I’m discovering as I continue to draft a follow-up to “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases that it’s more and more difficult to keep things succinct as subject matter nears the 21st century. I’m sharing a few rough drafts along the way partly in hopes a few of you, my Eleven Faithful Followers, might find them interesting, and partly because nothing highlights the problems in a text like posting it live for all the world to see.

Some version of this Talmudic Tale will likely be in the upcoming book. Chances are good, however, that the final results will be considerably more succinct.

Recap of Parts One & Two: Kiryas Joel was (and is) a community of particularly insular Hasidic Jews (the Satmars) in New York. Most of their children attended private religious schools, but they asked the state for assistance providing care and education for their special needs children. Initial efforts to serve these particular children rand into conflict with recent Supreme Court rulings which struck down several public school efforts to serve high needs kids in religious institutions. New York responded by allowing the Satmars to create their own neighborhood and later a publicly funded neighborhood school tailored to their precise boundaries. The Supreme Court struck down this arrangement in a 6 – 3 decision, but even majority justices had differing ideas as to the specifics. The arrangement violated the Establishment Clause. Beyond that…

Justice O’Connor’s Concurrence (and Advice Column)

Justice O’Connor (concurring in part and concurring in the judgment), took the same “you know what you should have done?” approach as she had in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985):

The question at the heart of this case is: what may the government do, consistently with the Establishment Clause, to accommodate people’s religious beliefs? The history of the Satmars in Orange County is especially instructive on this, because they have been involved in at least three accommodation problems, of which this case is only the most recent…

O’Connor walked readers through these accommodations, lamenting the Court’s decisions in Grand Rapids and Aguilar along the way. It wasn’t a purely historical journey; she was leading up to something.

There is nothing improper about a legislative intention to accommodate a religious group, so long as it is implemented through generally applicable legislation. New York may, for instance, allow all villages to operate their own school districts. If it does not want to act so broadly, it may set forth neutral criteria that a village must meet to have a school district of its own; these criteria can then be applied by a state agency, and the decision would then be reviewable by the judiciary.

A district created under a generally applicable scheme would be acceptable even though it coincides with a village which was consciously created by its voters as an enclave for their religious group. I do not think the Court’s opinion holds the contrary.

Want to guess how Kiryas Joel schools operate today? (Come on, take a guess!) It took a few versions before one eeked through federal court approval, but New York eventually figured out how to write a law that only applied to Kiryas Joel without mentioning anything in it that made it clear it could only apply to Kiryas Joel. Thanks, nice judge lady!

I also think there is one other accommodation that would be entirely permissible: the 1984 scheme, which was discontinued because of our decision in Aguilar. The Religion Clauses prohibit the government from favoring religion, but they provide no warrant for discriminating against religion. All handicapped children are entitled by law to government-funded special education…

If the government provides this education on-site at public schools and at nonsectarian private schools, it is only fair that it provide it on-site at sectarian schools as well.

One almost gets the impression Aguilar was ripe for the overturnin’ – say, maybe… three years later?

Finally, O’Connor takes a detour down “Lemon Sucks” Lane:

One aspect of the Court’s opinion in this case is worth noting: Like the opinions in two recent cases, Lee v. Weisman (1992), Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School Dist. (1993), and the case I think is most relevant to this one, Larson v. Valente (1982), the Court’s opinion does not focus on the Establishment Clause test we set forth in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971).

It is always appealing to look for a single test, a Grand Unified Theory that would resolve all the cases that may arise under a particular clause. There is, after all, only one Establishment Clause, one Free Speech Clause, one Fourth Amendment, one Equal Protection Clause…

But the same constitutional principle may operate very differently in different contexts… And setting forth a unitary test for a broad set of cases may sometimes do more harm than good. Any test that must deal with widely disparate situations risks being so vague as to be useless…

It’s nice that O’Connor and Scalia had at least one subject on which they could agree. Speaking of which…

Justice Scalia’s Dissent

Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Clarence Thomas joined Justice Antonin Scalia in his 6000+ word dissent, which led off with a Scalia’s characteristic venom, sarcasm, and intentional point-missing:

The Court today finds that the Powers That Be, up in Albany, have conspired to effect an establishment of the Satmar Hasidim. I do not know who would be more surprised at this discovery: the Founders of our Nation or Grand Rebbe Joel Teitelbaum, founder of the Satmar. The Grand Rebbe would be astounded to learn that, after escaping brutal persecution and coming to America with the modest hope of religious toleration for their ascetic form of Judaism, the Satmar had become so powerful, so closely allied with Mammon, as to have become an “establishment” of the Empire State.

Even Scalia couldn’t have genuinely believed that the First Amendment only kicked in once an institution attained a specific number of members or reached a preset threshold of political power. Playing on the struggles of the Satmar to set up the straw argument that the issue was one of dominance over the rest of New York was disingenuous at best, red-meat ranting better suited to Fox News than the nation’s highest court.

And the Founding Fathers would be astonished to find that the Establishment Clause – which they designed “to insure that no one powerful sect or combination of sects could use political or governmental power to punish dissenters” … has been employed to prohibit characteristically and admirably American accommodation of the religious practices (or more precisely, cultural peculiarities) of a tiny minority sect. I, however, am not surprised. Once this Court has abandoned text and history as guides, nothing prevents it from calling religious toleration the establishment of religion.

Underneath the elitist spittle lies a potentially valid assertion – that the State in this case was simply accommodating a tiny religious group in a practical and neutral way, and that there was no reason to assume the New York Legislature wouldn’t treat others equitably as well. If they proceeded to violate that assumption, the courts would still be there.

Scalia distinguished the political community of Kiryas Joel (which just happened to be full of Satmars) from the religious body of Satmars (who had chosen to live together in Kiryas Joel). A grant of governmental authority to the Satmars would be a potential constitutional violation, but a grant of local governmental authority to a community which just happens to share a religion was not. By the majority’s reasoning, Scalia argued – almost rationally – neither Utah nor New Mexico could have been admitted as States, given their respective monolithic cultures at the time.

Like Abraham challenging God over the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah, Justice Scalia proceeds to asks how many non-Satmars it would have taken for the arrangement to magically become constitutional. Two? Five? A dozen? For a moment, he struck a productive blend of snark and insight – an example of what the rest of his opinion could have accomplished if only he’d resisted the urge to disparage his colleagues personally while mocking their arguments like a middle schooler.

JUSTICE SOUTER’s steamrolling of the difference between civil authority held by a church, and civil authority held by members of a church, is breathtaking. To accept it, one must believe that large portions of the civil authority exercised during most of our history were unconstitutional… The history of the populating of North America is in no small measure the story of groups of people sharing a common religious and cultural heritage striking out to form their own communities. It is preposterous to suggest that the civil institutions of these communities, separate from their churches, were constitutionally suspect…

I have little doubt that JUSTICE SOUTER would laud this humanitarian legislation if all of the distinctiveness of the students of Kiryas Joel were attributable to the fact that their parents were nonreligious commune dwellers, or American Indians, or gypsies. The creation of a special, one-culture school district for the benefit of those children would pose no problem. The neutrality demanded by the Religion Clauses requires the same indulgence towards cultural characteristics that are accompanied by religious belief…

JUSTICE STEVENS’ statement is less a legal analysis than a manifesto of secularism. It surpasses mere rejection of accommodation, and announces a positive hostility to religion – which, unlike all other noncriminal values, the state must not assist parents in transmitting to their offspring.

He’s a bit gentler on Justices Kennedy and O’Connor, each of whom agreed with at least part of his position in their concurrences. Unable to help himself, however, he blows past O’Connor’s criticism of the Lemon Test and focuses instead on the inadequacy of her solution:

Unlike JUSTICE O’CONNOR… I would not replace Lemon with nothing, and let the case law “evolve” … To replace Lemon with nothing is simply to announce that we are now so bold that we no longer feel the need even to pretend that our haphazard course of Establishment Clause decisions is governed by any principle. The foremost principle I would apply is fidelity to the longstanding traditions of our people, which surely provide the diversity of treatment that JUSTICE O’CONNOR seeks, but do not leave us to our own devices.

Lest the reader forget his general disdain for the lesser beings Scalia was daily forced to endure, he concludes with a tidy little summary of the Court’s sins against reason, religion, and America:

The Court’s decision today is astounding. Chapter 748 involves no public aid to private schools, and does not mention religion. In order to invalidate it, the Court casts aside, on the flimsiest of evidence, the strong presumption of validity that attaches to facially neutral laws…

This is unprecedented – except that it continues, and takes to new extremes, a recent tendency in the opinions of this Court to turn the Establishment Clause into a repealer of our Nation’s tradition of religious toleration.

No doubt Scalia is somewhere complaining still, either about the shoddy harp-playing or the lack of air conditioning. Either way, he’s no doubt mocking former colleagues for their roles in the design.

Aftermath

The Supremes would continue to struggle with the line between accommodating religious beliefs and facilitating them beyond constitutional boundaries. Usually, this would involve more familiar scenarios – allowing vouchers to be used at religious schools, arranging for students to lead collective prayer at school events, or including religious symbols in holiday arrangements on public lands.

The Court would also waver on the precise application and usefulness of the Lemon Test. Though criticized by many justices along the way, it continued to prove useful enough to at least work its way into the discussion more often than not.

Kiryas Joel is still going strong, relatively speaking, and recently voted to separate itself even more completely from the Town of Monroe of which it was technically a part. As of 2019, Palm Tree is the first entirely ultra-orthodox town in the U.S.

RELATED POST: Kiryas Joel v. Grumet (1994) – Part One

RELATED POST: Kiryas Joel v. Grumet (1994) – Part Two

RELATED POST: The Jehovah’s Witnesses Flag Cases – Part Two

If you’re interested in far more concise case summaries accompanied by pithy-but-97%-sociopolitically-fair-and-balanced insights, check out

If you’re interested in far more concise case summaries accompanied by pithy-but-97%-sociopolitically-fair-and-balanced insights, check out  In

In  I assume that goes with the gig and that judges don’t take this stuff personally, but I’d have used bad words and probably thrown my gavel through the wall.

I assume that goes with the gig and that judges don’t take this stuff personally, but I’d have used bad words and probably thrown my gavel through the wall. Whoa there, tiger – I thought this was school! No one wants you teaching my kids to think for themselves. That’s why they’ve got me! (OK, that’s not entirely fair. Even the fundamentalists agreed in theory that they wanted their kids to practice critical thinking and such. It’s just that it was supposed to always lead to the same, predetermined outcomes.)

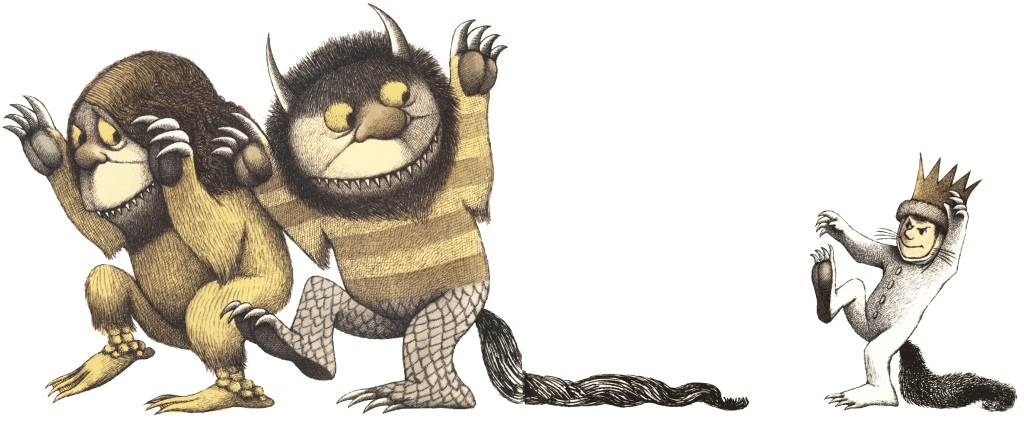

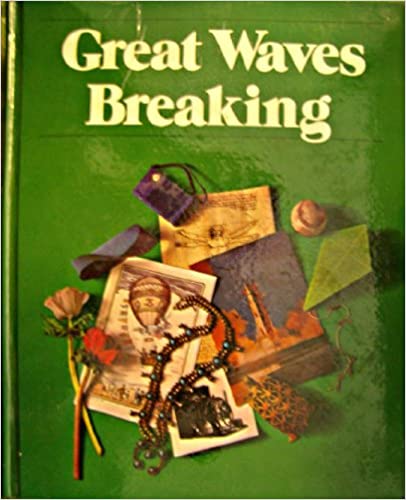

Whoa there, tiger – I thought this was school! No one wants you teaching my kids to think for themselves. That’s why they’ve got me! (OK, that’s not entirely fair. Even the fundamentalists agreed in theory that they wanted their kids to practice critical thinking and such. It’s just that it was supposed to always lead to the same, predetermined outcomes.) 200 hours is equivalent to five weeks of full-time employment doing nothing but finding things wrong with a middle school literature textbook. I actually have a copy of this reader (I tracked it down when I started reading about this case) and I’m not sure there’s 200 hours worth of analysis IN it. The average adult could read it cover to cover in a day, and none of the stories, plays, or poems are particularly complex.

200 hours is equivalent to five weeks of full-time employment doing nothing but finding things wrong with a middle school literature textbook. I actually have a copy of this reader (I tracked it down when I started reading about this case) and I’m not sure there’s 200 hours worth of analysis IN it. The average adult could read it cover to cover in a day, and none of the stories, plays, or poems are particularly complex. In her lengthy testimony Mrs. Frost identified passages from stories and poems used in the Holt series that fell into each category. Illustrative is her first category, futuristic supernaturalism, which she defined as teaching “Man As God.” Passages that she found offensive described Leonardo da Vinci as the human with a creative mind that “came closest to the divine touch.” Similarly, she felt that a passage entitled “Seeing Beneath the Surface” related to an occult theme, by describing the use of imagination as a vehicle for seeing things not discernible through our physical eyes.

In her lengthy testimony Mrs. Frost identified passages from stories and poems used in the Holt series that fell into each category. Illustrative is her first category, futuristic supernaturalism, which she defined as teaching “Man As God.” Passages that she found offensive described Leonardo da Vinci as the human with a creative mind that “came closest to the divine touch.” Similarly, she felt that a passage entitled “Seeing Beneath the Surface” related to an occult theme, by describing the use of imagination as a vehicle for seeing things not discernible through our physical eyes. Here’s where I confess I’m a bit confused. Not at Mrs. Frost – there are always a handful like her out there fighting principalities and powers and spiritual wickedness in children’s poems – but at the other parents and the legal team. There’s a case to be made that the textbook has a New Age-y, “One World” slant to it. But no reasonable adult can think they’re going to convince a federal judge that fostering imagination in children is essentially promoting the occult.

Here’s where I confess I’m a bit confused. Not at Mrs. Frost – there are always a handful like her out there fighting principalities and powers and spiritual wickedness in children’s poems – but at the other parents and the legal team. There’s a case to be made that the textbook has a New Age-y, “One World” slant to it. But no reasonable adult can think they’re going to convince a federal judge that fostering imagination in children is essentially promoting the occult. Or not.

Or not. Have you noticed that while the arguments made other parents or their lawyers are periodically referenced by way of context and summarizing the issues, every explanation as to why there’s no way they’re going to win this case starts with “Vicki First testified that…”?

Have you noticed that while the arguments made other parents or their lawyers are periodically referenced by way of context and summarizing the issues, every explanation as to why there’s no way they’re going to win this case starts with “Vicki First testified that…”? I lied, I will add one more comment. The court moves from why the three cases cited by the parents don’t apply to addressing the more general issue at the heart of this case – the role of public schools in serving society as a whole, not just select parts of it. Pierce Lively was as succinct and stirring as anyone on the highest bench had ever managed:

I lied, I will add one more comment. The court moves from why the three cases cited by the parents don’t apply to addressing the more general issue at the heart of this case – the role of public schools in serving society as a whole, not just select parts of it. Pierce Lively was as succinct and stirring as anyone on the highest bench had ever managed: Print this up and distribute it to every school board, judge, right wing talking head, or believer with a persecution complex. Think of how many problems we could solve if we had general understanding and agreement of this bit alone.

Print this up and distribute it to every school board, judge, right wing talking head, or believer with a persecution complex. Think of how many problems we could solve if we had general understanding and agreement of this bit alone.

While researching what I hope will be an upcoming book about the “wall of separation” as it relates to public education, I came across as case which has fascinated me far out of proportion to its actual importance. Since I try to keep the

While researching what I hope will be an upcoming book about the “wall of separation” as it relates to public education, I came across as case which has fascinated me far out of proportion to its actual importance. Since I try to keep the  Judge Hull opens with a basic summary of the case so far, then adds this intriguing commentary:

Judge Hull opens with a basic summary of the case so far, then adds this intriguing commentary: In 1944, the Supreme Court heard

In 1944, the Supreme Court heard  Second, “COBS”? Their self-selected group name was “COBS”? As in, things we say are up someone’s @$$ when they’re being unreasonably rigid or demanding in their beliefs? It’s not even a great group name spelled out – “Citizens Organized for Better Schools”? Was “Families Asserting Sincere Classroom Involvement Since Textbooks Suck” already taken?

Second, “COBS”? Their self-selected group name was “COBS”? As in, things we say are up someone’s @$$ when they’re being unreasonably rigid or demanding in their beliefs? It’s not even a great group name spelled out – “Citizens Organized for Better Schools”? Was “Families Asserting Sincere Classroom Involvement Since Textbooks Suck” already taken? That’s true inasmuch as judging the belief itself. The government has no business worrying about the validity of specific convictions or doctrines. That doesn’t mean the rest of society has to cooperate with such beliefs, however.

That’s true inasmuch as judging the belief itself. The government has no business worrying about the validity of specific convictions or doctrines. That doesn’t mean the rest of society has to cooperate with such beliefs, however. Most teachers aren’t interested in openly opposing parents or anyone else. We’re just trying to teach a little history or math or whatever. But most of us also won’t go out of our way to add to a kids’ problems if we can avoid it. I realize it drives conservatives crazy to hear this, but at times your suspicions are correct – there are those of us periodically trying to figure out a legal, non-fireable way to do what’s best for your kids. There’s often an unpleasant dissonance, however, between what’s desperately needed by that young person in front of us with no one else to turn to and what’s dictated by cover-your-ass policies. I can shift the conversation back to those multiple choice questions they missed or write them a pass to the school counselor who doesn’t know them from Salvatore Perrone and have a much better chance of keeping my job, but I’ll probably go to Teacher Hell by way of tradeoff.

Most teachers aren’t interested in openly opposing parents or anyone else. We’re just trying to teach a little history or math or whatever. But most of us also won’t go out of our way to add to a kids’ problems if we can avoid it. I realize it drives conservatives crazy to hear this, but at times your suspicions are correct – there are those of us periodically trying to figure out a legal, non-fireable way to do what’s best for your kids. There’s often an unpleasant dissonance, however, between what’s desperately needed by that young person in front of us with no one else to turn to and what’s dictated by cover-your-ass policies. I can shift the conversation back to those multiple choice questions they missed or write them a pass to the school counselor who doesn’t know them from Salvatore Perrone and have a much better chance of keeping my job, but I’ll probably go to Teacher Hell by way of tradeoff. The danger in bending over backwards to accommodate parents or students is that once you’ve established that precedent, there’s no telling what you’ll be expected to do moving forward. Worse, teachers and administrators sound like complete tools whenever they express this up front.

The danger in bending over backwards to accommodate parents or students is that once you’ve established that precedent, there’s no telling what you’ll be expected to do moving forward. Worse, teachers and administrators sound like complete tools whenever they express this up front.