I am clear; but not that they should of necessity possess distinguished property… my observations do not enable me to say I think integrity the characteristic of wealth.

The Senate was intended to be the more austere, deliberative body – holding longer terms and intended as a balance on the more reactionary House of Representatives, elected every two years and thus presumably more responsive to the whims of the people. Jefferson’s parenthetical commentary is a nod to the superior role and trustworthy wisdom of the crude mess-secretors from a few sentences before.

The Senate was intended to be the more austere, deliberative body – holding longer terms and intended as a balance on the more reactionary House of Representatives, elected every two years and thus presumably more responsive to the whims of the people. Jefferson’s parenthetical commentary is a nod to the superior role and trustworthy wisdom of the crude mess-secretors from a few sentences before.

I said he was brilliant, not consistent.

In general I believe the decisions of the people, in a body, will be more honest & more disinterested than those of wealthy men: & I can never doubt an attachment to his country in any man who has his family & peculium in it…

We can’t trust the rich and powerful to run things, but neither can we trust the destitute. The landed citizen, however, in composite with others of his ilk – THAT’s a foundation. He is “attached” to his country – he has his family and his stuff here. Of course he wants the nation to do well – he has a vested interest uncharacteristic of those without such things.

If I buy my groceries at Wal-Mart and they go out of business, it’s inconvenient but not devastating. I may shop there, but I won’t organize the shelves or clean the bathrooms because that stuff is neither my job nor my problem. If, on the other hand, I not only work there but have stock in the company – my entire life savings and retirement, perhaps – you’ll find me helping people even on my day off, and replacing the toilet paper without begin asked. In that scenario, I NEED Wal-Mart to survive. I’m counting on it to succeed. Its destiny and mine are the same.

Substitute ‘Merica for Wal-Mart (not much of a stretch, really) and there you have it.

I was for extending the right of suffrage to all who had a permanent intention of living in the country. Take what circumstances you please as evidence of this, either the having resided a certain time, or having a family, or having property, any or all of them. Whoever intends to live in a country must wish that country well, & has a natural right of assisting in the preservation of it. I think you cannot distinguish between such a person residing in the country & having no fixed property, & one residing in a township whom you say you would admit to a vote…

The final reason land was so essential to early American democracy was that it established a stake in the success of the nation for those who held it. There are no stakes higher than protecting one’s home and sustenance – men will do almost anything to ensure success, even become informed voters.

Well, that’s the theory, anyway.

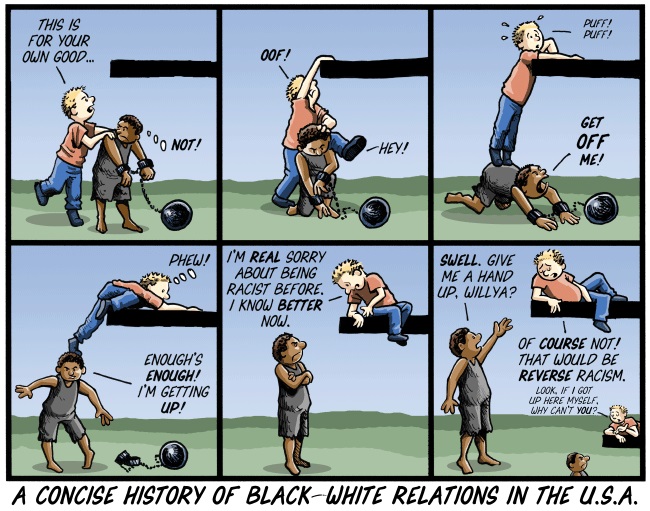

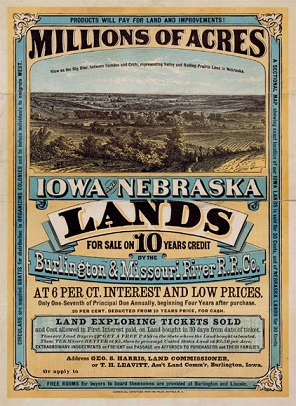

After the Civil War, many Freedmen believed they deserved – and that they had in fact been promised – “40 Acres and a Mule.” Some had actually been granted such at the unauthorized discretion of Union generals who, reasonably enough, took land from defeated plantation-owners and redistributed it to former slaves.

These few instances were reversed to smooth the transition into Reconstruction and maintain the almost cultish commitment Americans had to property rights – and, apparently, irony. The freedmen received nothing.

These few instances were reversed to smooth the transition into Reconstruction and maintain the almost cultish commitment Americans had to property rights – and, apparently, irony. The freedmen received nothing.

Well, that’s not entirely true. They received freedom. That was a pretty big deal. But freedom to do… what?

With no education, no land, no resources, no momentum – what the hell were they going to do?

Many stayed where they were, working the same land they’d been working, in exchange for food and shelter. Others left their former “masters” and wandered, either seeking loved ones from whom they’d been separated or simply wanting to go… somewhere else.

Many ended up working for white landowners under various arrangements. The South had just lost a rather brutal war – they didn’t have money to pay anyone. But food, shelter, a place to be… that they had. Eventually sharecropping and tenant farming were ubiquitous.

Freedmen didn’t have any land, or a realistic way to obtain land. Carpetbaggers from the North began establishing schools, the government had a few agencies, but overall opportunity was… limited. Just over a decade after the South surrendered the war, the North surrendered Reconstruction and brought their troops home in exchange for the Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes.

You all remember Hayes, right? A President for whom it was worth giving up the closest we’d ever come to realizing our founding ideals?

You all remember Hayes, right? A President for whom it was worth giving up the closest we’d ever come to realizing our founding ideals?

Yeah, me neither. And maybe we weren’t as close as we should have been in such a position – war won, Amendments ratified, South destroyed. But still…

Hayes fought bimetallism, stopped a railroad strike, and sped assimilation of Amerindians. In short, after Lincoln’s death, the Republican Party went to hell fairly rapidly. Their only real saving grace was that they weren’t Democrats.

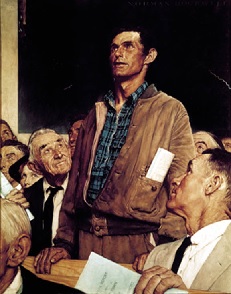

The freedman had gained everything – in theory. On paper, they were FREE! The men could vote! Land ownership! Education! Equality before the law! Unalienable rights, in your FACE!

Without land, though, they couldn’t provide for themselves. The system didn’t facilitate advancement via laboring for others – just ask the Lowell Girls, the Newsies, or any ox. Freedmen (or others without land) couldn’t do the things people had been conditioned to expect as a prerequisite for suffrage – for being a ‘full American’.

Despite written law, it became difficult to vote. It was impossible to gain economic ground, individually or as a community. Expression is severely limited when any unpopular thought can result in loss of livelihood. How does one maintain a sense of self against so much negation? At what point do we become our labels?

That’s the suffrage part. If Jefferson was correct about the spiritual and moral benefits of ‘laboring in the earth’, working the land of another may or may not have been worth partial divine credit. In terms of ‘vested interest’ in our national success, whatever support black Americans lent to their country came without terrestrial reciprocation.

That’s the suffrage part. If Jefferson was correct about the spiritual and moral benefits of ‘laboring in the earth’, working the land of another may or may not have been worth partial divine credit. In terms of ‘vested interest’ in our national success, whatever support black Americans lent to their country came without terrestrial reciprocation.

White men who succeeded under the system believed they deserved to succeed. Most had genuinely worked hard and made good choices by the standards of the time. It was not perhaps logical, but WAS very human, to see those who did NOT flourish as undeserving… obviously. We all want to be part of a good system, an ordered universe, and to be justified in whatever satisfaction we draw from our efforts. Generally, ‘facts’ adjust themselves to fit our paradigms rather than the reverse.

That’s not even a white thing – that’s just a people thing.

What began as a checklist for civic participation became the default measure of a man. What was intended to protect representative government from the incompetent or slothful became an anchor on those who didn’t fit certain checklists as of 225 years ago. You are unworthy. Not quite a full American – and thus not quite a full person.

The issue becomes your state of being rather than whatever rules you have or haven’t mastered, or whatever goals you haven’t met. It was self-perpetuating and self-reinforcing. It became circular.

And then it stopped being about land and started being about something else. A new ultimate requirement and cure-all, which must be made theoretically available to all for ‘democracy’ – such as it is – to survive.

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part I – This Land

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part II – Chosen People

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part III – Manifest Destiny

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part V – Maybe Radio

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part VI – Doomed to Repeat It

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part VII – Sleeping Giants

“Those who labor in the earth…” I suppose he could have just said “farmers,” but this paints a more vivid picture to set up where he’s going. It’s not about a role in the economy or the food chain – it’s about the agency of individuals, applied not merely to ground or soil but to the “earth”. It’s a wide-angle lens on an idealized way of life – Jefferson’s strength.

“Those who labor in the earth…” I suppose he could have just said “farmers,” but this paints a more vivid picture to set up where he’s going. It’s not about a role in the economy or the food chain – it’s about the agency of individuals, applied not merely to ground or soil but to the “earth”. It’s a wide-angle lens on an idealized way of life – Jefferson’s strength. Farmers worked 365 days a year. Soil still needing tilling on your birthday, cows needed milked on Christmas, and no matter how sick you might be, those crops weren’t going to reap themselves. It was labor-intensive and the hours were long, and yet after doing all you could do, all day every day – you waited.

Farmers worked 365 days a year. Soil still needing tilling on your birthday, cows needed milked on Christmas, and no matter how sick you might be, those crops weren’t going to reap themselves. It was labor-intensive and the hours were long, and yet after doing all you could do, all day every day – you waited. Jefferson had a distrust of bankers, stock markets, or anything financial industry-ish – so much so that he took great personal pride in never having the foggiest idea how to make his estate solvent (he died in substantial debt). Farmers raised essentials. They produced raw materials which could be woven into clothing, smoked for pleasure, eaten to survive. “Real wealth.”

Jefferson had a distrust of bankers, stock markets, or anything financial industry-ish – so much so that he took great personal pride in never having the foggiest idea how to make his estate solvent (he died in substantial debt). Farmers raised essentials. They produced raw materials which could be woven into clothing, smoked for pleasure, eaten to survive. “Real wealth.” Land ownership promotes solidity, character, ethereal virtues reflected in wise words and actions – valuable in and of themselves, sure, but especially necessary in a nation relying on the people themselves to provide beneficial leadership – directly or through their choices regarding representation.

Land ownership promotes solidity, character, ethereal virtues reflected in wise words and actions – valuable in and of themselves, sure, but especially necessary in a nation relying on the people themselves to provide beneficial leadership – directly or through their choices regarding representation. That he so easily adjusts his faith to accommodate current events I leave to you to interpret as you see fit.

That he so easily adjusts his faith to accommodate current events I leave to you to interpret as you see fit. Land was a big deal when our little experiment in democracy began. Why?

Land was a big deal when our little experiment in democracy began. Why?  So, in order to assure that everyone’s political voice is more or less equal, we’re going to have to deny a political voice to some – to those without the ability to provide for themselves. Otherwise, the entire representative system may be undermined through the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the indigent.

So, in order to assure that everyone’s political voice is more or less equal, we’re going to have to deny a political voice to some – to those without the ability to provide for themselves. Otherwise, the entire representative system may be undermined through the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the indigent. No help here from the ‘Father of the Constitution’. Apparently handing power over to men without land leads to either a tyranny of the masses (mob democracy) or a system in which the ignorant are led about by the manipulations of the wealthy and power-hungry.

No help here from the ‘Father of the Constitution’. Apparently handing power over to men without land leads to either a tyranny of the masses (mob democracy) or a system in which the ignorant are led about by the manipulations of the wealthy and power-hungry. Adams probably talked too much, but I do love how he steps his audience through his reasoning. It’s very Socrates, very Holmes, very Bill Nye the Government Guy. Franklin may have been the poster child of the Enlightenment in the New World, but Adams was its lesson planner and edu-blogger.

Adams probably talked too much, but I do love how he steps his audience through his reasoning. It’s very Socrates, very Holmes, very Bill Nye the Government Guy. Franklin may have been the poster child of the Enlightenment in the New World, but Adams was its lesson planner and edu-blogger. Power always follows Property. This I believe to be as infallible a Maxim, in Politicks, as, that Action and Re-action are equal, is in Mechanicks. Nay I believe We may advance one Step farther and affirm that the Ballance of Power in a Society, accompanies the Ballance of Property in Land.

Power always follows Property. This I believe to be as infallible a Maxim, in Politicks, as, that Action and Re-action are equal, is in Mechanicks. Nay I believe We may advance one Step farther and affirm that the Ballance of Power in a Society, accompanies the Ballance of Property in Land.