Level One, Level Two, and Level Three Questions

It is sometimes helpful to talk about ‘Levels’ of Questions. This concept is not new, and different workshops or different subject areas define the levels a little differently. That doesn’t matter – what matters is clarifying them in a way you can live with in order to give your students a tool for asking better and more diverse questions. These aren’t things I’d quiz my kids on per se – at least not in the sense of having them put stuff in categories and count them right or wrong. They’re tools, not scientific classifications.

Level 1 Questions

Deal with factual information you can find printed in the story / document / whatever. They usually have ONE correct answer. In other words, Level One Questions Are Answered With Facts.

Level 1 Questions often…

- clarify vocabulary or basic facts

- check for Understanding

- ask for more information

It is often difficult to ask or answer Level 2 Questions without plenty of Level 1 information!

Examples: Who led Confederate forces at the Battle of Gettysburg? When did Abraham Lincoln die? How many people died of disease or other non-combat causes during the Civil War? Where is Antietam?

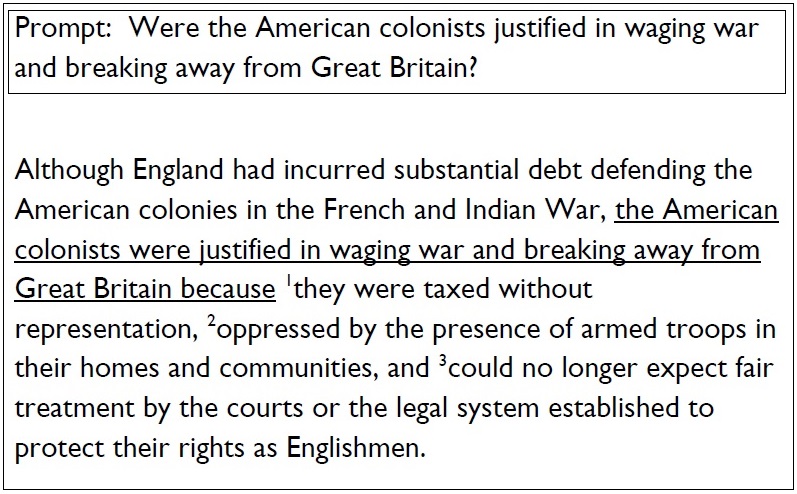

Level 2 Questions

Deal with factual information but can have more than one defensible answer. Although there can be more than one ‘good’ answer, responses must be defended or opposed with material FROM the story or related materials. In other words. Level Two Questions Are Answered Using Facts.

Level 2 Questions might…

- require “Processing” of Information—analyze, synthesize, evaluate, articulate

- require making inferences from the text

- seek understanding from someone who knows more or has larger perspective

- challenge the author (why did you include this but not that, or why was this phrased a certain way?)

Level 2 Questions are often the Meat & Potatoes of Social Studies, and require Level 1 information as support. They seek informed opinions. They are often the stuff we most wish our students could ask, ponder, or answer intelligently.

Come to think of it, they’re the stuff we wish other adults could ask, ponder, or answer intelligently as well.

Examples: Why did the North win the Civil War? Was Lincoln justified in suspending some rights during the war? To what extent was slavery the true cause of the war? How did the North’s war aims change over the course of the war and why?

Level 3 Questions

Deal with ideas beyond the text but which might be prompted by the story / document / whatever. The assigned material is a ‘launching pad’ for these sorts of questions, but responding to them requires going well beyond the original material. In other words, Level Three Questions Have Answers Which Go Beyond The Facts.

Level 3 Questions are useful as…

- “Big Picture” Questions, to make connections

- interest-builders, discussion-starters, and thought-provokers

- ways to get your teacher off topic so you don’t have as much work to do

English Teachers love Level 3 Questions, but in the Social Studies we use them more carefully. Sometimes they’re more appropriate for discussions with your parents, pastors, or best friends. Other times they’re the most important questions there are.

Examples: Is war ever justified? Did Robert E. Lee go to Heaven? What important enough to be worth killing someone over? Is it true Lincoln’s ghost is still haunting the White House? How would the U.S. be different today if the South had won the Civil War?

Sometimes what ‘Level’ a question best fits depends on how much you know – or how much information to which you have access.

Don’t get too hung up on correct categories so much as expanding the sorts of questions students ask. It’s also important they recognize the difference between arguments over the facts, arguments over how to best interpret the facts, and arguments which can’t be resolves using only facts. I mean, how different would our political worlds be if grown-ups could make this distinction once in awhile?

After Level Questions become comfortable, I find it helpful to vary their angles a bit.

“We have an expert visiting us tomorrow to talk about this subject. If we want to make our teacher look good – and we do – we’ll want to be able to ask thoughtful questions of her. So, pretend this subject is brand spankin’ new to you (like you do every time we review something we’ve covered for two weeks) – what other information would you request if you really, really cared? What parts would you want to know more about, if this were genuinely interesting to you? What could you ask that sounds like a question, but is really just you showing off how much you already know and understand? Finally, what could you ask the expert which would prompt involuntary ‘ooooh’s and ‘aaaahhh’s from the rest of us, it’s so thoughtful and relevant?”

Sometimes what ‘Level’ a question best fits depends on how much information you have available or to which you have access. Don’t get too hung up on correct categories so much as stretching the sorts of questions students ask.

I’d never grade my kids specifically on putting questions into the ‘right’ categories. What I do hope to help them think about, however, is the importance of understanding WHAT sort of question is being asked – whether we’re trying to dig around in history or address modern-day dilemmas. So often we think we’re arguing when we’re not even confronting the same sorts of questions.

For example – global warming. To discuss global warming and what, if anything, to do about it, we first need to determine what facts are available. We may argue about the facts, but at least we’ll be wrestling through the same issue. That’s Level One information, and it matters in this discussion.

We also need to figure out the best way to interpret those facts, once agreed upon. What do they mean, why are they what they are, etc.? Again, we may not agree, but at least we’ll be on the same subject. That’s a Level Two conversation.

Finally, what should we do about the facts and our conclusions? Is the issue important? What’s likely to happen if we purseu Course A vs. Course B vs. Course C vs. just ignoring it? That’s a whole other type of conversation to have – a Level Three issue.

Too often, we never get past one person arguing about what changes we need to make while the other hasn’t yet accepted the basic facts being used as support. Or we think we’re debating what the facts mean when in reality we’re debating the nature of reality or the ethics of hoping the supernatural will intervene at some point.

Getting on the same level of discussion in no way guarantees consensus, but it’s an essential element of any meaningful progress towards deeper understanding or potential agreement.

On a smaller, ‘let’s just pass high school first then worry about that other stuff’ scale, Practicing Inquiry helps foster interest. It increases recognition and retention of essential information. It’s foundational to critical thinking. Finally, it’s a critical element of effective reading – Cornell Notes, Dialectic Journals, Annotation, Think-Alouds, etc., all build on the idea that reading is an interaction with the text, and that questions are an essential part of that interaction. But that’s for another page.

RELATED POST: Asking Good Questions (And You Don’t Have To Mean It)

RELATED POST: My Five Big Questions (Essential Questions in History and Social Sciences)

One of the fundamental skills I try to teach my students is to ask good questions. And they don’t have to mean them.

One of the fundamental skills I try to teach my students is to ask good questions. And they don’t have to mean them.

Kids learn while playing, or while caught up in other things. Everything from blocks and unstructured time as a little person through video games or online arguments as a teen – information, good or bad, is created, encountered, or absorbed. This one is so very important and can be crazy effective – but it’s the one most threatened by the Cult of Assessment and our own unwillingness to Defy the Beast.

Kids learn while playing, or while caught up in other things. Everything from blocks and unstructured time as a little person through video games or online arguments as a teen – information, good or bad, is created, encountered, or absorbed. This one is so very important and can be crazy effective – but it’s the one most threatened by the Cult of Assessment and our own unwillingness to Defy the Beast.  We all know the value of parents reading to their children. In a perfect world they take them to museums or musical performances, or travel places promoting conversation and reflection. How many times a day does a parent or sibling overtly attempt to explain a ‘why’ or a ‘how’ to a little kid?

We all know the value of parents reading to their children. In a perfect world they take them to museums or musical performances, or travel places promoting conversation and reflection. How many times a day does a parent or sibling overtly attempt to explain a ‘why’ or a ‘how’ to a little kid? This is the ideal. Those kids who keep wanting to know if they can leave your class to go finish something in Engineering? They tend to get good at engineering. That girl who reads voraciously? She tends to get pretty good at reading. And don’t get me started about young people truly devoted to their choir, marching band, baseball team, or speech & debate.

This is the ideal. Those kids who keep wanting to know if they can leave your class to go finish something in Engineering? They tend to get good at engineering. That girl who reads voraciously? She tends to get pretty good at reading. And don’t get me started about young people truly devoted to their choir, marching band, baseball team, or speech & debate.  I have mixed feelings about this one.

I have mixed feelings about this one.  This may begin from above – parents, or even the school system itself – but often becomes internalized. Either way, this is a stress-driven type of learning with little lasting value.

This may begin from above – parents, or even the school system itself – but often becomes internalized. Either way, this is a stress-driven type of learning with little lasting value. This one is pretty rare if you eliminate the vague terrors in play above. There are a few, however, who are specifically chasing a degree in veterinary medicine, motorcycle repair, or that study abroad opportunity in Monaco. They press on because they know what they want.

This one is pretty rare if you eliminate the vague terrors in play above. There are a few, however, who are specifically chasing a degree in veterinary medicine, motorcycle repair, or that study abroad opportunity in Monaco. They press on because they know what they want.  If you torture them enough, confine them in stale rooms and badger them into compliance…

If you torture them enough, confine them in stale rooms and badger them into compliance…

I’m a fairly narcissistic fellow. I don’t mean to be, it’s just that I’m vain and self-absorbed. At least I have the skills, style, and cojones to make it work for me. I make no apologies; every rose has it’s – oh, are you still here? I hadn’t noticed.

I’m a fairly narcissistic fellow. I don’t mean to be, it’s just that I’m vain and self-absorbed. At least I have the skills, style, and cojones to make it work for me. I make no apologies; every rose has it’s – oh, are you still here? I hadn’t noticed. I’m pretty entertaining, and I have a degree. That should buy me some leeway, yes?

I’m pretty entertaining, and I have a degree. That should buy me some leeway, yes?

Which, by the way, is pretty much what many of you keep telling me about my teaching methods. You know – if I were doing it right, I wouldn’t have to work so hard to coerce and browbeat them… like you’re doing to us?

Which, by the way, is pretty much what many of you keep telling me about my teaching methods. You know – if I were doing it right, I wouldn’t have to work so hard to coerce and browbeat them… like you’re doing to us? When I’m in my classroom, my number one ethical and professional obligation has absolutely nothing to do with your studies, your strategies, and sure as hell not your tests – mandated or not. I’ll certainly consider the input of my department and my building leadership, but even those should take a back seat to what I think and feel and believe will be best for MY kids, today, right now.

When I’m in my classroom, my number one ethical and professional obligation has absolutely nothing to do with your studies, your strategies, and sure as hell not your tests – mandated or not. I’ll certainly consider the input of my department and my building leadership, but even those should take a back seat to what I think and feel and believe will be best for MY kids, today, right now. We’ve become SO comfortable doing things we know are bad for our kids because they’re ‘required’. Maybe we’re afraid, or maybe we simply hide behind what everyone else is doing. Is this such a rewarding career in terms of money, power, and glory, that we’ll sacrificing the very things that made it matter to begin with in order to keep it secure? Must be a helluva extra duty stipend.

We’ve become SO comfortable doing things we know are bad for our kids because they’re ‘required’. Maybe we’re afraid, or maybe we simply hide behind what everyone else is doing. Is this such a rewarding career in terms of money, power, and glory, that we’ll sacrificing the very things that made it matter to begin with in order to keep it secure? Must be a helluva extra duty stipend.