I’m sure it will surprise absolutely no one to learn that I’m not naturally the strict, by-the-book authoritarian type. In fact, I traditionally hate doing things that way – I really do.

I’m sure it will surprise absolutely no one to learn that I’m not naturally the strict, by-the-book authoritarian type. In fact, I traditionally hate doing things that way – I really do.

That doesn’t mean I think those who manage their classrooms (or families, or companies) that way are necessarily doing anything wrong. I’ve worked with teachers who care deeply about each and every child in front of them but would nonetheless rather burst into flames than hang a motivational poster, let alone bend a rule. It’s their very consistency that works for them. (It’s hard to feel picked on or abused when the Superintendent’s kid is serving the same after-school detention you are for being the same 23 seconds late after lunch a second time.)

One of the best pieces of advice I was given as a student teacher (or as anything else, for that matter) was from a soccer coach and social studies educator who wasn’t even my assigned mentor at the time. It’s been over twenty years, but I remember his name (Coach Kinzer), his voice, and even his face as he spoke. I even remember the school library where we talked while his kids worked on a project of some sort. (The project I don’t actually remember.)

That stuff they cover in teacher school, that’s fine, I guess, but you’ll quickly discover not everything works that way once you’re actually doing it. So, here’s my advice, if you want it:

Figure out what’s going to work for you in how you’re gonna run your classroom, and then stick to it. Don’t draw lines you can’t or won’t hold or make promises you can’t keep.

Now, me – I’m a hard-@ss. I don’t really see that working for you. But however you’re going to handle your classroom when it’s yours, make sure it’s something you’re willing to maintain all the time, because you can only fake it someone else’s way for just so long before it all falls apart.

I’ve had a few groups over the years which required more structure than others. And just because I prefer an informal approach to management and discipline doesn’t mean there aren’t critical boundaries. It’s not like I’m in tie-dye and wearing my gray hair in a ponytail every day, flipping the peace sign to the kids while they cuss me out, throw heavy objects, and light things on fire.

What it does mean is that I don’t tend to be rigid about things. Most issues I address only if they become a distraction or a safety issue, or when the school or district is particularly fixated on something. Historically, I’ve been pretty flippant with my kids as well. It’s high school, they’re practically people, and the more you abuse many of them, the more convinced they are that you’re establishing a true and lasting rapport. The crap I get away with saying just to poke at them would shock and horrify anyone who doesn’t actually work with young people, but for some reason it seemed to work.

What it does mean is that I don’t tend to be rigid about things. Most issues I address only if they become a distraction or a safety issue, or when the school or district is particularly fixated on something. Historically, I’ve been pretty flippant with my kids as well. It’s high school, they’re practically people, and the more you abuse many of them, the more convinced they are that you’re establishing a true and lasting rapport. The crap I get away with saying just to poke at them would shock and horrify anyone who doesn’t actually work with young people, but for some reason it seemed to work.

This choice comes with an obligation in return not to freak completely out when a student misreads the appropriate limits of such interactions and, in return, crosses lines which to the rest of us are still obvious. Sometimes they go from friendly barbs to tacky comments (which don’t crush my spirit but might negatively impact bystanders). Other times one of them will argue past the point of typical whining and it has to be shut down. The most common issue is that they simply haven’t developed a good natrual balance between “look at us building essential relationships” and the “shut up and get to work this is school.”

Each of those must be addressed, but if I’m going to play Mr. Flexible Cool-Teacher, I can’t respond to every poor choice by trying to become that “hard-@ss” Coach Kinzer was so good at. I’m particularly unwilling to escalate it beyond the doors of my classroom without multiple efforts to steer them back into the Realm of Reasonably Structured Learning.

It doesn’t always work. I’ve written referrals – even sent kids straight to an office a time or two, with a quick call and “paperwork to follow.” I’ve called parents, talked to administration, etc., when necessary… but I don’t like it. I’ve always figured I should be able to handle most of it with a little pluck and creativity. Well, that and their undying love for me based on how genuinely they know I care about them, whatever their weird personal issues. Honestly, I’ve always sort of taken pride in pushing my kids academically and personally based on love and mutual respect.

But you probably know that bit about what pride comes before…

I’m in a new school and a new district this year, teaching a new subject (English Language Arts – *waves-to-ELA-peeps*) This is not like any place I’ve worked before, and it probably makes sense that comes with some limitations on my tried-and-true approaches to relationships and classroom management.

I’m in a new school and a new district this year, teaching a new subject (English Language Arts – *waves-to-ELA-peeps*) This is not like any place I’ve worked before, and it probably makes sense that comes with some limitations on my tried-and-true approaches to relationships and classroom management.

Please understand, I really like the school. I like the kids (so far). I wouldn’t have taken the gig if I wasn’t 100% enamored with the head principal’s philosophy and approach to, well… everything in the school day. None of the learning curve I’m about to share is criticism of any of my new little darlings – and certainly not of my colleagues. They’re pretty much miracle-workers, based on what I’ve seen so far.

That said, this is not a group with whom my “loose management” style is working, or going to work. Not any time soon. In fact, despite my efforts to be Mr. Consistency from Day One, I’ve already experienced the natural consequences of presuming preparation they haven’t had, internal mechanisms they haven’t developed, and a rapport they don’t want. It hasn’t been a total disaster or anything, but…

Well, some of it has. But not mostly.

These aren’t bad kids. Most of them aren’t consciously trying to drive me out of the profession. Nor do I believe they need for me to be angrier or more uptight or unreasonably restrictive about every detail. Structure isn’t about being loud. It’s not emotional. In fact, you establish structure so that you don’t have to be loud or emotional. It may require “winning,” but winning isn’t the goal.

I’ve never bought into the whole “don’t smile until Christmas” thing, but there’s some truth to the idea that there are times it’s more important that your class be a solid place – reliable, predictable, perhaps even unbending – than a warm-fuzzy zone. There’s much truth to the idea that some kids desperately need structure, and may never have experienced clear rules with immediate consequences but zero ugliness or personal judgment. I’ve worked with teachers who are GREAT at that stuff – it’s just never been me.

It’s going to have to be this year. Not for me, and not for the state tests (which are a big issue in a school on all the wrong lists). I need to find that solidity. That almost detached, seemingly unsympathetic frame of mind necessary to have real school over time. It’s doable, and it’s the right thing to do in this case, for these students in this situation. It’s still nowhere near my natural way of doing things.

It’s going to have to be this year. Not for me, and not for the state tests (which are a big issue in a school on all the wrong lists). I need to find that solidity. That almost detached, seemingly unsympathetic frame of mind necessary to have real school over time. It’s doable, and it’s the right thing to do in this case, for these students in this situation. It’s still nowhere near my natural way of doing things.

Then again, it’s not supposed to be about me and my preferred way of doing things. It’s not really supposed to be about me, period. I read a teacher book, once – I know some stuff. And I have a blog; that makes me an EXPERT!

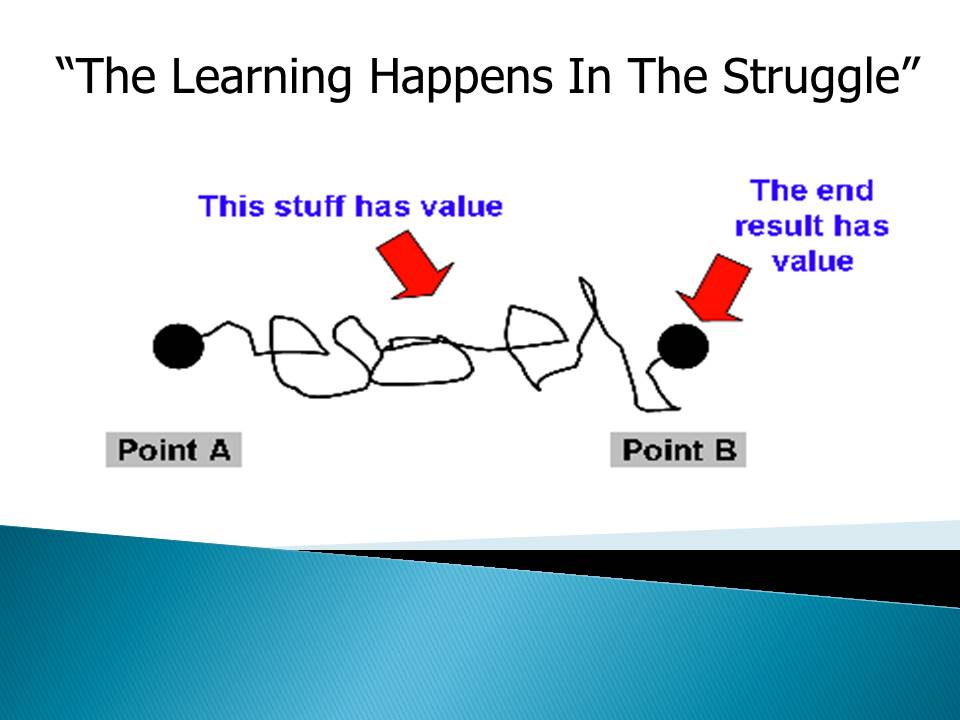

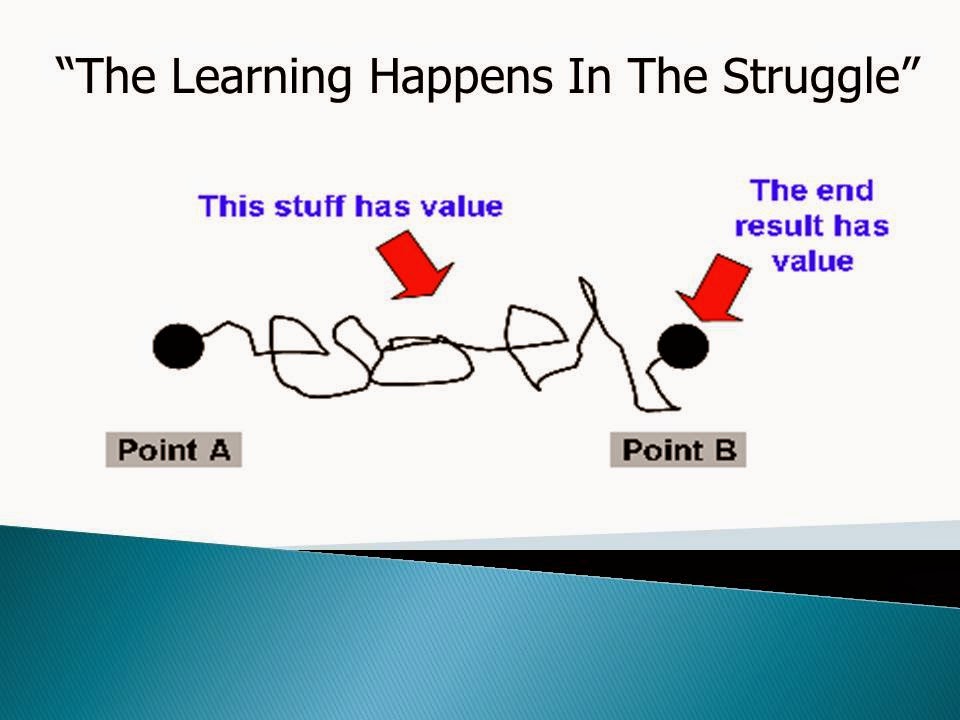

But this is, like… hard. I’ve already had enough things in recent years be hard. I’d like to sit back and wisely counsel others on dealing with adversity – I’ve no time for more of it personally. The learning happens in the struggle, sure… but can I not just read a book or something and we’ll call it even?

I’m not mad at anyone (well, myself sometimes) and I sure as hell don’t want to send any signals that I dislike or resent my kids – I don’t. I really, really don’t. (Some of them are already quite lovable, including the young man I’ve called security on twice already.) They need me to handle this well, and to be predictable, and to calmly make them mad by enforcing the policies, and to quietly assume the best about them when they’re trying to convince me otherwise, and to let them not like me because I’m so very “unfair.”

They need me to step back and not push relationship unless they decide they want it. To neither stereotype nor patronize them by believing I am in any way “down with kids.” (I’m so totally not.) Where my instinct is to connect, they need me to first be willing to contain. It kicks against everything I’ve loved about the gig for twenty years to so often and so calmly say, “no” and stand by it because anything else is chaos right now.

But I’m learning. And some of them are already asking some interesting questions. Not about English or History, unfortunately, but I suppose that will come. I don’t know them or their worlds and can’t read them the way I could so many others before, but in a way that’s probably just as well. This is going to take a while, and I should absolutely let it.

RELATED POST: Why Don’t You Just MAKE Them?

RELATED POST: Why Kids Learn (a.k.a. ‘The Seven Reasons Every Teacher Must Know WHY Kids Learn!’)

RELATED POST: Rules & Rulers

We’ve taught them to be completely helpless. We’ve trained them not to move until we tell them exactly what to do, and how, and then do it for them. The learning does indeed happen in the struggle, but how do they learn to struggle without, well… struggling?

We’ve taught them to be completely helpless. We’ve trained them not to move until we tell them exactly what to do, and how, and then do it for them. The learning does indeed happen in the struggle, but how do they learn to struggle without, well… struggling?

I feel myself giving in… letting go of the idealistic ‘oughta work’ and looking longingly towards the ‘would actually result in learning.’ I feel myself slipping off-program, avoiding my admins, and lying to my PLC about what I’m really doing in class that day.

I feel myself giving in… letting go of the idealistic ‘oughta work’ and looking longingly towards the ‘would actually result in learning.’ I feel myself slipping off-program, avoiding my admins, and lying to my PLC about what I’m really doing in class that day.