There are certainly plenty of wonderful individual people of faith around, including many Christians.

There are certainly plenty of wonderful individual people of faith around, including many Christians.

I feel obligated to open with this acknowledgement (disclaimer?) because my next several posts are going to focus on clashes between religious folks and public education which have been in the news recently, and it seems like every time you come across a story about someone asserting their Christian beliefs via legislation or the courts, they’re doing it for one of three reasons: (1) they want more government money for something without having to follow the same rules as everyone else, (2) they want the government to like their religion best and tell everyone about it more often because that’s “freedom of religion,” or (3) they want to be horrible to some group of people everyone else is supposed to be kind to.

All in all, it doesn’t paint a very flattering picture of the group as a whole. Then again, we’ve seen their voting habits, so…

Texas Demands Empty Proclamations of Faith Without Substance

The Texas State Legislature has passed a bill requiring that any public schools which just happen to end up with one or more “In God We Trust” signs in their possession post them as prominently as possible. (As of this writing, it’s waiting on the Governor’s signature.) Presumably, they’re hoping this will pass constitutional muster thanks to a combination of factors:

- The signage will be donated, not paid for by state tax dollars.

- “In God We Trust” is our national motto – a statement of patriotism (supposedly), not religion.

- The Supreme Court has previously ruled that some religious statements are so drained of meaning as to no longer trigger “wall of separation” issues.

The “national motto” thing is a remnant of our 1950s terror of all things Communist. If spiritual purity and a commitment to capitalism weren’t synonyms before World War II, they certainly became so by the time of color television. The Commies were “godless,” so one way the U.S. could stand tall was to insert things like “under God” into the Pledge of Allegiance and make “In God We Trust” our official national motto. (For those of you unfamiliar with the teachings of Jesus, he was very big on public rituals and governmental gestures of support.)

This conflation of all things red, white, and blue with orthodox Christianity has only intensified since. In the hearts and minds of the controlling (and voting) majority of American faithful, you can’t love Jesus and favor gun control legislation. You can’t take communion and oppose tax breaks for the uber-wealthy. And it’s easier for an elephant to go through restorative justice training than for a Black man to have equal rights in the eyes of the law because look they must have been asking for it or they wouldn’t have the mark of Cain to begin with. It’s hardly a coincidence that the same Texas legislature pushing the “In God We Trust” signage passed a law requiring sports teams to play the National Anthem before every game.

From FoxNews.com:

Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick was a staunch advocate for the bill, dubbed the “Star Spangled Banner Protection Act.” The measure was first introduced in February after the Dallas Mavericks briefly stopped playing the national anthem before their home games.

“Texans are tired of sports teams that pander, insulting our national anthem and the men and women who died fighting for our flag,” Patrick said in a statement in April. “The passage of SB 4 will ensure Texans can count on hearing the Star Spangled Banner at major sports events throughout the state that are played in venues that taxpayers support. We must always remember that America is the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

Notice the title – the “Star Spangled Banner Protection Act.” Because patriotism, like faith, apparently can’t survive without government propping it up by force. Note also the claim that American soldiers fight and die “for our flag.” Not our values, not our Constitution, and certainly not our people – for the cloth and the symbols and the rituals.

Notice the title – the “Star Spangled Banner Protection Act.” Because patriotism, like faith, apparently can’t survive without government propping it up by force. Note also the claim that American soldiers fight and die “for our flag.” Not our values, not our Constitution, and certainly not our people – for the cloth and the symbols and the rituals.

I won’t even try to make sense of mandating adherence to a ritual in order to remind us we’re the land of the free. Modern GOP “reality” gives me a headache. Instead, back to those godless public schools…

“Ceremonial Deism”

In 2004, the Supreme Court heard a case involving the “under God” bit added to the Pledge in the 1950s. A non-custodial parent objected to his daughter being exposed to this daily chant of devotion in her local public school. The Court avoided deciding the case on its merits, finding instead that the plaintiff lacked standing to sue (the girl’s mother, who legally had custody, had no objections to the Pledge).

Several concurring opinions, however, indicated that had they addressed the issue itself, the Pledge would have been fine. The best-known was this bit from Justice Sandra Day O’Connor:

Given the values that the Establishment Clause was meant to serve… I believe that government can… acknowledge or refer to the divine without offending the Constitution. This category of “ceremonial deism” most clearly encompasses such things as the national motto (“In God We Trust”), religious references in traditional patriotic songs such as The Star-Spangled Banner, and the words with which the Marshal of this Court opens each of its sessions (“God save the United States and this honorable Court”). These references are not minor trespasses upon the Establishment Clause to which I turn a blind eye. Instead, their history, character, and context prevent them from being constitutional violations at all.

In other words, “under God” was no more spiritual than saying “bless you” when someone sneezed or “OMG!” when you see a cool TikTok video. It was purely ceremonial, stripped of substance by repetition and years of historical impotence.

That’s what Texas is going for with their motto requirement – something barely constitutional because it lacks the slightest spiritual or religious meaning in the eyes of the courts or, presumably, the citizenry at large. Otherwise, it would be blatantly unconstitutional.

A Moment Of Pray—Er… Silence

The same basic approach was taken by numerous states when passing “moment of silence” legislation. These laws require school announcements each day to include 3-4 seconds of silence (some statutes specify a full minute) during which students can “reflect, meditate, or pray” or some variation thereof. These laws pass constitutional muster because they’re so pointless. Sure, kids can pray – but they don’t have to. Of course, they can also pray silently before the moment of silence, or after it. Kids have never ever EVER in the history of the United States been prohibited from praying silently during the school day, or from praying collectively and out loud on school grounds as long as it’s not in the middle of class. Never.

The same basic approach was taken by numerous states when passing “moment of silence” legislation. These laws require school announcements each day to include 3-4 seconds of silence (some statutes specify a full minute) during which students can “reflect, meditate, or pray” or some variation thereof. These laws pass constitutional muster because they’re so pointless. Sure, kids can pray – but they don’t have to. Of course, they can also pray silently before the moment of silence, or after it. Kids have never ever EVER in the history of the United States been prohibited from praying silently during the school day, or from praying collectively and out loud on school grounds as long as it’s not in the middle of class. Never.

Legislators tried the same disingenuous strategy with the Ten Commandments as well, but the “HOW IS THAT RELIGIOUS?!?” argument somehow didn’t stick with that one. Opening with “Thou shalt have no other gods before me” kinda gave it away.

So if these moments and postings and such are neutered, meaningless symbols, why do some legislators fight so hard to make them happen?

Conservatives have somehow persuaded a majority of religious voters that these little token victories – the ones that slide past First Amendment concerns specifically because they lack substance – are somehow pushing Jesus back into public schools or securing God’s blessings on America. Mumbling “under God” or posting “In God We Trust” operates as a sort of code phrase, opening a spiritual portal for the Lord Almighty to swoop back in and take His rightful place in the big leather chair in the principal’s office. Statues become woodland creatures again, teenagers stop being interested in sex or any music recorded after 1957, and Common Core was never even invented, let alone mandated by many of these exact same legislators.

(OK, that last one wouldn’t be so bad.)

Let There Be (Gas)Light

In other words, the only reason to pass these laws is because those supporting them believe they ARE statements of faith. They DO matter in distinguishing America’s official religion (which they’re willing to pretend isn’t official in order to secure it as such) from all of those other belief systems (which have no place in public schools because of the First Amendment).

In other words, the only reason to pass these laws is because those supporting them believe they ARE statements of faith. They DO matter in distinguishing America’s official religion (which they’re willing to pretend isn’t official in order to secure it as such) from all of those other belief systems (which have no place in public schools because of the First Amendment).

Religious legislators have learned to go through the motions of manufacturing pseudo-secular reasons for these theological breaches. They assert that a “moment of silence” rewrites the chemistry of the teenage brain each morning or that the Ten Commandments are purely historical context for the U.S. Constitution (despite the two having not so much as a single line in common). The trick is to do this while still celebrating the banishment of the White Witch from Narnia with their constituents, who believe their nation is so great and their God so powerful that neither can survive without such gestures.

Legislators aren’t the only ones perfectly aware of the power of these little religious “victories.” They’re a reminder to anyone outside the cell group that they don’t belong. You atheists, Buddhists, Hindus, or Muslims, along with you LGBTQ+ teens and anyone else who isn’t showing proper deference to state-mandated religious and patriotic rituals – you can stay for now, but you are outsiders. You. Don’t. Count. And honestly, you’re ruining everything for the good people – the ones who believe and do the right things, in unison, whenever we’re told.

If you think I’m overstating it, go visit another country for a few years where the dominant culture is different than yours and send your kids to school there. Or just ask one of those gay or atheist types you don’t let your kids hang out with. Maybe they’ll try to explain it.

The Governor has about ten days from the time a bill is presented to either sign or veto it in Texas. You’ll know if it becomes law because you’ll hear a cock crow three times.

I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating.

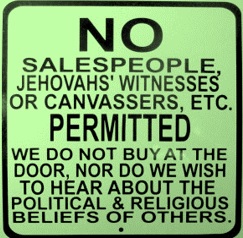

I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous.

After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous. Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different.

Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different. West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school.

West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school. In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days:

In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days: The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved:

The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved: Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well.

Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well. The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s.

The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s. Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…”

Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…” I recently finished

I recently finished  In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective.

In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective. We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court.

We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court.