Cases don’t just magically appear in the Supreme Court. Except in rare circumstances, they begin as local disputes, sometimes working their way up through District Courts. By the time a case comes before the highest court in the land, it’s often been going on in some form for several years.

Cases don’t just magically appear in the Supreme Court. Except in rare circumstances, they begin as local disputes, sometimes working their way up through District Courts. By the time a case comes before the highest court in the land, it’s often been going on in some form for several years.

The Court nevertheless chose to hear School District of Abington Township v. Schempp (1963) only one short year after its decision in Engel v. Vitale (1962). Their decision to do so suggests they saw something in this case distinct from the issues a year before. Otherwise, they’d have remanded it to the lower courts for reconsideration in light of their ruling in Engel.

The case is remembered for the Court’s 8-1 ruling that government-sponsored Bible reading or prayer in public schools is unconstitutional. It violates the First Amendment as applied to the states through the Fourteenth.

Other than the focus on ‘Bible reading’ instead of prayer (in this case it was often the Lord’s Prayer rather than the very general incantation at issue in Engel), it would seem to be a repeat of the previous case. It does have a few interesting little features, however, which make it worth separate consideration here.

The case began in the late 1950’s when Edward Schempp, his wife, and two of his kids who went Pennsylvania public schools, argued that their religious rights (they were Unitarians) were being violated by a state law that required public schools to begin each school day with a reading of at least 10 verses from the Bible.

Pennsylvania tried to deflect the issue by changing the law to allow students to be excused with a written request from a parent, but the case nevertheless moved forward.

Sometimes the Supreme Court will combine similar cases to be heard together. This was what happened in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), for example – while the story of Linda Brown still remains the ‘face’ of the case, there were actually four other cases, all pushed by the NAACP, packaged together with Brown and technically considered and decided at the same time.

Schempp’s case was combined with a case from Baltimore, Murray v. Curlett. While Abington is the one we most often remember and discuss, it was Murray – as in “Madelyn Murray O’Hair” – who made the biggest personal ripple at the time.

Ms. O’Hair was America’s most prominent and outspoken atheist of the 20th Century. For several generations after Abington/Murray was decided, she was cited and demonized as the woman who removed God – or at least prayer – from public schools.

Whatever the spiritual ramifications of her actions, this simply wasn’t true. She fought prayer and Bible-reading in public schools, to be sure, but the prayer issue had already been decided by the time her case made it to the Supreme Court, and the Bible-reading issue would have turned out the way it did with or without her.

That doesn’t mean she’s not burning in eternal damnation even as we speak, but history is history. I’m just saying.

That doesn’t mean she’s not burning in eternal damnation even as we speak, but history is history. I’m just saying.

The second memorable feature of this case, besides the decision itself, is that for the first time the Court developed a sort of ‘test’ to be used in subsequent situations to determine whether or not the Establishment Clause was being violated.

From the majority opinion, written by Justice Tom C. Clark:

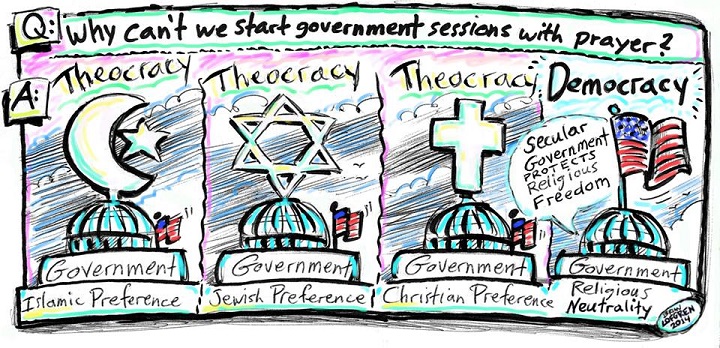

The wholesome “neutrality” of which this Court’s cases speak thus stems from a recognition of the teachings of history that powerful sects or groups might bring about a fusion of governmental and religious functions or a concert or dependency of one upon the other to the end that official support of the State or Federal Government would be placed behind the tenets of one or of all orthodoxies. This the Establishment Clause prohibits.

And a further reason for neutrality is found in the Free Exercise Clause, which recognizes the value of religious training, teaching and observance and, more particularly, the right of every person to freely choose his own course with reference thereto, free of any compulsion from the state. This the Free Exercise Clause guarantees.

Thus, as we have seen, the two clauses may overlap. As we have indicated, the Establishment Clause has been directly considered by this Court eight times in the past score of years and, with only one Justice dissenting on the point, it has consistently held that the clause withdrew all legislative power respecting religious belief or the expression thereof.

The test may be stated as follows: what are the purpose and the primary effect of the enactment? If either is the advancement or inhibition of religion, then the enactment exceeds the scope of legislative power as circumscribed by the Constitution. That is to say that, to withstand the strictures of the Establishment Clause, there must be a secular legislative purpose and a primary effect that neither advances nor inhibits religion…

The Court would “update” this test less than a decade later in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). The updated version – commonly referred to as the “Lemon Test” – is far better known and still utilized today.

The Court would “update” this test less than a decade later in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). The updated version – commonly referred to as the “Lemon Test” – is far better known and still utilized today.

Justice Clark’s opinion quotes from the record of the initial “trial court” which heard the case to begin with. Better than anything else, it summarizes the reasoning behind the final decision:

The reading of the verses, even without comment, possesses a devotional and religious character and constitutes, in effect, a religious observance. The devotional and religious nature of the morning exercises is made all the more apparent by the fact that the Bible reading is followed immediately by a recital in unison by the pupils of the Lord’s Prayer.

The fact that some pupils, or, theoretically, all pupils, might be excused from attendance at the exercises does not mitigate the obligatory nature of the ceremony, for . . . Section 1516 . . . unequivocally requires the exercises to be held every school day in every school in the Commonwealth.

The exercises are held in the school buildings, and perforce are conducted by and under the authority of the local school authorities, and during school sessions. Since the statute requires the reading of the “Holy Bible,” a Christian document, the practice . . . prefers the Christian religion. The record demonstrates that it was the intention of . . . the Commonwealth . . . to introduce a religious ceremony into the public schools of the Commonwealth.

Like Justice Black before him, Justice Clark soon launches into a history lesson about the role of faith in our collective past. He cites related cases, some involving schools and others not, before this poignant little line:

The government is neutral, and, while protecting all, it prefers none, and it disparages none.

There’s more history and lots of quoting from other cases, then this:

We repeat and again reaffirm that neither a State nor the Federal Government can constitutionally force a person “to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.” Neither can constitutionally pass laws or impose requirements which aid all religions as against nonbelievers, and neither can aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.

A bit later we get to that ‘test’ discussed above, then more reasoning and quoting. It’s actually a bit tedious as majority opinions go – no offense to the late Justice Clark.

This bit caught my attention:

Further, it is no defense to urge that the religious practices here may be relatively minor encroachments on the First Amendment. The breach of neutrality that is today a trickling stream may all too soon become a raging torrent and, in the words of Madison, “it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties.”

Pages of legal reasoning and precedence, then suddenly “a trickling stream may all too soon become a raging torrent.” If only Clark had discovered his penchant for drama a few dozen pages earlier.

It is insisted that, unless these religious exercises are permitted, a “religion of secularism” is established in the schools.

Oooh! This sounds interesting. It’s essentially the same accusation made against public schools in Oklahoma by our very own 21st century representatives a couple times a year.

Oooh! This sounds interesting. It’s essentially the same accusation made against public schools in Oklahoma by our very own 21st century representatives a couple times a year.

We agree, of course, that the State may not establish a “religion of secularism” in the sense of affirmatively opposing or showing hostility to religion, thus “preferring those who believe in no religion over those who do believe.” … We do not agree, however, that this decision in any sense has that effect.

In addition, it might well be said that one’s education is not complete without a study of comparative religion or the history of religion and its relationship to the advancement of civilization. It certainly may be said that the Bible is worthy of study for its literary and historic qualities. Nothing we have said here indicates that such study of the Bible or of religion, when presented objectively as part of a secular program of education, may not be effected consistently with the First Amendment.

I’ve cited this bit more than once when talking to teachers about religious content in school. You can’t read much great literature or analyze many great American speeches without a foundation of Biblical literacy. Reform movements or wars, individuals or cultures – the impact of religion is ubiquitous in our collective past, and to deny it would be to rewrite that history substantially.

But the exercises here do not fall into those categories. They are religious exercises, required by the States in violation of the command of the First Amendment that the Government maintain strict neutrality, neither aiding nor opposing religion.

It sounds so simple, although at least one concurring Justice acknowledged how tricky this could sometimes be in practice. Despite popular perception in the 21st Century, the Court expressed no interest in stifling or limiting religion – it merely refused to make it, or any specific form of it, in any way mandatory.

It would be eight years before another case of note involving public education and the role of faith would reach the Supreme Court. It would produce the best-known ‘test’ for weighing whether or not a particular policy or practice was, in fact, in violation of one of those tricky ‘religion’ clauses.

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Engel v. Vitale (1962)

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Everson v. Board of Education (1947)

RELATED POST: Building A Wall of Separation (Faith & School)

After Everson v. Board of Education (1947), fifteen years passed before the next important ‘religion and public schools’ case made its way to the Supreme Court. Whereas Everson dealt with transportation, Engel v. Vitale (1962) addressed the role of the supernatural in the classroom itself.

After Everson v. Board of Education (1947), fifteen years passed before the next important ‘religion and public schools’ case made its way to the Supreme Court. Whereas Everson dealt with transportation, Engel v. Vitale (1962) addressed the role of the supernatural in the classroom itself.

I can’t wait to hear what Governor Fallin and Preston Doerflinger determine about how much tithe God intends for you to pay, and where it should best be applied. And if you argue against them, you’re part of the godless liberalism pervading our once great nation. Good times!

I can’t wait to hear what Governor Fallin and Preston Doerflinger determine about how much tithe God intends for you to pay, and where it should best be applied. And if you argue against them, you’re part of the godless liberalism pervading our once great nation. Good times! You read somewhere online that Christians are mad about coffee cups. You already despise a certain breed of religious person, and this seems to fit that profile. You and a hundred others you follow rant about those nuts and their damn cup obsession, eventually blaming them for not doing more for the homeless, for trying to run your life and ruin your relationships, and for that one pastor who molested that boy.

You read somewhere online that Christians are mad about coffee cups. You already despise a certain breed of religious person, and this seems to fit that profile. You and a hundred others you follow rant about those nuts and their damn cup obsession, eventually blaming them for not doing more for the homeless, for trying to run your life and ruin your relationships, and for that one pastor who molested that boy.

But knowing the origins of something doesn’t automatically reshape our emotional expectations and ideals. We are not a people known for clinging to our own history, let alone that of the grander human story. Trivia from 2,000 years ago isn’t likely to compel us to give up our caroling, forsake our eggnog, or burn our DVDs of Scrooged, Elf, or the Die Hard Trilogy.

But knowing the origins of something doesn’t automatically reshape our emotional expectations and ideals. We are not a people known for clinging to our own history, let alone that of the grander human story. Trivia from 2,000 years ago isn’t likely to compel us to give up our caroling, forsake our eggnog, or burn our DVDs of Scrooged, Elf, or the Die Hard Trilogy.  But I’d respectfully suggest that the aches and fears some have over the ongoing de-Christing of the season may not be proof they are fascists, or oppressors, or Fox News morning show hosts (except the ones who are). It may simply be that they feel like something special is being taken away from them for reasons they don’t entirely understand.

But I’d respectfully suggest that the aches and fears some have over the ongoing de-Christing of the season may not be proof they are fascists, or oppressors, or Fox News morning show hosts (except the ones who are). It may simply be that they feel like something special is being taken away from them for reasons they don’t entirely understand.  on when you’re cold and expected pizza.

on when you’re cold and expected pizza.  You don’t have to accept others’ perceptions, but your blood pressure might go down a bit if you assumed the less-than-worst of those expressing frustration. Sure, it would be nice if reason and research won the day more often, but how many of us choose a spouse, an outfit, or even a restaurant only after a day in the library and a pro/con spreadsheet? We’re simply not that detached from our own perceptions and experiences.

You don’t have to accept others’ perceptions, but your blood pressure might go down a bit if you assumed the less-than-worst of those expressing frustration. Sure, it would be nice if reason and research won the day more often, but how many of us choose a spouse, an outfit, or even a restaurant only after a day in the library and a pro/con spreadsheet? We’re simply not that detached from our own perceptions and experiences.