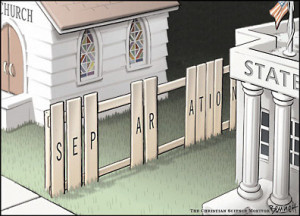

So far we’ve done a brief overview of the concept of a ‘Wall of Separation’ between church and state, and covered a few early Supreme Court Cases involving religion and public schools.

So far we’ve done a brief overview of the concept of a ‘Wall of Separation’ between church and state, and covered a few early Supreme Court Cases involving religion and public schools.

We looked at Everson v. Board of Education (1947) in which the Court determined it was perfectly acceptable for the state to reimburse parents for transportation costs of getting their children to school, whether public or private, sectarian or secular.

Then came Engel v. Vitale (1962), in which the Court made clear that the state could NOT require – or even promote – prayer in public schools as part of the school day. It was followed closely by Abington v. Schempp (1963) in which the same decision applied to the reading of Bible verses or the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer.

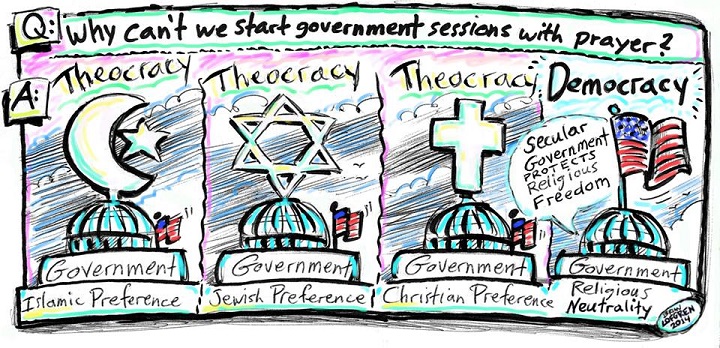

In both of these cases, the Court sought to prevent either the power of government or the foibles of politicians from unduly interfering in man’s reach for the Almighty. This was how they interpreted the Framers’ concerns as expressed in the First Amendment, applicable to the states via the Fourteenth.

In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), the Court established a “checklist” by which interested parties could determine whether or not something violated the “Establishment Clause” or the “Free Exercise Clause” of the First Amendment. While neither exclusive nor absolute, the “Lemon Test” is still regularly referenced today.

In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), the Court established a “checklist” by which interested parties could determine whether or not something violated the “Establishment Clause” or the “Free Exercise Clause” of the First Amendment. While neither exclusive nor absolute, the “Lemon Test” is still regularly referenced today.

In Stone v. Graham (1980), the Court said boo to the required posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms. The trend was clear – go easy on pushing your faith via mandatory common education.

But then Reagan took office, and a conservative revolution of sorts swept the nation. I don’t want to overstate the case – it’s not a Disney movie – but for those of you who weren’t there or don’t remember, the Reagan Era wasn’t just a presidential administration. It was a social movement, a political shift, a new dynamic comparable to Kennedy’s “Camelot” in impact – although very different in flavor.

Evangelicals were emboldened and the media and courts demonized as liberals – disgusting and dishonorable, both deceived and deceptive. They were dangers to the nation and everyone in it. Reagan wasn’t evil, at least by modern standards, but he did epitomize a sort of American Exceptionalism in Book-of-Revelation Sauce. The passion and self-righteousness of Ronnie and his adherents pre-empted reason, law, or precedent.

Evangelicals were emboldened and the media and courts demonized as liberals – disgusting and dishonorable, both deceived and deceptive. They were dangers to the nation and everyone in it. Reagan wasn’t evil, at least by modern standards, but he did epitomize a sort of American Exceptionalism in Book-of-Revelation Sauce. The passion and self-righteousness of Ronnie and his adherents pre-empted reason, law, or precedent.

It was in this climate that Alabama decided that Jesus and His legacy simply could not survive much longer without their assistance.

They’d already passed a 1978 law providing for a “moment of silence” each school day “for meditation.” They weren’t the only ones to test this route. Many states or districts instituted some variation of the “moment of silence” after Vitale (1962) and Schempp (1963) made it clear that institutional prayer or other overt Biblization was a no-no.

The “moment of silence” was as much a symbolic move as anything – it served and serves no real purpose or function beyond stepping right up to the line of church-state separation and daring the courts to do something about it. The legislators sponsoring the bill had said as much from the floor; it wasn’t a secret – they were running on their efforts to get prayer back into public schools. Extra credit if you can tell me why that alone should have been enough to invalidate the idea. {Hint: it rhymes with “Women Vest.”}

Alabama took things a step further in 1981, legislating that the moment of silence was to be used “for mediation and voluntary prayer.” Their momentum building, they upped their game yet again in 1982 and instructed teachers to lead “willing students” in a state-written prayer.

Ishmael Jaffree had three kids in Mobile County Public Schools – two in second grade and one in kindergarten. He protested the state-designed prayer, and had plenty of established case law on his side. But that’s not what struck me about his complaint.

Jaffree’s concerns stemmed not from abstract constitutional issues, but from his kindergartener being targeted by other kids for not participating in the prayers. His five-year-old was essentially bullied for not falling into line with state-mandated religious activities.

Jaffree’s concerns stemmed not from abstract constitutional issues, but from his kindergartener being targeted by other kids for not participating in the prayers. His five-year-old was essentially bullied for not falling into line with state-mandated religious activities.

He wasn’t alone. In a similar case going on in West Virginia at the same time, a Jewish student was challenged by peers for quietly reading during the “moment of silence.” He needed to pray, they told him, or he’d “go to hell with the rest of the Jews.”

Yes, the prayer was technically voluntary – but as anyone in education knows, “voluntary” can mean many different things. In this case, it was legal cover for bad law, an effort to create enough of a loophole to allow Alabama to belittle children for holding to their family’s religious beliefs in ways that didn’t harm or bother anyone, but without the state running afoul of those damned godless liberal judges.

And yes, there comes a time in life – even public school life – where students must be expected to grow up and accept that not everything works the way they want it to and not everyone is nice. We can’t and shouldn’t stop kids from ever saying an unkind word to one another.

And yes, there comes a time in life – even public school life – where students must be expected to grow up and accept that not everything works the way they want it to and not everyone is nice. We can’t and shouldn’t stop kids from ever saying an unkind word to one another.

That doesn’t mean, however, that the abuse has to be state-sanctioned. That doesn’t mean the state should throw the first pebble then disclaim responsibility when the very children it’s seeking to influence continue the work by throwing stones of their own.

In an interesting wrinkle, the federal district judge who heard this case as it worked its way through the system chose to ignore precedent and declared the laws perfectly constitutional, stating in his decision that “Alabama has the power to establish a State religion if it chooses to do so.” I’m all for waving your little flag at the tank as it rolls through the square, but this wasn’t the powerless standing up to the powerful – this was power trying to take more power.

And it wouldn’t have happened a decade before.

The South was ready to rise again through God, Guns, and the Gipper. Where’s that Confederate Flag and my 12-pack of Keystone?

I promise I’m not blaming every error of the modern world on Ronald Reagan – I was actually quite a fan. But he was wrong when early in his Presidency he proposed a constitutional amendment permitting organized prayer in public schools. He was wrong in his 1984 State of the Union when he asked why “freedom to acknowledge God” couldn’t “be enjoyed again by children in every schoolroom across this land?”

It’s always problematic when we use “freedom” to mean “giving me the power to force you to comply with my beliefs.” Students have always been free to acknowledge God in whatever schoolroom they happen to be. They’ve never been prohibited from praying at appropriate times or discussing their faith with other students, as long as we can have school along the way.

Imagine if President Clinton had insisted that school intercoms, choirs, and bands be used to broadcast, sing, and play Led Zeppelin exclusively, and at least once a day. Is that “bringing back freedom”?

It’s no dis on Zeppelin to suggest that some people much prefer Supertramp, or the Police, or even Etta James. Besides, you have to suspect that it wouldn’t be long before not just ANY Zeppelin would work. If your local Congressman is partial to the B-side of In Through The Out Door, then THAT becomes the only acceptable Zeppelin from here on out. You don’t even get “In The Evening” that way!

Of course you can disagree, but… why do you hate freedom? Are you a threat to our way of life? What are you, Disco?

On a personal note, I must confess that student liberties aside, I’m rather horrified by the use of the Christian faith as this sort of political tire iron. If the God they claim to serve is truly so helpless as to be somehow barred from hallways and classrooms of public schools around the nation, their efforts to facilitate his comeback are both tragic and unwise.

Surely the same Jesus who conquered Death and Hell isn’t lying around half-formed in a forest somewhere, waiting for Wormtail to bring him a few more ingredients for the Holy Cauldron or for Ms. Kravitz to read the right magic prayer out loud enough times.

It’s hard to imagine Paul the Apostle sitting along the road somewhere in Cyrprus, whining that he can’t preach the Gospel until some local legislature makes a rule requiring the Beatitudes be posted in the marketplace or mandating the 23rd Psalm be recited before any and all public lectures.

If your faith only works when government mandates that minors pay it hollow homage, you need a better faith.

But I should probably get back to the case…

While the Bible part and the praying part are consistently prohibited as violations of the Establishment Clause, the “Moment of Silence” has for the most part survived constitutional scrutiny, even while being acknowledged as an “accommodation” of faith – but not an “establishment” or “inhibitor” of faith.

That’s why in Oklahoma, every school day, students are given 5 – 7 seconds to “reflect, meditate, or pray” in any manner not disrupting or distracting those around them. I don’t know about you, but I feel MUCH closer to God as a result. If we were given, say… 12 seconds to work with, who knows what could happen?

RELATED POST: Should You Legislate the Bible?

RELATED POST: Missing the Old Testament

RELATED POST: Welcome to Atheist School!

On November 17, 1980, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Stone v. Graham – a case involving the required posting of the Ten Commandments on the wall of every classroom in Kentucky.

On November 17, 1980, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Stone v. Graham – a case involving the required posting of the Ten Commandments on the wall of every classroom in Kentucky.  *Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

*Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.

Cases don’t just magically appear in the Supreme Court. Except in rare circumstances, they begin as local disputes, sometimes working their way up through District Courts. By the time a case comes before the highest court in the land, it’s often been going on in some form for several years.

Cases don’t just magically appear in the Supreme Court. Except in rare circumstances, they begin as local disputes, sometimes working their way up through District Courts. By the time a case comes before the highest court in the land, it’s often been going on in some form for several years.

That doesn’t mean she’s not burning in eternal damnation even as we speak, but history is history. I’m just saying.

That doesn’t mean she’s not burning in eternal damnation even as we speak, but history is history. I’m just saying.  Oooh! This sounds interesting. It’s essentially the same accusation made against public schools in Oklahoma by our very own 21st century representatives a couple times a year.

Oooh! This sounds interesting. It’s essentially the same accusation made against public schools in Oklahoma by our very own 21st century representatives a couple times a year.

After Everson v. Board of Education (1947), fifteen years passed before the next important ‘religion and public schools’ case made its way to the Supreme Court. Whereas Everson dealt with transportation, Engel v. Vitale (1962) addressed the role of the supernatural in the classroom itself.

After Everson v. Board of Education (1947), fifteen years passed before the next important ‘religion and public schools’ case made its way to the Supreme Court. Whereas Everson dealt with transportation, Engel v. Vitale (1962) addressed the role of the supernatural in the classroom itself.

I can’t wait to hear what Governor Fallin and Preston Doerflinger determine about how much tithe God intends for you to pay, and where it should best be applied. And if you argue against them, you’re part of the godless liberalism pervading our once great nation. Good times!

I can’t wait to hear what Governor Fallin and Preston Doerflinger determine about how much tithe God intends for you to pay, and where it should best be applied. And if you argue against them, you’re part of the godless liberalism pervading our once great nation. Good times!