It’s so tempting sometimes to actually teach my kids some history. But I can’t.

Well, I CAN – it’s just I know I shouldn’t. Not very often. Teaching them stuff is, um… bad.

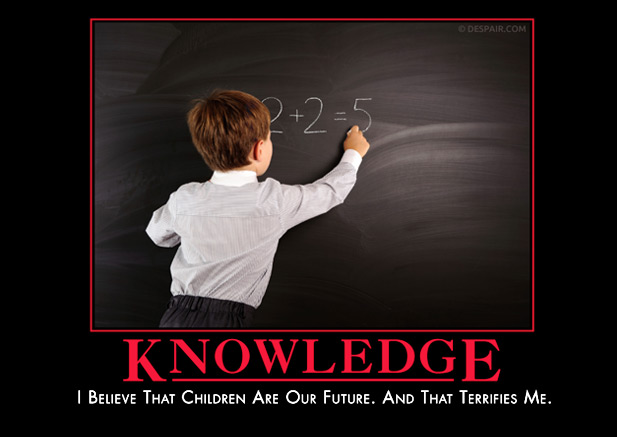

Direct instruction has been weighed and found wanting, as the amount of information available is simply too vast and the needs of the next generation too unpredictable to settle on this or that bucket of knowledge as canon. We are called, it seems, to teach them to think! To question! To boldly go where no student has gone before!

If you read the various criticisms of lectures and other teacher-driven, direct-instruction-ish stuff, you’d think the underlying problem is that such things are ineffective. That’s not true.

I give pretty sweet lectures, packed with content and connection and interaction with students – all sorts of edu-goodness. When former students come back to visit, or email me years later, they may thank me for pushing coherent thesis sentences – but they remember with enthusiasm the stuff from the lectures. They tell me how it was the first time they’d liked history, or understood government, or whatever, and tell me stories of how something learned therein came in handy in subsequent academia.

The problem isn’t that my activities or direct instruction aren’t effective; the problem is that they leave me doing so much of the work. As a department and a district, we’ve prioritized teaching kids to think, and to learn, and to function. We’re trying to make our students into students.

We’re trying to teach them to ask various types of questions effectively, to dig into documents or statistics or pictures and ponder what those sources do or don’t communicate, and how they do or don’t communicate it. We want them to read and write coherently, and above all else – and this is the killer – we’re trying to teach them not to be helpless little nurslings in the face of every idea, task, or challenge.

That part feels damn near impossible most days. If ignorance is a mighty river, we’re that ichthus fish swimming against the tide – losing out to the gar of apathy and the tuna of better-things-to-do.

Seriously, we should make shirts.

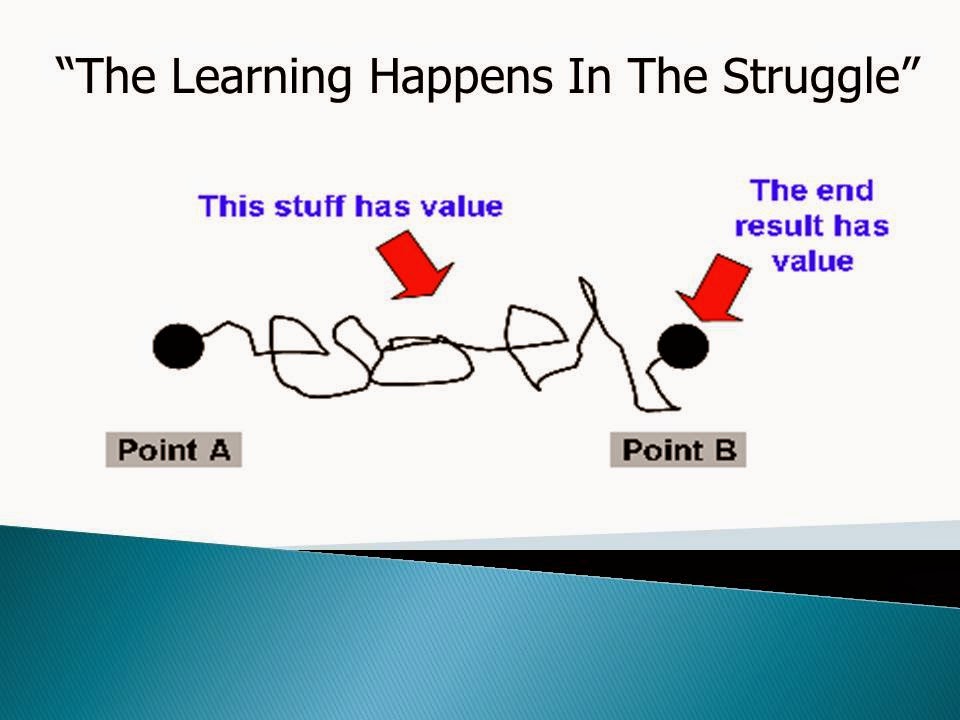

This is where the idealists jump in to argue that we can do both – we can teach content THROUGH the skills! Whoever’s doing the struggling is doing the learning! Let’s celebrate this breakthrough!

The learning DOES happen in the struggle – this is dogma to me. I would argue, however, that we must inculcate and consciously teach the struggle. Our darlings do not, by and large, come with a built in appreciation of struggle – at least in application to education. Some struggle enough getting through the rest of their worlds and have little energy left for academic wrestling matches. Others push themselves quite impressively through their own little zone of proximal development while playing music or sports or video games, but lack enthusiasm for transferring the principle to unpacking the Federalist #10.

It’s that teaching of the struggle that’s killing me.

It’s not an intelligence problem, or an attitude problem. It’s not even the challenge of the content.

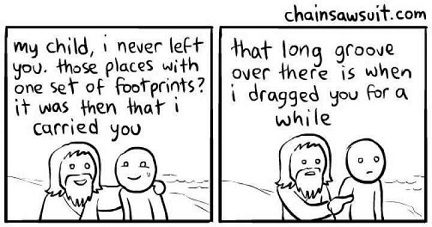

It’s the mindset of helplessness and a sort of dazed, bewildered hurt they experience at the least of my expectations. That’s what I can’t seem to overcome. I don’t know how to fix it. I must fix it, of course – we’re no longer allowed to let kids fail in any way, shape or form – we must save them repeatedly or they’ll never learn to be independent, self-directed learners.

Forget analyzing the Federalist Papers, I can’t get them to reference my class webpage for help or assignments they’ve missed, let alone videos I’ve posted for them to watch. And getting them to check their own grades online rather than expect I spend half of every class period EVERY DAY explaining what they haven’t turned in (“but I wasn’t here that day”) – you’d think I’d handed them a scalpel and suggested they do their own colon splicing.

It’s not that they don’t know how the internet works – Google is their info-god. It simply never occurred to them that not EVERYTHING associated with school would be photocopied and hand-delivered to their backpack as many times as they can lose it. The drive – the initiative – the risk-taking craziness required to click on a few things or look on more than one page or ask questions of the people around them – it’s simply beyond many of them.

We’ve taught them to be completely helpless. We’ve trained them not to move until we tell them exactly what to do, and how, and then do it for them. The learning does indeed happen in the struggle, but how do they learn to struggle without, well… struggling?

We’ve taught them to be completely helpless. We’ve trained them not to move until we tell them exactly what to do, and how, and then do it for them. The learning does indeed happen in the struggle, but how do they learn to struggle without, well… struggling?

I don’t say this to curse them or bust out the standard “kids these days” routine. It’s a new generation and we’re going to have to figure out some new ways to reach them. That’s fine – that’s why I make the big bucks. I’m SO up for the challenge.

Most days.

But it makes me tired. The number of ways students go out of their way to make their own learning untenable is fascinating. The internal mechanisms protecting them from forward momentum are legion. The currently trending vision of an edu-spirational Arcadia where students are natural learners if only the damn teachers would get out of the way is ridiculous. Come watch 200 kids in the commons a half-hour before school starts staring bored into space rather than risk reading or finishing their math and tell me how self-actuated they are.

I love them, you understand – but I drag them into the light kicking and screaming, if at all. Meanwhile, I hear repeatedly that I should be letting them do more of the dragging.

I’m not supposed to spoon-feed them, but they won’t chew – and they’re starving, informationally-speaking.

I’m not giving up on them, but more and more I’m wondering if the skills and mindset I’m failing to instill are worth the trade-off of basic knowledge and cultural literacy I could lead them through instead. AND the results are clearly measurable – we like that, right?

I feel myself giving in… letting go of the idealistic ‘oughta work’ and looking longingly towards the ‘would actually result in learning.’ I feel myself slipping off-program, avoiding my admins, and lying to my PLC about what I’m really doing in class that day.

I feel myself giving in… letting go of the idealistic ‘oughta work’ and looking longingly towards the ‘would actually result in learning.’ I feel myself slipping off-program, avoiding my admins, and lying to my PLC about what I’m really doing in class that day.

I want to just teach them stuff about history and government and things that actually matter to them in the real world right now. I want to see that look where they ‘get it’ and remember it and love me for it. I don’t care if they become self-directed learners THIS year. I don’t care if they don’t master document analysis or political cartoons or thesis sentences anymore.

I’m tired. Maybe I’ll just teach a little… just this week… I won’t get hooked. I can quit any time I want – I swear. Just say the word and I’ll… I’ll flip my lesson and establish mastery-based standards achieved through collaboration, I promise! But just give me a little… one PowerPoint over the Progressives… one crazy story about Andrew Jackson and I’ll stop.

I promise.

Related Post: Hole in the Wall Education

Related Post: A School of Reindeer

There’s a kerfuffle going on in Texas (again) and Colorado (huh?) regarding the level of flag-waving patriotism in history textbooks and curriculums, including APUSH. The short version is this:

There’s a kerfuffle going on in Texas (again) and Colorado (huh?) regarding the level of flag-waving patriotism in history textbooks and curriculums, including APUSH. The short version is this: The Modern Liberal Academics are upset that these flag-waving right-wing extremists want to whitewash American history to feed their predetermined paradigm of American Exceptionalism. There’s something Orwellian (or at least Valdimir Putinian) about euphemizing (or simply ignoring) travesties like slavery, genocide, and Woodrow Wilson. The Academics would like more emphasis on effective questioning and understanding multiple points of view. American schools should be shaping good world citizens ready to confront things of which we cannot yet conceive, not drones painted red, white, and blue.

The Modern Liberal Academics are upset that these flag-waving right-wing extremists want to whitewash American history to feed their predetermined paradigm of American Exceptionalism. There’s something Orwellian (or at least Valdimir Putinian) about euphemizing (or simply ignoring) travesties like slavery, genocide, and Woodrow Wilson. The Academics would like more emphasis on effective questioning and understanding multiple points of view. American schools should be shaping good world citizens ready to confront things of which we cannot yet conceive, not drones painted red, white, and blue. This is about choosing

This is about choosing  I liked Aquaman.

I liked Aquaman. Why can we not allow Thomas Jefferson the same intellectual and moral complexity we accept in Mystique? Why accommodate a Batman who does dark twisted things so soccer moms feel safe but insist on ‘hero’ or ‘villain’ labels for Andrew Jackson or Malcolm X? Can we not accept that real people – who lived monumental lives and did big stuff – might be at least as unpredictable as Magneto or Malcolm Reynolds?

Why can we not allow Thomas Jefferson the same intellectual and moral complexity we accept in Mystique? Why accommodate a Batman who does dark twisted things so soccer moms feel safe but insist on ‘hero’ or ‘villain’ labels for Andrew Jackson or Malcolm X? Can we not accept that real people – who lived monumental lives and did big stuff – might be at least as unpredictable as Magneto or Malcolm Reynolds? In the same way that the people around you are so much more meaningful, useful, interesting, when they allow you to see something beyond the façade… in the same way heroes are far more heroic when you know what a mess they are, but they keep trying to do the right thing anyway… our history, our icons, our story resonates far more – not less – when we do our best to lay it all out there as whatever it is.

In the same way that the people around you are so much more meaningful, useful, interesting, when they allow you to see something beyond the façade… in the same way heroes are far more heroic when you know what a mess they are, but they keep trying to do the right thing anyway… our history, our icons, our story resonates far more – not less – when we do our best to lay it all out there as whatever it is. There is a good case to be made that part of our job as educators is to prepare students for the ‘real world’ – whatever that is. We could thus argue that deadlines and responsibility are valid goals of public education. In the ‘real world’, you’re expected to do stuff when it needs to get done. Rolling in at 3 p.m. with “hey, here are those burgers you asked for during the lunch rush” isn’t going to cut it, nor will you get paid half if you simply don’t make them at all.

There is a good case to be made that part of our job as educators is to prepare students for the ‘real world’ – whatever that is. We could thus argue that deadlines and responsibility are valid goals of public education. In the ‘real world’, you’re expected to do stuff when it needs to get done. Rolling in at 3 p.m. with “hey, here are those burgers you asked for during the lunch rush” isn’t going to cut it, nor will you get paid half if you simply don’t make them at all. And no matter how modern or flipped or inquiry-based I may try to be, there are still things that require grading. I hate grading, but there’s a limit to how much I can job out to students and still be able to sleep at night. There are things they can learn from peer evaluation, but half-a-class spent announcing that #1 is A, #2 is C, etc., is an embarrassing waste of limited time. Besides, most of what I’m grading isn’t multiple choice.

And no matter how modern or flipped or inquiry-based I may try to be, there are still things that require grading. I hate grading, but there’s a limit to how much I can job out to students and still be able to sleep at night. There are things they can learn from peer evaluation, but half-a-class spent announcing that #1 is A, #2 is C, etc., is an embarrassing waste of limited time. Besides, most of what I’m grading isn’t multiple choice. Yeah, yeah – poor overworked teacher. But this isn’t about me missing my tee time after school. What it means instead is that when I am working, at my desk or at home, I’m spending far more time and energy trying to figure out why little Johnny has handed in a page of Level Questions over some – well, over SOMETHING, I’m not sure WHAT – and whether or not they correspond to anything he’s missing in the gradebook – than I’m spending coming up with better ways to teach Johnny’s 150 peers the next unit. Flexible deadlines and nurturing late work policies mean I spend more time grading than preparing, or teaching, or collaborating, or whatever.

Yeah, yeah – poor overworked teacher. But this isn’t about me missing my tee time after school. What it means instead is that when I am working, at my desk or at home, I’m spending far more time and energy trying to figure out why little Johnny has handed in a page of Level Questions over some – well, over SOMETHING, I’m not sure WHAT – and whether or not they correspond to anything he’s missing in the gradebook – than I’m spending coming up with better ways to teach Johnny’s 150 peers the next unit. Flexible deadlines and nurturing late work policies mean I spend more time grading than preparing, or teaching, or collaborating, or whatever. How many angry lil’ Republicans are created this way – barely into high school and already learning that the harder they work, the more they are expected to drag along those who can’t or won’t, often at the expense of their own progress? At least under the old framework the best and brightest were merely ignored and marginalized under the assumption they’d still pass state tests and stay out of discipline trouble – under this new approach we can actively punish them for being responsible!

How many angry lil’ Republicans are created this way – barely into high school and already learning that the harder they work, the more they are expected to drag along those who can’t or won’t, often at the expense of their own progress? At least under the old framework the best and brightest were merely ignored and marginalized under the assumption they’d still pass state tests and stay out of discipline trouble – under this new approach we can actively punish them for being responsible! My daughter wanted a new backpack last year about this time, and after several unfulfilling stops, we ended up at Target. The selection was a bit slim, but she found something that seemed like a good combination of practical and not-entirely-embarrassing, and we took it to the nearest register.

My daughter wanted a new backpack last year about this time, and after several unfulfilling stops, we ended up at Target. The selection was a bit slim, but she found something that seemed like a good combination of practical and not-entirely-embarrassing, and we took it to the nearest register.

I remember losing my composure and at some point nearly yelling that “THE COMPUTERS. ARE. NOT. IN. CHARGE!!!” before blacking out. Whatever happened seems to have worked – a few days later, my phone showed up.

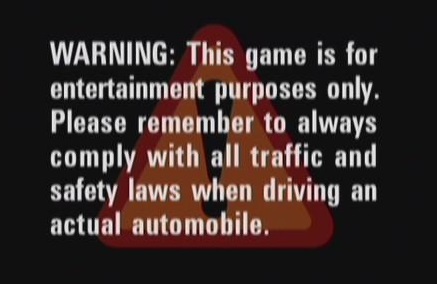

I remember losing my composure and at some point nearly yelling that “THE COMPUTERS. ARE. NOT. IN. CHARGE!!!” before blacking out. Whatever happened seems to have worked – a few days later, my phone showed up. There’s a legal division somewhere covering someone’s corporate behind by advising me not to throw a rhino at a helicopter. We need a rule for that? Is there a label on the rhino?

There’s a legal division somewhere covering someone’s corporate behind by advising me not to throw a rhino at a helicopter. We need a rule for that? Is there a label on the rhino? We don’t judge teachers or their students on what they do well, but on what items they miss. Inspire your kids all you like, but if you don’t happen to be demonstrating requirements 4a, 4b, 7, and 11 and have your learning objectives on the board when your administrator drops in for five minutes, you suck. Write with passion, but if the MLA heading is on the top left instead of the top right, I can’t and won’t read it. It’s all about the policies.

We don’t judge teachers or their students on what they do well, but on what items they miss. Inspire your kids all you like, but if you don’t happen to be demonstrating requirements 4a, 4b, 7, and 11 and have your learning objectives on the board when your administrator drops in for five minutes, you suck. Write with passion, but if the MLA heading is on the top left instead of the top right, I can’t and won’t read it. It’s all about the policies. It’s not working, by the way – somehow no matter what we do, there’s always that bottom 5%.

It’s not working, by the way – somehow no matter what we do, there’s always that bottom 5%. I’m a bad person.

I’m a bad person. Don’t get me wrong – it’s just peachy keen swell that throwing a few computers in the middle of an impoverished village and making sure no teachers interfere practically guarantees a bunch of eight-year olds will master calculus, cure cancer, and reverse climate change. Here’s to the success of every one of those dusty darlings and even newer, bigger opportunities for them to challenge themselves AND the dominant paradigm. Seriously.

Don’t get me wrong – it’s just peachy keen swell that throwing a few computers in the middle of an impoverished village and making sure no teachers interfere practically guarantees a bunch of eight-year olds will master calculus, cure cancer, and reverse climate change. Here’s to the success of every one of those dusty darlings and even newer, bigger opportunities for them to challenge themselves AND the dominant paradigm. Seriously. Maybe it would be better to do the entire building… eleven hundred freshmen set free to learn with a bank of Dells and no silly adults with their stifling expectations. Imagine the money saved on staff – and computers never take personal days or violate professional dress code!

Maybe it would be better to do the entire building… eleven hundred freshmen set free to learn with a bank of Dells and no silly adults with their stifling expectations. Imagine the money saved on staff – and computers never take personal days or violate professional dress code! I’m not unsympathetic. I get what these writers and speakers are going for. Most are trying to make the very valid point that when we try to cram kids’ heads full of 87-pages of curriculum standards compiled by committees and approved by states to be tested by bubbles, we are unlikely to either fill their buckets OR light their fires.

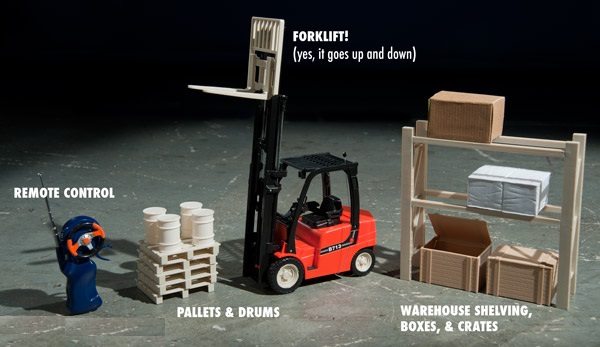

I’m not unsympathetic. I get what these writers and speakers are going for. Most are trying to make the very valid point that when we try to cram kids’ heads full of 87-pages of curriculum standards compiled by committees and approved by states to be tested by bubbles, we are unlikely to either fill their buckets OR light their fires. It’s not. Remember that Oregon Trail game we were all so excited about a few decades ago? That’s still about as cutting edge as educational games have managed, and that’s not even what most virtual learning is attempting.

It’s not. Remember that Oregon Trail game we were all so excited about a few decades ago? That’s still about as cutting edge as educational games have managed, and that’s not even what most virtual learning is attempting. There are glaring problems with this system, some within the school’s control and many more without. The biggest problem with the current model is also the most substantial barrier to all this self-directed learning we keep hearing will save us all – state legislatures dictate most of what’s supposed to be “important” and decide how these things will be assessed.

There are glaring problems with this system, some within the school’s control and many more without. The biggest problem with the current model is also the most substantial barrier to all this self-directed learning we keep hearing will save us all – state legislatures dictate most of what’s supposed to be “important” and decide how these things will be assessed.