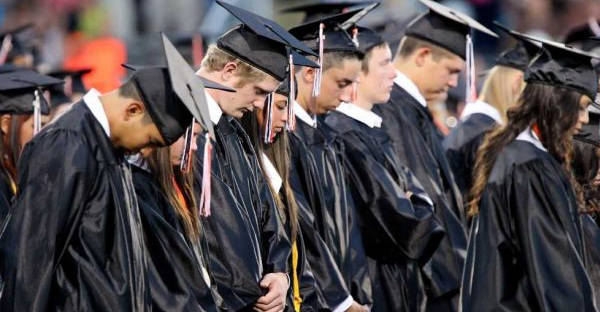

Graduation ceremonies provide an interesting dilemma when it comes to questions of church-state separation. They are inherently connected to public schooling and school officials, and participating students are largely accountable to those authorities during the event. At the same time, they often take place outside of school hours and off school grounds, and are in most cases technically voluntary – students need not attend in order to graduate.

Graduation ceremonies provide an interesting dilemma when it comes to questions of church-state separation. They are inherently connected to public schooling and school officials, and participating students are largely accountable to those authorities during the event. At the same time, they often take place outside of school hours and off school grounds, and are in most cases technically voluntary – students need not attend in order to graduate.

So are they bound by the same restrictions established in Engel and Abington and clarified by Wallace and other subsequent decisions? The short answer is yeah, they pretty much are.

In 1989, a middle school principle named Robert Lee in Providence, Rhode Island selected a local Rabbi to deliver prayers at a middle school graduation ceremony – which I guess is a thing in some places. Lee gave the Rabbi a pamphlet called “Guidelines for Civic Occasions,” which provided tips on “inclusiveness and sensitivity” and encouraged “non-sectarian” prayers.

Lee’s intentions were clearly good. The Rabbi followed the protocols. The same basic scenario was repeated annually across the state at both middle and high school events.

Daniel Weisman, a parent, objected to prayers of any sort being an official part of the ceremony. His concerns were overruled, and the Rabbi delivered a very nice benediction. Weisman took his case to the federal courts claiming this amounted to “establishment” and was thus unconstitutional.

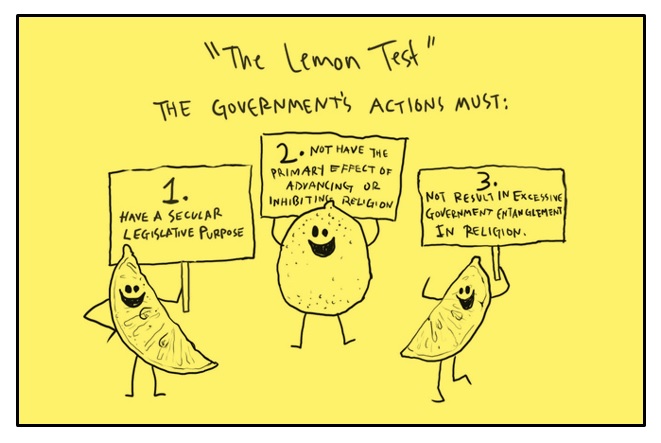

The federal district court applied the “Lemon Test” and agreed. The First Circuit Court of Appeals followed suit. Finally, in Lee v. Weisman (1992), the Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision confirmed the lower courts – you can’t do that.

Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote the Majority Opinion. I’ll try to limit myself to the highlights…

The school board… argued that these short prayers and others like them at graduation exercises are of profound meaning to many students and parents throughout this country who consider that due respect and acknowledgment for divine guidance and for the deepest spiritual aspirations of our people ought to be expressed at an event as important in life as a graduation…

Daniel Weisman filed an amended complaint seeking a permanent injunction barring petitioners, various officials of the Providence public schools, from inviting the clergy to deliver invocations and benedictions at future graduations… {A} a live and justiciable controversy is before us…

I kept that last bit because it’s fun to try to pronounce “justiciable.” Go ahead, try it a few times. Justishubble… JUST-is-a-bull… a LIVE and JUSTshibble controversy!

This is one of those awkward moments that I’m the only one having fun, isn’t it?

The court applied the three-part Establishment Clause test set forth in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). Under that test as described in our past cases, to satisfy the Establishment Clause a governmental practice must (1) reflect a clearly secular purpose; (2) have a primary effect that neither advances nor inhibits religion; and (3) avoid excessive government entanglement with religion…

There it is again – that zany ol’ Lemon Test. You should be getting used to it by now.

The court determined that the practice of including invocations and benedictions, even so-called nonsectarian ones, in public school graduations creates an identification of governmental power with religious practice, endorses religion, and violates the Establishment Clause…

Kennedy eventually addresses some of the arguments made in defense of graduation prayer:

State officials direct the performance of a formal religious exercise at promotional and graduation ceremonies for secondary schools. Even for those students who object to the religious exercise, their attendance and participation in the state-sponsored religious activity are in a fair and real sense obligatory, though the school district does not require attendance as a condition for receipt of the diploma…

In other words, just as in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), calling something “voluntary” doesn’t change all of the rules when it comes to minors and government coercion. He’ll come back to this theme later.

Kennedy then addresses the suggestion that prohibiting the state-sponsored prayer in some way interferes with the “free exercise” of those desiring its inclusion.

For those of you just tuning in, the First Amendment opens with not one, but two ‘freedom of religion’ clauses – the “establishment clause” (government can’t do anything to promote or encourage a particular religion) and the “free exercise clause” (government can’t do anything to discourage or limit a particular religion.) Government “neutrality” sounds pretty straightforward, but in practice these two goals are often in tension with one another.

For those of you just tuning in, the First Amendment opens with not one, but two ‘freedom of religion’ clauses – the “establishment clause” (government can’t do anything to promote or encourage a particular religion) and the “free exercise clause” (government can’t do anything to discourage or limit a particular religion.) Government “neutrality” sounds pretty straightforward, but in practice these two goals are often in tension with one another.

The principle that government may accommodate the free exercise of religion does not supersede the fundamental limitations imposed by the Establishment Clause. It is beyond dispute that, at a minimum, the Constitution guarantees that government may not coerce anyone to support or participate in religion or its exercise…

The State’s involvement in the school prayers challenged today… is as troubling as it is undenied. A school official, the principal, decided that an invocation and a benediction should be given; this is a choice attributable to the State, and from a constitutional perspective it is as if a state statute decreed that the prayers must occur. The principal chose the religious participant, here a rabbi, and that choice is also attributable to the State…

He continues, but the point is there were clearly a series of decisions made by adult representatives of the state which established required religious ceremonies for minors. The fact that the authorities in question made a good-faith effort to be as inclusive as possible doesn’t negate this reality.

Here’s a section I really like:

The First Amendment’s Religion Clauses mean that religious beliefs and religious expression are too precious to be either proscribed or prescribed by the State…

Just because you’re being all justiciable doesn’t mean you can’t keep it catchy, right?

It must not be forgotten then, that while concern must be given to define the protection granted to an objector or a dissenting nonbeliever, these same Clauses exist to protect religion from government interference.

James Madison, the principal author of the Bill of Rights, did not rest his opposition to a religious establishment on the sole ground of its effect on the minority. A principal ground for his view was: “{E}xperience witnesseth that ecclesiastical establishments, instead of maintaining the purity and efficacy of Religion, have had a contrary operation”…

This echoes a theme found in Engel and similar cases since – that government entanglement in religion is not only bad for those of other faiths, but it’s bad for the entangled faith as well. Cooperation between church and secular authority rarely ends well for either church or state.

This echoes a theme found in Engel and similar cases since – that government entanglement in religion is not only bad for those of other faiths, but it’s bad for the entangled faith as well. Cooperation between church and secular authority rarely ends well for either church or state.

Kennedy elaborates on other legalities before addressing my favorite argument by defenders of the prayers – that the world isn’t always going to cater to your weird beliefs or other druthers, so you’d better get used to it.

To endure the speech of false ideas or offensive content and then to counter it is part of learning how to live in a pluralistic society, a society which insists upon open discourse towards the end of a tolerant citizenry. And tolerance presupposes some mutuality of obligation. It is argued that our constitutional vision of a free society requires confidence in our own ability to accept or reject ideas of which we do not approve, and that prayer at a high school graduation does nothing more than offer a choice.

The actual case in question is a ‘middle school’ ceremony of some sort, but the Court had earlier acknowledged it was collectively addressing all varieties of such ceremonies.

By the time they are seniors, high school students no doubt have been required to attend classes and assemblies and to complete assignments exposing them to ideas they find distasteful or immoral or absurd or all of these. Against this background, students may consider it an odd measure of justice to be subjected during the course of their educations to ideas deemed offensive and irreligious, but to be denied a brief, formal prayer ceremony that the school offers in return. This argument cannot prevail, however. It overlooks a fundamental dynamic of the Constitution.

In other words, one might make an interesting argument that this is part of the educational process… but they’d be wrong. Or so Kennedy explains:

The First Amendment protects speech and religion by quite different mechanisms. Speech is protected by ensuring its full expression even when the government participates, for the very object of some of our most important speech is to persuade the government to adopt an idea as its own…

The method for protecting freedom of worship and freedom of conscience in religious matters is quite the reverse. In religious debate or expression the government is not a prime participant, for the Framers deemed religious establishment antithetical to the freedom of all.

Free speech, then, may often include the individual trying to persuade the government, or the government reasoning with or compelling the individual. Matters of faith, on the other hand, do not require the government’s approval or cooperation – nor should they be shaped by the whims of the state. Secular authority too easily throws the spiritual into the same blender as the mundane and vulgar, then hits “puree.” And that’s when it has good intentions.

Free speech, then, may often include the individual trying to persuade the government, or the government reasoning with or compelling the individual. Matters of faith, on the other hand, do not require the government’s approval or cooperation – nor should they be shaped by the whims of the state. Secular authority too easily throws the spiritual into the same blender as the mundane and vulgar, then hits “puree.” And that’s when it has good intentions.

Kennedy comes back to the question of whether or not students participating in the ceremony are being coerced into demonstrating support for beliefs contrary to their own. This part is going to provoke quite a backlash from the dissenting Justices, so sit up straight and pay attention, kids!

The undeniable fact is that the school district’s supervision and control of a high school graduation ceremony places public pressure, as well as peer pressure, on attending students to stand as a group or, at least, maintain respectful silence during the invocation and benediction. This pressure, though subtle and indirect, can be as real as any overt compulsion.

Of course, in our culture standing or remaining silent can signify adherence to a view or simple respect for the views of others. And no doubt some persons who have no desire to join a prayer have little objection to standing as a sign of respect for those who do. But for the dissenter of high school age, who has a reasonable perception that she is being forced by the State to pray in a manner her conscience will not allow, the injury is no less real.

There can be no doubt that for many, if not most, of the students at the graduation, the act of standing or remaining silent was an expression of participation in the rabbi’s prayer. That was the very point of the religious exercise. It is of little comfort to a dissenter, then, to be told that for her the act of standing or remaining in silence signifies mere respect, rather than participation…

Let’s skip for a moment to Justice Scalia’s dissent on this particular piece of the argument. “Dissent” is probably too mild – it’s really more of an eruption of disdain.

Let’s skip for a moment to Justice Scalia’s dissent on this particular piece of the argument. “Dissent” is probably too mild – it’s really more of an eruption of disdain.

The Court declares that students’ “attendance and participation… are in a fair and real sense obligatory.” But what exactly is this “fair and real sense”? According to the Court, students at graduation who want “to avoid the fact or appearance of participation” in the invocation and benediction are psychologically obligated by “public pressure, as well as peer pressure… to stand as a group or, at least, maintain respectful silence” during those prayers…

This assertion – the very linchpin of the Court’s opinion – is almost as intriguing for what it does not say as for what it says. It does not say, for example, that students are psychologically coerced to bow their heads, place their hands in a Durer-like prayer position, pay attention to the prayers, utter “Amen,” or in fact pray. (Perhaps further intensive psychological research remains to be done on these matters)…

Is that… sarcasm pouring forth from a pen of the Divine Nine?

The Court’s notion that a student who simply sits in “respectful silence” during the invocation and benediction (when all others are standing) has somehow joined – or would somehow be perceived as having joined in the prayers is nothing short of ludicrous. We indeed live in a vulgar age. But surely “our social conventions” have not coarsened to the point that anyone who does not stand on his chair and shout obscenities can reasonably be deemed to have assented to everything said in his presence…

Stuff like this is why Scalia’s loss was so devastating, whatever one’s politics. This is glorious dissent.

But let us assume the very worst, that the nonparticipating graduate is “subtly coerced” … to stand! …

{M}aintaining respect for the religious observances of others is a fundamental civic virtue that government (including the public schools) can and should cultivate – so that even if it were the case that the displaying of such respect might be mistaken for taking part in the prayer, I would deny that the dissenter’s interest in avoiding even the false appearance of participation constitutionally trumps the government’s interest in fostering respect for religion generally.

Clearly Scalia and the three other Justices who signed off on this dissent are NOT impressed by the Court’s decision. Their outrage is both palpable and a tad pissy.

Clearly Scalia and the three other Justices who signed off on this dissent are NOT impressed by the Court’s decision. Their outrage is both palpable and a tad pissy.

But back to the majority opinion…

Kennedy proceeds to address the state’s argument that these are harmless little ceremonial prayers, not enough to constitute “establishment.” He finds this contradicts the state’s own arguments regarding the importance of prayer. Kennedy cycles through several of his points again with renewed vigor before hitting his home stretch with a somewhat defensive denouement too long to reproduce here. Well, except for this bit:

Our jurisprudence in this area is of necessity one of line-drawing, of determining at what point a dissenter’s rights of religious freedom are infringed by the State…

“Look! We have to draw the lines somewhere, OK?! This isn’t an exact science, we’re talking about real people and some rather complicated situations, so just back off, haters!”

OK, maybe I’m over-interpreting his tone here.

And he’s not wrong. A review of related jurisprudence over the previous half-century certainly confirms his suggestion that such lines can be tricky. The Court is seeking balance, which sometimes means a frustrating lack of predictability.

As suggested earlier, Justice Scalia’s dissent really deserves a post of its own, but I’ll limit myself to a few brief excerpts, with minimal commentary. But, oh my – Antonin!

{Today’s opinion} is conspicuously bereft of any reference to history. In holding that the Establishment Clause prohibits invocations and benedictions at public school graduation ceremonies, the Court – with nary a mention that it is doing so – lays waste a tradition that is as old as public school graduation ceremonies themselves, and… an even more longstanding American tradition of nonsectarian prayer to God at public celebrations generally.

This is the case most likely to be made when pushing one’s own version of faith into the public sphere – tradition and history. It’s Christianity’s strongest claim to why it should be treated differently than other faiths – although they’ll never quite come out and put it that way. It’s effective because there’s truth in it – it’s a mistake to try to tease out every last thread of spirituality in our history and culture for fear we’re not being “neutral” enough.

Hmm… I guess that’s more than “minimal commentary.” Sorry.

As its instrument of destruction, the bulldozer of its social engineering, the Court invents a boundless, and boundlessly manipulable, test of psychological coercion… Today’s opinion shows more forcefully than volumes of argumentation why our Nation’s protection, that fortress which is our Constitution, cannot possibly rest upon the changeable philosophical predilections of the Justices of this Court, but must have deep foundations in the historic practices of our people…

The Court’s argument that state officials have “coerced” students to take part in the invocation and benediction at graduation ceremonies is, not to put too fine a point on it, incoherent.

So… I’m thinking he disagrees on this one.

The Court today demonstrates the irrelevance of Lemon by essentially ignoring it, and the interment of that case may be the one happy byproduct of the Court’s otherwise lamentable decision. Unfortunately, however, the Court has replaced Lemon with its psycho-coercion test, which suffers the double disability of having no roots whatever in our people’s historic practice, and being as infinitely expandable as the reasons for psychotherapy itself…

Despite the rhetorical spittle flinging everywhere, Scalia concludes with strong, slightly less bitter, words:

The reader has been told much in this case about the personal interest of Mr. Weisman and his daughter, and very little about the personal interests on the other side. They are not inconsequential. Church and state would not be such a difficult subject if religion were, as the Court apparently thinks it to be, some purely personal avocation that can be indulged entirely in secret, like pornography, in the privacy of one’s room…

I didn’t say they weren’t bitter – just that they were slightly less so than before.

Religious men and women of almost all denominations have felt it necessary to acknowledge and beseech the blessing of God as a people, and not just as individuals, because they believe in the “protection of divine Providence,” as the Declaration of Independence put it, not just for individuals but for societies… One can believe in the effectiveness of such public worship, or one can deprecate and deride it. But the longstanding American tradition of prayer at official ceremonies displays with unmistakable clarity that the Establishment Clause does not forbid the government to accommodate it…

I must add one final observation: The Founders of our Republic knew the fearsome potential of sectarian religious belief to generate civil dissension and civil strife. And they also knew that nothing, absolutely nothing, is so inclined to foster among religious believers of various faiths a toleration – no, an affection – for one another than voluntarily joining in prayer together, to the God whom they all worship and seek. Needless to say, no one should be compelled to do that, but it is a shame to deprive our public culture of the opportunity, and indeed the encouragement, for people to do it voluntarily… To deprive our society of that important unifying mechanism, in order to spare the nonbeliever what seems to me the minimal inconvenience of standing or even sitting in respectful nonparticipation, is as senseless in policy as it is unsupported in law.

And with that, we move on.

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Engel v. Vitale (1962)

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Abington v. Schempp (1963)

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Wallace v. Jaffree (1985)

The Court today demonstrates the irrelevance of Lemon by essentially ignoring it, and the interment of that case may be the one happy byproduct of the Court’s otherwise lamentable decision. Unfortunately, however, the Court has replaced Lemon with its psycho-coercion test, which suffers the double disability of having no roots whatever in our people’s historic practice, and being as infinitely expandable as the reasons for psychotherapy itself…

The Court today demonstrates the irrelevance of Lemon by essentially ignoring it, and the interment of that case may be the one happy byproduct of the Court’s otherwise lamentable decision. Unfortunately, however, the Court has replaced Lemon with its psycho-coercion test, which suffers the double disability of having no roots whatever in our people’s historic practice, and being as infinitely expandable as the reasons for psychotherapy itself… In a few days, Oklahoma will

In a few days, Oklahoma will

Of course, lower courts generally defer to decisions from higher courts – that is, after all, the whole idea – and the 10th will no doubt follow the lead of the Supreme Court if they think the case before them is comparable to something previously decided. But if there are critical differences in the details – and there are almost always critical differences in the details – things might easily go the other way.

Of course, lower courts generally defer to decisions from higher courts – that is, after all, the whole idea – and the 10th will no doubt follow the lead of the Supreme Court if they think the case before them is comparable to something previously decided. But if there are critical differences in the details – and there are almost always critical differences in the details – things might easily go the other way.  Haskell County, Oklahoma, had a Ten Commandments monument on their Courthouse lawn, along with several pieces honoring military veterans of various wars. James Green, a local resident, believed the monument violated the separation of church and state. With the help of the ACLU, he sued to have the monument removed.

Haskell County, Oklahoma, had a Ten Commandments monument on their Courthouse lawn, along with several pieces honoring military veterans of various wars. James Green, a local resident, believed the monument violated the separation of church and state. With the help of the ACLU, he sued to have the monument removed. Needless to say, Oklahoma’s efforts are very much of the latter sort. Only quite recently have proponents begun trying to pretend they want anything other than to be ‘King of the Religious Mountain’ with this issue.

Needless to say, Oklahoma’s efforts are very much of the latter sort. Only quite recently have proponents begun trying to pretend they want anything other than to be ‘King of the Religious Mountain’ with this issue.  In about a week, Oklahoma will

In about a week, Oklahoma will  It’s difficult to say which has historically done the greater damage – a government that oppresses religion or a government that supports it. The first tends to end very badly for temporal authority; the latter tends to undermine the faith so favored.

It’s difficult to say which has historically done the greater damage – a government that oppresses religion or a government that supports it. The first tends to end very badly for temporal authority; the latter tends to undermine the faith so favored.  The Alabama Justice lost his position over his refusal to remove the monument. In Tennessee the issue bounced around a bit until the county sheriff agreed to relocate the Commandments from the lobby to his office – still government property, but less ‘public,’ I suppose.

The Alabama Justice lost his position over his refusal to remove the monument. In Tennessee the issue bounced around a bit until the county sheriff agreed to relocate the Commandments from the lobby to his office – still government property, but less ‘public,’ I suppose.  The district court didn’t get past the first question. There was no secular legislative purpose, so bang – you lose. Thanks for playing, Kentucky – sucks to suck.

The district court didn’t get past the first question. There was no secular legislative purpose, so bang – you lose. Thanks for playing, Kentucky – sucks to suck.  The Ten Commandments monument itself incorporated traditional American iconography – an eagle grasping the American flag and an eye inside of a pyramid – as well as two Stars of David and the superimposed Greek letters Chi and Rho, which represent Christ.

The Ten Commandments monument itself incorporated traditional American iconography – an eagle grasping the American flag and an eye inside of a pyramid – as well as two Stars of David and the superimposed Greek letters Chi and Rho, which represent Christ.

No team teaching. No mixed activities. One wonders if perhaps eye contact with anyone wearing an angel pin was discouraged. Remedial instruction could only take place in rooms bereft of religious symbols or imagery, despite the fact that students had been surrounded by sectarian materials the entire day leading up to these lessons.

No team teaching. No mixed activities. One wonders if perhaps eye contact with anyone wearing an angel pin was discouraged. Remedial instruction could only take place in rooms bereft of religious symbols or imagery, despite the fact that students had been surrounded by sectarian materials the entire day leading up to these lessons.

Notice that the argument is as much about professionalism and practicality as it is the finer points of constitutional law:

Notice that the argument is as much about professionalism and practicality as it is the finer points of constitutional law: Justice Souter wrote a fascinating dissent, which several of the other justices joined. His argument is less pragmatic and more big picture. I particularly like this part:

Justice Souter wrote a fascinating dissent, which several of the other justices joined. His argument is less pragmatic and more big picture. I particularly like this part: Beginning in the 1980s, the “wall of separation” between church and state stopped getting higher. The Court’s application of the First Amendment to public schooling became somewhat more sympathetic to people of faith.

Beginning in the 1980s, the “wall of separation” between church and state stopped getting higher. The Court’s application of the First Amendment to public schooling became somewhat more sympathetic to people of faith.