I wrote recently about the ‘urban legends’ of American History – the colorful stories which tend to root in significant events. Even factually flawed, these myths proffer illumination beyond the events themselves through their framing – or even their distortion – of the mere facts of a happening.

I wrote recently about the ‘urban legends’ of American History – the colorful stories which tend to root in significant events. Even factually flawed, these myths proffer illumination beyond the events themselves through their framing – or even their distortion – of the mere facts of a happening.

Sometimes history is reshaped to reflect cultural priorities, other times to give a little extra ‘oomph’ to an important moment. Sometimes the distortion is malicious, or self-serving. Sometimes we just get it wrong.

“Historical Fiction” is a different creature. These tales are both written and read with the overt understanding that they are not necessarily precise in terms of actual objective happening, or at least not defensibly so. The goal is rather to bring flesh and soul to lost people and events in order to capture engaging truths by moving beyond the available facts. It can be powerful, enlightening, controversial, or stirring. Or, sometimes, it just sucks.

What a concept – breathing life into the dusty remnants of the past in order to commune with them more personally. And what vanity, what hubris, to even try! But then, reaching for elusive truths – for those essential intangibles – is what fiction does best, isn’t it?

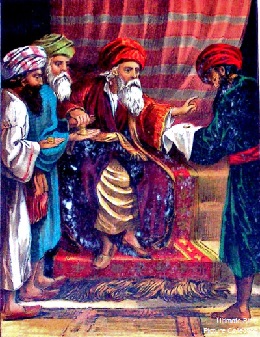

By way of example, here’s a short story with which some of you may be familiar:

A man, going into another country, called his own servants, and delivered unto them his goods. And unto one he gave five talents, to another two, to another one; to each according to his several ability; and he went on his journey.

Straightway he that received the five talents went and traded with them, and made other five talents. In like manner he also that received the two gained other two. But he that received the one went away and digged in the earth, and hid his lord’s money.

Now after a long time the lord of those servants cometh, and maketh a reckoning with them.

And he that received the five talents came and brought other five talents, saying, Lord, thou deliveredst unto me five talents: lo, I have gained other five talents. His lord said unto him, Well done, good and faithful servant: thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will set thee over many things; enter thou into the joy of thy lord.

And he also that received the two talents came and said, Lord, thou deliveredst unto me two talents: lo, I have gained other two talents. His lord said unto him, Well done, good and faithful servant: thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will set thee over many things; enter thou into the joy of thy lord.

And he also that had received the one talent came and said, Lord, I knew thee that thou art a hard man, reaping where thou didst not sow, and gathering where thou didst not scatter; and I was afraid, and went away and hid thy talent in the earth: lo, thou hast thine own.

But his lord answered and said unto him, Thou wicked and slothful servant, thou knewest that I reap where I sowed not, and gather where I did not scatter; thou oughtest therefore to have put my money to the bankers, and at my coming I should have received back mine own with interest. Take ye away therefore the talent from him, and give it unto him that hath the ten talents.

For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not, even that which he hath shall be taken away. And cast ye out the unprofitable servant into the outer darkness: there shall be the weeping and the gnashing of teeth.

I didn’t actually write this one (I don’t even own the copyright on it), but I do recognize that it points to a type of truth above its own details, and beyond investment strategies or commentary on a particular type of caste system. The person telling the story is trying to bring some connection to his listeners – to allow them in some small way to walk in a reality beyond their immediate grasp.

That’s what good fiction often does.

But, you may argue, that’s not exactly “historical fiction.” You’ve deceived us with your clever titles and slick wordplay! Fair enough. It’s just that the lines can be a tad fuzzy.

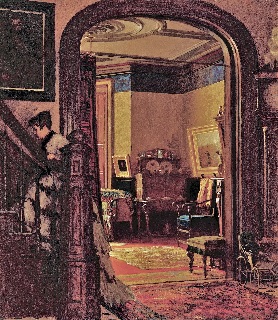

Here’s a classic from Kate Chopin circa 1894:

The Story of an Hour

Knowing that Mrs. Mallard was afflicted with a heart trouble, great care was taken to break to her as gently as possible the news of her husband’s death.

It was her sister Josephine who told her, in broken sentences; veiled hints that revealed in half concealing. Her husband’s friend Richards was there, too, near her. It was he who had been in the newspaper office when intelligence of the railroad disaster was received, with Brently Mallard’s name leading the list of “killed.” He had only taken the time to assure himself of its truth by a second telegram, and had hastened to forestall any less careful, less tender friend in bearing the sad message.

She did not hear the story as many women have heard the same, with a paralyzed inability to accept its significance. She wept at once, with sudden, wild abandonment, in her sister’s arms. When the storm of grief had spent itself she went away to her room alone. She would have no one follow her.

There stood, facing the open window, a comfortable, roomy armchair. Into this she sank, pressed down by a physical exhaustion that haunted her body and seemed to reach into her soul. She could see in the open square before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life. The delicious breath of rain was in the air. In the street below a peddler was crying his wares. The notes of a distant song which some one was singing reached her faintly, and countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves.

There were patches of blue sky showing here and there through the clouds that had met and piled one above the other in the west facing her window. She sat with her head thrown back upon the cushion of the chair, quite motionless, except when a sob came up into her throat and shook her, as a child who has cried itself to sleep continues to sob in its dreams.

She was young, with a fair, calm face, whose lines bespoke repression and even a certain strength. But now there was a dull stare in her eyes, whose gaze was fixed away off yonder on one of those patches of blue sky. It was not a glance of reflection, but rather indicated a suspension of intelligent thought. There was something coming to her and she was waiting for it, fearfully. What was it? She did not know; it was too subtle and elusive to name. But she felt it, creeping out of the sky, reaching toward her through the sounds, the scents, the color that filled the air.

Now her bosom rose and fell tumultuously. She was beginning to recognize this thing that was approaching to possess her, and she was striving to beat it back with her will–as powerless as her two white slender hands would have been. When she abandoned herself a little whispered word escaped her slightly parted lips. She said it over and over under hte breath: “free, free, free!” The vacant stare and the look of terror that had followed it went from her eyes. They stayed keen and bright. Her pulses beat fast, and the coursing blood warmed and relaxed every inch of her body.

She did not stop to ask if it were or were not a monstrous joy that held her. A clear and exalted perception enabled her to dismiss the suggestion as trivial. She knew that she would weep again when she saw the kind, tender hands folded in death; the face that had never looked save with love upon her, fixed and gray and dead. But she saw beyond that bitter moment a long procession of years to come that would belong to her absolutely. And she opened and spread her arms out to them in welcome.

There would be no one to live for during those coming years; she would live for herself. There would be no powerful will bending hers in that blind persistence with which men and women believe they have a right to impose a private will upon a fellow-creature. A kind intention or a cruel intention made the act seem no less a crime as she looked upon it in that brief moment of illumination.

And yet she had loved him–sometimes. Often she had not. What did it matter! What could love, the unsolved mystery, count for in the face of this possession of self-assertion which she suddenly recognized as the strongest impulse of her being!

“Free! Body and soul free!” she kept whispering.

Josephine was kneeling before the closed door with her lips to the keyhold, imploring for admission. “Louise, open the door! I beg; open the door–you will make yourself ill. What are you doing, Louise? For heaven’s sake open the door.”

“Go away. I am not making myself ill.” No; she was drinking in a very elixir of life through that open window. Her fancy was running riot along those days ahead of her. Spring days, and summer days, and all sorts of days that would be her own. She breathed a quick prayer that life might be long. It was only yesterday she had thought with a shudder that life might be long.

She arose at length and opened the door to her sister’s importunities. There was a feverish triumph in her eyes, and she carried herself unwittingly like a goddess of Victory. She clasped her sister’s waist, and together they descended the stairs. Richards stood waiting for them at the bottom.

Someone was opening the front door with a latchkey. It was Brently Mallard who entered, a little travel-stained, composedly carrying his grip-sack and umbrella. He had been far from the scene of the accident, and did not even know there had been one. He stood amazed at Josephine’s piercing cry; at Richards’ quick motion to screen him from the view of his wife.

When the doctors came they said she had died of heart disease–of the joy that kills.

Fiction, yes. Truth? Chopin thought so. She was quite the fan of killing off female protagonists and blaming patriarchy. But is it “historical fiction”?

Mr. & Mrs. Mallard are both entirely fictional, and the exact train accident described is unverifiable. On the other hand, upper middle class women of late 19th century America did often have stairs, and doors, and tumultuous bosoms. The ‘truth’ captured here is not unique to a particular time and place, but it was a specific feature of this time and place. It was also – not uncoincidentally – more or less Kate Chopin’s real life time and place.

Mr. & Mrs. Mallard are both entirely fictional, and the exact train accident described is unverifiable. On the other hand, upper middle class women of late 19th century America did often have stairs, and doors, and tumultuous bosoms. The ‘truth’ captured here is not unique to a particular time and place, but it was a specific feature of this time and place. It was also – not uncoincidentally – more or less Kate Chopin’s real life time and place.

Lest you find Chopin too caliginous to make the point, let me share a very different short story from 1949 that is – as far as I know – entirely fictional, and yet… so very true. I have absolutely no right to reproduce it here:

After You, My Dear Alphonse (Shirley Jackson)

Mrs. Wilson was just taking the gingerbread out of the oven when she heard Johnny outside talking to someone.

“Johnny,” she called, “you’re late. Come in and get your lunch.”

“Just a minute, Mother,” Johnny said. “After you, my dear Alphonse.”

“After you, my dear Alphonse,” another voice said.

“No, after you, my dear Alphonse,” Johnny said.

Mrs. Wilson opened the door. “Johnny,” she said, “you come in this minute and get your lunch. You can play after you’ve eaten.”

Johnny came in after her, slowly. “Mother,” he said, “I brought Boyd home for lunch with me.

“Boyd?” Mrs. Wilson thought for a moment. “I don’t believe I’ve met Boyd. Bring him in, dear, since you’ve invited him. Lunch is ready.”

“Boyd!” Johnny yelled. “Hey, Boyd, come on.

“I’m coming. Just got to unload this stuff.”

“Well, hurry, or my mother’ll be sore.”

“Johnny, that’s not very polite to either your friend or your mother,” Mrs. Wilson said. “Come sit down, Boyd.”

As she turned to show Boyd where to sit, she saw he was a Negro boy, smaller than Johnny but about the same age. His arms were loaded with split kindling wood. “Where’ll I put this stuff, Johnny?” he asked.

Mrs. Wilson turned to Johnny. “Johnny,” she said, “what is that wood?”

“Dead Japanese,” Johnny said mildly. “We stand them in the ground and run over them with tanks.”

“How do you do, Mrs. Wilson?” Boyd said.

“How do you do, Boyd? You shouldn’t let Johnny make you carry all that wood. Sit down now and eat lunch, both of you.

“Why shouldn’t he carry the wood, Mother? It’s his wood. We got it at his place.”

“Johnny,” Mrs. Wilson said, “go on and eat your lunch.”

“Sure,” Johnny said. He held out the dish of scrambled eggs to Boyd. “After you, my dear Alphonse.”

“After you, my dear Alphonse,” Boyd said. “After you, my dear Alphonse,” Johnny said. They began to giggle.

“Are you hungry, Boyd?” Mrs. Wilson asked.

“Yes, Mrs. Wilson.”

“Well, don’t you let Johnny stop you. He always fusses about eating, so you just see that you get a good lunch. There’s plenty of food here for you to have all you want.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Wilson.”

“Come on, Alphonse,” Johnny said. He pushed half the scrambled eggs on to Boyd’s plate. Boyd watched while Mrs. Wilson put a dish of stewed tomatoes beside his plate.

“Boyd don’t eat tomatoes, do you, Boyd?” Johnny said.

“Doesn’t eat tomatoes, Johnny. And just because you don’t like them, don’t say that about Boyd. Boyd will eat anything.”

“Bet he won’t,” Johnny said, attacking his scrambled eggs.

“Boyd wants to grow up and be a big strong man so he can work hard,” Mrs. Wilson said. “I’ll bet Boyd’s father eats stewed tomatoes.”

“My father eats anything he wants to,” Boyd said.

“So does mine,” Johnny said. “Sometimes he doesn’t eat hardly anything. He’s a little guy, though. Wouldn’t hurt a flea.”

“Mine’s a little guy, too,” Boyd said.

“I’ll bet he’s strong, though,” Mrs. Wilson said. She hesitated. “Does he . . . work?”

“Sure,” Johnny said. “Boyd’s father works in a factory.”

“There, you see?” Mrs. Wilson said. “And he certainly has to be strong to do that—all that lifting and carrying at a factory.”

“Boyd’s father doesn’t have to,” Johnny said. “He’s a foreman.”

Mrs. Wilson felt defeated. “What does your mother do, Boyd?”

“My mother?” Boyd was surprised. “She takes care of us kids.”

“Oh. She doesn’t work, then?”

“Why should she?” Johnny said through a mouthful of eggs. “You don’t work.”

“You really don’t want any stewed tomatoes, Boyd?”

“No, thank you, Mrs. Wilson,” Boyd said.

“No, thank you, Mrs. Wilson, no, thank you, Mrs. Wilson, no, thank you, Mrs. Wilson,” Johnny said. “Boyd’s sister’s going to work, though. She’s going to be a teacher.”

“That’s a very fine attitude for her to have, Boyd.” Mrs. Wilson restrained an impulse to pat Boyd on the head. “I imagine you’re all very proud of her?”

“I guess so,” Boyd said.

“What about all your other brothers and sisters? I guess all of you want to make just as much of yourselves as you can.

“There’s only me and Jean,” Boyd said. “I don’t know yet what I want to be when I grow up.

“We’re going to be tank drivers, Boyd and me,” Johnny said. “Zoom.” Mrs. Wilson caught Boyd’s glass of milk as Johnny’s napkin ring, suddenly transformed into a tank, plowed heavily across the table.

“Look, Johnny,” Boyd said. “Here’s a foxhole. I’m shooting at you.”

Mrs. Wilson, with the speed born of long experience, took the gingerbread off the shelf and placed it carefully between the tank and the foxhole.

“Now eat as much as you want to, Boyd,” she said. “I want to see you get filled up.”

“Boyd eats a lot, but not as much as I do,” Johnny said. “I’m bigger than he is.”

“You’re not much bigger,” Boyd said. “I can beat you running.”

Mrs. Wilson took a deep breath. “Boyd,” she said. Both boys turned to her.

“Boyd, Johnny has some suits that are a little too small for him, and a winter coat. It’s not new, of course, but there’s lots of wear in it still. And I have a few dresses that your mother or sister could probably use. Your mother can make them over into lots of things for all of you, and I’d be very happy to give them to you. Suppose before you leave I make up a big bundle and then you and Johnny can take it over to your mother right away…”

Her voice trailed off as she saw Boyd’s puzzled expression. “But I have plenty of clothes, thank you,” he said. “And I don’t think my mother knows how to sew very well, and anyway I guess we buy about everything we need. Thank you very much though.”

“We don’t have time to carry that old stuff around, Mother,” Johnny said. “We got to play tanks with the kids today.”

Mrs. Wilson lifted the plate of gingerbread off the table as Boyd was about to take another piece. “There are many little boys like you, Boyd, who would be grateful for the clothes someone was kind enough to give them.”

“Boyd will take them if you want him to, Mother,” Johnny said.

“I didn’t mean to make you mad, Mrs. Wilson,” Boyd said.

“Don’t think I’m angry, Boyd. I’m just disappointed in you, that’s all. Now let’s not say anything more about it.”

She began clearing the plates off the table, and Johnny took Boyd’s hand and pulled him to the door. “‘Bye, Mother,” Johnny said. Boyd stood for a minute, staring at Mrs. Wilson’s back.

“After you, my dear Alphonse,” Johnny said, holding the door open.

“Is your mother still mad?” Mrs. Wilson heard Boyd ask in a low voice.

“I don’t know,” Johnny said. “She’s screwy sometimes.”

“So’s mine,” Boyd said. He hesitated. “After you, my dear Alphonse.”

That’s too much truth to try to explain with facts. It’s too subtle and profound and works on too many different levels to cram into objective reality. Like Chopin’s tale above, its truth is founded in a particular time and place, but points to something more universal.

Unfortunately.

But when we speak of “historical fiction” we usually mean something a little heavier on the “historical” – more Killer Angels than The Awakening. I can’t wait to read whatever I have to say about THOSE! Next time.

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part I – Historical Myths

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part II – The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part IV – What’s Your Story?

Related Post: Useful Fictions, Part V – “Historical Fiction,” Proper

And he also that had received the one talent came and said, Lord, I knew thee that thou art a hard man, reaping where thou didst not sow, and gathering where thou didst not scatter; and I was afraid, and went away and hid thy talent in the earth: lo, thou hast thine own.

And he also that had received the one talent came and said, Lord, I knew thee that thou art a hard man, reaping where thou didst not sow, and gathering where thou didst not scatter; and I was afraid, and went away and hid thy talent in the earth: lo, thou hast thine own. There stood, facing the open window, a comfortable, roomy armchair. Into this she sank, pressed down by a physical exhaustion that haunted her body and seemed to reach into her soul. She could see in the open square before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life. The delicious breath of rain was in the air. In the street below a peddler was crying his wares. The notes of a distant song which some one was singing reached her faintly, and countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves.

There stood, facing the open window, a comfortable, roomy armchair. Into this she sank, pressed down by a physical exhaustion that haunted her body and seemed to reach into her soul. She could see in the open square before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life. The delicious breath of rain was in the air. In the street below a peddler was crying his wares. The notes of a distant song which some one was singing reached her faintly, and countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves. “That’s a very fine attitude for her to have, Boyd.” Mrs. Wilson restrained an impulse to pat Boyd on the head. “I imagine you’re all very proud of her?”

“That’s a very fine attitude for her to have, Boyd.” Mrs. Wilson restrained an impulse to pat Boyd on the head. “I imagine you’re all very proud of her?” A turtle and a rabbit are having a race on some pretense or other. The race begins, and the rabbit leaves the turtle far behind, as you would expect. The turtle just keeps right on moving as best he can, though, and after a time the rabbit gets lazy, or cocky, or both, and takes a lil’ nap – which is irrational in these circumstances but sets up the moral of the story.

A turtle and a rabbit are having a race on some pretense or other. The race begins, and the rabbit leaves the turtle far behind, as you would expect. The turtle just keeps right on moving as best he can, though, and after a time the rabbit gets lazy, or cocky, or both, and takes a lil’ nap – which is irrational in these circumstances but sets up the moral of the story. The rabbit is the cockiest and cruelest of the animals, and bullies the turtle into a race. The turtle has little choice, and after trying to dissuade the rabbit of the idea, they “agree” to test themselves the following morning. Just to keep things interesting, the rabbit adds a last-minute wager – the winner of the race will kill, cook, and eat the loser.

The rabbit is the cockiest and cruelest of the animals, and bullies the turtle into a race. The turtle has little choice, and after trying to dissuade the rabbit of the idea, they “agree” to test themselves the following morning. Just to keep things interesting, the rabbit adds a last-minute wager – the winner of the race will kill, cook, and eat the loser. Not all snakes are dangerous, for example, and a few may be quite helpful in some ways, but learning to tell hundreds of them apart, quickly, and in various situations, is time, labor, and brain space intensive. If I’m right, nothing happens; if I’m wrong, I could die – painfully.

Not all snakes are dangerous, for example, and a few may be quite helpful in some ways, but learning to tell hundreds of them apart, quickly, and in various situations, is time, labor, and brain space intensive. If I’m right, nothing happens; if I’m wrong, I could die – painfully. Ella’s agency and that of her ilk didn’t completely disappear, but it certainly evolved. Consider the Little Mermaid – who in both the Grimm and Disney versions of the story defies her father, entwines herself with the male of another species (or race), and makes a deal with dark forces to do so. She trades her voice – literally, which should absolutely horrify even the mildest feminist – for a shot at first base with the savior prince.

Ella’s agency and that of her ilk didn’t completely disappear, but it certainly evolved. Consider the Little Mermaid – who in both the Grimm and Disney versions of the story defies her father, entwines herself with the male of another species (or race), and makes a deal with dark forces to do so. She trades her voice – literally, which should absolutely horrify even the mildest feminist – for a shot at first base with the savior prince.