So I’ve written and published a book of important Supreme Court cases:

I’ve considered blogging about the process itself in hopes it might help others considering something similar, but I’m pretty sure the way I approach most things is roundabout and unnecessarily convoluted and would probably make any reasonable person want run from the room screaming. I will say this, though – it’s an amazing feeling to finally have it done. It’s also overwhelming the number of things that go wrong in the process itself and the volume of errors and problems you discover the first time your baby finally goes live – all of which can be traced back to me one way or the other.

Don’t worry, though – everything in it is fixed and practically perfect now. You should absolutely buy a few dozen copies. They make great gifts, look good on any bookshelf (at home, school, or other workplace), and they’re just the right thickness to go under unbalanced tables or chairs or give a little boost to your computer when live conferencing so your chin doesn’t look chubby.

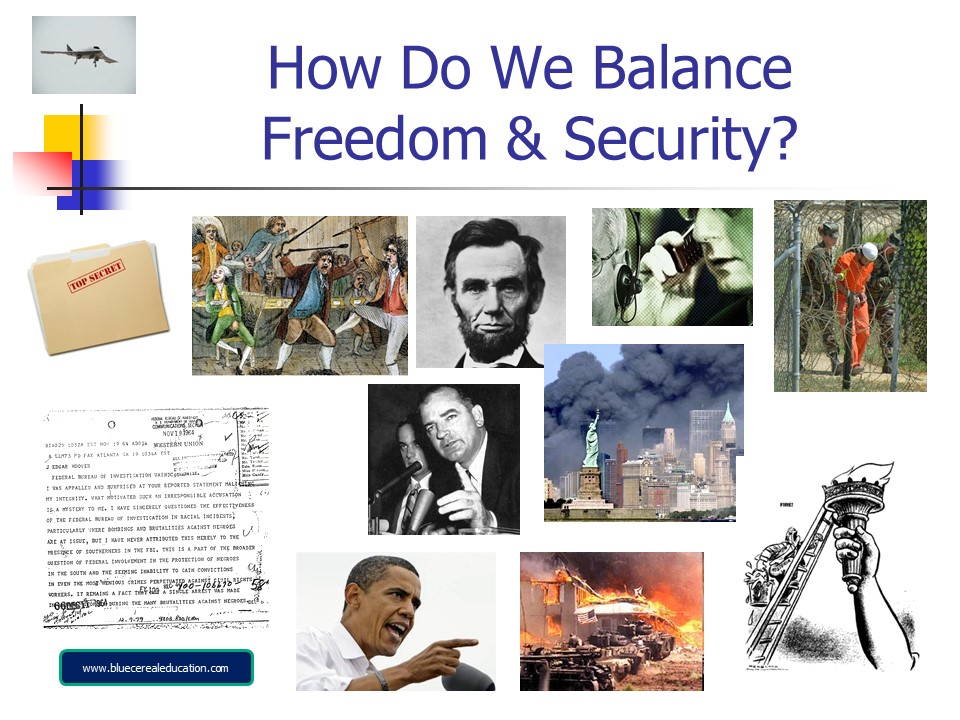

“Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases: Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About The Most Important Cases In Supreme Court History (I know – catchy, isn’t it?) was a project which began largely for my own reference and classroom use. Some of the material I posted here on Blue Cereal as early drafts. I wasn’t always focused on “landmark” cases – much like with anything in history, for every thread you pull, every question you pose, every rabbit you chase, there are something like a four-hundred and eleven new threads, questions, and rabbits begging to be pulled, posed, and chased – and not always in that order. It doesn’t require you to be particularly knowledgeable or profound; it’s a simple function of focusing on, well… anything, for any real length of time.

As I tell my students, when history is “boring,” the problem isn’t the history. It’s them.

At some point I began wondering if my efforts might prove useful to other educators in their various circumstances. I’m under no illusions about my own abilities, but there’s so much out there and so little time to really dig through it; you never really know what others might find helpful. I pulled together fifteen or so cases, excerpts from the Court’s written opinions, and some questions I’d written as “scaffolding” for my less-enthusiastic classes. I added a few more for sake of completion, along with some simple graphic organizers to manage major periods with multiple related cases.

I initially posted the final product to Teachers Pay Teachers along with a dozen other items. I have mixed feelings about TPT – I’m not against it, necessarily, but I’ve always preferred to simply share whatever I have that others might find useful. Then again, none of us seem to be against getting paid for leading workshops or writing teacher books promising this year’s magical cure to all the things, so I’m not sure why there’s so much faux outrage at those willing to offer up their own labor and creations for a few bucks so they can buy grandma that penicillin.

I sold a few items, but not enough to justify how I was feeling about it. My principles may be for sale, but I’d like to think the price is a little higher than what I was making.

Plus, I gradually realized several things which should have already been obvious. First, not every class needs the same sorts of questions or guidelines, even if they are studying some of the same cases. Second, if my goal was to self-publish the final product (which over time seemed more and more likely), I was limiting its usefulness by formatting it as a “workbook” of some sort. I mean, I read all sorts of nerdy things from other subjects or fields, but I’m not sure I’d actually pay for something if I thought half of the cost was for “homework” I wasn’t going to do. Finally, I’m in a one-to-one school. I tend to assume students can easily look up any relevant information not explicitly covered in the content. That means my questions aren’t always limited to stuff from the materials I’ve provided; they regularly include relevant background info one can easily Yahoo.

In short, my constant second-guessing became a bit silly. I deleted my TPT account and decided to write something which might appeal to students, teachers, or actual people in roughly equal proportions.

I combed several sets of state standards for American History and U.S. Government, plodded through the official Course Descriptions for APUSH and AP-GOV to make sure I included every case referenced in either (whether I’d have chosen those personally or not), and revised my summaries to make them as useful as possible for both students and teachers while remaining as accessible as possible to people who simply wanted to understand a little more about what the hell was going on with this or that issue in the news today.

I’m not saying the final product is perfect, but there’s a reason it took a year longer than I’d planned. (Plus, the final product really is perfect – I was just trying to be humble.)

Because this post is serving the dual purpose of sharing supplemental goodies while working in a subtle promo for you to open a new tab and buy the book, I’ll even share the final description from the (quite stylish) back cover:

Whether you’re a student trying to fake your way through an American History or Government class, a loyal American citizen seeking constitutional context for current events, or simply trying to look smart on a budget, “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases covers all the stuff you don’t really want to know (but for some reason have to) about 44 of the most important cases in our collective history. From midnight judges to gay marriage, internment camps to presidential shenanigans, you’ll find yourself looking more thoughtful and insightful just by leaving a few copies lying around. And if you actually read it, well… your credibility and self-confidence will soar and you’ll start decisively winning all of those arguments on social media. (Just tell them you have the book!)

Each featured case comes with historical context, the “three big things” you should remember, and an explanation of the decision and why we’re still talking about it today. Excerpts from the Court’s majority opinions are included, along with interesting bits from important concurring or dissenting opinions (so you can take in the Court’s reasoning in its own words). Additional “worth-a-look” cases are presented in compact form with brief highlights from the Court’s decision and a quick summary of the case and why it mattered. “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases is readable and fresh and covers everything likely to be on the test.

Take that last bit as literally or metaphorically as you wish.

Once everything was finally finished and published, I started thinking that it might still be useful to a few teachers to have those questions and graphic organizers and whatnot – especially if they weren’t something they were expected to purchase. I added a few more to go with the expanded format of the book, and here we are.

I’ve attached the same materials in two different versions. The “All” file, not surprisingly, has everything in a single PDF document. The “Questions” file has just the questions over case summaries and written opinions, and the remaining attachments are the various graphic organizers from the “All” file but in higher quality PDFs of their own. There’s also a summary of how the courts work which I didn’t write but have used in class from time to time.

Do with any or all of it as you see fit – or don’t. I genuinely hope some of it’s useful. If so, I’d love to know. If you create better stuff and you’re willing to share, send it along and I’ll post it.

In Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, Juliet laments that she cannot be with Romeo largely because of their last names. Their families are enemies and neither would ever accept the other into their homes. Standing on her balcony, unaware that he’s listening, she rejects the idea that names could be so important. Why should it matter what you’re called if you’re as awesome as Romeo – at least in Juliet’s eyes?

In Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, Juliet laments that she cannot be with Romeo largely because of their last names. Their families are enemies and neither would ever accept the other into their homes. Standing on her balcony, unaware that he’s listening, she rejects the idea that names could be so important. Why should it matter what you’re called if you’re as awesome as Romeo – at least in Juliet’s eyes?

Finally, there’s an additional, somewhat awkward motivation as well. I’m an old white guy whose hearing isn’t what it used to be. I genuinely want to learn my students’ names and say them correctly, but there are more each year that I never seem to quite get comfortable with. At the same time, it feels more important than ever that I demonstrate at least that much attention and respect to those whose names are most likely to give me trouble. With this assigment, I’ll have a reference as often as I need it to exactly how they want their name pronounced – because they’re the ones saying it.

Finally, there’s an additional, somewhat awkward motivation as well. I’m an old white guy whose hearing isn’t what it used to be. I genuinely want to learn my students’ names and say them correctly, but there are more each year that I never seem to quite get comfortable with. At the same time, it feels more important than ever that I demonstrate at least that much attention and respect to those whose names are most likely to give me trouble. With this assigment, I’ll have a reference as often as I need it to exactly how they want their name pronounced – because they’re the ones saying it.

Third – Reading supports content. ‘Going deep’ on a few key moments, issues, or individuals provides an ‘anchor’ in students historical understanding. It makes knowledge from before, during, and after that anchor ‘stickier’ – easier to understand, easier to remember.

Third – Reading supports content. ‘Going deep’ on a few key moments, issues, or individuals provides an ‘anchor’ in students historical understanding. It makes knowledge from before, during, and after that anchor ‘stickier’ – easier to understand, easier to remember.

(1) It makes history more meaningful and provides context, connecting various subjects under the ‘Social Studies’ umbrella all the way through today. Think of your favorite episodic TV show (’24’, ‘House of Cards’, ‘Game of Thrones’, etc.) Any given episode may have individual meaning and value, but that meaning and value increase dramatically if you understand the overall story arch.

(1) It makes history more meaningful and provides context, connecting various subjects under the ‘Social Studies’ umbrella all the way through today. Think of your favorite episodic TV show (’24’, ‘House of Cards’, ‘Game of Thrones’, etc.) Any given episode may have individual meaning and value, but that meaning and value increase dramatically if you understand the overall story arch.  Even a general awareness of these connections and relationships makes the specifics of each event richer and more meaningful. That in turn makes information easier to understand, recall, and apply. Any kid who’s played a ‘series’ of video games like Halo, Fallout, Assassin’s Creed, etc., can appreciate this connectivity.

Even a general awareness of these connections and relationships makes the specifics of each event richer and more meaningful. That in turn makes information easier to understand, recall, and apply. Any kid who’s played a ‘series’ of video games like Halo, Fallout, Assassin’s Creed, etc., can appreciate this connectivity.

One of the fundamental skills I try to teach my students is to ask good questions. And they don’t have to mean them.

One of the fundamental skills I try to teach my students is to ask good questions. And they don’t have to mean them.