I wrote recently about some of the challenges of being an old white guy from a non-descript middle-class background teaching in a high-poverty, majority-minority school. My goal was to be honest about some of the difficulties without veering into whining or – worse – appearing to criticize my kids. Whatever my struggles, they pale (if you’ll pardon the expression) compared to many of theirs.

I wrote recently about some of the challenges of being an old white guy from a non-descript middle-class background teaching in a high-poverty, majority-minority school. My goal was to be honest about some of the difficulties without veering into whining or – worse – appearing to criticize my kids. Whatever my struggles, they pale (if you’ll pardon the expression) compared to many of theirs.

It’s in that same spirit that I’d like to share some end-of-the-year thoughts for anyone who might find themselves in a similar situation at some point, either as a newbie teacher or as an experienced educator moving into an unfamiliar district. I offer no data, no documentation, and no guarantees – merely hard-won insights based on my subjective experiences.

Still, let’s be honest – I’m much, MUCH wiser than most of those “real” experts, so let’s just assume this list is canon until proven otherwise.

(1) You Don’t Actually “Get It”

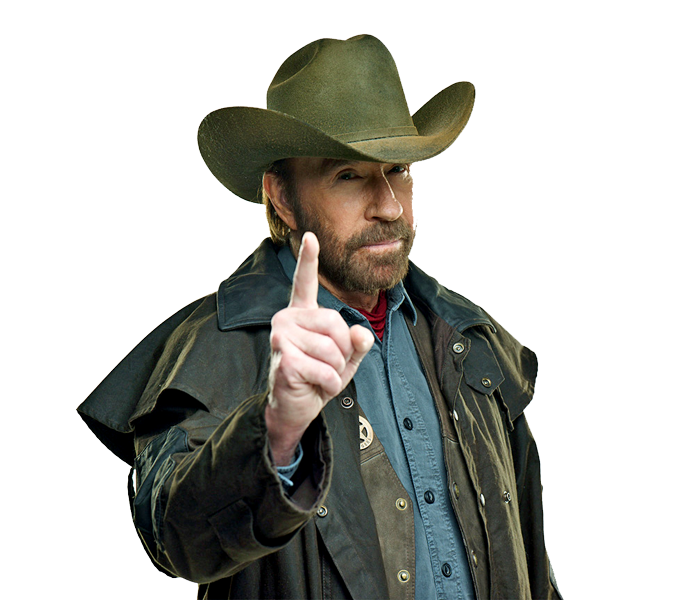

My first year here, a veteran teacher (also white) took me aside and told me to read the books and go to the workshops and do everything I could to understand my kids, but to recognize that we’ll NEVER be as “woke” as they are. “You and I will never quite understand what it’s like to be in their worlds, and if you pretend you do, they’ll see right through you.”

This was (and is) good advice, whatever your demographic details. Do the reading. Pay attention to the conversations. Understand the research. But don’t presume you “get it” unless their world was your world first.

(2) Own Your Biases & Assumptions

Repeat this to yourself out loud at least once each day before you head to work: “I may not think so, but I have biases. I make assumptions and form generalities which are sometimes incorrect. This is a natural, human thing to do and doesn’t make me a bad person – but it can hinder my efforts to be a good teacher unless I’m careful. What should I be questioning about my own thoughts or feelings today?”

Here’s an easy example: many of my students like rap and hip-hop (are those even different things these days?) A significant minority, however, prefer K-Pop, 90’s-era grunge, or some other genre not normally associated with “those kids.” If I simply assume they all like rap and hip-hop, it builds unnecessary barriers from something I’d hoped would build connections. Something with a bit more bite: for years, I’ve called students by their last names – “Mr. ___” or “Miss ___” as a sign of respect and an attempt to elevate expectations. Here, this produces outraged reactions and verbal hostility beyond what I ever could have imagined. This is not hyperbole – it’s a very consistent reaction among 90% of my students when I slip up and forget. Whatever my intentions, it simply doesn’t mean to them what I think it should mean – so I adjust.

It’s actually not that difficult to avoid egregiously offensive stereotyping (assuming you’re not clueless or a complete tool). It’s the little things that catch you off guard and trip you up. Even if you don’t offend or horrify anyone, you’ll feel silly and it won’t do much for that whole “rapport” thing you’re going for.

(3) You Need Thick Skin.

This is true of teaching in general, but (as I wrote about a few weeks ago) broken kids tend to radiate anger and hurt and fear and other emotional concoctions I can’t even properly identify.

It’s fairly rare in my building for a kid to lash out at a teacher directly. I’ll get “attitude” or the occasional snub when attempting to speak to someone (usually from kids I don’t actually have in class, and thus with whom I have little or no relationship). From time to time a student will unexpectedly dig in on something small and escalate the situation past what seems reasonable, but these are separate events to be managed – not an ubiquitous feature of the environment.

In my experience, it’s the sheer volume and intensity of the unspoken emotions which can be crippling. I don’t want to sound overly mystic or touchy-feely, but the real challenge isn’t usually specific kids with specific attitudes, expressions, or behaviors I can identify – it’s the intangible waves of doubt and anger and injustice and posturing and uneasiness.

(4) Be Consistent (Within Reason)

This is a biggie in almost any classroom situation, but I’d argue it’s exponentially more important with kids from broken backgrounds and disenfranchised demographics. If you’re strict about the rules, be the same level of strict every day, with every student, as best you can without obvious harm. If you’re lax about late work, be the same amount lax throughout the year whenever feasible. Perhaps most importantly, leave your personal emotions in the car and be the person they need you to be no matter how you really feel that day.

Teenagers in general have an exaggerated sense of injustice – and my kids take this to whole new levels. They also tend to take things far more personally than other groups. Let a teacher be absent for a few days without providing a good reason (in the eyes of their kids) and even the students who don’t like them begin wrestling with abandonment issues. Speak more harshly than you intend or overlook a question in the middle of a chaotic moment and you might as well have slapped them right in the id.

This doesn’t mean you can’t hold kids accountable or that you should never adjust based on circumstances. Just remain aware of anything which might be perceived as “unfair” and be prepared to justify it to yourself, your kids, and anyone up the chain.

(5) Don’t Expect Consistency In Return.

This, too, can be a “teenager” thing no matter what their demographics. It seems far more volatile with my current kids, however, than with groups I’ve had in the past, not just in terms of attendance, behavior, or academics, but emotionally as well. It’s like they’re controlled by dozens of internal game show wheels constantly being re-spun to see what comes out next.

I have a young lady who rarely (if ever) makes the slightest attempt to participate in anything educational. She’s not always disruptive, but neither will she go through the motions with us just to be cooperative. When I make an effort to speak to her during more relaxed moments (just as I do with most kids from time to time) she’s often resentful, bordering on rude. On the other hand, when I leave her alone for more than a day, she asks me why I’m “ignoring” her and sounds genuinely offended.

Today after school, a young man I don’t remember ever seeing or speaking to saw me in the hall, called my name, then gave me a quick combination fist-bump-bro-hug-finger-snap-something that caught me completely off guard. I think I hid my surprise pretty well, but I still don’t know what I did to earn the exchange.

(6) Be Kind (Not Soft)

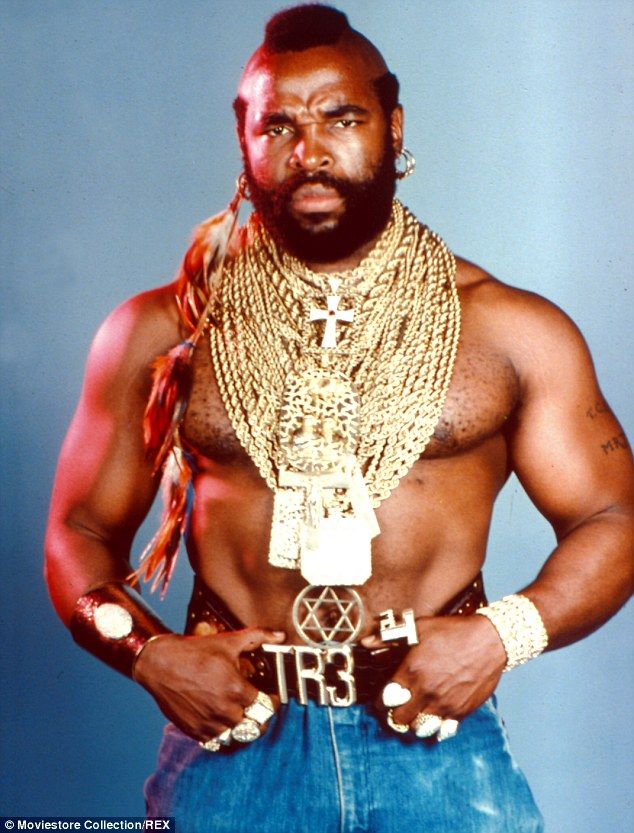

Some groups respond well to sarcasm and abuse as a love language. I was brutal to my suburban freshmen (of all colors), but no matter how cruel I managed to be, they ate it up and decided it made us “tight.” My current kids can be quite ugly with one another without seeming to take it badly, but I know instinctively (and without any doubt) that it would be a terrible idea for me to join the dozens. I can be a good teacher and develop productive relationships with my kids without sharing the dynamics they have with our security team (all of whom are Black) or some of the other staff. It’s not about me proving anything or earning “wokeness” bonus points; it’s about what’s best for the kids in front of me.

I’ve raised my voice to a full class a few times throughout the year when necessary to get their attention, but it’s my conviction that there are few – if any – situations in which an old white man yelling at individual students of color will lead to better outcomes. Maybe it’s the mamby-pamby liberal in me, but I just can’t stomach it. Plus, I’m not sure anger or hostility (no matter how strategic) is particularly effective with any demographics, at least these days. Maybe they never were.

Be firm. Follow through on consequences. Expect the best. But recognize that the sort of posturing or emotional responses which might be excusable (if not ideal) in other circumstances may do irredeemable damage to your relationship with those already marginalized – and possibly to the kids themselves.

(7) Don’t Patronize

Under no circumstances should you try to be cooler or hipper or more “down with the kids” than you truly are. If you actually play that video game, love that album, or eat that food, then bond away when situationally appropriate. But dear god, PLEASE don’t try to use slang you don’t fully understand or emulate speech patterns which are not your own. I’m not suggesting you have to maintain a commitment to the Queen’s English or refuse to learn their language in order to improve communication; I’m merely pointing out what a bad idea it is to be disingenuous – however noble your intentions.

They’ll eventually explain to you anything you’re not understanding about their slang or their approach. Enjoy those moments, but don’t think they free you up to make a fool of yourself.

(8) It’s Not Personal.

As with much on this list, this is a good thing to keep in mind with any students in any situation, but it’s particularly apt with underserved kids. Some days, you’ll feel like you’re making progress and developing some good communication; the next day, they want nothing to do with you or your (seemingly) pointless lessons. If you rely on positive interactions to sustain you, you’ll find yourself deflated by negative feedback or disengaged days. There’s a messy balance between “reading the room” enough to adjust what you’re doing for maximum effectiveness and the need to simply push ahead with what you know to be right even when they’re giving you nothing to draw on.

Keep talking to your peers (the good ones, anyway). It’s OK to vent as long as you soon come back around to the things in your control and your professional and ethical commitments to figuring out what’s best for the young folks in your care – whether they love it or not. Don’t be afraid of asking for help with uncomfortable issues, but neither should you assume that every awkward moment or frustrating interaction is about race, or poverty, or culture, or whatever. Sometimes teaching is just weird and people are just complicated.

Especially teenagers.

RELATED POST: A Leap of Well-Intentioned Delusion

RELATED POST: Of Assumptions and Performative Wokeness

RELATED POST: Why Don’t You Just MAKE Them?

There are so many things about teaching that are difficult to explain to those outside the field. (That may be true of other professions as well, but this is the one I know best.) Even within the world of public education, it’s tricky to balance honesty with optimism, or transparency with teamwork. Too much venting can feed on itself and become entrenched cynicism. An excess of chipper determination, on the other hand, risks building endless castles on the sands of delusion.

There are so many things about teaching that are difficult to explain to those outside the field. (That may be true of other professions as well, but this is the one I know best.) Even within the world of public education, it’s tricky to balance honesty with optimism, or transparency with teamwork. Too much venting can feed on itself and become entrenched cynicism. An excess of chipper determination, on the other hand, risks building endless castles on the sands of delusion.

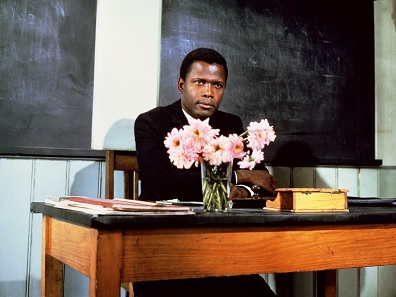

I was 29 years old when I did my student teaching. The first day I was with my new mentor, he asked me at lunch if I’d been paying attention as I sat in his classroom while he talked through whatever that day’s topic happened to be. I said I had. “Great,” he told me. “How ‘bout you take over after lunch?”

I was 29 years old when I did my student teaching. The first day I was with my new mentor, he asked me at lunch if I’d been paying attention as I sat in his classroom while he talked through whatever that day’s topic happened to be. I said I had. “Great,” he told me. “How ‘bout you take over after lunch?” I need to become a hard-ass. Or… hard-er, at least.

I need to become a hard-ass. Or… hard-er, at least.  I have some pretty reasonable policies regarding late work – if I followed them. They’re not particularly draconian. Anything skill-based can be attempted multiple times, and in some circumstances students can “earn” retakes of quizzes or whatever. There are enough grades throughout the year that a rough week or two isn’t enough to do lasting harm. Even poor test-takers should be fine if they take care of everything else.

I have some pretty reasonable policies regarding late work – if I followed them. They’re not particularly draconian. Anything skill-based can be attempted multiple times, and in some circumstances students can “earn” retakes of quizzes or whatever. There are enough grades throughout the year that a rough week or two isn’t enough to do lasting harm. Even poor test-takers should be fine if they take care of everything else.  Students are going to mess up. They’re going to get behind – which, in a history class, changes everything. If there’s going to be collaboration, or meaningful discussions, or if we’re going to go truly wild with some tasty primary sources or thesis-writing, there has to be SOME expectation that everyone is on the same proverbial (or literal) page, content-wise. Otherwise, they might as well all stay home and take the class online, dispelling the illusion that we’re a “class” and not just a bunch of people sharing classroom space here and there.

Students are going to mess up. They’re going to get behind – which, in a history class, changes everything. If there’s going to be collaboration, or meaningful discussions, or if we’re going to go truly wild with some tasty primary sources or thesis-writing, there has to be SOME expectation that everyone is on the same proverbial (or literal) page, content-wise. Otherwise, they might as well all stay home and take the class online, dispelling the illusion that we’re a “class” and not just a bunch of people sharing classroom space here and there.  There’s a good argument to be made for building personal responsibility and school skills and life skills as well via the relatively benign experience of actual deadlines and cutoffs; I haven’t even really wrestled with that aspect yet. Kannimayketup Swamp has pretty much dominated my concerns – probably because of all the damned irony involved.

There’s a good argument to be made for building personal responsibility and school skills and life skills as well via the relatively benign experience of actual deadlines and cutoffs; I haven’t even really wrestled with that aspect yet. Kannimayketup Swamp has pretty much dominated my concerns – probably because of all the damned irony involved.

My school is on trimesters, so coming back wasn’t a new start so much as picking up where we left off. Still, having two weeks to regroup and get a jump on some of the planning for this month was, well… it may have saved my life. At least emotionally.

My school is on trimesters, so coming back wasn’t a new start so much as picking up where we left off. Still, having two weeks to regroup and get a jump on some of the planning for this month was, well… it may have saved my life. At least emotionally.