The time between Indian Removal in the 1830s and the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 was a comparatively peaceful – almost prosperous – era for the Five Civilized Tribes (5CT).

Then again, when you have a century of suck on either side of a generation, the bar for “Golden Age” status isn’t particularly high.

Historical Divisions

Despite our tendency to speak of the 5CT as a single entity, they were different tribes composed of individual people – and people never quite fit the generalizations we impose in retrospect. Within each tribe there were mixed-bloods and full-bloods, progressives and conservatives, slave-owners and those with little interest in the practice. Every society has those resistant to change and those quick to rebuke their own culture and the ways of their forebears. Every community has outspoken members and those who simply wish to be left alone. The details may vary, but the same was true of the relocated tribes.

The full-bloods tended to be conservative and – having no desire for cash crops – had little interest in owning slaves. The mixed-bloods tended to speak more English and interact with whites – being family and all – and were more likely to participate in the larger economy. They were far more likely to own slaves, although many did not.

There were exceptions to these generalizations, the most obvious of which was John Ross – a mixed-blood Cherokee who spoke perfect English and had been educated in white-run schools. He was nevertheless considered overall “Chief” of the Cherokee, with his most loyal followers being the older, full-blood members of the tribe.

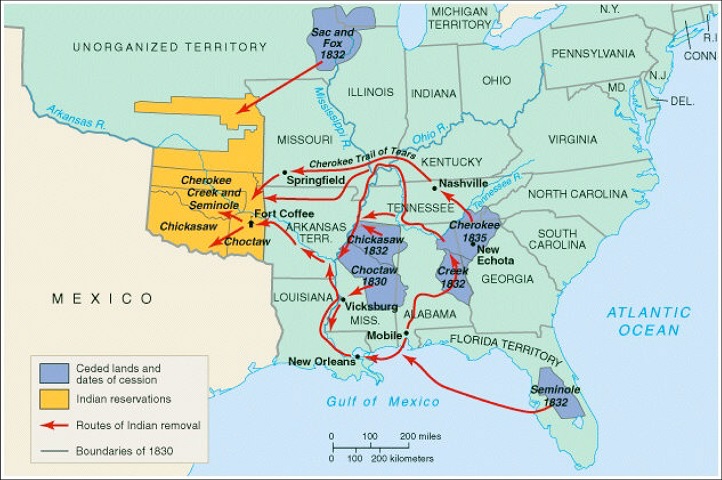

The greatest bitterness, though, came from divisions during Indian Removal. The “Western Cherokee” who’d moved in 1817 had largely embraced the New Echota group, led by Stand Watie and others, upon their arrival in the early 1830s. Those arriving on “Trail of Tears” several years later felt betrayed on the deepest level by those who’d signed the treaties trading away their homelands. Several “Treaty Party” leaders had been assassinated in response.

The Creek experienced a similar split, aggravating issues predating removal. They emigrated to I.T. in waves, beginning with supporters of William McIntosh – another leader executed for his compromises. The Choctaw and Chickasaw had their own struggles with removal, but they stayed largely united during the experience. And the Seminole…

The Seminole are just always hard to pin down in regards to anything. They fought removal and never actually lost, even though many moved. They had “slaves” that weren’t quite actually “slaves” – just… not quite new additions to the tribe. And they…

I’m not really sure what to tell you about the Seminole.

Nevertheless, the Tribes largely rebuilt their worlds in the generation after removal. They established new schools, churches, communities, and in some cases even printed their own newspapers. What would later be named “Oklahoma” was, for a generation, truly a “Land of the Red Man,” although it was largely a “Land of the Black Man” as well. Slavery among the Tribes was still slavery, but it was rarely as brutal or dehumanizing as it was in the South. In some cases it was essentially independent living in exchange for a share of whatever they’d grown or produced.

And then the white people got into a war. With themselves.

Bringing I.T. Into the War

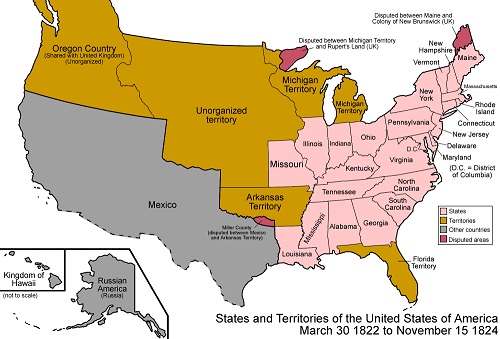

By and large, the 5CT were more than happy to learn that white people were shooting at one another. This was a win-win for them. They weren’t in a geographically essential location – that was part of the reason it was chosen, after all – and had little interest in involving themselves in the white man’s war, at least at first.

Until Albert Pike arrived.

Pike was a Hagrid-looking character, a southerner who’d been born and raised in the north. He began his professional life as a reporter in Arkansas, then a lawyer, and became a strong advocate for various southeastern tribes over the years – minus time in the military fighting in the Mexican-American war. A staunch defender of slavery, he became a loyal Confederate when sides were chosen.

Pike was an ideal choice of ambassador to the 5CT. He was familiar and trusted, and he made compelling arguments why they should support the South in this war.

The Choctaw and Chickasaw signed up with little debate. They were already more like the American South than the remaining tribes, more agricultural and owning more slaves than the rest. The remaining tribes split over the issue – often along lines lingering from previous disputes. While officially all Five of the “Civilized Tribes” joined the Confederacy, substantial minorities of the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole fought for the Union. That whole “brother against brother” thing was brutal for everyone involved, but in some ways it hurt the 5CT most.

At first gander, the preponderance of support for the South seems surprising – the Tribes had been ejected from the south, and harassed by southern states prior to that. But that’s not how most viewed the situation. It’s almost certainly not how Pike framed it.

So why join the Confederacy?

First and foremost, the Tribes owned slaves. Most individuals did not, but that was true of the American South as well. The culture supported it, and the same folks who tended to be fiscally ambitious enough to need slaves tended to be politically active as well. Leaders who weren’t slave-owners weren’t exactly abolitionists either, so there was little in the way of a “balancing viewpoint.” There were pro-slavery voices, and there were those who had other concerns instead.

Second, Indian Removal was remembered as a betrayal of the “Great White Father” in Washington, D.C. – not so much as a conflict with individual states. Their treaties had been made with federal power, and either enforced or broken by federal soldiers taking federal orders. It didn’t help that the same federal government wasn’t particularly consistent following through with promised supplies and other resources.

Third, the Union soldiers who’d been stationed in and around I.T. as part of the Tribes’ latest treaties with the U.S. had been pulled and reassigned as soon as it became clear war was coming. It’s not that the Tribes were such great buddies with the soldiers, but plenty of Plains Indians who hadn’t earned the sobriquet “Civilized” were still active in the region, and the U.S. military provided a decent buffer against their brutality.

Fourth, the 5CT had more in common with Americans in the south than they did those in the north. Friends or not, many Amerindians practiced agriculture – none owned factories. Many lived on farms or in what white culture would see as ‘semi-rural’ settings – none lived in tenements. Many relied on themselves and their traditions to guide them – few saw value in reform movements, technological progress, or ‘Great Awakenings.’ While the federal government had let them down repeatedly, the largely sympathetic ‘Indian Agents’ with whom they dealt and through whom they processed white society were mostly from the south.

Finally, with no way to predict the outcome of the conflict, the South offered them a better deal. The North – in the form of the federal government – had already lost whatever credibility they might have had, while the South promised the Tribes more protections, greater autonomy, and all those “states’ rights” kinds of things that would become so prominently recalled after the war. The South also promised to assume commitments made under previous treaties with the U.S., including the annuities the North had ceased as soon as distracted by conflict with the South. The North and their President Lincoln, meanwhile, were aggressively promoting westward expansion. If you don’t see an immediate problem for the tribes in that, look at any map.

So, despite the splits described previously, the Confederacy it was.

It wasn’t going to work out as well as they’d hoped.

Red, White, and War

Like anything in history – especially when that anything is a war – the depths into one might plunge are limitless. I generally limit myself to four key events when covering the Civil War in I.T.

1. Opothleyahola

Opothleyahola – or “Opie” as we end up calling him in class if we ever wish to get past the ongoing struggle to pronounce his name comfortably – was a Creek leader who’d been fighting the federal government and white encroachment as far back as the War of 1812. He was a wealthy landowner, a Baptist, and a Freemason (all the cool kids were back then).

By the time the Civil War came to I.T., Opie was so over white guys and their talent for disrupting and diminishing the Tribes. He was unwilling to join the Confederacy, but no fan of the Union. Others of similar mind found their way to his plantation in fits and starts, and he soon found himself the default leader of several thousand Creek, Chickasaw, Seminole – even some runaway slaves and other miscellany. The unifying characteristic was their desire to stay out of this war.

Opie received permission from President Lincoln to lead this amalgam to Kansas. There were fewer than 2,000 warriors, but they hoped to avoid conflict with either side. The majority of their band were women, children, old men, and livestock – little threat to anyone.

It didn’t work out that way, and troops were sent by the Confederacy to persuade them to change their mind. The first “Red on Red violence” of the war took place against a group trying to do what they’d all wanted to do initially – just stay out of it.

Opothleyahola began his trek with somewhere in the area of 9,000 wanderers, and arrived in Kansas with less than 2,000 by most estimates. War, winter, hunger, and disease did their damage just as they had a generation before. The Union encampment there was completely unprepared for even these diminished numbers, and were of little help. After doing what he could to secure assistance for his people, Opie led those still able to fight back into I.T. to war against the Confederacy. He’d die in one of the Kansas refugee camps before the war was over.

2. The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 1862)

Early 1962 was not going well for the Confederacy in the Western Theater. Ulysses S. Grant was making a name for himself and captured Ft. Henry and Ft. Donelson along the Mississippi River, nearly cutting the South in two and enabling the Union to squeeze the secesh into submission. The Confederacy saw St. Louis – right there where the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers converge – as the key to reversing this trend.

General Albert Pike was called to I.T. to take command of Amerindian troops there, primarily Cherokee. They were poorly supplied and barely organized, and many weren’t enthused about supporting the Confederacy. Nevertheless, Pike led them into Arkansas (despite initial guarantees they would fight only to defend I.T.) where they joined in the Battle of Pea Ridge in March of 1862.

The Battle of Pea Ridge could fill an entire History Channel special. For our purposes, there are three things worth remembering.

First, this was the first time Cherokee troops fought on this scale in a white man’s battle. The Amerindian ways of fighting were dramatically different than white guys’ methods – the goals, the strategies, and especially the command structure. The U.S. and Confederate militaries were organized along a strict hierarchy. While not as loosely organized as the Plains Tribes, the Cherokee simply didn’t work that way – not socially, not politically, and certainly not militarily. By white military standards, they were a mess.

Second, most of Pike’s Amerindian troops fought with bows and arrows, or with tomahawks. That’s what they had, and what they knew how to use proficiently. Unfortunately, against somewhat trained soldiers with guns, they were of limited impact in this situation.

Third, and most importantly, the Cherokee were accused of scalping some of their Union victims. While this apparently did actually happen, the details are a bit vague. What is certain is that knowledge of this spread widely and quickly, growing and distorting in ways you wouldn’t think possible before Facebook. White soldiers on both sides were horrified – that is NOT how civilized men behaved! Kill and maim one another PROPERLY!

Pike was outraged at the treatment of the Amerindian troops in his command and excoriated in press and popular opinion for “allowing” scalping and general savagery to take place. He was the only white commander on either side to so vigorously advocate for them, albeit unsuccessfully, and he paid the social and political price for doing so. His Cherokee withdrew to I.T. where they were left unsupported and unprotected.

Oh, and by the way – the Union won.

3. The Weer Expedition

The Union had two goals for I.T. in 1862 – push back against Confederate advances in the region, and restore the pro-Union Amerindian refugees to their homes. Seemed simple enough, and the goals certainly complimented one another.

Colonel William Weer was appointed to command several white and two “Indian Regiments” along with supporting artillery. Pike was so annoyed at this point he refused to even lead the Confederate opposition, although Weer would face sporadic resistance along the way, especially from Cherokee forces led by Stand Watie.

They got as far as Locust Grove, about halfway between modern Tulsa and the Arkansas border. There they defeated some Missouri rebels and captured their supplies, but decided to wait for their own supply train to catch up as well. (It’s not like an army can forage its way through Oklahoma – if the land were that rich, we’d never have sent the Indians here.)

During the wait, Union forces fell apart all on their own, without the Secesh having to do much to help. It was July by then, and hot. Really hot. Too hot. Supplies were running low again, and soldiers with nothing to do and no real fortifications had plenty of time to worry about Confederate counterstrikes. To top it all off, Weer was apparently quite a drinker. Like, crazy useless drunk pretty much full-time by this point. Underlings swore he’d genuinely lost his mind as a result and was no longer fit to lead even when he was sober.

His second-in-command arrested him and took over, ordering a withdrawal of the white troops but leaving the Amerindians behind without orders. Had the Confederates been in a position to take advantage of this, it could have shifted the balance of power in I.T. back in their favor. But they weren’t, so it didn’t. Those locals who’d been “resettled” were nevertheless nervous about the withdrawal and complete lack of a Union strategy, and most began heading to Kansas yet again, where they spent another winter in refugee camps, suffering from cold, hunger, and disease.

Overall, the expedition was not considered a huge success.

4. The Battle of Honey Springs

July of 1863 was arguably THE turning point of the entire Civil War. In the Eastern Theater, Lee’s second and final effort to bring the war to the North was thwarted at the three-day Battle of Gettysburg. In the Western Theater, the nearly two-month-long Siege of Vicksburg perpetrated by U.S. Grant finally ended, securing control of the Mississippi River for the Union. The ‘Anaconda Plan’ was complete (although Winfield Scott had since passed away and thus missed his opportunity to gloat).

In the same month, the Massachusetts 54th Infantry – the first substantial use of Black troops in the war – made their dramatic but costly charge on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. While a strategic defeat, the performance of the 54th settled for the remainder of the war the question of whether or not Black troops should be allowed to fight as relative equals. Finally, in Indian Territory, the Battle of Honey Springs – the “Gettysburg of the West” – secured Union control of I.T. for the remainder of the war.

OK, no one outside of Oklahoma teaches Honey Springs as the “Gettysburg of the West.” Most people inside of Oklahoma don’t either. But when you’re Oklahoma, you grab on to whatever validation you can get, kids.

Did you know Carrie Underwood is from here? And several astronauts? We matter! Shut up!

A year after the Weer debacle, Union forces had successfully occupied Fort Gibson and were maintaining a limited military presence in I.T. once again. Being how it was a war and all, the Confederacy hoped to drive them out, and assembled about twenty miles away at Honey Springs Depot. From there they sent out cavalry to harass and attack Union supply lines and take advantage of whatever other opportunities presented themselves without fully engaging.

Honey Springs had already become an important location to the Secesh in Indian Territory. Troops came there for medical attention, to get whatever limited supplies were available, etc. It was essentially “home base” for the South. General Douglas Cooper, a veteran of the Mexican-American War and former Indian Agent to the Choctaw and Chickasaw, was in command.

It was hard to keep secrets in wartime, and Colonel Phillips, in command of Union forces at Fort Gibson, was well-aware an attack was imminent. Rather than wait for the Confederates to receive reinforcements, Phillips decided to take the war to them. He was joined by Major General James Blunt from Kansas, who brought additional troops and artillery, and who would thenceforth be in charge.

As mentioned earlier, war aficionados can stay all tingly for days over the details of this or that battle, strategy, or new bridle design. Here are the key points I consider worth remembering about Honey Springs – other than that “Gettysburg of the West” thing, I mean.

First, it was arguably the most racially diverse battle of the Civil War. Blunts troops were a mixture of white, Black, and Amerindian forces, while Cooper’s troops were mostly Amerindian with a few white regiments. Whites were in the minority on both sides.

Second, it rained. In addition to the general unpleasantness of marching and fighting over wet ground, the Confederates discovered their cheap gunpowder had absorbed too much moisture and wouldn’t fire. At the risk of getting all technical, it turns out it’s hard to win battles when you can’t shoot the other guy.

Third, the battle’s outcome turned on an error – a beneficial blunder, as it were. After several hours of intense battle, including serious cannon action, Blunt (Union) orders the First Kansas Colored Voluntary Infantry Regiment to capture some Confederate artillery which had been giving them trouble. Confederate forces had a decisive advantage in terms of manpower, but the Union had more toys – and they didn’t appreciate the South challenging them when it came to things that go ‘boom.’

As the First Kansas Colored pressed towards their goal, a regiment of Union Amerindian troops unintentionally moved between them and Confederate forces. As they realized their error and withdrew, Confederate leaders assumed the Union was falling back in general, and enthusiastically ordered pursuit.

They ran right into the First Kansas and their fancy Springfield rifles, and bad things ensued. A mix of Black, White, and Red troops drove the Southerners back, but in all the chaos failed to capture those cannons. The Confederates tried to torch Honey Springs in order to keep the goodies there from falling into Union hands, but Northern soldiers managed to extinguish most of the fires and everyone had extra bacon and sorghum biscuits for a few days.

The First Kansas Colored Volunteers earned high praise for their bravery and composure throughout the battle, news of which made it into the papers right as the Massachusetts 54th was proving a similar point much further east.

Most of the fighting in I.T. after Honey Springs was hit-and-run, guerilla warfare. Stand Watie and other Amerindian leaders couldn’t turn the tide of the war on their own, but they did make things mighty inconvenient for the Union for its duration. Watie was the last Confederate General to surrender when the war eventually ended.

Aftermath

The damage to I.T. as a result of the Civil War is difficult to overstate. Like much of the south, the loss of property and destruction of land was dwarfed only by the loss of life.

As people began to return to their homes rebuild their lives, a Radical Republican Congress was trying to build on this victory to make some major changes across the country. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were soon passed, ending slavery, giving Freedmen the right to vote, and declaring for the first time ever that a citizen is a citizen is a citizen, and that neither state nor nation can presume otherwise – at least according to written law.

The South would resist these changes for another century, but there was one group already so beaten and misused by the U.S. that they were in no position to make a similar stand. Besides, they’d officially chosen the wrong side in the recent war.

The U.S. Congress was about to impose their will yet again on the citizens of Indian Territory, in ways they were unable to do anywhere else. Reconstruction is coming. Hard.

NOTE: A more easily printable version of this post is available on “Well, OK Then…”

If for some strange reason you’ve not already read Part One several times already and copied favorite bits onto sticky notes to post around your bedroom and kitchen, I there waxed adoring over Helen Churchill Candee and her first extensive article about life in Oklahoma Territory, published in The Forum, June 1898. She wrote at least three other articles about O.T. in the time she lived there, all very positive towards her temporary homeland but varied in style and focus.

If for some strange reason you’ve not already read Part One several times already and copied favorite bits onto sticky notes to post around your bedroom and kitchen, I there waxed adoring over Helen Churchill Candee and her first extensive article about life in Oklahoma Territory, published in The Forum, June 1898. She wrote at least three other articles about O.T. in the time she lived there, all very positive towards her temporary homeland but varied in style and focus.

Helen Churchill Candee came to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory (O.T.) in the mid-1890s, primarily drawn by its

Helen Churchill Candee came to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory (O.T.) in the mid-1890s, primarily drawn by its  Oklahoma is trying hard to outbid all of its neighbors in the matter of granting easy and quick divorce. An attorney at Kingfisher, in that Territory, has issued a circular which points out that the statutes of Oklahoma specify no fewer than “ten separate and distinct causes, for any one or more of which a divorce may be obtained,” including that all-embracing term, “gross neglect of duty”…

Oklahoma is trying hard to outbid all of its neighbors in the matter of granting easy and quick divorce. An attorney at Kingfisher, in that Territory, has issued a circular which points out that the statutes of Oklahoma specify no fewer than “ten separate and distinct causes, for any one or more of which a divorce may be obtained,” including that all-embracing term, “gross neglect of duty”…

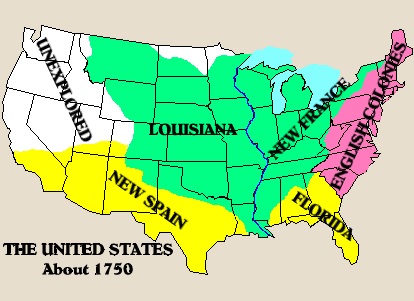

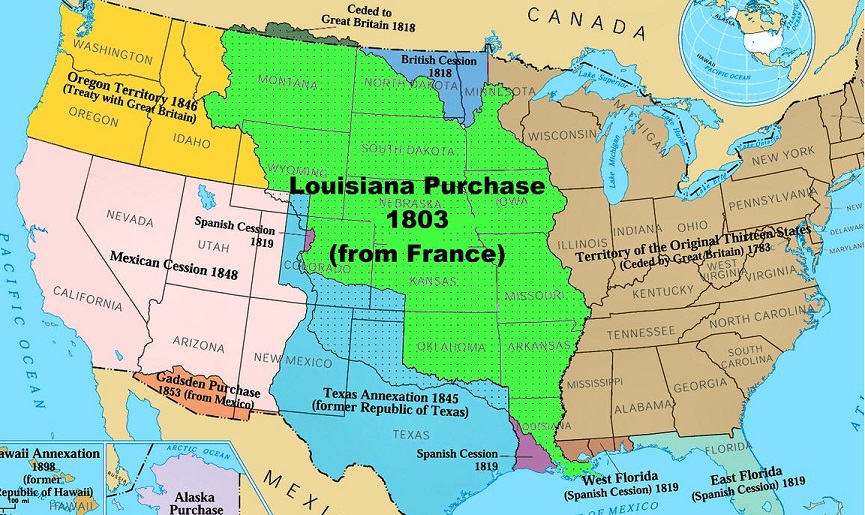

The first European nation to lay claim to what is now Oklahoma was Spain, via wanderings sent forth from New Spain – what today is Mexico.

The first European nation to lay claim to what is now Oklahoma was Spain, via wanderings sent forth from New Spain – what today is Mexico.  In any case, the Treaty of Paris (1763) transferred proud ownership of all this flat, red dirt to the British, despite a secret agreement handing it over to Spain only a year before. It says something about the status of pre-settlement Oklahoma that Spain didn’t even fuss over this double-dealing; their primary concern involved other territories included in that exchange.

In any case, the Treaty of Paris (1763) transferred proud ownership of all this flat, red dirt to the British, despite a secret agreement handing it over to Spain only a year before. It says something about the status of pre-settlement Oklahoma that Spain didn’t even fuss over this double-dealing; their primary concern involved other territories included in that exchange.  Fine. We’ll waive our *mumble* wheat for someone *murmur* can appreciate *grouse* land we belong to is grandma’s crusty *obsenitiesandbitterness*.

Fine. We’ll waive our *mumble* wheat for someone *murmur* can appreciate *grouse* land we belong to is grandma’s crusty *obsenitiesandbitterness*. But the U.S. found it necessary to violate a number of its own fundamental values and laws in order to kick FIVE distinct nations out of an area roughly the size of THREE entire states. They did so at enormous cost to themselves and unforgivable loss of life to those removed. This was driven by something bigger than gold, something fundamental to an expanding nation.

But the U.S. found it necessary to violate a number of its own fundamental values and laws in order to kick FIVE distinct nations out of an area roughly the size of THREE entire states. They did so at enormous cost to themselves and unforgivable loss of life to those removed. This was driven by something bigger than gold, something fundamental to an expanding nation.  There we go – the “besides, it’s good for them” defense. We used a variation of this to justify slavery, you may recall – saving all those crazy Africans from their ooga-booga religions and cannibalism and such, freeing them up to play banjos around the fire and partake of the finest Christian civilization.

There we go – the “besides, it’s good for them” defense. We used a variation of this to justify slavery, you may recall – saving all those crazy Africans from their ooga-booga religions and cannibalism and such, freeing them up to play banjos around the fire and partake of the finest Christian civilization.  Jackson may be overdoing it a bit, even by the standards of the day. His primary purpose was most likely not to convert anyone adamantly opposed, but to assuage any guilt on the part of those already looking for an excuse. That’s why we talk about “audience” and “reason” when we do document analysis, kids – dead white guys can be sneaky.

Jackson may be overdoing it a bit, even by the standards of the day. His primary purpose was most likely not to convert anyone adamantly opposed, but to assuage any guilt on the part of those already looking for an excuse. That’s why we talk about “audience” and “reason” when we do document analysis, kids – dead white guys can be sneaky.