NOTE: If you haven’t already done so, you should probably start with Part One of this post. I mean, I can’t force you or anything, but…

“Economic Substantive Due Process” in the Lochner Era

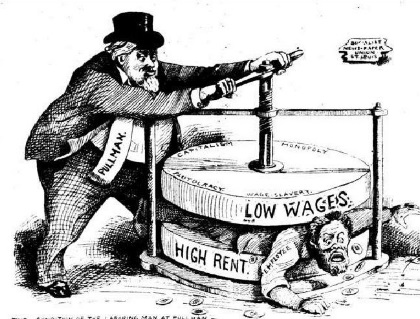

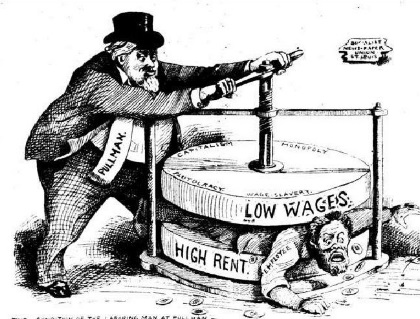

“School choice” wouldn’t emerge onto the national scene until after Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the various forays into moral corruption and social decay wouldn’t become staples of the nation’s highest court until a decade after that. The rest of the Lochner Era was largely about how freedom meant letting corporations do whatever they wanted to workers because those being exploited had just as much theoretical control over the outcome as their gilded overlords did. (They didn’t put it in those exact terms.) Between 1897 – 1937, the Supreme Court struck down nearly 200 different statues, most as violations of “freedom of contract” or other violation of “economic substantive due process.”

“School choice” wouldn’t emerge onto the national scene until after Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the various forays into moral corruption and social decay wouldn’t become staples of the nation’s highest court until a decade after that. The rest of the Lochner Era was largely about how freedom meant letting corporations do whatever they wanted to workers because those being exploited had just as much theoretical control over the outcome as their gilded overlords did. (They didn’t put it in those exact terms.) Between 1897 – 1937, the Supreme Court struck down nearly 200 different statues, most as violations of “freedom of contract” or other violation of “economic substantive due process.”

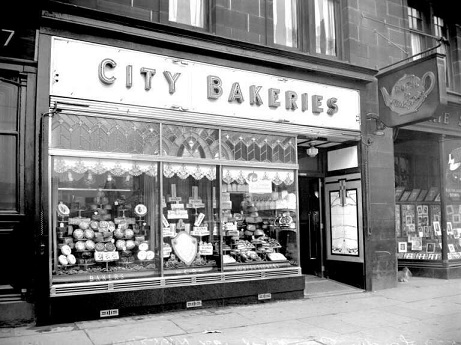

The Court acknowledged in principle that state and even sometimes federal government had some limited authority to regulate workplaces in order to promote safety and the general welfare, but only in cases involving explicit physical danger. Efforts to regulate mining, for example, might have a chance; restricting the hours during which one could safely bake bread, on the other hand… not so much.

Any such regulations should avoid restricting “market choices”; they couldn’t interfere with the ability of men to sign up for whatever working conditions they choose at whatever wages are available. The Lochner Era had little use for Congress’s claims to expanding authority under the Commerce Clause, making it one of those rare periods in U.S. history during which federal power didn’t simply expand at will. The Court was particularly unsympathetic towards labor unions during this period, regularly striking down laws facilitating union activities or offering workers more leverage in negotiations.

Other Major Cases of the Lochner Era

Here are a few of the more frequently cited cases of the period, although there were dozens of others which could just as readily demonstrate the ideology of the era:

Adair v. United States (1908) – Congress passed legislation in 1898 prohibiting “yellow dog contracts” in which workers agreed to forego union membership in order to obtain employment. When an interstate railroad company nevertheless fired an employee for joining a labor union, they argued that the Fifth Amendment protected them from being deprived of their liberty or property without due process (no doubt meaning the “substantive” variety). The Supreme Court agreed. While Congress had the right to regulate interstate commerce, that didn’t give them the right to interfere in the “liberty of contract” between employers and employees.

Adair v. United States (1908) – Congress passed legislation in 1898 prohibiting “yellow dog contracts” in which workers agreed to forego union membership in order to obtain employment. When an interstate railroad company nevertheless fired an employee for joining a labor union, they argued that the Fifth Amendment protected them from being deprived of their liberty or property without due process (no doubt meaning the “substantive” variety). The Supreme Court agreed. While Congress had the right to regulate interstate commerce, that didn’t give them the right to interfere in the “liberty of contract” between employers and employees.

Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918) – In 1916, Congress passed the Keating-Owen Bill, which attempted to standardize protections for children under the age of 16 (or 14 in some industries) working in factories or other labor-intensive industries. The Court declared Keating-Owen unconstitutional, insisting that Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce was intended to facilitate trade among the States, not stretched to regulate labor and production itself. Besides, the Court pointed out, the States had already addressed the issue in their own ways, as the Tenth Amendment allowed.

Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923) – The District of Columbia passed a minimum wage law for women and minors, complete with provisions for investigation and enforcement. The Children’s Hospital of D.C. protested that this was a violation of their “freedom of contract” as clearly established in Lochner v. New York (1905). The Supreme Court agreed and overturned the minimum wage legislation based on the same principles articulated in Lochner, adding that the law was “arbitrary” in that it imposed a uniform minimum wage regardless of women’s individual skills, occupations, wants, or needs. Besides, the Court added, with the passage of the 19th Amendment only a few years before, the idea that women required special protection was quickly becoming antiquated.

Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923) – The District of Columbia passed a minimum wage law for women and minors, complete with provisions for investigation and enforcement. The Children’s Hospital of D.C. protested that this was a violation of their “freedom of contract” as clearly established in Lochner v. New York (1905). The Supreme Court agreed and overturned the minimum wage legislation based on the same principles articulated in Lochner, adding that the law was “arbitrary” in that it imposed a uniform minimum wage regardless of women’s individual skills, occupations, wants, or needs. Besides, the Court added, with the passage of the 19th Amendment only a few years before, the idea that women required special protection was quickly becoming antiquated.

Carter v. Carter Coal Company (1936) – The Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935 was intended to establish national standards for the coal industry. It was not technically mandatory, but companies who agreed to pay the designated wages, limit working hours to those spelled out in the legislation, and follow the suggested pricing guidelines, received a substantial tax refund. The Court determined that Congress had (once again) overstepped its authority under the Commerce Clause. Employee wages and hours were part of production, not distribution or sales, and any relationship between the two was indirect at best. If individual states wished to regulate their industries in this way, that was fine – but nothing in the Constitution gave the federal government the right to step in on this level.

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937)

On its surface, West Coast Hotel was a fairly straightforward case. The State of Washington set a minimum wage for women and minors working in most professions. Elsie Parrish, who worked at a local hotel, sued for the difference between what she actually made and the legal minimum. Lower courts, following the precent set in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923), found in favor of the hotel – “freedom of contract” and “substantive due process” and all the usual staples of what was by this time forty years of “Lochner Era” jurisprudence.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, however, they found for Parrish and the State of Washington. The minimum wage was fine. Adkins was officially overturned. Just like that, the Lochner Era was over.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, however, they found for Parrish and the State of Washington. The minimum wage was fine. Adkins was officially overturned. Just like that, the Lochner Era was over.

West Coast Hotel marked a dramatic shift in the Court’s approach towards legislation regulating industry and protecting workers. This was not the result of a massive change of heart or mind by nine robed individuals, but a philosophical reversal on the part of a single Supreme – Justice Owen J. Roberts. Many of the infamous Lochner cases were decided by split votes, with 5 – 4 being the most common. West Coast Hotel was decided 5 – 4 as well, but 4 of the new 5 were the same core group who’d been overruled in similar cases for decades prior.

Why the change? Popular wisdom suggests it was a reaction to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s infamous “court packing plan” via the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. Tired of having so many of his New Deal efforts stymied or outright overturned by the Court, FDR proposed adding six additional justices over a period of several years – claiming he simply wanted to help the Court manage its extensive workload.

There was nothing unconstitutional about adding Justices to the Court, but even his supporters saw it as a rather obvious ploy to gain some leverage over a troublesome Supreme Court. Although the bill failed, perhaps Roberts sensed a change in the popular winds and decided it was time for the Court to pick its battles more carefully. Someone coined the phrase “the switch in time that saved nine” in reference to Roberts’ change of heart and the term stuck.

The Inglorious Demise of Economic Due Process

The Majority Opinion in West Coast Hotel, penned by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, accepted the State’s argument that women and minors were particularly vulnerable to exploitation by employers and that what was bad for women (many of them mothers) usually ended up being bad for society as well. This was the opposite of the “women don’t need no stinkin’ protection” approach of Adkins, but if you’re going to overturn a previous ruling, you might as well go all the way.

In an instant, the “economic substantive due process” went from being head cheerleader to the weird girl no one would invite to parties. It fell out of favor, seemingly inexplicably, and has been generally villified ever since. Lochner v. New York (1905) is now regularly lumped together on “worst ever” lists with cases like Scott v. Sandford (1857), Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), and Citizens United v. FEC (2010).

In an instant, the “economic substantive due process” went from being head cheerleader to the weird girl no one would invite to parties. It fell out of favor, seemingly inexplicably, and has been generally villified ever since. Lochner v. New York (1905) is now regularly lumped together on “worst ever” lists with cases like Scott v. Sandford (1857), Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), and Citizens United v. FEC (2010).

The idea that there are unenumerated rights just as essential to personal liberty as those spelled out explicitly, however, did not go away. Some would argue it had been there all along – hence the Ninth Amendment:

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Eventually “substantive due process” would re-emerge. It periodically popped up in the slew of “rights of the accused” cases for which the Warren Court is best-remembered, then – as previously mentioned – became a staple of both sexual freedom jurisprudence and a re-imagining of “religious liberty” far more aggressive than a generation ago. Because it relies on inference and historical interpretations, it’s both malleable and unpredictable. Perhaps the biggest error of the Lochner Era courts wasn’t their use of “unenumerated rights” in making their decisions, but their elevation of those inferred rights to a status which trumped all other considerations – economic, social, or legal.

RELATED POST: “Have To” History – United States v. Nixon (1974)

RELATED POST: “Have To” History – The Great Depression (1930s)

Crowded, dirty, dangerous cities and the evolving power of media to reveal “how the other half lives” brought about what would be remembered as the “Progressive Era.” Reformers began staking out victories, primarily at the municipal level – although by 1920 they could celebrate four new constitutional amendments as well. Both churches and charities were inspired by the idea that individuals, with a little help and “encouragement,” could improve. Individuals make up families, families make up societies… the world could become a better place, starting with the education of one child, the health of one mother, the reform of one man.

Crowded, dirty, dangerous cities and the evolving power of media to reveal “how the other half lives” brought about what would be remembered as the “Progressive Era.” Reformers began staking out victories, primarily at the municipal level – although by 1920 they could celebrate four new constitutional amendments as well. Both churches and charities were inspired by the idea that individuals, with a little help and “encouragement,” could improve. Individuals make up families, families make up societies… the world could become a better place, starting with the education of one child, the health of one mother, the reform of one man.

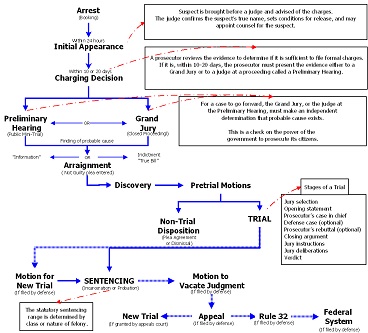

The most common understanding of this principle involves “procedural due process.” Anyone accused of a serious crime is guaranteed a fair trial before a jury of their peers. They have a right to an attorney and there are limits as to how the State may go about making the case against them. “Procedural due process” refers to the steps which must be taken and the hurdles which must be cleared before any level of government can take or limit your life, liberty, or stuff – whether the issue is property taxes, prison time, or capital punishment. The concept isn’t limited to criminal law; “due process” is also the steps your public school has to go through before suspending or expelling little Marco for his various violations, and why his guardians or other advocates have the right to challenge the system along the way.

The most common understanding of this principle involves “procedural due process.” Anyone accused of a serious crime is guaranteed a fair trial before a jury of their peers. They have a right to an attorney and there are limits as to how the State may go about making the case against them. “Procedural due process” refers to the steps which must be taken and the hurdles which must be cleared before any level of government can take or limit your life, liberty, or stuff – whether the issue is property taxes, prison time, or capital punishment. The concept isn’t limited to criminal law; “due process” is also the steps your public school has to go through before suspending or expelling little Marco for his various violations, and why his guardians or other advocates have the right to challenge the system along the way. What “substantive due process” protects, then, are what we sometimes refer to as “unenumerated rights” – protections implied by the written words of the Constitution and its Amendments, perhaps even inherent in them, but not spelled out as such. In the Lochner Era, this primarily referred to “economic substantive due process” – ideas like “freedom of contract” between companies and workers. It was during this same era, however, that two cases were decided largely on the basis of “substantive due process” which had nothing to do with workers rights or minimum wages. Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) involved the right of parents to determine the specifics of their child’s education and of educators to offer wildly controversial courses like foreign languages. Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) allowed parents to choose private schooling, religious or otherwise.

What “substantive due process” protects, then, are what we sometimes refer to as “unenumerated rights” – protections implied by the written words of the Constitution and its Amendments, perhaps even inherent in them, but not spelled out as such. In the Lochner Era, this primarily referred to “economic substantive due process” – ideas like “freedom of contract” between companies and workers. It was during this same era, however, that two cases were decided largely on the basis of “substantive due process” which had nothing to do with workers rights or minimum wages. Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) involved the right of parents to determine the specifics of their child’s education and of educators to offer wildly controversial courses like foreign languages. Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) allowed parents to choose private schooling, religious or otherwise. The dilemma of any effort to compile “must know” Supreme Court cases is deciding where to draw the line. If you narrow it to a list of 12, there are at least 3 or 4 others that really MUST be added in the name of consistency. If you expand the list to, say… 24, you’re sacrificing another half-dozen that should simply NOT be neglected if you’re to retain ANY credibility.

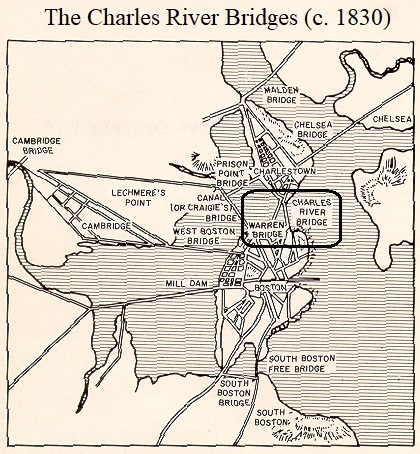

The dilemma of any effort to compile “must know” Supreme Court cases is deciding where to draw the line. If you narrow it to a list of 12, there are at least 3 or 4 others that really MUST be added in the name of consistency. If you expand the list to, say… 24, you’re sacrificing another half-dozen that should simply NOT be neglected if you’re to retain ANY credibility. In 1828, the state legislature granted a new charter to the Warren River Bridge Company (WRBC), who built a second bridge not all that far from the first. This bridge, however, was to be toll-free once initial costs were recovered and a reasonable profit earned for the company. Not surprisingly, people liked this bridge much better. The Charles River Bridge Company sued in state court, claiming the new charter violated their property rights and represented a broken contract by the State of Massachusetts. Not only was this very naughty, they argued, but it violated Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution, which says (among other things) that “no state shall… pass any… law impairing the obligation of contracts…”

In 1828, the state legislature granted a new charter to the Warren River Bridge Company (WRBC), who built a second bridge not all that far from the first. This bridge, however, was to be toll-free once initial costs were recovered and a reasonable profit earned for the company. Not surprisingly, people liked this bridge much better. The Charles River Bridge Company sued in state court, claiming the new charter violated their property rights and represented a broken contract by the State of Massachusetts. Not only was this very naughty, they argued, but it violated Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution, which says (among other things) that “no state shall… pass any… law impairing the obligation of contracts…” The Supreme Court rejected this line of reasoning and validated the “Granger Laws” as entirely appropriate and constitutional. Since before the founding of the United States, Chief Justice Waite explained, the foundational purpose of enlightened government is to support and regulate the social contract – each citizen giving up a small bit of autonomy for the larger good. In the end, this benefits everyone, including those making these minor sacrifices.

The Supreme Court rejected this line of reasoning and validated the “Granger Laws” as entirely appropriate and constitutional. Since before the founding of the United States, Chief Justice Waite explained, the foundational purpose of enlightened government is to support and regulate the social contract – each citizen giving up a small bit of autonomy for the larger good. In the end, this benefits everyone, including those making these minor sacrifices. 1. After it became clear that state-sponsored prayer was no longer a realistic option in public education, states began experimenting with the idea of a “moment of silence” during which students could pray (although no one had ever suggested that they couldn’t).

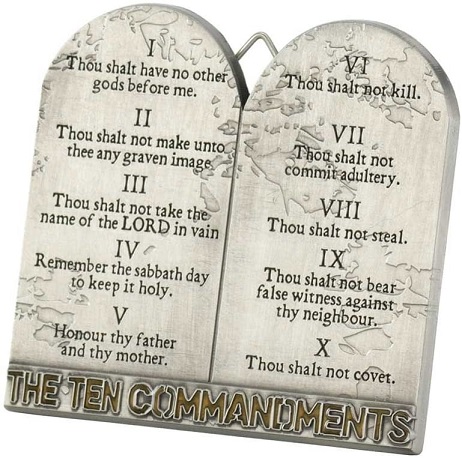

1. After it became clear that state-sponsored prayer was no longer a realistic option in public education, states began experimenting with the idea of a “moment of silence” during which students could pray (although no one had ever suggested that they couldn’t). The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.