Anyone in the world of public education for any length of time knows that we have a tendency to oversimplify things which are more complicated than we care to admit and to complicate things which simply don’t have to be that difficult.

Anyone in the world of public education for any length of time knows that we have a tendency to oversimplify things which are more complicated than we care to admit and to complicate things which simply don’t have to be that difficult.

“It’s such a challenge to find and retain good teachers!”

(We should pay them more.)

“We should talk to the local colleges about their training programs.”

(Yes, and then pay teachers better.)

“I’m thinking of a book study for district administration on what makes an effective educator.”

(Great – I’m in. But you get what you pay for, and…)

“We’re bringing in a consultant. He’s pretty expensive, but I think it will be worth it to improve teacher quality.”

(Yes, or we could use that money to pay our teachers better…)

“Let’s show that TED Talk on how Google runs their home offices. I’m having some of the chairs painted bright colors like in the video and I’m hoping that will change the climate building-wide.”

(OK, but Google also seeks out top talent and then pays them well…)

“We put in all this training and then lose them to the private sector…”

(Which pays them better.)

You get the idea.

But some things are genuinely difficult. Sometimes there are no easy answers – at least not useful ones.

Terrorism is a fun topic that can’t help but enliven any social event. Let’s take a hypothetical nation with a corrupt or marginalized government, high poverty, and limited opportunity, which becomes a “breeding ground” (here’s to loaded language) for terrorism. We’ll call it Scarykillastan.

Terrorism is a fun topic that can’t help but enliven any social event. Let’s take a hypothetical nation with a corrupt or marginalized government, high poverty, and limited opportunity, which becomes a “breeding ground” (here’s to loaded language) for terrorism. We’ll call it Scarykillastan.

For purposes of our example, let’s grossly oversimplify our response options. We can crack down militarily – bombs and soldiers and counterstrikes and whatnot – or we can nation-build – schools and health care and clean water and jobs. As part of this gross oversimplification, let’s assume both options cost roughly the same up front.

If the goal is to reduce terrorism, the only consideration should be which option accomplishes this more effectively. But… is it?

Imagine for a moment that the 1960’s flower-in-the-rifle-barrel thing turns out to be legitimately effective – that if we establish schools and clinics and make sure the locals (including the terrorists) have access to food and clean water, terrorism drops by 90% (remember – hypothetical). On the other hand, if we bomb the hell out of them and their support systems – women, children, and neighboring innocents alike – terrorism drops locally by 75% but pops up in surrounding areas for a net drop of, say… 50%.

How many of us would still demand the latter option over the former? How many of us would still feel on some primal level that the peaceful response is WRONG – that it’s rewarding bad behavior? Coddling backwards mindsets and lifestyles? That it demonstrates weakness and lack of will?

I’m not mocking anyone. It genuinely feels backwards. Some of you will be angry even reading it as a hypothetical example. I’m also not sure things actually work out quite so efficiently in real life, although with this particular example I’ve heard some good arguments that they could. But many of us would argue against the hippie solution even if it repeatedly and demonstrably worked better – for less money, at the cost of fewer lives, and possibly even improving our moral standing in the world.

I’m not mocking anyone. It genuinely feels backwards. Some of you will be angry even reading it as a hypothetical example. I’m also not sure things actually work out quite so efficiently in real life, although with this particular example I’ve heard some good arguments that they could. But many of us would argue against the hippie solution even if it repeatedly and demonstrably worked better – for less money, at the cost of fewer lives, and possibly even improving our moral standing in the world.

Child poverty and health care are another example – elements of a complex and extensive reality which I’m again grossly oversimplifying in hopes of making a point. Currently, there’s an unforgivably high number of minors in the U.S. who lack proper care – healthy meals, medical attention, counseling, mentors, etc. Some end up getting in trouble, going to jail or otherwise dropping out of mainstream society. Others avoid major legal entanglements but never rise above their class or circumstances. A number of them die and leave behind the next generation of mess. And the beat goes on.

Since this is a hypothetical (although the problem itself is very real), we can say with clinical detachment that these people are a huge drain on society. They cost money via emergency rooms, detention facilities, and prisons. They burn through resources when they go to school or use public accommodations, and are more likely to vandalize, pollute, and require attention from police or fire services. They don’t become as economically productive as they could, and often end up on public assistance of various sorts.

It’s frustrating, and expensive.

What if it could be demonstrated with great certainty that spending more on social services, education, health care, etc., leads to lower crime, higher graduation rates, and over time saves millions of local dollars? What if it could be established that taking better care of society’s most marginalized elements pays off in both human and fiscal terms? Just to stretch our hypothetical, let’s throw in some extra care for women, sex ed in every high school, and maybe some affirmative action, and have it all result in better neighborhoods, higher productivity, fewer unwanted pregnancies and STDs, and a reliable surplus in the state coffers. Would we do it?

What if it could be demonstrated with great certainty that spending more on social services, education, health care, etc., leads to lower crime, higher graduation rates, and over time saves millions of local dollars? What if it could be established that taking better care of society’s most marginalized elements pays off in both human and fiscal terms? Just to stretch our hypothetical, let’s throw in some extra care for women, sex ed in every high school, and maybe some affirmative action, and have it all result in better neighborhoods, higher productivity, fewer unwanted pregnancies and STDs, and a reliable surplus in the state coffers. Would we do it?

It sounds like a no brainer – at least in my oversimplified hypothetical. But if it were that binary, that guaranteed, would we do it?

I’m not sure the answer is a universal “YES!” I’m not even confident I could get a majority on board.

Because for many of us, it just feels wrong. Like we’re enabling bad behavior, even if (in our hypothetical) it reduces bad behavior. Like we’re rewarding sloth, even if (in our hypothetical) more people are working and keeping jobs. Like we’re compromising on our values, even if (in our hypothetical) more people are living out our values as a result.

I’ve read and listened to conversations not so different from these in schools over the past few years. Sometimes it starts with experiments in restorative justice in place of traditional discipline, or some sort of cultural diversity training in an effort to reduce suspensions and referrals. Other times it begins with conversations about grading practices, or due dates, or student efficacy, or standards-based something-or-other.

I’ve written about some of these topics before; I’m not exactly a committed reformer when it comes to education policy or trendy solutions. And almost everything about public education is more complicated than social media and expensive presenters would have you believe.

But what if it wasn’t?

What if eliminating grades could be shown to dramatically improve student learning? What if eliminating detentions and suspensions could be shown to drastically reduce discipline problems (not just acknowledgment of those problems, but the actual problems)? What if taking more radical steps towards cultural equity and social justice didn’t create chaos and rolling eyes over talk of safe spaces and microaggressions, but could be repeatedly and objectively shown to improve behavior, and learning, and future success in life, and whatever else we think is important?

What if eliminating grades could be shown to dramatically improve student learning? What if eliminating detentions and suspensions could be shown to drastically reduce discipline problems (not just acknowledgment of those problems, but the actual problems)? What if taking more radical steps towards cultural equity and social justice didn’t create chaos and rolling eyes over talk of safe spaces and microaggressions, but could be repeatedly and objectively shown to improve behavior, and learning, and future success in life, and whatever else we think is important?

Would we enthusiastically begin doing those things?

Do we hesitate because the issues aren’t that simple? Because we’re skeptical as to whether this or that change could possibly have the dramatic impact its proponents claim? Is it because some of it sounds a bit trendy? Or trite? Or just… stupid?

There may be good reasons not to just dive in.

But is it possible that woven into the mix, just behind our carefully couched objections, is a much deeper layer of outrage, or annoyance? A primal demand for a different sort of justice, or vengeance? A vested interest in a sort of moral or cultural hierarchy?

Is it possible that whatever the very real challenges of counter-terrorism, or reducing child poverty, or improving public education, that the proverbial elephant in our subconscious room isn’t effectiveness or cost or validity, but a sense of ideological betrayal? Is there a morally outraged itch of some sort we can’t quite identify but which someone is threatening to stop scratching?

Because, seriously, CAN’T THOSE PEOPLE JUST GET THEIR %#(# TOGETHER AND THEN WE WON’T HAVE A PROBLEM ANYMORE AND WON’T HAVE TO KEEP BRINGING UP ALL THIS STUPID NEW-AGE INANITY?!? Or, more calmly, “Forget the results – can’t they just GET there the WAY we want them to?!”

Because, seriously, CAN’T THOSE PEOPLE JUST GET THEIR %#(# TOGETHER AND THEN WE WON’T HAVE A PROBLEM ANYMORE AND WON’T HAVE TO KEEP BRINGING UP ALL THIS STUPID NEW-AGE INANITY?!? Or, more calmly, “Forget the results – can’t they just GET there the WAY we want them to?!”

You’ve probably thought or felt some variety of this in relation to at least some of these issues. I certainly have.

I’m not arguing for increased aid to Syria or more money for social programs (not here, anyway). I’m certainly not suggesting that more resolution circles or the mass burning of student policy handbooks will loose the Magi-gogical Unicorns to flit alongst your hallways, pooping rainbows of racial unity, well-mannered “grit,” and improved critical thinking skills across the curriculum.

Complicated issues are complicated even when we all think we want the same thing. But certainly the first step for anyone looking to make meaningful improvements or address deep-rooted difficulties should be to check our own motivations and attitudes. Otherwise, we’re in real danger of undermining the very values we claim to be defending, and hurting very real people in the process.

The stories are everywhere.

The stories are everywhere.  No one knows history anymore.

No one knows history anymore. Complete freedom is chaos, and extremely limiting, when everyone has it. Nothing lasting can be accomplished because we’re all too… free – and selfish in our freedom.

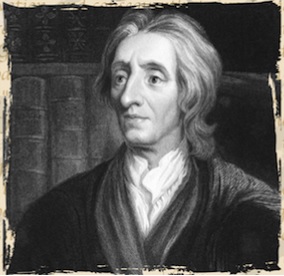

Complete freedom is chaos, and extremely limiting, when everyone has it. Nothing lasting can be accomplished because we’re all too… free – and selfish in our freedom.  John Locke’s version of the “social contract” was similar, but had some important distinctions you might recognize…

John Locke’s version of the “social contract” was similar, but had some important distinctions you might recognize…  For those of you who didn’t go to Sunday School (tsk tsk!), the Old Testament is about taking care of US – the CHOSEN people, the GOOD people. It’s rather harsh for most everyone else – the OTHER, the UNCLEAN.

For those of you who didn’t go to Sunday School (tsk tsk!), the Old Testament is about taking care of US – the CHOSEN people, the GOOD people. It’s rather harsh for most everyone else – the OTHER, the UNCLEAN.  Do we want to settle for compromises and logistics, tweaking via Amendment or reinterpretation from time to time, as we’ve done with our Constitution and (to a less-admitted extent) our scriptures; or do we want to strive for the ideals that are the ENTIRE REASON for either document to exist in the first place?

Do we want to settle for compromises and logistics, tweaking via Amendment or reinterpretation from time to time, as we’ve done with our Constitution and (to a less-admitted extent) our scriptures; or do we want to strive for the ideals that are the ENTIRE REASON for either document to exist in the first place? Except we’re not doing it for them – we never were. Ultimately, it helps each of us when we find a place for all of us. On the whole, it’s good for each of us when we learn to value all of us.

Except we’re not doing it for them – we never were. Ultimately, it helps each of us when we find a place for all of us. On the whole, it’s good for each of us when we learn to value all of us.