We did some practice test questions in our faculty meeting this morning.

We did some practice test questions in our faculty meeting this morning.

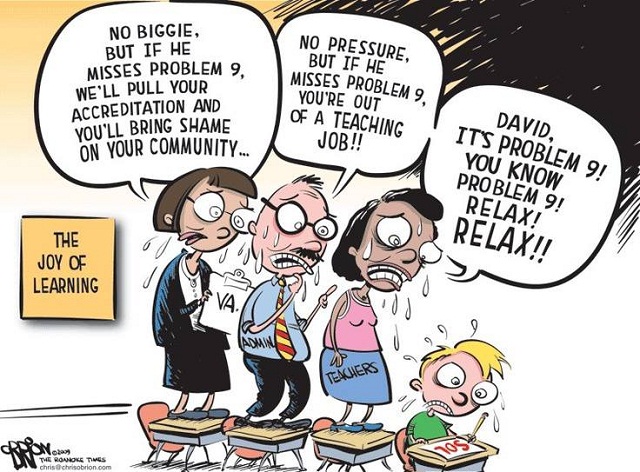

I get it. State testing season is upon us, and while I see the many amazing things happening in my new district, our recent scores have us on the state’s “naughty” list. The pressure is seriously building for the folks with slightly nicer desks than mine to turn things around.

State tests in Indiana take over the known world beginning in February – making Oklahoma’s “end of instruction” exams (which came two months or more before the end of instruction) seem somehow reasonable in comparison. If we’re going to be devoting our energies to persuading students of the value and importance of the damn things in the weeks to come, the reasoning goes, we should have some idea of what they actually look like.

I’ve already had a taste. This year is the first year the entire process is computerized. You’ve all seen the headlines in recent years about the number of times the whole system crashes halfway through this most modern and sophisticated of Teacher Effectiveness Measuring Systems; it seemed thus prudent to test the bandwidth a bit ahead of the official charade. Perhaps more importantly, the powers-that-be wanted students to be familiar with the procedures and formatting – the endless codes to be entered and ticket numbers to be verified, the bewildering joy conveyed by the mandated script over things like the availability of on-screen highlighting tools, and the way there’s ALWAYS that one kid who simply can NOT get logged in no matter what you try, leaving the entire room in frustrated limbo.

In short, my students all hate the damn tests months ahead of time.

Now, we can talk a good game about how important these are to graduation (they have to pass a certain number to get out of here with a decent flavor of diploma), but if my kids were long-term planners, they wouldn’t wait until the weekend after major projects are due to begin ignoring half of the instructions and doing them completely wrong. Insisting they be patient and maintain diligent enthusiasm over the opportunity to theoretically “demonstrate what they know” while I walk around trying to figure out why Enrique’s Passcode Verification Edu-Cipher keeps opening up the AP Latin Online Exam instead of High School Algebra is simply not persuasive.

After the first 15 minutes, I don’t really believe it myself.

In any case, teachers were given a sample math problem to solve this morning. Math teachers circulated to offer assistance after watch for shenanigans. My table was confronted with a serious dilemma on behalf of a fictional Timmy. Should he go with the cell phone plan that charges a monthly fee and then a small amount per text, or the plan with no monthly fee and a slightly higher amount per text? How many texts a month would make the first plan more advantageous?

Let’s set aside that cell phone plans don’t really work that way anymore; it’s a clear effort to take math and use it in a real world setting, even if that real world was in 2003.

For non-math people, we did rather well. We took the monthly fee of the first plan and divided it by the difference between per-text charges in the two. The answer was a nice round number – 300, I believe – and thus the number of texts at which the plans would cost the same. More texts than that and he should go with the monthly fee plan; fewer and he should stick with the higher per-text cost.

Look at us go! Real world math with a few scribbles on scratch paper! It took a few minutes to sort through the logistics, but we win at state testing.

Only we didn’t.

Our answer was correct, but we’d skipped the required step of writing out the equation necessary to work the problem. That’s what would be graded by the Electronic Masters. Did we know how to assign variables, and isolate ‘x’, and which rules applied, and all that?

Um… no, but we solved the problem. Not only that, we UNDERSTOOD our solution. Still, I suppose I could see some benefit to the expectation that students be able to translate that into the appropriate “language”…

Even that wasn’t enough, however. The real secret to success, once the problem was actually solved, was knowing how to use the on-screen tools and required answering box to enter the right symbols in the right order and leave the proper number of spaces in order to meet some pre-determined but loosely defined concept of what “showing your work” might actually look like to a minimum wage worker in Idaho looking at a key on a laminated sheet of some sort.

In other words, we failed high school math because we only knew how to use it to solve real-world problems, not how to make the test happy.

In my naivete, I thought the biggest challenge in math was still getting kids PAST the equations and into understanding how that math can actually be used. I thought the goal was to figure out how many tiles Savannah needs for her outdoor swimming pool, or the price point at which Carlos can afford fancy coffee once a week and still pay his rent. But it seems that’s not the goal at all.

The goal is to serve the machines. To nurture even deeper cynicism on the part of my kids about the actual point or value of even being her to begin with. To further bind their sense of identity and worth to their ability to game a rubric.

And I thought my internal tension over the time I spend focused on AP Exams was stressful; these poor math teachers! They love their subject – they’re really good at it – and they see the value, the fun, the joy, the depth! But if they’re going to qualify for those merit bonuses – or in some cases, keep their jobs at all – it has to all boil down to making the machines happy by pummeling their students into compliance.

Oh, and don’t forget to help the students remain relaxed and model some enthusiasm about taking the tests to begin with, of course.

It doesn’t help that behind my “still new here don’t make trouble still new here don’t make trouble” smile, I’m pretty sure the whole process is just another excuse to condemn public schools and undercut whatever progress we’ve made towards equity and more useful definitions of growth and excellence. While they don’t openly despise education with quite the fervor to which I grew accustomed in Oklahoma, this is still the Land of Pence and a VERY red state whose legislature simply goes to slightly more trouble to dress up their Trumpish loathing of all things social-contracty.

Even trying to ignore local politics, the undercurrent of seething resentment at ANY public money at all going towards the enlightenment of kids with blue collar parents and hard-to-pronounce last names is palpable. The hysteric bonds of ideology still chafe when again crushed (how surly they must be!) by the bitter angels of their nature.

Even assuming the best – that the state is acting out of willful ignorance rather than overt malice – I confess I am not looking forward to testing season. This has been a weird enough year and there are many things about my kids’ mindsets I wish I could magically transform – and no end to my personal failings as I’ve tried to lead them along a difficult path they have limited interest in treading.

And yet, I hate knowing they’ll be subjected to the monster in the weeks to come, and that there’s little I can do about it. For that matter, I don’t actually fault the district for their efforts to reshape some of their statistics, either. I suppose I could hold my breath that some new wave of rational political reform, untied to corporate overlords or bizarre ideology will sweep into power nine months from now, but that seems unlikely as well.

So I’ll keep trying to drag my little darlings to the water of life and hold their heads under until they discover the joys of learning, and hope that the clusterfoolery of standardized testing don’t exterminate what little progress we’ve made. If all else fails, I am confident that I am now fully qualified to get back into retail and help people like Timmy choose the best cell phone plan for him – as long as I don’t have to explain to a computer program how we figured it out.

RELATED POST: Am I Teaching To The Test?

RELATED POST: Actual Reflections (and too many questions)

RELATED POST: My Karma Ran Over My Dogma

I’m teaching AP World History this year. It’s a first for me, and at times has proved a bit of a challenge. Do you have any idea how many cultures and nations and movements and causes and changes there are in the entire history of mankind? All interacting and comparing and evolving and being complicated?! With maps and graphs and primary sources and EVERYTHING?!?!

I’m teaching AP World History this year. It’s a first for me, and at times has proved a bit of a challenge. Do you have any idea how many cultures and nations and movements and causes and changes there are in the entire history of mankind? All interacting and comparing and evolving and being complicated?! With maps and graphs and primary sources and EVERYTHING?!?! Possible scores range from 0 – 5, with 5 being the highest and 3 generally considered “passing.” The official rhetoric, though, is that it’s beneficial for students to take the course and the exam even if they score a 1 or 2, because of the experience it provides for them prior to college. (If I were sharing this with you as a parent or a teacher at one of my workshops, I’d now bust out a graph showing how much more likely kids are to stay in college and succeed while they’re there if they’ve taken a few AP classes in high school – whatever their scores on the exams. We could then quibble over those statistics and whether that correlation actually means what it looks like it means. I think it mostly does. Other smart people don’t. The resulting kerfuffle keeps Twitter interesting and makes drinking with other AP teachers far more entertaining than it might otherwise be.)

Possible scores range from 0 – 5, with 5 being the highest and 3 generally considered “passing.” The official rhetoric, though, is that it’s beneficial for students to take the course and the exam even if they score a 1 or 2, because of the experience it provides for them prior to college. (If I were sharing this with you as a parent or a teacher at one of my workshops, I’d now bust out a graph showing how much more likely kids are to stay in college and succeed while they’re there if they’ve taken a few AP classes in high school – whatever their scores on the exams. We could then quibble over those statistics and whether that correlation actually means what it looks like it means. I think it mostly does. Other smart people don’t. The resulting kerfuffle keeps Twitter interesting and makes drinking with other AP teachers far more entertaining than it might otherwise be.)

Oh! And we were “close reading.” We talked about close reading, and debated details from our close reading, and went back and reread our close reading more closely. I’m a fan of close reading, even in what is in some ways a survey course. And my district is at the moment uber-focused on improving overall close reading skills. Let me assure you, as bright as most of them are, and as much as I love their weirdness and wit, many of my students – even in AP – are not naturally strong in close reading.

Oh! And we were “close reading.” We talked about close reading, and debated details from our close reading, and went back and reread our close reading more closely. I’m a fan of close reading, even in what is in some ways a survey course. And my district is at the moment uber-focused on improving overall close reading skills. Let me assure you, as bright as most of them are, and as much as I love their weirdness and wit, many of my students – even in AP – are not naturally strong in close reading. Stopping to consciously think – to apply supportable facts to complicated questions, and to look closely at related information, to be intentional in the application of proclaimed priorities and values – that seems like a very good use of time, period – whatever the time period. Kinda makes me want to do it more often.

Stopping to consciously think – to apply supportable facts to complicated questions, and to look closely at related information, to be intentional in the application of proclaimed priorities and values – that seems like a very good use of time, period – whatever the time period. Kinda makes me want to do it more often. Our 3rd grade OCCT high stakes test starts Monday. This test, due to RSA and our Oklahoma legislature, requires our 8-year-old students to pass the test or being retained in 3rd grade (unless ridiculous and out of reach exemptions are met).

Our 3rd grade OCCT high stakes test starts Monday. This test, due to RSA and our Oklahoma legislature, requires our 8-year-old students to pass the test or being retained in 3rd grade (unless ridiculous and out of reach exemptions are met).