With President-Elect Trump’s selection of Betsy DeVos as Executioner of Public Education, talk of vouchers and their variations are once again filling the crispy winter air. If you’re not already following and reading the #OklaEd Trinity, you should begin by seeing what OKEducation Truths, Fourth Generation Teacher, and A View From The Edge have been saying on the subject.

Actually, Miller (A View From The Edge) has been on a bit of a roll on this topic lately. I may add unnecessary sentences just so I can embed additional links without them seeming forced.

How did I do?

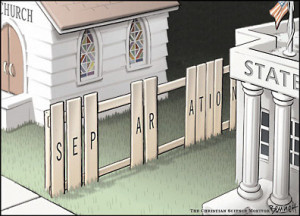

As to yours truly, I’m working my way through Supreme Court cases related to “separation of church and state” as it impacts public education. Most of these involved prayer or religious instruction, although I’d hoped to get into some of the more interesting stuff like the Amish pulling their kids out of school after 8th grade or “After School Satan Clubs.”

As to yours truly, I’m working my way through Supreme Court cases related to “separation of church and state” as it impacts public education. Most of these involved prayer or religious instruction, although I’d hoped to get into some of the more interesting stuff like the Amish pulling their kids out of school after 8th grade or “After School Satan Clubs.”

Yes, really. It’s fascinating stuff.

As part of that, I became absorbed by Zelmer v. Simmons-Harris (2002) – a case which seemed to come up repeatedly when researching vouchers. The Court declared an Ohio program which included vouchers did NOT violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, making lots of #edreform groups and big money types very happy.

Here’s the basic reasoning that allows a voucher program potentially benefiting religious institutions to nonetheless remain constitutional:

First, the goal is secular. Sectarian schools may benefit, or more kids go to religious schools as a result, but promoting quality education for all kids is a valid government function and religiously neutral in and of itself.

Second, the vouchers can’t be designed to favor religious schools or reward parents for choosing them. Even with more “choice,” public options should remain less burdensome than private alternatives.

Third, it’s the parents making the choice – not the government. This is critical. The vouchers (tangible or not) go from the state to the parent, who then makes the decision where or how to utilize them.

In legal terms, this is comparable to a government employee receiving a paycheck and choosing to tithe or donate to a sectarian cause. That’s why voucher supporters are so devout in their rhetoric about money “belonging to parents.” That framing is critical to the constitutionality of the system.

There are problems with this blurring of public and private funds, and it slights the foundational “social contract” which allows civilization to exist. But those aren’t constitutional arguments. In terms of separation of church and state, the Supremes have decided that this whole “parent choice” thing is key.

There are, however, several critical differences between Ohio’s program and anything I’ve seen proposed in Oklahoma so far.

First, Cleveland schools were an absolute disaster by any measure, and decades of pouring extensive resources into efforts to improve them had failed. This is the exact opposite of Oklahoma’s approach – take decent schools and starve them into submission so you can declare them incompetent and justify taking away the remaining resources.

Second, Ohio vouchers were part of a larger, heavily-funded series of educational efforts and innovations which included a variety of “community schools” and “magnet schools” (all part of the public school system) as well as additional funding for after-school tutoring and other forms of support for students who wished to remain in their traditional local public school. Oklahoma has a few token alternatives along these lines, but nothing like what Ohio was doing, and with such limited funding as to allow no real comparison.

Second, Ohio vouchers were part of a larger, heavily-funded series of educational efforts and innovations which included a variety of “community schools” and “magnet schools” (all part of the public school system) as well as additional funding for after-school tutoring and other forms of support for students who wished to remain in their traditional local public school. Oklahoma has a few token alternatives along these lines, but nothing like what Ohio was doing, and with such limited funding as to allow no real comparison.

Third, schools participating in Ohio’s voucher programs were not allowed to pick and choose who they’d accept. Admission policies were regulated by legislation. All involved institutions were required to meet the same basic requirements as public schools, including state assessments. The program was specifically designed to serve low-income and low-performing students, not screen them out. It mandated student diversity, so that participating schools had to reflect rather than deflect the communities around them.

Finally, Ohio put a tight cap on how much parents could be required to pay over and above the amount covered by the state, so that middle and lower income families could actually participate. Oklahoma’s proposals to date seem designed to subsidize those already likely to send their kids to private schools, effectively screening out the sorts of students those private school parents are trying to get their immaculately achromatic darlings away from.

Taken together, it leaves me wondering if any version of vouchers or ESAs which Oklahoma is likely to pass could withstand similar constitutional scrutiny. Then again, daring the courts to overturn them is a point of pride with OK Legis. They love playing legal “chicken” with the third branch, whatever the extensive – and quite literal – costs to the rest of us.

Since Zelmer, there have been several other significant voucher cases decided at various levels. I hope to write about some of them at greater length, but for now… a few highlights.

Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn (2011) – United States Supreme Court

Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn (2011) – United States Supreme Court

A group of Arizona taxpayers filed a lawsuit challenging tax credits given to individuals or organizations who donated to “school tuition organizations” (see “Oklahoma Equal Opportunity Education Scholarship”). The Court held that the plaintiffs lacked standing, and thus couldn’t sue. The connection between state-level budget decisions and their possible impact on any one taxpayer, the Court explained, was too tenuous to establish specific individual harm.

However sweeping the constitutional issues in play, courts generally avoid taking cases based on theoretical damages or larger principles. They want to know if there’s a victim – in part or in whole. If not, they usually won’t act.

So that complicates things.

The Court also acknowledged the State’s argument that the program was intended to save money in the long run, thus actually providing a benefit to taxpayers. Whether it actually worked out that way was not immediately relevant, since the lawsuit was founded on potential outcomes to begin with. Your Rube Goldberg forecast vs. mine, as it were.

LaRue v. Colorado Board of Education (2016) – Colorado Supreme Court

LaRue v. Colorado Board of Education (2016) – Colorado Supreme Court

Colorado’s “school choice” program violated the constitution of the State of Nevada by giving public school money to religious institutions. This one is being appealed to the Supreme Court, some say with hopes the Court will negate or weaken the Blaine Amendment in many state constitutions. I don’t know if that’s a real possibility, but it would be… unfortunate.

Blaine aside, this case has all sorts of fun little quirks I hope to explore soon.

Citizens for Strong Schools v. Florida State Board of Education (2016) – 2nd Judicial Court of Florida

Citizens for Strong Schools v. Florida State Board of Education (2016) – 2nd Judicial Court of Florida

Parents complained that the state was diverting money to voucher programs at the expense of public education. State standards and assessments, furthermore, were constantly-moving-but-high-stakes targets, and legislation repeatedly punished schools via unfunded mandates.

Tell me this sounds familiar.

Florida argued that educators with packed classrooms in high poverty areas simply needed to be more efficient. They spotlighted a smattering of special needs kids finding success through vouchers so that anyone opposed to general implementation must hate handicapped kids.

The judge acknowledged some problems in the system, but didn’t find a violation of the Florida constitution. The case is currently being appealed.

Meredith v. Daniels (2013) – Indiana Supreme Court

Meredith v. Daniels (2013) – Indiana Supreme Court

The Court determined that Indiana’s “Choice Scholarship” Program (vouchers) did not violate the state constitution, but took care to clarify in their written opinion that their ruling should not be misconstrued as validating the effectiveness or appropriateness of this legislation.

Louisiana Federation of Teachers v. State of Louisiana (2013) – Louisiana Supreme Court

Louisiana Federation of Teachers v. State of Louisiana (2013) – Louisiana Supreme Court

The Court determined that the “Louisiana Scholarship Program” violated the state’s own school funding formula and was thus unconstitutional. The Louisiana State Legislature got around this by passing a budget the next session which funded the program outside of that formula.

This is a solution I’ve had proposed to me off-the-record several times by legislators looking for palatable compromise. It strikes me as a distinction without a difference. In a time of ever-changing budgets, how we label which money at what stage is mere semantics. Bureaucratic sophistry.

Still, it does allow a thin façade of principled concern, so keep your eyes open for something like this from OKC.

Lopez v. Schwartz (2016) – Nevada Supreme Court

Lopez v. Schwartz (2016) – Nevada Supreme Court

Nevada’s Education Savings Account (ESA) program violates the constitution of the State of Nevada by taking money out of public education and using it for something other than public schools. In this case, that means funding private schools, including religious schools.

Nevada’s ESA system sounds VERY much like what’s been proposed in Oklahoma repeatedly. This is hardly a surprise, since state legislators take their cue from the same fiscal overlords who hand them the same pre-written legislation but have them write their own names at the top in big brown crayon so they feel like they’ve participated in some way.

The Court did NOT base their decision on any “church and state” problems with the program, but with the specifics of Nevada law which require public education money to be spent on public education. However self-evident that seems like it should be, Oklahoma law may not read the same. I’ll be looking into this further.

Duncan v. State of New Hampshire (2014) – New Hampshire Supreme Court…

Duncan v. State of New Hampshire (2014) – New Hampshire Supreme Court…

In 2012, New Hampshire passed legislation allowing businesses to receive tax credits for donations to “scholarship organizations,” who would in turn establish scholarships for students attending religious schools. (Refer again to the “Oklahoma Equal Opportunity Education Scholarship” and the note above about state legislation coming from the same few suzerains.)

This system allows the state to essentially pay for private schooling through means indirect enough to avoid constitutional challenge. It also frees up religious schools from having to deal with questions of diversity, equity, etc., since they’re not receiving funds directly from the state.

The trial court which first heard the case determined the tax credit program violated the state constitution by allowing public money to be “granted or applied for the use of the schools or institutions of any religious sect or denomination.” The New Hampshire Supreme Court heard the case on appeal and determined that the state taxpayers who brought the suit lacked standing to sue – as in Winn, individual citizens couldn’t demonstrate they were being specifically and directly harmed by the program.

Outcome-wise, that means this case counts as a victory for “school choice.” In reality, it was lost on a subjective, and someone questionable, judgement call regarding the plaintiff’s standing.

Summary

The First Amendment “separation of church and state” argument has limited traction in voucher arguments at this point. It’s not without potential, especially if a state program is set up with substantially fewer public options receiving less funding, but it’s an uphill climb.

State constitutions containing a Blaine Amendment – like, say… Oklahoma’s – offer somewhat stouter potential resistance to lopsided “school choice” legislation. The bar is a bit higher if the state has to establish they’re funding public schools sufficiently and separately from whatever they wish to contribute to their church of choice via state purse strings.

State constitutions containing a Blaine Amendment – like, say… Oklahoma’s – offer somewhat stouter potential resistance to lopsided “school choice” legislation. The bar is a bit higher if the state has to establish they’re funding public schools sufficiently and separately from whatever they wish to contribute to their church of choice via state purse strings.

Finally, state constitutional guarantees regarding funding and support for common ed may be the most foundational source of resistance to any legislation further depleting public ed in service of elite demographics.

Public Education Advocates might keep in mind that the goal is not to quash genuine choice or belittle alternative routes to a well-rounded education. Our priority, I respectfully suggest, is to guarantee all students legitimate access to reasonably high-quality school experience, as part of what it means to be a civilized people – as part of the fundamental social contract that allows peace, prosperity, and progress to exist.

We don’t need others to suffer for us to prosper, or for other pedagogical roads to be closed for ours to remain open and well-maintained. We’re just asking that our kids not be further marginalized and our teachers blamed for not being able to overcome problems far larger than a good lesson plan or a clever district program. We’re trying to remind Oklahoma and its leadership not only of the “rules,” but of why those “rules” – and the ideals behind them – were such a good idea to begin with.

RELATED LINK: The Blasphemy of Vouchers (from Dad Gone Wild)

RELATED LINK: Who Really Benefits From Vouchers And Choice? (from Dad Gone Wild)

RELATED LINK: Top 10 Reasons School Choice Is No Choice (from Gadfly On The Wall Blog)

RELATED LINK: The Essential Selfishness Of School Choice (from Gadfly On The Wall Blog)

RELATED LINK: In Current Form, ESA Proposal Would Widen Inequality (from Oklahoma Policy Institute)

We’ve been looking at Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the case most often cited when I’m researching vouchers and their constitutionality.

We’ve been looking at Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the case most often cited when I’m researching vouchers and their constitutionality.  Here’s a fun little game. Go to

Here’s a fun little game. Go to

As discussed

As discussed

This is where I wonder if the lack of actual

This is where I wonder if the lack of actual  Ohio’s program is constitutional because of all of the non-religious alternatives promoted by the state. If parental choice means a majority of kids end up in religious schools, that’s fine – as long as it’s the result of true choice. That means a variety of accessible options, both religious and non, public and private.

Ohio’s program is constitutional because of all of the non-religious alternatives promoted by the state. If parental choice means a majority of kids end up in religious schools, that’s fine – as long as it’s the result of true choice. That means a variety of accessible options, both religious and non, public and private.

This addresses the second prong of the “

This addresses the second prong of the “

The Oklahoma GOP has for some time now held unchecked control of both the State Legislature and the Governor’s chair. Voters have handed them the keys, a 12-pack of Keystone, and encouraged them to have their way with the state. You’ve no doubt noticed the resulting prosperity trickling down all around you.

The Oklahoma GOP has for some time now held unchecked control of both the State Legislature and the Governor’s chair. Voters have handed them the keys, a 12-pack of Keystone, and encouraged them to have their way with the state. You’ve no doubt noticed the resulting prosperity trickling down all around you.

Actually, this being Oklahoma, I should clarify further. “Are vouchers an effective way to provide a better education for a greater variety of students in a fiscally realistic way?” That’s how they’re promoted ‘round these parts, but I’m not at all convinced that’s the actual goal. (See earlier disclaimer about the humble guy with a blog.)

Actually, this being Oklahoma, I should clarify further. “Are vouchers an effective way to provide a better education for a greater variety of students in a fiscally realistic way?” That’s how they’re promoted ‘round these parts, but I’m not at all convinced that’s the actual goal. (See earlier disclaimer about the humble guy with a blog.)

But you can’t legislate community buy-in, and you can’t mandate teacher satisfaction or require people to stay in the profession. The public wouldn’t pass bonds to pay for stuff, and district school boards wouldn’t make hard choices about cuts. Add school-board drama, conflicts over school closings and program cuts, and the ever-looming issue of racial equity, and despite many good people mostly pursuing what they thought was right, it just… they couldn’t…

But you can’t legislate community buy-in, and you can’t mandate teacher satisfaction or require people to stay in the profession. The public wouldn’t pass bonds to pay for stuff, and district school boards wouldn’t make hard choices about cuts. Add school-board drama, conflicts over school closings and program cuts, and the ever-looming issue of racial equity, and despite many good people mostly pursuing what they thought was right, it just… they couldn’t…