{This Post is Recycled – Reworked from a Previous Version and Reposted In It’s Updated Glory}

In Part One, I waxed eloquent about secession and the South’s stated reasons for attempting to leave. Among their many complaints – most of which involved perceived threats to slavery – was the North’s tolerance of those who snuck in and taught slaves stuff.

A little knowledge, it turns out, can be a dangerous thing.

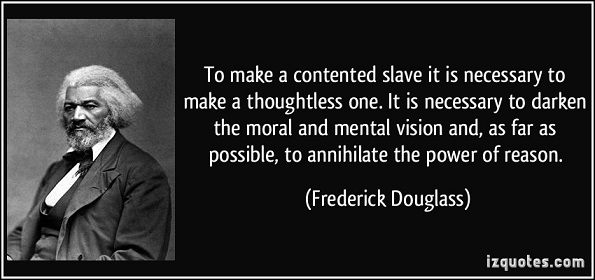

Frederick Douglass, in his first autobiography (1845), describes his epiphany regarding education:

My new mistress proved to be all she appeared when I first met her at the door,—a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings. She had never had a slave under her control previously to myself, and prior to her marriage she had been dependent upon her own industry for a living. She… had been in a good degree preserved from the blighting and dehumanizing effects of slavery…

One thing Douglass’s account shares with those of Solomon Northup, Harriet Jacobs, and others, is their insistence that not all slave-owners were naturally cruel and evil people. They avoid neatly dividing people into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ and instead focus on the system, and its effect on those involved – slave or free, black or white.

Rather than letting a few slaveholders off the moral hook, it puts the rest of us on it. When the problem is bad people, we’re safe because we’re not them. When the problem is something larger, something systemic, which we either ignore or tolerate, we’re no longer absolved.

Very soon after I went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Auld, she very kindly commenced to teach me the A, B, C. After I had learned this, she assisted me in learning to spell words of three or four letters…

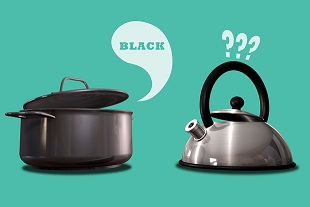

Mr. Auld found out what was going on, and at once forbade Mrs. Auld to instruct me further, telling her, among other things, that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe, to teach a slave to read. To use his own words, further, he said… “A nigger should know nothing but to obey his master—to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world.”

Mr. Auld was no fool. He knew that control – whether of populations or individuals – begins through the information to which they have access. Whoever controls knowledge controls everything else – especially when it comes to maintaining a system based on privilege and inheritance.

Mr. Auld was no fool. He knew that control – whether of populations or individuals – begins through the information to which they have access. Whoever controls knowledge controls everything else – especially when it comes to maintaining a system based on privilege and inheritance.

You know, like the one we pretend we don’t have today.

”Now,” said he, “if you teach that nigger (speaking of myself) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.”

Mr. Auld is at least honest. Rather than claim young Frederick CAN’T learn, the problem is very much that he CAN – and as things stand, that helps no one. Raised expectations are a curse both ways.

These words sank deep into my heart, stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought…

Isn’t that what the best learning does? Challenge everything, and force you to separate the assured from the assumed?

I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty—to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man… From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom. It was just what I wanted, and I got it at a time when I the least expected it…

If your room under the stairs is all you’ve ever known, you may not be happy, but you can hardly fathom more. Once you’ve gone to a museum or zoo, your horizons are forever altered – there are things out there of which you didn’t know. And Hogwarts… still full of limits, but compared to the room under the stairs…?

There’s nothing wrong with learning to be content with what you have, but that’s a choice we can only make if we have some glimpse of the alternatives. Until then, you’re just… stuck.

There’s nothing wrong with learning to be content with what you have, but that’s a choice we can only make if we have some glimpse of the alternatives. Until then, you’re just… stuck.

Douglass started tasting something bigger than he’d known, and for the first time found himself able to give form to his sense of bondage.

I was now about twelve years old, and the thought of being a slave for life began to bear heavily upon my heart. Just about this time, I got hold of a book entitled “The Columbian Orator.” Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book. Among much of other interesting matter, I found in it a dialogue between a master and his slave.

The slave was represented as having run away from his master three times. The dialogue represented the conversation which took place between them, when the slave was retaken the third time. In this dialogue, the whole argument in behalf of slavery was brought forward by the master, all of which was disposed of by the slave. The slave was made to say some very smart as well as impressive things in reply to his master—things which had the desired though unexpected effect; for the conversation resulted in the voluntary emancipation of the slave on the part of the master…

Slavery is bad, and running away was illegal. Talking back to one’s master was dangerous and not to be advised – it was unlikely to lead to your emancipation. All this book lacked to be utterly perverse by the standards of the day were zombies and a gay shower scene. And yet, Douglass discovered benefit in reading this work of subversive fiction.

Douglass connected with a character who was in some ways like himself – not in wise words or holy determination, but in the ways his life sucked, like being a slave. This fictional character, however, was able to demonstrate at least one possible way to endure or even flourish in the ugly, imperfect situation in which he was mired. He resonated far more than an idealized hero-figure of some sort could have, belching platitudes while fighting off the darkness with patriotic pluck.

Douglass connected with a character who was in some ways like himself – not in wise words or holy determination, but in the ways his life sucked, like being a slave. This fictional character, however, was able to demonstrate at least one possible way to endure or even flourish in the ugly, imperfect situation in which he was mired. He resonated far more than an idealized hero-figure of some sort could have, belching platitudes while fighting off the darkness with patriotic pluck.

Douglass became who he was partly because of a banned book.

The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than a band of successful robbers, who had left their homes, and gone to Africa, and stolen us from our homes, and in a strange land reduced us to slavery. I loathed them as being the meanest as well as the most wicked of men.

Here’s the number one reason governments and religions and parents and schools ban whatever they ban. It’s nearly impossible to maintain the illusion you’re doing someone a huge favor by keeping them locked under the staircase once they’ve visited Hogwarts – even by proxy. The power to question is the power to overcome.

As I read and contemplated the subject, behold! that very discontentment which Master Hugh had predicted would follow my learning to read had already come, to torment and sting my soul to unutterable anguish. As I writhed under it, I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing. It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy. It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out.

In moments of agony, I envied my fellow-slaves for their stupidity. I have often wished myself a beast. I preferred the condition of the meanest reptile to my own. Anything, no matter what, to get rid of thinking!

Finally, something our elected representatives could support.

Douglass went on to become one of the most powerful speakers and important writers of the 19th century. He also turned out to be a pretty good American, despite his dissent regarding any number of issues.

Turns out you can do that.

Learning is dangerous, but not to the person doing the learning. It can hurt along the way, but you usually end up better off for it.

Learning is dangerous, but not to the person doing the learning. It can hurt along the way, but you usually end up better off for it.

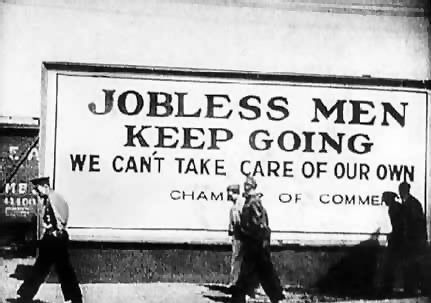

Learning is dangerous to men whose ideas lack sufficient merit or whose systems lack sufficient substance to maintain their influence over people once they have other options.

Schoolhouse Rock intoned in the 1970’s that “It’s great to learn – ‘Cause Knowledge is Power!” A few thousand years before, Jesus of Nazareth had promised his followers that “you will know the truth, and the truth will set your free.” He was speaking most directly of Himself and salvation, but the principle echoes past the specifics.

In a time of strict codes and limited freedom, He offended the churchiest of them with his associations, the liberties he took with the law designed to protect them from damnation, and by suggesting we might not need holy arbiters any longer to find our way.

At the risk of getting preachy, the curtain tore long before Martin Luther nailed his complaints to the door.

Perhaps the Scribes and Pharisees had underlying good intentions, being naturally rooted in the ways of Old Testament law. They grew up under a God who’d kill you for touching His ark, even if it was to prevent it falling to the ground. We’ll cut them some slack.

The Inquisitions and Puritans and Assigners of Scarlet Letters in New Testament times have no such excuse. If their faith is what they claim, it’s a faith based on light and truth and – above all – informed choice. Jesus and Paul may not have had much in common, but there’s no record of either lying or hiding something they didn’t want the world to see. They had enough faith in their message that it could withstand freedom of choice. They didn’t want to capture anyone who didn’t wish to be won.

The Inquisitions and Puritans and Assigners of Scarlet Letters in New Testament times have no such excuse. If their faith is what they claim, it’s a faith based on light and truth and – above all – informed choice. Jesus and Paul may not have had much in common, but there’s no record of either lying or hiding something they didn’t want the world to see. They had enough faith in their message that it could withstand freedom of choice. They didn’t want to capture anyone who didn’t wish to be won.

You don’t make better citizens or better Christians by hiding or prohibiting things you don’t want them to know. You can’t strengthen faith by torturing those who sin. You certainly can’t narrow the gap between young people and American ideals by doing a better job bullsh*tting them.

It’s wrong to even try, of course, but it also just doesn’t work.

Let’s have a little faith in our spiritual ideals, and our foundational values as a nation. Let’s offer enough light and live enough of an example that we can risk letting those we love have a little freedom. If they come back…

Well, you know the rest.

RELATED POST: Secession & Superiority (A Little Knowledge Is A Dangerous Thing, Part One)

RELATED POST: Liar, Liar, Twitterpants on Fire (A Little Knowledge Is A Dangerous Thing, Part Three)

RELATED POST: I’d Rather Be Aquaman

Was Lincoln’s election really such a threat to their way of life? Maybe. Not according to Lincoln, it wasn’t, but the new Republican Party openly advocated for restrictions on slavery – particularly in terms of limiting its expansion. Perhaps that was a debate worth having, in the context of the times.

Was Lincoln’s election really such a threat to their way of life? Maybe. Not according to Lincoln, it wasn’t, but the new Republican Party openly advocated for restrictions on slavery – particularly in terms of limiting its expansion. Perhaps that was a debate worth having, in the context of the times. “We don’t like the thinking prompted by your teachers, your books, your visuals. We don’t appreciate you complicating their worlds or ours by introducing problematic ideas. Ignorance is bliss, buddy – our version of reality is good enough, despite its apparent inability to withstand the slightest scrutiny.”

“We don’t like the thinking prompted by your teachers, your books, your visuals. We don’t appreciate you complicating their worlds or ours by introducing problematic ideas. Ignorance is bliss, buddy – our version of reality is good enough, despite its apparent inability to withstand the slightest scrutiny.”

One of the most bizarre mischaracterizations of history is the idea that in the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth, the Lord made the North free, and just, without prejudice or malice. He saw the North, and declared that it was ‘good’.

One of the most bizarre mischaracterizations of history is the idea that in the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth, the Lord made the North free, and just, without prejudice or malice. He saw the North, and declared that it was ‘good’. In reality, by the dawn of the 19th century there was slavery pretty much everywhere in the United States. More in some places than others, but it was a thing all over. There were abolitionists as well – pretty much everywhere – carrying on about the evil of the peculiar institution and making everyone unhappy.

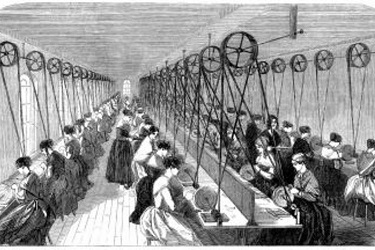

In reality, by the dawn of the 19th century there was slavery pretty much everywhere in the United States. More in some places than others, but it was a thing all over. There were abolitionists as well – pretty much everywhere – carrying on about the evil of the peculiar institution and making everyone unhappy. Besides, they already had an entirely different class of not-quite-people to exploit and dehumanize. In the elite world of historiography, we call them the “Irish.”

Besides, they already had an entirely different class of not-quite-people to exploit and dehumanize. In the elite world of historiography, we call them the “Irish.” The cotton gin, as every middle school history teacher can tell you, made cotton production what we historians call ‘way cray’ more profitable – thus cementing slavery as an ‘essential’ institution for decades past its anticipated life span. Unintended consequences suck.

The cotton gin, as every middle school history teacher can tell you, made cotton production what we historians call ‘way cray’ more profitable – thus cementing slavery as an ‘essential’ institution for decades past its anticipated life span. Unintended consequences suck. Well, obviously the south is full of sinners. Not like us – we’re good people. That’s why we abolished it.

Well, obviously the south is full of sinners. Not like us – we’re good people. That’s why we abolished it. Wages [referring to ‘free’ factory labor in the North] is a cunning device of the devil, for the benefit of tender consciences who would retain all the advantages of the slave system without the expense, trouble, and odium of being slaveholders. (Orestes A. Brownson, 1840)

Wages [referring to ‘free’ factory labor in the North] is a cunning device of the devil, for the benefit of tender consciences who would retain all the advantages of the slave system without the expense, trouble, and odium of being slaveholders. (Orestes A. Brownson, 1840) The plot had more holes than Battlestar Galactica, and nearly as many characters we still can’t quite figure out whether to love or despise. (Say what you like about the Cylons, they at least had moral clarity.)

The plot had more holes than Battlestar Galactica, and nearly as many characters we still can’t quite figure out whether to love or despise. (Say what you like about the Cylons, they at least had moral clarity.)

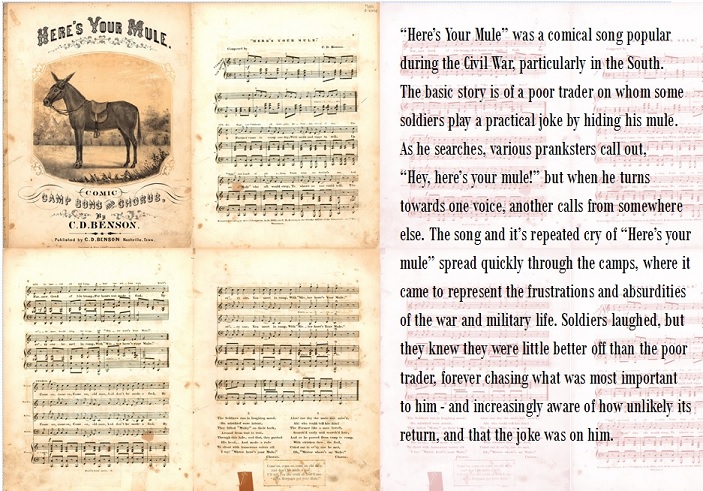

The American Civil War is one of the most written about, discussed, reenacted, and debated events in all of human history. It was important, of course – major battles and nation-changing outcomes and all – but I’m not sure that’s its primary fascination for us.

The American Civil War is one of the most written about, discussed, reenacted, and debated events in all of human history. It was important, of course – major battles and nation-changing outcomes and all – but I’m not sure that’s its primary fascination for us. They’d declared independence together less than a century before and fought the British together – twice. Both extolled the same form of government (even after the South attempted to secede, the ‘nation’ they created for themselves was essentially the same in structure as the one they’d left). They quoted the same Declaration of Independence and revered the same Constitution.

They’d declared independence together less than a century before and fought the British together – twice. Both extolled the same form of government (even after the South attempted to secede, the ‘nation’ they created for themselves was essentially the same in structure as the one they’d left). They quoted the same Declaration of Independence and revered the same Constitution. In every region of the country, the dominant social, political, and economic class was composed almost entirely of straight white educated land-owning males. Most of them looked down on pretty much everyone else.

In every region of the country, the dominant social, political, and economic class was composed almost entirely of straight white educated land-owning males. Most of them looked down on pretty much everyone else.

It’s a mischaracterization, however, to imagine the North was mostly industrialized by 1860. The majority of Northerners lived and worked on small farms or in small businesses, growing food for themselves and their families and perhaps trading or selling surplus for other goods. Most factories were in the North, but most of the North wasn’t factories.

It’s a mischaracterization, however, to imagine the North was mostly industrialized by 1860. The majority of Northerners lived and worked on small farms or in small businesses, growing food for themselves and their families and perhaps trading or selling surplus for other goods. Most factories were in the North, but most of the North wasn’t factories. Southern geography meant agriculture on an entirely different scale. Long growing seasons, flatter lands, different soil – this was God’s way of promoting sugar, tobacco, and most of all, cotton. It was the Elvis of cash crops.

Southern geography meant agriculture on an entirely different scale. Long growing seasons, flatter lands, different soil – this was God’s way of promoting sugar, tobacco, and most of all, cotton. It was the Elvis of cash crops. This will be a problem for the South. That’s more foreshadowing – I hope I don’t ruin the ending for anyone.

This will be a problem for the South. That’s more foreshadowing – I hope I don’t ruin the ending for anyone. Not liking someone, not hiring them, or even not wanting to live next to them, didn’t mean you didn’t have to deal with them at all. The variety of cultures, languages, foods, beliefs, etc., forced a sort of tolerance and accommodation foreign to the South. At the same time, capitalist ideals and an early sort of ‘Social Darwinism’ largely prevented that accommodation from becoming too ‘kumbaya’.

Not liking someone, not hiring them, or even not wanting to live next to them, didn’t mean you didn’t have to deal with them at all. The variety of cultures, languages, foods, beliefs, etc., forced a sort of tolerance and accommodation foreign to the South. At the same time, capitalist ideals and an early sort of ‘Social Darwinism’ largely prevented that accommodation from becoming too ‘kumbaya’.

It is difficult for those of you with the slightest shred of decency to appreciate how the law and politics work. They do not operate according to anything most of us consider reasonable, moral, or even explicable. In the past they didn’t have to (and in some systems today they still don’t). Those affected had little expectation of being fully informed and no real control of the outcome.

It is difficult for those of you with the slightest shred of decency to appreciate how the law and politics work. They do not operate according to anything most of us consider reasonable, moral, or even explicable. In the past they didn’t have to (and in some systems today they still don’t). Those affected had little expectation of being fully informed and no real control of the outcome. And then the South began writing the history of the war and the events which led to it. The war they’d lost. The one fought over a variety of issues, but in which slavery and its continuation were central and essential as defined by the South in the very documents they issued to justify their cause.

And then the South began writing the history of the war and the events which led to it. The war they’d lost. The one fought over a variety of issues, but in which slavery and its continuation were central and essential as defined by the South in the very documents they issued to justify their cause. What’s less tolerable is the fervent hurt and chagrin evidenced by the South’s defenders at the very suggestion that secession had ANYTHING to do with slavery. It’s not that they wish to lay out a reasoned argument, you understand – it’s that they’ve reshaped history and historiography solely through repetition and strong emotion.

What’s less tolerable is the fervent hurt and chagrin evidenced by the South’s defenders at the very suggestion that secession had ANYTHING to do with slavery. It’s not that they wish to lay out a reasoned argument, you understand – it’s that they’ve reshaped history and historiography solely through repetition and strong emotion. My favorite hockey team captain after a tough loss and horrible officiating: “There were some tough calls, but the real problem is that we didn’t take care of business in our own end. We let too many pucks get past us and didn’t take advantage of our opportunities.”

My favorite hockey team captain after a tough loss and horrible officiating: “There were some tough calls, but the real problem is that we didn’t take care of business in our own end. We let too many pucks get past us and didn’t take advantage of our opportunities.”  Of course, if the real issues were states’ rights-ish, that’s not as bad. Federalism is about balance, after all, and if perhaps the South got out of balance, that’s clearly rectified now. If anything, the central government is much stronger than originally intended as a result!

Of course, if the real issues were states’ rights-ish, that’s not as bad. Federalism is about balance, after all, and if perhaps the South got out of balance, that’s clearly rectified now. If anything, the central government is much stronger than originally intended as a result! If our ideals are as flawless and their realizations as consistent throughout our history as current legislation insists, then inequity and suffering are primarily a result of personal or cultural failures. If America is ‘exceptional’ in the way they demand we acknowledge, whatever failures have occurred within it are individual and not national. Potential solutions or cures must, logically, come from the same.

If our ideals are as flawless and their realizations as consistent throughout our history as current legislation insists, then inequity and suffering are primarily a result of personal or cultural failures. If America is ‘exceptional’ in the way they demand we acknowledge, whatever failures have occurred within it are individual and not national. Potential solutions or cures must, logically, come from the same. I’ll close with a little Bible talkin’, since that seems to be such a motivator for those pushing a better whitewashing for our lil’uns. Whatever we may disagree on, I wholeheartedly concur that we’ve lost much in our upbringing if we feel the need to run from the wisdom found in

I’ll close with a little Bible talkin’, since that seems to be such a motivator for those pushing a better whitewashing for our lil’uns. Whatever we may disagree on, I wholeheartedly concur that we’ve lost much in our upbringing if we feel the need to run from the wisdom found in