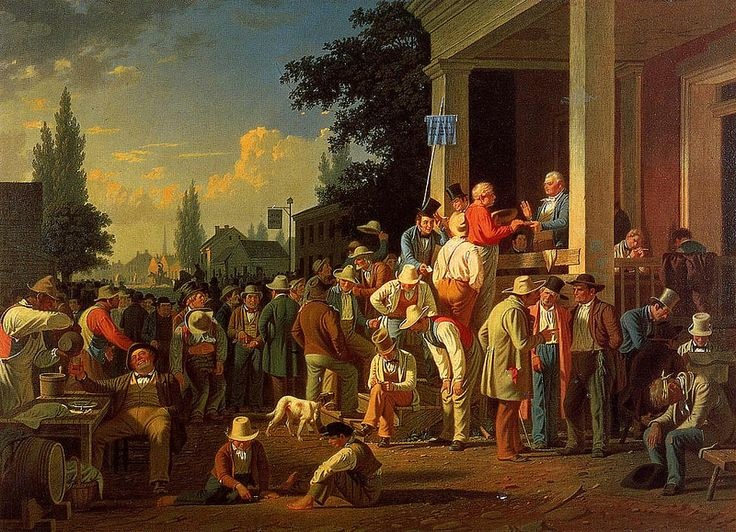

When Andrew Jackson was elected President in 1828, it was an unabashed victory for ‘the common man’.

After six presidencies of consciously ‘elite gentlemen’ – rich, white, educated males – Jackson was a game changer. Sure, he was a white guy – but he grew up all kinda poor, and lacked a formal education until early adulthood.

The expansion of voting rights and other civic validity which allowed such a thing, and which continued to expand during and after his presidency, is even named after him: “Jacksonian Democracy.” It’s a trend of which we’re generally proud two centuries later. Maybe the “all men” created equal in 1776 were a fairly limited bunch, but over time we’ve stretched that to cover quite a variety of colors and socio-economic statuses. Heck, we even let girls vote now – that’s getting serious.

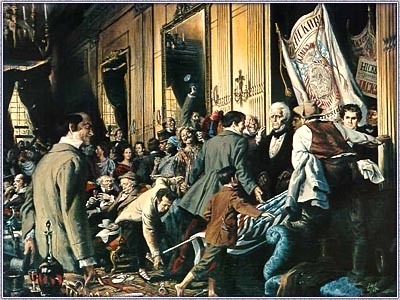

To celebrate this ‘victory of the common man’, Jackson broke with the restrictive traditions of his predecessors and threw open his inaugural celebration at the White House to all comers. It wasn’t HIS victory, after all – it was THEIR victory. Why not let THEM celebrate it as fully as anyone?

To celebrate this ‘victory of the common man’, Jackson broke with the restrictive traditions of his predecessors and threw open his inaugural celebration at the White House to all comers. It wasn’t HIS victory, after all – it was THEIR victory. Why not let THEM celebrate it as fully as anyone?

In return, the ‘common man’ trashed the place.

Celebrants stood on and broke furniture, wandered into the private, personal rooms and made souvenirs of the bathroom fixtures and any nice undergarments they discovered in the bedrooms. When the front entrances grew congested, they tromped through the muddy gardens and came in the windows, further destroying the rugs and furniture and generally wreaking havoc.

Jackson bailed almost immediately. The help finally had to lure out the unwashed masses with bowls of alcoholic beverages and trays of deserts, which were hurriedly filled and rushed to the peripheries of the grounds in an effort to Pied Piper the common man the hell out of the White House.

Jackson’s entire Presidency was spotted with such tensions. In his determination to defend and assist the ‘common man’, he pushed through legislation that crippled the economy. In order to open up homesteads for the ‘little people’, he oversaw Indian Removal. His fervent defense of his not-quite-divorced-from-her-first-husband wife led to innumerable conflicts before he took office, and his transferred outrage in defense of similarly soiled Peggy Eaton a few years later crippled his cabinet throughout his time in power.

That’s the difficulty in defending the ‘common man’. They’re dirty, and they do stupid things. One might argue that’s why they’re ‘common’.

It’s not merely an income issue; economic equity is no easy task, but it’s at least tangible. Social capital is more difficult. In a pinch, I can give you money – but I can’t give you decorum. I can buy you a house – but I can’t stop you from leaving trash in the yard or easily explain how to use the space properly.

The sociology of it all is rather tangled and unsatisfying.

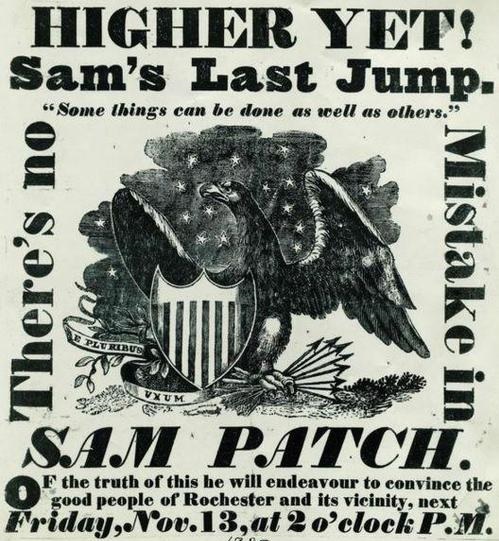

Sam Patch jumped off of cliffs near waterfalls, off of the topmost masts of ships, and from other daunting heights – often into the narrowest of survivable apertures, disciplining body and breathing precisely to allow him to emerge unharmed.

Sam Patch jumped off of cliffs near waterfalls, off of the topmost masts of ships, and from other daunting heights – often into the narrowest of survivable apertures, disciplining body and breathing precisely to allow him to emerge unharmed.

It was noble, in a way. Kinda cool, and so counter to the carefully crafted ‘nature experiences’ built by the well-to-do. Each leap was intensely primitive compared to precisely arranged visitations of the finest majestic sights available only to the elite. Even the rhetoric – “Some things can be done as well as others,” or “There’s no mistake in Sam Patch” – was marvelously stark compared to the noble blithering which filled the finest bourgeois journals.

Patch was a bacon cheeseburger to the artisanal foraged essence of kimchi of his day. But he was a bacon cheeseburger with a tall draft beer. Or seven. And greasy. Dripping on the shirt. And falling apart halfway through. And leaving the wrapper in your yard.

It’s easy two centuries later to belittle Timothy Crane and his precious little recreation area with its froo-froo bridge. He charged for… nature! If he really cared about art, if he really valued beauty, he’d make it available to all – without cost or restriction!

Others did just that. Idealists in some parts of the north opened their parks and benches, their landscaped gardens and artistic efforts to all, just as Nature and Nature’s God had done before them. In return, the common man trashed the place, vandalizing, urinating, and harassing the better elements until they no longer frequented such places.

What gives a man value? Is it his ability to earn a certain income? Behave a certain way? Contribute something useful? How far beyond the Golden Rule can or should society go in its expectations of all peoples, whatever their status or background?

How do we draw a clear distinction between the sort of ‘behaving decently’ we might reasonably ask of all well-intentioned people, and the limiting mores of middle or upper class privilege, with its own rules and codes – many designed over the decades for the sole purpose of separating the cream from the whey?

When we speak of universal rights, and of the value of people, it shouldn’t be so difficult to untether those rights and that underlying value from expected levels of education or behavior. When we move past the fundamentals, though, and drift into questions of equity, opportunity, social standing, lifestyles, and a wider range of values, it’s much murkier. What do people deserve? And from whom?

I may dig the Ramones, but I’d never invite them to dinner among proper company. I love the reckless abandon of some of my students, but I’m not sure I’d risk putting them in charge of anything potentially life-altering for myself or those around them.

I may dig the Ramones, but I’d never invite them to dinner among proper company. I love the reckless abandon of some of my students, but I’m not sure I’d risk putting them in charge of anything potentially life-altering for myself or those around them.

I admire Sam Patch and his giant wet middle finger to the system, but I recognize even while singing his praises that he wasn’t merely rejecting a loftier lifestyle – he was completely unqualified and incapable of living out one had it been handed to him. There’s too much correlation between his rejection of the system and his inability to function within it. Jackson gloried in the baseness of the common man – he seemed to equate it with a sort of primitive purity, which strikes me as… intentionally naive.

Or maybe Jackson’s exaggerated faith in the little guy was merely something with which he fed his own power struggle, and maintained his own outrage. Maybe it just got him from where he was to where he was determined to go. When Philadelphia gave him a beautiful white horse in 1833, Jackson named it ‘Sam Patch’.

I appreciate the sentiment, but should I pass, and you get a gerbil or something, please don’t honor me in this specific way.

I don’t have a satisfying conclusion or moral to the tale. Patch resonates with me, but I’m still not sure I’ve managed to explain to myself just why. I suspect it’s that, while I find his dysfunction offensive and his self-destruction unnecessary, it’s still much easier to cheer for him than for the manufactured pretense and gilded desperation of men like Crane. Maybe it’s as simple as that.

RELATED POST: Sam Patch (Part One)

RELATED POST: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part One – This Land

RELATED POST: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part Two – Chosen People

However stunning the surroundings, these were necessarily utilitarian times. You didn’t come to Pawtucket if things in your life had gone according to plan; the remnants who found work in the mills were either without a male head of house, or stuck with one of little use. You came because you needed work, and Pawtucket was happy to oblige.

However stunning the surroundings, these were necessarily utilitarian times. You didn’t come to Pawtucket if things in your life had gone according to plan; the remnants who found work in the mills were either without a male head of house, or stuck with one of little use. You came because you needed work, and Pawtucket was happy to oblige.  Besides offsetting his costs, the fee was designed to screen out ne’er-do-wells. The park was designed for the ‘right’ kind of people, who were far more likely to both appreciate and take care of the area. Free admission, he feared, would allow the dregs and drunkards to spoil the space. Their inability to pay was indicative of far more than income level – it was a tag of behavior and education.

Besides offsetting his costs, the fee was designed to screen out ne’er-do-wells. The park was designed for the ‘right’ kind of people, who were far more likely to both appreciate and take care of the area. Free admission, he feared, would allow the dregs and drunkards to spoil the space. Their inability to pay was indicative of far more than income level – it was a tag of behavior and education.  On November 13, 1829, Sam made his last jump. Something went horribly wrong. It may have been the drinking or a related difficulty, but descriptions from those witnessing the event suggest he died in mid-air from something internal. His body positioning gave way and he fell limply for at least half of the 125 feet he spent in the air, striking the water with an impact which would have been fatal had he still been alive.

On November 13, 1829, Sam made his last jump. Something went horribly wrong. It may have been the drinking or a related difficulty, but descriptions from those witnessing the event suggest he died in mid-air from something internal. His body positioning gave way and he fell limply for at least half of the 125 feet he spent in the air, striking the water with an impact which would have been fatal had he still been alive.