There are times I just get GIDDY over a good document. (Yes, my life is that lame.) Imagine my euphoria, then, when I came across this enticing missive from Helen Churchill Condee published in Harper’s Weekly, February 23, 1901…

Not all of us are successful in life; possibly this is because we have not had a fair chance. The government of these United States, while it is looked upon as a cold, unapproachable body, like a corporation, once conceived the beneficent plan of giving a chance for success to any of its sons who chose to take it.

What a rich framing of the initial land runs in Oklahoma – “a beneficent plan of giving a chance for success to any of its sons who chose to take it.”

I could spend a week on that sentence. Beneficent? Really? I thought the Boomers and others raised such a fuss the powers-that-be finally caved.

Look at the nuance in ‘chance’ for success (kinda like the right to ‘pursue’ happiness) for any ‘sons’ (it was still a man’s world, in law and on paper at least) who ‘chose to take it’. The American Dream may have evolved since the days of Horatio Alger (think Little Orphan Annie as a dude, or Oliver Twist without the British accent), but the ‘live right, dare big, work hard’ ethic of such tales still drove expansion and those willing to migrate into opportunity.

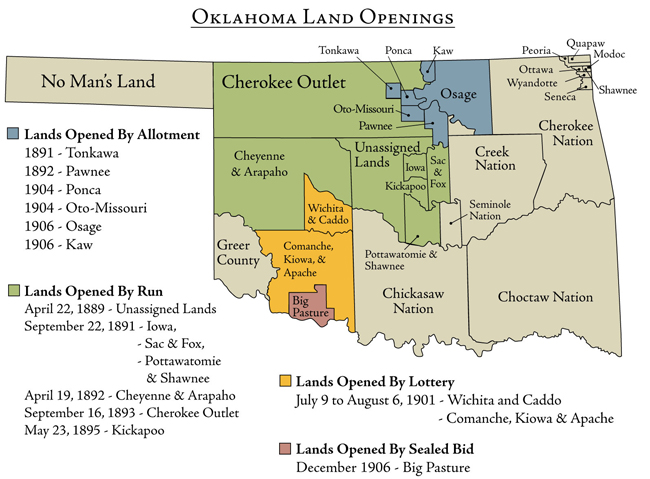

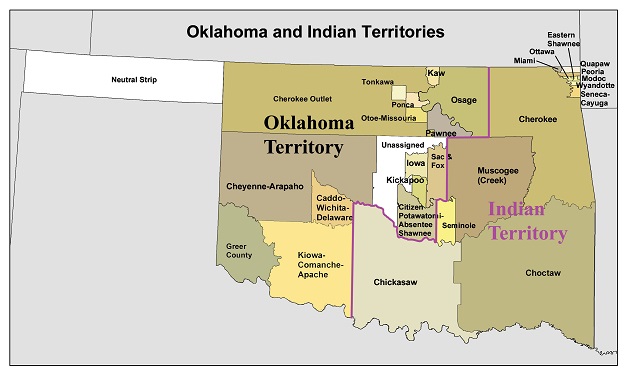

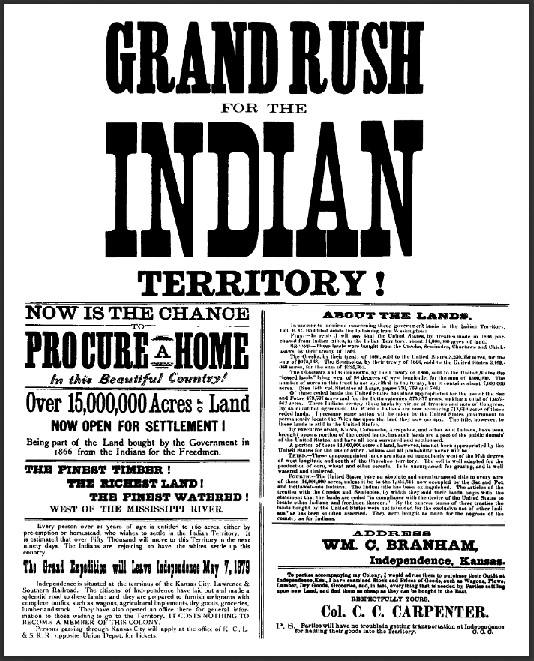

In pursuance of this plan a tract of land containing about three million acres was thrown open in the middle of the Indian Territory, and every one was at liberty to take possession of one hundred and sixty acres without price. This was the beginning of Oklahoma, a Territory with a romantic and marvelous history of prosperity crowded into the short time of eleven years…

This is the chance Uncle Sam is to give his unsuccessful sons and certain of his daughters.

When was the last time you thought of Oklahoma as a land ‘with a romantic and marvelous history of prosperity’? And this was almost a decade before the oil boom! But Condee was right – our little state-to-be had become the last great hope for white homesteading anywhere on the continent.

Which, you know, was exciting for white homesteaders, at least…

The new tract is the reservation of the Kiowa and Comanche Indians, with the possibility of the inclusion of the Wichita lands. It is not easy to decide on the justice of the question so far as the original owner, the Indian, is concerned.

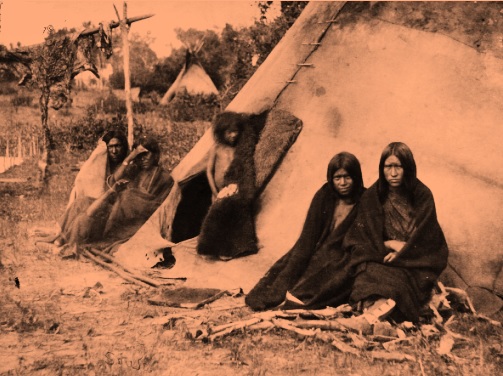

Those who live far from him look with disapproval on the gradual crowding into smaller and yet smaller space, of the taking away of his hunting-grounds and giving him the beef issue, of beggaring him by way of forcing civilization, of breaking even the treaties sworn to hold “as long as grass grows and water runs.”

It’s easy to forget in retrospect that many of the same complexities we recognize in history were being wrestled with as current events. Condee pairs land allotment – the most recent process by which Amerindians had been stripped of their land – with the food allotments arranged by the same treaties. Which was more destructive, she seems to suggest – taking away the source of their own culture and self-provision, or maneuvering them into reliance on the outstretched whims of federal government?

As to ‘beggaring him by way of forcing civilization’ – I… I’m simply too aquiver to even analyze that one effectively.

The U.S. picked a largely unjust war with Mexico, to be sure, but at least at some point war was declared, whatever the pretext. The vast majority of Amerindians were ethnically cleansed through handshakes and smiles and warmest assurances. The 19th century saw the U.S. perfect the art of stabbing you in the back for your own good, then resenting the few shoddy bandages it felt compelled to throw your way.

Or am I reading too much into seven words?

Those who live near the reservations see the Indian through different eyes. They regard him as a lazy, opulent child of fortune, possessing fertile lands, which lie fallow, himself rich through the simplicity of his needs and his share of the interest on the $43,000,000 which the government holds invested for his tribes.

There’s a whole separate post to be written about paper wealth and Amerindians. Most of the wilder tales involve oil money, but the dynamic here is similar – ‘lazy’ and ‘opulent’ sets a nice tension, and surely Condee recognized the cruel irony inherent in ‘child of fortune’.

The idea of untapped resources – especially LAND – was anathema to the white way of thinking. For the last generation of homesteaders all too aware their opportunities were quickly vanishing, it only fueled their resentment to see it ‘going to waste’.

And how much do you love Condee’s subtle rhetoric – ‘rich through the simplicity of his needs’ flowing almost as an afterthought into ‘and the interest on the $$$…’?

It angers a man who tills every acre of his quarter-section with unfailing industry to place his family above want to see his Indian neighbor, with boundless lands, cultivating but a tiny patch of corn, yet living in a cabin, keeping cattle, and driving off contentedly to receive from the government agent the issue of groceries and beef which the white man can only get in return for hard-earned dollars.

Condee would have made a great historian. (She actually did just about everything BUT that – she’s a story in and of herself.) Kudos to the white lady from the North who’s so able to put the reader into such a variety of other mindsets while maintaining her own narrative voice to hold it together.

Without the perspective lent by distance, the envious fail to see that the Indian’s rations are only a crumb of the just return he should be entitled to for evacuating all the continent except a few little reservations; and the white man covets. He does it so ingeniously, too, that its results work like logical morality, and crimes are committed under the excuse of civilizing the Indian.

‘Its results work like logical morality’ – Oh. My. God. Can you excuse me? I need a moment alone.

How easily we vainly assumed that kind of insight can only come in retrospect, with the benefit of distance and the perspective it allows. But at least one pithy babe was unraveling the human condition contemporaneously.

The lands about to be opened are some that have long been coveted by the white men. Greed of land grows on those who hold it.

But perhaps more on those who don’t.

I can’t help myself. We’ll have to continue this one – and talk a little more about Helen Churchill Condee. I’m still giddy – aren’t you?

RELATED POST: A Chance In Oklahoma, Part II

RELATED POSTS: 40 Credits & A Mule, Parts I – VII

RELATED POSTS: Boomers & Sooners, Parts I – V

Ernie Pyle (1900-1945) was a journalist specializing in bringing the normal to intimate life through the written word.

Ernie Pyle (1900-1945) was a journalist specializing in bringing the normal to intimate life through the written word.  The Library of Congress has a fairly impressive newspaper search availabe at

The Library of Congress has a fairly impressive newspaper search availabe at

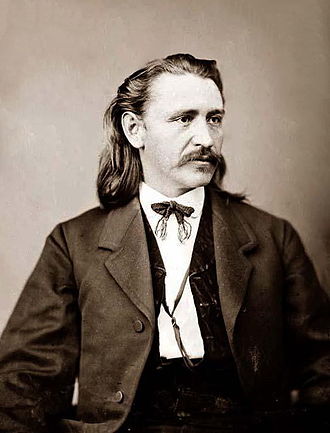

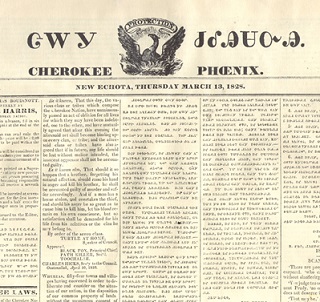

Elias C. Boudinot was the son of Elias “I Don’t Have A Middle Name” Boudinot, who’d helped to establish and edit the first Amerindian newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. Remember Sequoyah and his syllabary? Boudinot was the guy who turned it into movable type so it could be printed easily.

Elias C. Boudinot was the son of Elias “I Don’t Have A Middle Name” Boudinot, who’d helped to establish and edit the first Amerindian newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. Remember Sequoyah and his syllabary? Boudinot was the guy who turned it into movable type so it could be printed easily. The rest of the younger Boudinot’s upbringing took place in Connecticut with his mother’s family – a well-off people of some status who supported Christian missionaries among the Cherokee. These weren’t the yelling and shaking godly fists types of missionaries, or the Spanish Priests variety who thought enslavement was good for the sinful savage. These were the kind of missionaries who tried to make themselves legitimately useful among those to whom they were missioning, but who also hoped to eventually change a few key traditions and values – like, say… killing those who sign away tribal lands.

The rest of the younger Boudinot’s upbringing took place in Connecticut with his mother’s family – a well-off people of some status who supported Christian missionaries among the Cherokee. These weren’t the yelling and shaking godly fists types of missionaries, or the Spanish Priests variety who thought enslavement was good for the sinful savage. These were the kind of missionaries who tried to make themselves legitimately useful among those to whom they were missioning, but who also hoped to eventually change a few key traditions and values – like, say… killing those who sign away tribal lands. Elias C. Boudinot became in many ways the worst version of his father’s progressive vision – a political figure who worked in both Indian Territory (I.T.) and Washington, D.C., often more in support of railroads and national expansion than anything traditionally Cherokee. The excerpts below are from a letter he wrote which created quite a stir after its publication in 1879.

Elias C. Boudinot became in many ways the worst version of his father’s progressive vision – a political figure who worked in both Indian Territory (I.T.) and Washington, D.C., often more in support of railroads and national expansion than anything traditionally Cherokee. The excerpts below are from a letter he wrote which created quite a stir after its publication in 1879. The Reconstruction Treaties made with the various ‘Civilized Tribes’ after the Civil War include ‘freedmen’ explicitly and persistently. This choice of words was presumably intended to reinforce the postbellum reality that former slaves of the various tribes were now free, and under these treaties were to receive full rights and privileges of tribal citizenship. In this case, this meant access to land under the same terms as any other member of their respective tribes.

The Reconstruction Treaties made with the various ‘Civilized Tribes’ after the Civil War include ‘freedmen’ explicitly and persistently. This choice of words was presumably intended to reinforce the postbellum reality that former slaves of the various tribes were now free, and under these treaties were to receive full rights and privileges of tribal citizenship. In this case, this meant access to land under the same terms as any other member of their respective tribes.  While the Massacre at Wounded Knee (which effectively ended Amerindian resistance on the Great Plains) was a decade away, Boudinot was correct that the vast majority of those who were to be ‘relocated’ had already been moved. This ‘extra land’ in Indian Territory was unlikely to be assigned anytime soon.

While the Massacre at Wounded Knee (which effectively ended Amerindian resistance on the Great Plains) was a decade away, Boudinot was correct that the vast majority of those who were to be ‘relocated’ had already been moved. This ‘extra land’ in Indian Territory was unlikely to be assigned anytime soon. Enter Charles C. Carpenter, a former Civil War… er, ‘participant’ in various capacities, both official and not. Apparently a fan of the recently deceased George Armstrong Custer, Carpenter sported long golden curls and buckskins. A commanding officer wrote of him that “he adds great shrewdness to the reckless courage which he undoubtedly possesses.”

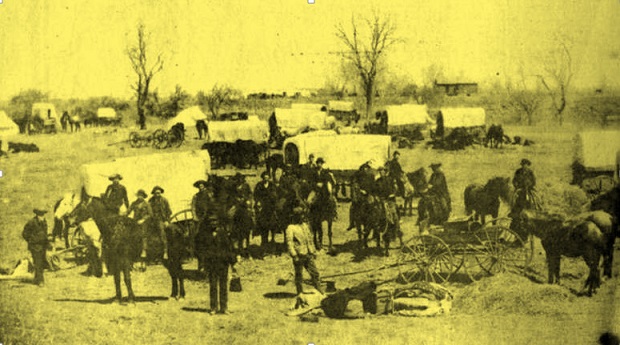

Enter Charles C. Carpenter, a former Civil War… er, ‘participant’ in various capacities, both official and not. Apparently a fan of the recently deceased George Armstrong Custer, Carpenter sported long golden curls and buckskins. A commanding officer wrote of him that “he adds great shrewdness to the reckless courage which he undoubtedly possesses.” He was persuasive enough, though, to organize at least one big ‘boomer’ push into Indian Territory, where the limits of the government’s determination would be tested by a few brave souls willing to rough it and even risk trouble with the law to grab their little piece of the American Dream. Or at least, that was how they framed themselves.

He was persuasive enough, though, to organize at least one big ‘boomer’ push into Indian Territory, where the limits of the government’s determination would be tested by a few brave souls willing to rough it and even risk trouble with the law to grab their little piece of the American Dream. Or at least, that was how they framed themselves.

Liberty is a tricky concept. On the surface it seems so simple – you are either free, or you are not. You have options and opportunity, or you do not.

Liberty is a tricky concept. On the surface it seems so simple – you are either free, or you are not. You have options and opportunity, or you do not. Only they can’t. Most can’t afford to live the way they wish to live or go all the places they wish to go. They may have to work just to eat. Social mores change around them as well, and while they may still technically behave any way they wish, they’ll begin to lose friends and employment, and their romantic options will be… unpromising. If they’re not particularly attractive or bright, the possibilities are even more limited. In a few years’ time, they’re back in mom and dad’s garage apartment, tolerating dinner conversation and being called ‘Brandon’ instead of ‘Sharktooth’ so they can eat something that doesn’t come in a box with a toy.

Only they can’t. Most can’t afford to live the way they wish to live or go all the places they wish to go. They may have to work just to eat. Social mores change around them as well, and while they may still technically behave any way they wish, they’ll begin to lose friends and employment, and their romantic options will be… unpromising. If they’re not particularly attractive or bright, the possibilities are even more limited. In a few years’ time, they’re back in mom and dad’s garage apartment, tolerating dinner conversation and being called ‘Brandon’ instead of ‘Sharktooth’ so they can eat something that doesn’t come in a box with a toy. The Wizard of Oz is full of examples. Dorothy and her cohorts encounter all sorts of opposition attempting to limit their ‘negative liberty.’ Angry trees, flying monkeys, and that green chick who sang ‘Defying Gravity’ all try to restrict or destroy them. When the primary source of this opposition – the Wicked Witch of the West – was removed, their negative liberty went way, way up!

The Wizard of Oz is full of examples. Dorothy and her cohorts encounter all sorts of opposition attempting to limit their ‘negative liberty.’ Angry trees, flying monkeys, and that green chick who sang ‘Defying Gravity’ all try to restrict or destroy them. When the primary source of this opposition – the Wicked Witch of the West – was removed, their negative liberty went way, way up! Freedman after the Civil War were suddenly given ‘negative liberty’. They could go wherever they wished, and do whatever they wanted. Most, though, ended up doing pretty much what they’d been doing before – working the soil for food and shelter. They lacked ‘positive liberty’. Why the fuss over

Freedman after the Civil War were suddenly given ‘negative liberty’. They could go wherever they wished, and do whatever they wanted. Most, though, ended up doing pretty much what they’d been doing before – working the soil for food and shelter. They lacked ‘positive liberty’. Why the fuss over  Sometimes the answer is that they don’t actually have the negative liberty we assume. A central theme of the #BlackLivesMatter movement is that police departments across the country forcibly prevent them from pursuing happiness, and sometimes take their lives as well. The Joads discovered serpents in the Promised Land of California – armed authorities limiting their movements, their speech, and their lifespans. Those are limits on ‘negative liberty’. Those are chains.

Sometimes the answer is that they don’t actually have the negative liberty we assume. A central theme of the #BlackLivesMatter movement is that police departments across the country forcibly prevent them from pursuing happiness, and sometimes take their lives as well. The Joads discovered serpents in the Promised Land of California – armed authorities limiting their movements, their speech, and their lifespans. Those are limits on ‘negative liberty’. Those are chains.