In the Election of 1860, despite almost unanimous opposition from southern states, Abraham Lincoln was elected. Between the announcement of his victory (it took a little longer to tally everything back then) and his inauguration in early March, seven southern states announced they were leaving the Union.

From Georgia’s declaration of secession:

The people of Georgia having dissolved their political connection with the Government of the United States of America, present to their confederates and the world the causes which have led to the separation. For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery. They have endeavored to weaken our security, to disturb our domestic peace and tranquility, and persistently refused to comply with their express constitutional obligations to us in reference to that property…

A brief history of the rise, progress, and policy of anti-slavery and the political organization into whose hands the administration of the Federal Government has been committed will fully justify the pronounced verdict of the people of Georgia. The party of Lincoln, called the Republican party, under its present name and organization, is of recent origin. It is admitted to be an anti-slavery party… anti-slavery is its mission and its purpose…

From Mississippi’s:

In the momentous step which our State has taken of dissolving its connection with the government of which we so long formed a part, it is but just that we should declare the prominent reasons which have induced our course.

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.

They all pretty much go like this. The format consciously echoes the Declaration of Independence – the basic proclamation followed by a list of complaints explaining their decision to bail.

Based on these documents, produced by the Southern states for the explicit purpose of proclaiming to the world the causes of their secession, the main issues seemed to be (1) slavery, (2) slavery, and – in some cases – (3) slavery.

Based on these documents, produced by the Southern states for the explicit purpose of proclaiming to the world the causes of their secession, the main issues seemed to be (1) slavery, (2) slavery, and – in some cases – (3) slavery.

South Carolina took the lead as they always did when racial equity needed to be crushed:

But an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the Institution of slavery has led to a disregard of their obligations… {The northern} States… have enacted laws which either nullify the Acts of Congress, or render useless any attempt to execute them… Thus the constitutional compact has been deliberately broken…

Those {non-slaveholding} States have assumed the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions*; and have denied the rights of property** established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of Slavery***; they have permitted the open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace****… They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.

*i.e. ‘slavery’

**i.e. ‘slaves’

***i.e. ‘Slavery’ – oh wait, it says it that time, doesn’t it? My bad.

****i.e., abolitionists

South Carolina was upset that the North allowed so much discussion of things which threatened their way of life and went against their beliefs. They listed as one of their central reasons for trying to break the country their collective outrage that other states weren’t doing enough to stifle debate.

Their little white feelings were hurt and their dominant role in the world inconvenienced. Poor things.

Seriously, it goes on for several pages like that.

Was Lincoln’s election really such a threat to their way of life? Maybe. Not according to Lincoln, it wasn’t, but the new Republican Party openly advocated for restrictions on slavery – particularly in terms of limiting its expansion. Perhaps that was a debate worth having, in the context of the times.

Was Lincoln’s election really such a threat to their way of life? Maybe. Not according to Lincoln, it wasn’t, but the new Republican Party openly advocated for restrictions on slavery – particularly in terms of limiting its expansion. Perhaps that was a debate worth having, in the context of the times.

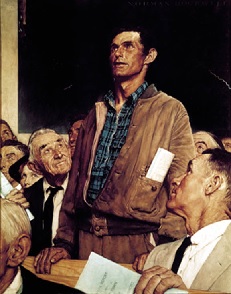

But the time for debate and compromise, it seems, was over. The writing was on the wall, and the South feared that reason and decency would no longer produce the outcome they wished. So, they circumvented both and tried to change the rules. They chose theatrics over the much more difficult path of introspection.

…those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.

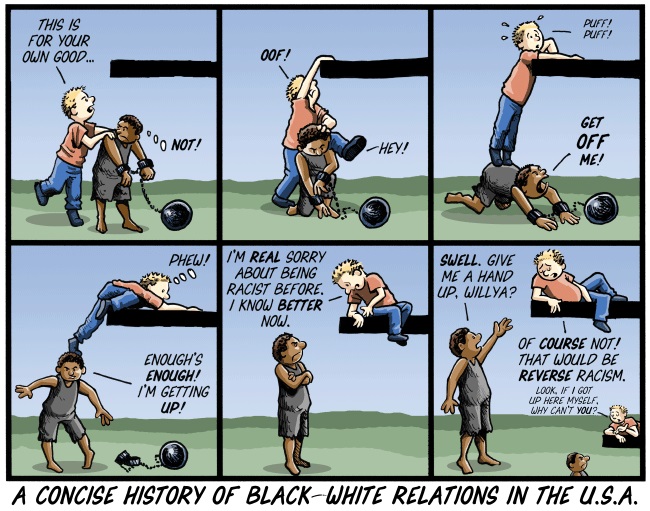

Slavery was not simply about physical bondage, as central as that was. It required a type of brainwashing and systemic manipulation so that the slave remained perpetually hopeless, and largely helpless. They were kept ignorant of all but the most basic skills or concepts. Slave-owners – the same ones who would soon rebel based on their right not to be bossed around – were forbidden by law from teaching their slaves to read, allowing them to learn to swim, or otherwise expanding their horizons beyond what was absolutely necessary.

The shocking thing about slave revolts isn’t that they happened – it’s that there were so few of them. Most resistance was covert, cultural – playing dumb, breaking things, maintaining an identity bewildering to white slave-owners.

The Underground Railroad was pretty amazing, but the total numbers carried to freedom were miniscule compared to the size of the institution. And yet…

…incited by emissaries, books and pictures…

Do you feel the past reaching out to you through that line? I got goosie-bumps.

“We don’t like the thinking prompted by your teachers, your books, your visuals. We don’t appreciate you complicating their world or ours by introducing problematic ideas. Ignorance is bliss, buddy – our version of reality is good enough, despite its apparent inability to withstand the slightest scrutiny.”

“We don’t like the thinking prompted by your teachers, your books, your visuals. We don’t appreciate you complicating their world or ours by introducing problematic ideas. Ignorance is bliss, buddy – our version of reality is good enough, despite its apparent inability to withstand the slightest scrutiny.”

See? I coulda been a Southerner.

The problem with education is that it gets people thinking. The problem with thinking is that they don’t always think what we want them to. And, in the South’s defense, sometimes a little knowledge IS a dangerous thing – we’ll look at that in Part Two.

The South understood the dangers of expanded thinking. As lovers of tradition – and of being in charge – they had little taste for new or threatening ideas. They codified narrow-mindedness as a virtue and framed the ignorance of those in bondage as a mercy.

Turns out the human race is pretty good at legal, intellectual, and moral contortions when it’s time to rationalize something we really really want to be true.

After the War – which they lost – the South continued to fight against dangerous levels of education for others. They also began denying their own explicitly stated causes for trying to leave in the first place. When you feel strongly enough that your cause is just, reality is just one more adversity to nobly overcome for the greater good.

That’s Part Three.

My goal throughout is to avoid directly referencing Representative Dan Fisher and his ilk – not even once – no matter how analogous the issues involved.

Oops!

OK – just once, then.

RELATED POST: A Little Knowledge, Part Two – Forever Unfit

RELATED POST: A Little Knowledge, Part Three – Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire

It’s dangerous to project backwards regarding motivations and intentions, but it seems that even when public education was barely a thing, they realized it would soon become essential if their sons were to flourish in the next generation. I don’t know if they were worried about ‘personal fulfillment’ stuff as well, but I’m an idealist, so… let’s assume maybe they did.

It’s dangerous to project backwards regarding motivations and intentions, but it seems that even when public education was barely a thing, they realized it would soon become essential if their sons were to flourish in the next generation. I don’t know if they were worried about ‘personal fulfillment’ stuff as well, but I’m an idealist, so… let’s assume maybe they did.

Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops… Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them…

Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops… Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them… This is not my anti-capitalism rant. I’ll leave that to Tom Joad and his spirit moving among the hungry children and such. I’m more or less a Libertarian, but the Libertarian Ideal in MY interpretation requires a capable citizenry with actual options and real opportunity. It’s fine to support free will and full consequences for our actions, but to believe this and sleep at night we need something akin to a ‘equitable starting position’ or the proverbial ‘level playing field’.

This is not my anti-capitalism rant. I’ll leave that to Tom Joad and his spirit moving among the hungry children and such. I’m more or less a Libertarian, but the Libertarian Ideal in MY interpretation requires a capable citizenry with actual options and real opportunity. It’s fine to support free will and full consequences for our actions, but to believe this and sleep at night we need something akin to a ‘equitable starting position’ or the proverbial ‘level playing field’.  Ma was right – no one knew what it was gonna be like. Rose was pregnant, so that’s literary, and Connie – ironically – wasn’t far off track in terms of how the future was going to work for those able to claim it. As in, NOT the Joads.

Ma was right – no one knew what it was gonna be like. Rose was pregnant, so that’s literary, and Connie – ironically – wasn’t far off track in terms of how the future was going to work for those able to claim it. As in, NOT the Joads.

I

I  The Senate was intended to be the more austere, deliberative body – holding longer terms and intended as a balance on the more reactionary House of Representatives, elected every two years and thus presumably more responsive to the whims of the people. Jefferson’s parenthetical commentary is a nod to the superior role and trustworthy wisdom of the crude mess-secretors from a few sentences before.

The Senate was intended to be the more austere, deliberative body – holding longer terms and intended as a balance on the more reactionary House of Representatives, elected every two years and thus presumably more responsive to the whims of the people. Jefferson’s parenthetical commentary is a nod to the superior role and trustworthy wisdom of the crude mess-secretors from a few sentences before.

These few instances were reversed to smooth the transition into Reconstruction and maintain the almost cultish commitment Americans had to property rights – and, apparently, irony. The freedmen received nothing.

These few instances were reversed to smooth the transition into Reconstruction and maintain the almost cultish commitment Americans had to property rights – and, apparently, irony. The freedmen received nothing. You all remember Hayes, right? A President for whom it was worth giving up the closest we’d ever come to realizing our founding ideals?

You all remember Hayes, right? A President for whom it was worth giving up the closest we’d ever come to realizing our founding ideals? That’s the suffrage part. If Jefferson was correct about the spiritual and moral benefits of ‘laboring in the earth’, working the land of another may or may not have been worth partial divine credit. In terms of ‘vested interest’ in our national success, whatever support black Americans lent to their country came without terrestrial reciprocation.

That’s the suffrage part. If Jefferson was correct about the spiritual and moral benefits of ‘laboring in the earth’, working the land of another may or may not have been worth partial divine credit. In terms of ‘vested interest’ in our national success, whatever support black Americans lent to their country came without terrestrial reciprocation.

When my kids were little, we used to go to Bishop’s Cafeteria to eat with my dad. He was old, and old people like cafeterias – so we went.

When my kids were little, we used to go to Bishop’s Cafeteria to eat with my dad. He was old, and old people like cafeterias – so we went.

“DAD!”

“DAD!”  I’m overgeneralizing, of course – there were hundreds of tribes and cultures and such – but by and large, they weren’t doing proper America things with the lands they claimed as theirs. And, as with the Jello, subjected to repeated wiggling but remaining unconsumed, our frontiersmen forebears weren’t impressed by the arguments of those claiming that land ownership requires neither cultivation nor mall-building.

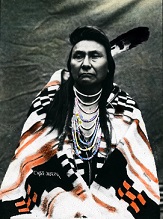

I’m overgeneralizing, of course – there were hundreds of tribes and cultures and such – but by and large, they weren’t doing proper America things with the lands they claimed as theirs. And, as with the Jello, subjected to repeated wiggling but remaining unconsumed, our frontiersmen forebears weren’t impressed by the arguments of those claiming that land ownership requires neither cultivation nor mall-building.

Conflict with Mexico was not much different. Their culture was nothing like most Amerindian peoples, but neither did we particularly fathom or appreciate their social structure, economic mores, or anything else – nor they ours. Perhaps outright disdain for one another played a larger role than with the Natives, and certainly by that point the sheer momentum of Westward Expansion eclipsed whatever underlying values or beliefs had fueled it a generation prior, but whatever the immediate motivations, the same sense of unquestioned rightness oozed from the words and letters of those pinche gabachos

Conflict with Mexico was not much different. Their culture was nothing like most Amerindian peoples, but neither did we particularly fathom or appreciate their social structure, economic mores, or anything else – nor they ours. Perhaps outright disdain for one another played a larger role than with the Natives, and certainly by that point the sheer momentum of Westward Expansion eclipsed whatever underlying values or beliefs had fueled it a generation prior, but whatever the immediate motivations, the same sense of unquestioned rightness oozed from the words and letters of those pinche gabachos  They were assigned a value system and lifestyle they didn’t want, with the full weight of state and federal governments forcing compliance. They were assigned the worst land on which to practice this new system, and given inadequate tools and other supplies. The stakes were incredibly high – at best, they were expected to emulate those with the right equipment, in which case they could perhaps almost survive as second-class citizens. More likely, they would fail, starve, or simply give up – this not being a game they’d wished to play anyway.

They were assigned a value system and lifestyle they didn’t want, with the full weight of state and federal governments forcing compliance. They were assigned the worst land on which to practice this new system, and given inadequate tools and other supplies. The stakes were incredibly high – at best, they were expected to emulate those with the right equipment, in which case they could perhaps almost survive as second-class citizens. More likely, they would fail, starve, or simply give up – this not being a game they’d wished to play anyway.

“Those who labor in the earth…” I suppose he could have just said “farmers,” but this paints a more vivid picture to set up where he’s going. It’s not about a role in the economy or the food chain – it’s about the agency of individuals, applied not merely to ground or soil but to the “earth”. It’s a wide-angle lens on an idealized way of life – Jefferson’s strength.

“Those who labor in the earth…” I suppose he could have just said “farmers,” but this paints a more vivid picture to set up where he’s going. It’s not about a role in the economy or the food chain – it’s about the agency of individuals, applied not merely to ground or soil but to the “earth”. It’s a wide-angle lens on an idealized way of life – Jefferson’s strength. Farmers worked 365 days a year. Soil still needing tilling on your birthday, cows needed milked on Christmas, and no matter how sick you might be, those crops weren’t going to reap themselves. It was labor-intensive and the hours were long, and yet after doing all you could do, all day every day – you waited.

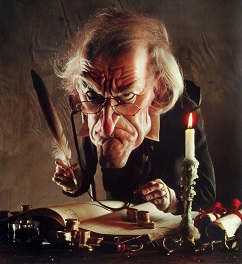

Farmers worked 365 days a year. Soil still needing tilling on your birthday, cows needed milked on Christmas, and no matter how sick you might be, those crops weren’t going to reap themselves. It was labor-intensive and the hours were long, and yet after doing all you could do, all day every day – you waited. Jefferson had a distrust of bankers, stock markets, or anything financial industry-ish – so much so that he took great personal pride in never having the foggiest idea how to make his estate solvent (he died in substantial debt). Farmers raised essentials. They produced raw materials which could be woven into clothing, smoked for pleasure, eaten to survive. “Real wealth.”

Jefferson had a distrust of bankers, stock markets, or anything financial industry-ish – so much so that he took great personal pride in never having the foggiest idea how to make his estate solvent (he died in substantial debt). Farmers raised essentials. They produced raw materials which could be woven into clothing, smoked for pleasure, eaten to survive. “Real wealth.” Land ownership promotes solidity, character, ethereal virtues reflected in wise words and actions – valuable in and of themselves, sure, but especially necessary in a nation relying on the people themselves to provide beneficial leadership – directly or through their choices regarding representation.

Land ownership promotes solidity, character, ethereal virtues reflected in wise words and actions – valuable in and of themselves, sure, but especially necessary in a nation relying on the people themselves to provide beneficial leadership – directly or through their choices regarding representation. That he so easily adjusts his faith to accommodate current events I leave to you to interpret as you see fit.

That he so easily adjusts his faith to accommodate current events I leave to you to interpret as you see fit.