Tell Him About The Twinkie, Ray

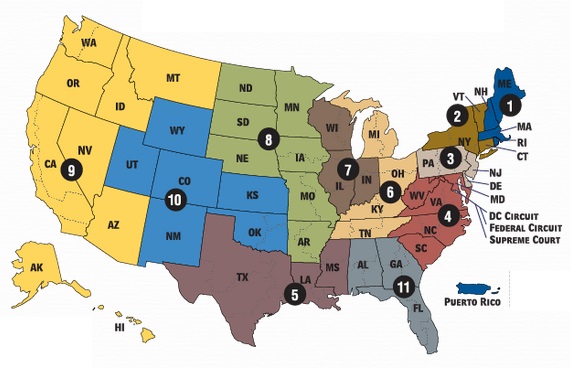

In researching cases for the follow-up to “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases, I came across a case from Tennessee that simply fascinates me, despite being a relatively minor decision in the larger scheme of things. Unable to resist chasing this particular rabbit trail, I posted last time about the basic complaint (fundamentalist parents didn’t like a literature textbook) and the summary dismissal by a federal judge in Eastern Tennessee. The case was appealed to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, however, which is where we pick up today.

I’m simply giddy, aren’t you?

Let’s Phrase That Differently…

Part of the appeal of digging through the written records of this case as it bounced around the courts is that we lack easy access to the specific complaints, the textbook itself (although I’m working on that), and any verbal arguments made in various courts. Those things may be public record in Tennessee or Ohio somewhere, but short of a road trip (“Hey, honey? I know you were looking forward to seeing your parents over the holidays, but I’m super-curious about some obscure court transcripts from 35 years ago, so… can we go the other direction instead?”), all we have are the decisions of various judges.

They’re all looking at the same material; the differences in what’s discussed at each step is a function of the status of the case and what each court wishes to emphasize. For example, we have the 6th Circuit’s complete response to the parents’ appeal. They refused to hear the case (this first time), but neither were they sold on the lower court’s decision to issue a summary judgement in favor of the school district. Why?

In our opinion, as hereinafter pointed out, there were sufficient disputed issues of fact not resolved to make it erroneous for the district court to grant summary judgment. We therefore reverse and remand for the district court to conduct an evidentiary hearing and to adopt findings of fact and conclusions of law.

This is no doubt standard judicial stuff – “It looks to us like judgey judgey, so legal legal legal, etc.” I’d make a poor member of the bench, however, because what I’m hearing is much closer to “Not sure what YOU were thinking, Mr. ‘I-Don’t-Feel-Like-Having-A-Real-Trial’, but this one needs to be heard FOR REAL. You know, if you’re not too busy to BE A FEDERAL JUDGE PROPERLY.”

I’m sure it wasn’t perceived that way, however. That would be silly.

Probably.

Overexposure Is Bad For The Soul

Appellants, who are fundamentalist Christians, brought an action in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee… to enjoin the Board and its administrators from compelling their children to participate in classes which used the Holt primer and to instead permit them to have their own separate reading classes with a different “non-offensive” reading primer. The complaint alleged that the Holt books contained teachings which were contrary to their fundamentalist beliefs and that their religion forbade them from reading such contrary teachings. Appellants emphasized that they were not seeking to ban the Holt books from the schools nor did they object to its use by the rest of the student body.

This is an important distinction. The parents weren’t trying to get their own materials or beliefs injected INTO the curriculum; they were merely trying to allow their own children to opt OUT of the existing materials because they found them offensive. This sets the issue apart from issues like school prayer or creationism, in that they’re not apparently interested in pressuring other children into conforming to their religious druthers. If there were, the case would be far simpler. It might even have justified the way the judge in Tennessee completely blew them off and no-wonder-he’ll-never-reach-the-circuit-courts-like-us.

This is an important distinction. The parents weren’t trying to get their own materials or beliefs injected INTO the curriculum; they were merely trying to allow their own children to opt OUT of the existing materials because they found them offensive. This sets the issue apart from issues like school prayer or creationism, in that they’re not apparently interested in pressuring other children into conforming to their religious druthers. If there were, the case would be far simpler. It might even have justified the way the judge in Tennessee completely blew them off and no-wonder-he’ll-never-reach-the-circuit-courts-like-us.

{A}ppellees submitted an affidavit by appellee Hawkins County School Superintendent Bill Snodgrass in which he defended the decision to use the Holt books. Snodgrass stated his belief that the books were very instructive and attractive and that they substantially enhanced reading skills. He warned that if the appellants were permitted to opt out of the regular reading program and to hold their own alternative classes “teachers would have no control over the management, they could not possibly teach skills in sequential order and the teaching-learning process would become completely unmanageable chaos.”

The “appellees” are school officials (roughly comparable to the “defendants” in a criminal trial). Superintendent Snodgrass made the first argument that would have come to my mind if asked to create a separate “non-offensive” lesson every time I used a story which didn’t overtly promote fundamentalist Christianity. “Are you kidding? I’m not doubling my work load in order to cater to a few, you know… wing nuts!”

Wisely, he didn’t put it that way. He started with what a swell book this particular publication truly is (although I desperately hope he didn’t actually call it “instructive and attractive”), then transitioned into “what they’re asking for isn’t practical.” The problem is that the school’s defense sounds rather whiney this way, and perhaps a tad melodramatic. “B-b-b-but… we couldn’t teach the SKILLS in SEQUENTIAL ORDER and it would all just end up… we mean… CHAOS!”

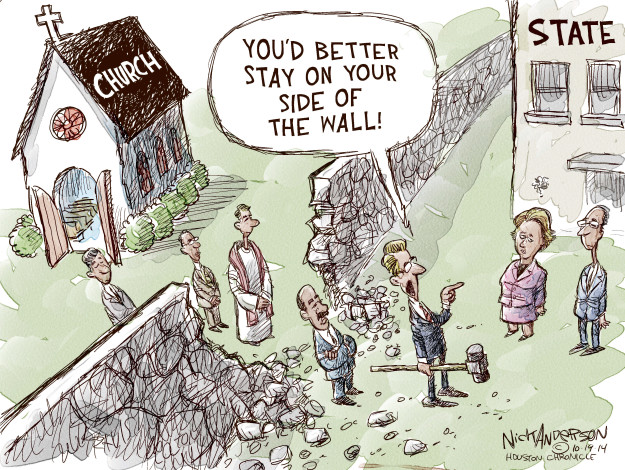

The district added that any attempt to create a second curriculum to accommodate a specific religious group would run them into trouble with the Establishment Clause. This is a bit like throwing a seatbelt violation onto a speeding ticket, but given the consistency with which the Supreme Court had been condemning perceived establishment violations in the decades leading up to Mozert, it was probably worth a shot.

The (Offensive?) Nature of Public Education

While the general idea of the Superintendent’s complaint is no doubt spot on, I have to wonder why his team didn’t lead with what to me is the much more palatable argument. “We WANT our kids to be exposed to a variety of ideas and beliefs. We’re not telling them what to believe; we’re trying to help them understand how other people think and feel – the essential foundation of all civilization. While the mechanics of grammar and structure may be the foundation of reading instruction, empathy is the heart and soul of all good literature. Teaching them that they don’t have to even be in the room anytime someone around them veers into non-fundamentalism isn’t freedom of religion – it’s freedom from thought, challenge, or diversity. It’s a violation of our ethical and professional obligation to prepare them to function in the real world – socially, professionally, and politically.”

While the general idea of the Superintendent’s complaint is no doubt spot on, I have to wonder why his team didn’t lead with what to me is the much more palatable argument. “We WANT our kids to be exposed to a variety of ideas and beliefs. We’re not telling them what to believe; we’re trying to help them understand how other people think and feel – the essential foundation of all civilization. While the mechanics of grammar and structure may be the foundation of reading instruction, empathy is the heart and soul of all good literature. Teaching them that they don’t have to even be in the room anytime someone around them veers into non-fundamentalism isn’t freedom of religion – it’s freedom from thought, challenge, or diversity. It’s a violation of our ethical and professional obligation to prepare them to function in the real world – socially, professionally, and politically.”

Or something along those lines. And the Court got there on their own, eventually… sort of. I just find it an odd choice – right up there with the parents initially insisting they didn’t want their kids corrupted by deceptive creatures like Anne Frank, because that doesn’t conjure up unpleasant implications or anything.

Speaking of which, it sounds like the appellants (the parents who didn’t like the textbook) at some point revised their list of offending materials a bit. Not sure if this was before or after the case bumped up to the Sixth, but notice how differently this reads than the version we read about in Eastern Tennessee:

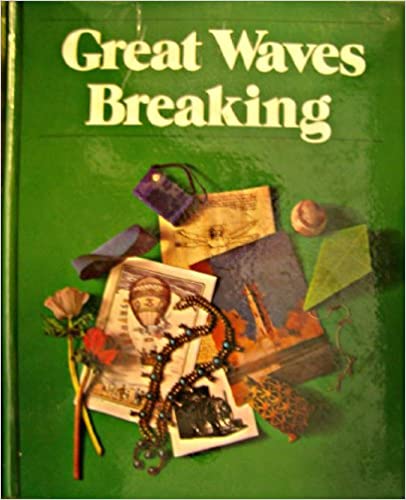

Appellants subsequently filed an amended complaint which more specifically set out their reasons for objecting to the Holt books. They claimed that the books were offensive to their religious beliefs because: (1) they teach witchcraft in violation of Biblical precepts against such teaching; (2) they teach that certain values, held to be absolute by appellants, are relative depending upon the situation; (3) they teach that it is proper to be disobedient to parents, despite Biblical precepts to the contrary; (4) they teach that idol worship may be beneficial and that prayer to a horse god may have helped to end World War II, despite the Biblical prohibition against idol worship and belief; (5) they teach that one can achieve salvation simply by having faith in the supernatural without necessarily believing in Jesus; (6) they teach that Jesus needed the help of Jewish scribes to write his story — thus implying that Jesus was illiterate — despite the fact that the Bible says that Jesus was literate and that his story was written by non-Jews; (7) they teach that man evolved from the common ancestors of monkeys in contradiction of the creation story in the Bible; (8) they teach “humanism, . . . one world concepts [and] antinationalism” — values which are contrary to those possessed by appellants.

While I’m still skeptical about the degree to which short stories in a middle school primer truly pushed little people into worshipping horse gods, this list has the significant benefit of not sounding completely insane. One might even begin to wonder if perhaps the touchy-feely, one-gluten-free-world mojo so popular with academic types in the late 1970s might have infiltrated the editorial choices of those most in a position to influence tiny brains. At what point have we raced well past “everyone is different” and ended up lost somewhere between “meat is murder” and “vote Bernie or we all perish”?

It’s Not A Bug; It’s A Feature

By way of driving their point home, those sneaky fundies had somehow secured a copy of the Teacher’s Edition of the textbook in question – which, for those of you outside the world of public education, is akin to nabbing the Ark of the Covenant from Indiana Jones or remotely hacking celebrity cell phones in order to post their dirty selfies online. The Court explains:

By way of driving their point home, those sneaky fundies had somehow secured a copy of the Teacher’s Edition of the textbook in question – which, for those of you outside the world of public education, is akin to nabbing the Ark of the Covenant from Indiana Jones or remotely hacking celebrity cell phones in order to post their dirty selfies online. The Court explains:

Appellants… cited an essay written by Thomas J. Murphy, Holt’s Senior Vice President for its school book division, which was published in the teacher’s edition of one of the Holt books. In this essay, Murphy noted that school reading programs involve more than simply the teaching of reading skills but also the shaping of students’ ethical values. He contrasted the values of the reading books used previously in the schools with the new Holt books. The former, he indicated, “emphasized a Judeo-Christian values system in a most direct way” while the latter emphasized the need for students “to have a sense of themselves as participants in a national and world community; to understand and to be mindful of the richness of our diversity.”

Appellants alleged that these statements show that the Holt authors rejected the traditional Judeo-Christian values and sought to teach contrary values. Appellants also cited several examples in the books themselves which they claim support their contention, including readings which discuss, without disapproval, Chinese, Islamic and Buddhist philosophy.

Reading isn’t just about the mechanics, the publisher’s Hippie-in-Chief contends – it’s about “shaping students’ ethical values” (and no doubt unblocking their chakras and promoting free love and such). How? By helping students see themselves as part of a larger world in which not everyone is like them.

What the district should have been proclaiming as its strongest defense, the fundamentalists were mic-dropping as irrefutable proof of the overt offense which set them off in the first place.

We’re going to come back to this. It is, in my mind, the most salient issue of the entire case – and the one connecting it in a very real way to major changes in how our nation is choosing to define itself a generation later.

First, however, we should wrap up the 6th Circuit’s decision.

Remanding and Demanding

Summary judgment may be granted only if there is no genuine issue with respect to the material facts of the case… This issue must be resolved on remand by the district court with appropriate findings of fact and conclusions of law.

{T}he state can permissibly impose a burden on an individual’s free exercise rights if the state has a compelling justification for doing so. Appellees insist that their interest in teaching reading to the elementary school students under their charge is just such a compelling interest which would justify the burden imposed on appellants. Further, they argue that to accommodate appellants’ demands would require them to violate the First Amendment’s establishment clause. Appellants, on the hand, insist that their opt-out proposal would not impair appellees’ ability to teach reading since appellees would still be permitted to teach reading with the Holt books to the rest of the student body and appellants would still be required to learn the very same reading skills as the other students, albeit with an alternative book. Again, there is a factual dispute which precludes disposition of the issue on summary judgment. A remand is, therefore, necessary for the district court to make factual findings and conclusions of law on this issue as well as to permit reasonable discovery if requested.

In other words, “We’re not deciding this here, but East Tennessee needs to give it another look – for real, this time – and base their decision on all the total facts available.”

Judge Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee would do just that. As instructed, he’d give the fundamentalists a fuller hearing and – hold on to your powdered wigs – decide that maybe they had a point after all. The first time through, he’d found that because the textbook and the school were entirely neutral towards religion in general or specific religions in particular, there was no First Amendment violation. The second time around (fresh from his scolding by the 6th Circuit), Hull found in favor of the parents and even fined the school district to pay for their legal expenses.

Judge Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee would do just that. As instructed, he’d give the fundamentalists a fuller hearing and – hold on to your powdered wigs – decide that maybe they had a point after all. The first time through, he’d found that because the textbook and the school were entirely neutral towards religion in general or specific religions in particular, there was no First Amendment violation. The second time around (fresh from his scolding by the 6th Circuit), Hull found in favor of the parents and even fined the school district to pay for their legal expenses.

Ready for the twist?

The case was again appealed to the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals, this time by the school district. The 6th Circuit overturned the verdict because – wait for it – the textbook and the school were entirely neutral towards religion in general or specific religions in general, so there was no First Amendment Violation.

There’s no record of what Judge Hull might have thrown through the wall or any naughty words he may have uttered upon reading their decision.

Next time we’ll look at the district court’s reasons for changing its mind and the 6th Circuit’s (final) determination of why the parents were going to have to be content with private or home schooling. After that, we’ll return to that salient point I mentioned – the part about what schools are supposed to be doing in the first place, and what happens when the druthers of individuals and the good of society starkly clash.

If you’d like to read my surprisingly well-researched, far less speculative, and 97% politically balanced take on the 45 most important cases in Supreme Court History, go buy my book. In the meantime, you can keep getting the unedited, rambling versions of the process right here for free.

I’ve been researching and drafting what I hope will be the next “Have To” History book. The focus is on the tricky balance between “free exercise” and “establishment” in relation to public education – how to allow students (and to a lesser extent, educators) to express their sincerely held beliefs while still protecting the supposed neutrality of the system towards all things supernatural. It’s fascinating stuff (well, to me, at least), but I confess I’m having trouble with potential titles.

I’ve been researching and drafting what I hope will be the next “Have To” History book. The focus is on the tricky balance between “free exercise” and “establishment” in relation to public education – how to allow students (and to a lesser extent, educators) to express their sincerely held beliefs while still protecting the supposed neutrality of the system towards all things supernatural. It’s fascinating stuff (well, to me, at least), but I confess I’m having trouble with potential titles. Enter Vicki Frost, the mother of several children attending public school in Hawkins County, Tennessee. School had only been a session for a few weeks in the Fall of 1983 when her 6th grade daughter brought home an English textbook containing a story she’d been assigned to read. This story, as it turned out, involved… mental telepathy. Worse, this fictional telepathy was treated by the story as if it were no big deal, despite clearly being un-Biblical.

Enter Vicki Frost, the mother of several children attending public school in Hawkins County, Tennessee. School had only been a session for a few weeks in the Fall of 1983 when her 6th grade daughter brought home an English textbook containing a story she’d been assigned to read. This story, as it turned out, involved… mental telepathy. Worse, this fictional telepathy was treated by the story as if it were no big deal, despite clearly being un-Biblical. District Judge Thomas Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (where the case presumably began) was not initially swayed by the parents’ complaints. He issued a summary judgement dismissing the case – meaning he didn’t find enough substance to their complaint to even hold a full trial. It’s sort of the judicial version of snorting and then asking, “Oh, were you serious?”

District Judge Thomas Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (where the case presumably began) was not initially swayed by the parents’ complaints. He issued a summary judgement dismissing the case – meaning he didn’t find enough substance to their complaint to even hold a full trial. It’s sort of the judicial version of snorting and then asking, “Oh, were you serious?” I’d respectfully suggest, however, that Frost and company made a major strategic error when they included their next example on the “naughty” list. Still quoting Judge Hull:

I’d respectfully suggest, however, that Frost and company made a major strategic error when they included their next example on the “naughty” list. Still quoting Judge Hull: NOTE: I’ve finally completed

NOTE: I’ve finally completed  1. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution contains six specific protections, two of which are related to religion. The “Establishment” Clause says government cannot support one religion over another or promote the idea of religion over non-religion; the “Free Exercise Clause” says government cannot target or hinder a specific religion or religion in general.

1. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution contains six specific protections, two of which are related to religion. The “Establishment” Clause says government cannot support one religion over another or promote the idea of religion over non-religion; the “Free Exercise Clause” says government cannot target or hinder a specific religion or religion in general.  As to the phrase “wall of separation between church and state,” we have Jefferson to either thank (or blame, depending on your point of view). Well, him and the Baptists.

As to the phrase “wall of separation between church and state,” we have Jefferson to either thank (or blame, depending on your point of view). Well, him and the Baptists. Prior to the 14th Amendment, the protections offered by the Bill of Rights applied exclusively to the Federal Government. While most States had similar protections in their own constitutions, these were inconsistent and locally interpreted. The 14th Amendment changed all of that in ways neither immediate nor obvious. Passed in 1868 as part of the ‘Reconstruction Amendments,’ its initial intent was to guarantee full and equal citizenship for Freedmen – newly freed Black Americans.

Prior to the 14th Amendment, the protections offered by the Bill of Rights applied exclusively to the Federal Government. While most States had similar protections in their own constitutions, these were inconsistent and locally interpreted. The 14th Amendment changed all of that in ways neither immediate nor obvious. Passed in 1868 as part of the ‘Reconstruction Amendments,’ its initial intent was to guarantee full and equal citizenship for Freedmen – newly freed Black Americans.