Background

In Widmar v. Vincent (1981), the Supreme Court determined that when the University of Missouri (Kansas City) made its facilities available to extra-curricular groups outside of normal school hours, it created a “limited open forum.” If religious student organizations wished to use the facilities on the same terms as other groups, they must be allowed to do so. Not only was this NOT a violation of the Establishment Clause (as the University had feared), but denying equal access was a form of inhibiting students’ “free exercise” of religion. Justice Lewis Powell, writing for the majority in Widmar, explained it this way:

The question is not whether the creation of a religious forum would violate the Establishment Clause. The University has opened its facilities for use by student groups, and the question is whether it can now exclude groups because of the content of their speech. In this context, we are unpersuaded that the primary effect of the public forum, open to all forms of discourse, would be to advance religion…

It is possible – perhaps even foreseeable – that religious groups will benefit from access to University facilities. But this Court has explained that a religious organization’s enjoyment of merely “incidental” benefits does not violate the prohibition against the “primary advancement” of religion…

A few years later, the U.S. Congress – no doubt hoping to seize the moment – passed the Equal Access Act of 1984. It essentially took the standard expressed in Widmar and applied it to public schools. Any district which prevented students from having meetings or forming clubs on the basis of the “religious, political, philosophical, or other content of the speech at such meetings” would lose federal funding and receive a very nasty glare from D.C.

The Legislature had been frustrated in their previous efforts to work around or overturn the Court’s “anti-prayer” and “anti-Bible” decisions in Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington v. Schempp (1963), and despite his general popularity, President Reagan had made little progress on his promised Amendment to put the government back in charge of teaching kids what they should believe about Jesus. (OK, that’s not entirely fair. Reagan wanted an Amendment to leave it up to each state how to teach students about Jesus.)

The Equal Access Act included surprisingly practical guidelines. It distinguished between curricular organizations and those unrelated to specific coursework. Meetings had to be student-driven and not facades for outside groups coming in to run things. Perhaps most significantly, they had to be entirely voluntary and outside classroom hours. Before school was fine, lunch was fine, after school was fine – any time other clubs or groups could meet. Faculty “advisors” could attend (there are liability issues when minors are left to their own devices for extended periods of time) but not participate and certainly not lead.

All in all, it was a rather reasonable piece of legislation. That alone makes it something of a novelty in terms of Congress and public education.

Bridget Wants A Bible Study

Bridget Mergens was a student at Westside High School in Omaha, Nebraska. In 1985, she asked her principal for permission to form a Christian club at the school. They’d read and discuss the Bible, pray together, and enjoy what those on the inside call “fellowship.” Membership would be open to anyone, however, regardless of their beliefs – because, you know… school.

Bridget suggested they skip the required “faculty sponsor” part. (Presumably she was under the impression this might improve her chance for approval.) The principle said no. She went to the Associate Superintendent, who turned her down as well. Their initial argument (inferred from the court’s response) seems to have been that there could be no clubs without a sponsor, and that this club couldn’t have a faculty sponsor because it would violate the Establishment Clause. Bridget, being a persistent little thing (Luke 18:1-5), took her case to the School Board, which backed school administration.

This was stranger than it may at first seem, given several factors. One, this was Nebraska – a perennial “red state.” Two, this was happening in 1985, a mere year after the passage of the Equal Access Act – big news all across the country, and of particular interest to school officials who, as a general rule, don’t like being sued. Three, there’s no way to read the act as suggesting that religious clubs can’t have teacher sponsors – merely that they can’t participate in the actual discussions or activities. If administration actually played that angle (as the record suggests), it was nonsense… and they should have known it was nonsense.

So why would the district fight this particular request so vigorously? That’s part of what made (and makes) this particular issue so interesting.

Let’s Start A “Contemporary Legal Issues” Club

Mergens, with the support of a few friends and parents, filed suit in their district court. They argued that in addition to violating the Equal Access Act, the school was denying them their freedom of speech, association, and religion as guaranteed in the First Amendment (applied to the states via the Fourteenth). The district clearly had dozens of non-curricular clubs – including Chess Club, Rotary Club, a Scuba Diving Club (naturally very big in, um… Omaha), Photography Club, National Honor Society, Future Business Leaders of America, etc.

The district’s defense was innovative, and perhaps even sincere. All thirty or so of the clubs already established at Westside, they argued, were, in fact, curriculum-related. And since there were no extra-curricular clubs meeting on school property, the Equal Access Act did not apply. The Act assumed a “limited public forum” – and Westside hadn’t created one, legally speaking.

Rotary club? That was an extension of citizenship and public service, important school values and an essential part of each social studies course. Chess club? That was math and science and problem-solving, actual standards in several courses. Photography? Obviously a voluntary extension of art class. And scuba diving? Dude, physical education is a legit course – don’t write it off so easily. But this “Bible Club”? This was different. This was “extra-curricular.” Unlike Scuba Club.

As a backup, they asserted that even if the Equal Access Act did apply, it was unconstitutional – so it didn’t matter.

The district court accepted this reasoning and rejected Mergens’ claims. The case was appealed to the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals who reversed that decision and found in favor of Bridget’s Bible Club. The district – oddly tenacious, it seemed – appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case in 1990.

If You Give A Mouse A Bible Club…

The most likely explanation for Westside’s stubbornness had nothing to do with opposition to the kids’ faith. There’s at least one reference in court records suggesting that Westside’s principle encouraged the club to meet in the church next door to the school. The Court’s majority opinion mentioned that “the school apparently permits {students} to meet informally after school,” suggesting that at some point the school agreed not to chase them out of the building as long as they didn’t call themselves an official school club. This still meant being ignored in official club listings and left out of announcements, but it hardly evinced a hostility towards the general idea of kids getting together to study the Bible and pray.

On the other hand, what would be the implications of this “limited public forum” described in the Equal Access Act if the club were officially permitted? None of the existing clubs were particularly “issue-driven” or controversial. The school wasn’t wrong that they largely promoted existing school values and the usual “be a good citizen” stuff.

If the Protestants could have a club, however, then by law so could the Catholics. Next could come other faiths or issue-driven groups. Young Republicans. Young Democrats. Wiccans. Gay students. Black students. Atheists. Pro-life clubs. Pro-choice clubs. Oh god, Dungeons & Dragons could stage a comeback!

While the community would probably have been fine with students voluntarily meeting after school to read the Bible and pray, it’s not much of a stretch to imagine some would have been less-thrilled at the idea of their tax dollars supporting (in their minds) the Gay-Straight Alliance or Black Lives Matter (neither existed yet under those names, but the ideas were certainly nascent). Would the school approve Anarchy Club? Sodomites 4 Satan? MSNBC watch parties? At some point they’d reject a group based on its content and quite possibly be sued. At that point, all bets were off as to the fallout. Better to heed the advice of noted American philosopher Barney Fife: “Nip it, nip it, nip it in the BUD!”

In other words, it seems unlikely that the district fought against Bible Club because they didn’t understand the legal implications. More likely, they fought against it because they did.

NOTE: This post is an excerpt from “Have To” History: A Wall Of Education

There are certainly plenty of wonderful individual people of faith around, including many Christians.

There are certainly plenty of wonderful individual people of faith around, including many Christians. Notice the title – the “Star Spangled Banner Protection Act.” Because patriotism, like faith, apparently can’t survive without government propping it up by force. Note also the claim that American soldiers fight and die “for our flag.” Not our values, not our Constitution, and certainly not our people – for the cloth and the symbols and the rituals.

Notice the title – the “Star Spangled Banner Protection Act.” Because patriotism, like faith, apparently can’t survive without government propping it up by force. Note also the claim that American soldiers fight and die “for our flag.” Not our values, not our Constitution, and certainly not our people – for the cloth and the symbols and the rituals. The same basic approach was taken by

The same basic approach was taken by  In other words, the only reason to pass these laws is because those supporting them believe they ARE statements of faith. They DO matter in distinguishing America’s official religion (which they’re willing to pretend isn’t official in order to secure it as such) from all of those other belief systems (which have no place in public schools because of the First Amendment).

In other words, the only reason to pass these laws is because those supporting them believe they ARE statements of faith. They DO matter in distinguishing America’s official religion (which they’re willing to pretend isn’t official in order to secure it as such) from all of those other belief systems (which have no place in public schools because of the First Amendment).

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun.

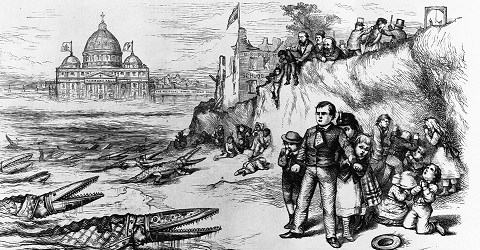

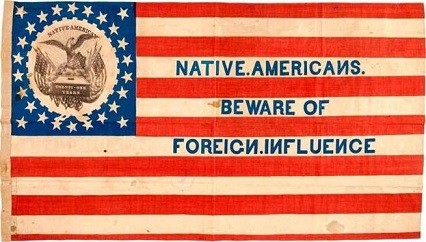

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun. The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname.

The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname. More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them.

More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them. Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.

Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.