Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About the “Mourning Wars”

Three Big Things:

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.

2. One of the primary goals of this sort of warfare was to replace lost loved ones with captives taken from enemy tribes.

3. Captives not used as faux family members were generally executed, sometimes after long ritual torture. It was… harsh.

Eastern Amerindian Warfare

The Amerindians whom northern American colonists were most likely to encounter weren’t necessarily more peaceful than Europeans, but the type of warfare in which they most often engaged and the goals of such hostilities were substantially different.

East of the Great Plains, all the way to the Eastern Seaboard, numerous tribes (the Iroquois are the best remembered, but there were dozens of others) were locked into perpetual retaliation, each act of aggression requiring response. Every death of a loved one or tribal member demanded retribution; each raid required a counter. These weren’t the sort of extended, large-scale undertakings common in European conflicts. Tribes struck quickly, inflicted what damage they could, often taking captives and leaving behind a few casualties, then retreated to their own settlements.

There was little interest in taking over your enemy’s entire land, if such a thing were even possible. What would you do with it? Besides, while the thirst for requital was no doubt genuine, warfare served multiple other roles – a uniting cause for the communities involved, a sense of justice or closure for those mourning loved ones lost to previous conflicts, a road to honor and status for young warriors seeking to establish their manhood, and – depending on the tribe – a supply of victims for whatever ritual tortures and sacrifice were thought to please the gods or placate the beyond.

What’s perhaps most foreign to the western worldview, however, is what else they provided – substitutes for family members taken or killed by the tribe now under attack.

Like, literally.

The “Mourning Wars”

These “mourning wars” – often initiated at the behest of tribal matriarchs still grieving the loss of sons, brothers, or husbands – were particularly focused on taking captives from enemy tribes. Some of these captives would be tortured, many killed, but a significant number would be inserted into the roles left open by previous raids or other misfortune. This was, in fact, often the central motivator – not a certain number of enemy deaths, and certainly not captured or destroyed villages, but warm bodies of roughly the same age and potential of those lost. If they looked similar, well… bonus!

There was thus no shame in avoiding open confrontation whenever possible, as the resulting death toll was counterproductive to the purposes of the attack. Ambushes were far preferable, as were relatively low risk hit-n-runs. While more than willing to face suffering or death, warriors weren’t exactly seeking it out.

The glory of martial self-sacrifice is a culturally constructed phenomenon – it’s not inherent to all times and places. Our veneration for violent death may be laudable, but it’s not universal. To quote the fictional George S. Patton in his ‘Ode to Enormous Flags’… “No dumb bastard ever won a war by going out and dying for his country. He won it by making some other dumb bastard die for his country.”

All these years later and that bit still brings a tear.

This aversion to violent death wasn’t mere cowardice. It was largely spiritual – many tribal belief systems consigned victims of such hostility to wander the earth eternally seeking vengeance, or otherwise unable to find peace. It was intensely practical as well – these were relatively small tribal units in which every member played an essential role. Even should a warrior or two wish to seek status via bravado or reckless tactics, doing so would have been irresponsible and borderline disloyal to the community who would lose his presence and his support as a result.

Which brings us back to the captives – the ‘replacements’, if you will.

Being taken captive could be terrifying, even if you had some idea what to expect. Anyone perceived as potentially more trouble than they were worth – women or children of the wrong age or build, or warriors capable of fighting back even after captured – were more often than not scalped and killed on the spot. Most, though, were bound and led back to the village, where they would be forced to walk among the tribe while being hit, insulted, and otherwise abused. Sometimes they were cut or burned. It sounds nasty.

Captured warriors were likely to face extended torture and public humiliation – often in retribution for similar offenses by their own tribe. They were expected to endure such suffering stoically, which most apparently did, although it’s difficult to discern too many details from surviving records – most of which come down to us through the occasional white folk involved for one reason or another, their very presence no doubt altering the experience. These same accounts suggest it was common to eat the condemned afterwards, which makes a certain amount of symbolic sense, but which might also be the sort of thing added to further ‘other’-ize or demonize native populations.

Surviving women and children were assigned to families based on their general age, appearance, or skill set, as were young men who were found to be particularly handsome or potentially useful. They were given the name of the person they were intended to replace, along with any title or position that person had held, and over time generally ‘became’ that person – to the point of becoming a very real part of their new family, and eventually loyal to their adopted tribe.

This apparently provided a sort of comfort to mourning family members, along with whatever sense of justice or restitution they craved, and the community was reinforced in both numbers and spirit as a result. However foreign it may seem to western norms, it was practical and effective. No one wanted to be on the losing end of these bargains, but there’s no indication that anyone involved protested or found a problem with the system itself. Over time, it maintained balance and numbers among the various tribes – unlike, say, European style warfare, whose entire purpose was to destroy and eliminate the enemy, whatever the cost on both sides.

Upsetting Balance

It’s most likely with this guiding balance in mind that tribal leaders discouraged young men from taking matters into their own hands and initiating raids on their own. While strict hierarchical rule was not in the nature of most Amerindian cultures, community members generally deferred to the wisdom and wishes of those who’d proved themselves capable and wise. In return, leadership avoided anything approaching dictatorial control, steering the community instead by example and clearheaded thinking.

Through subtle combinations of gifts or other gestures of goodwill, peace could be established and maintained with some – if not all – neighboring tribes. For tribes who developed trade with one another, peace was not only desirable but likely. And if there were even distant kinship connections, well… besties! Conversely, groups with particularly fierce reputations were able to maintain a degree of peace and security via fear – they simply weren’t worth tangling with. Losses and suffering would outweigh gains and glory.

Despite the seemingly brutal and unforgiving nature of the “mourning wars,” there were rules – however informal. Then, as now, young men out to establish a reputation for themselves did not always defer to the wisdom of their elders. Among the eastern tribes of pre-colonial and colonial times, this was especially unfortunate since the overarching purpose of warfare was to stabilize and preserve one’s own people; unprovoked or reckless raids set off a chain of reprisals which of course did quite the opposite.

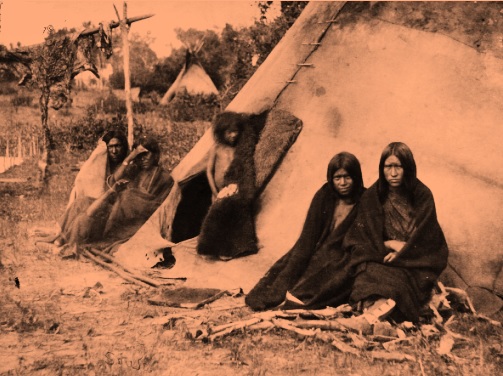

As with so many other elements of Native American culture, the arrival of white folks, their weaponry, their land hunger, and of course their arsenal of diseases, completely overturned whatever “stability” had been maintained by these “mourning wars.” Efforts to replace those lost to smallpox or other epidemics quickly destroyed weaker communities, while guns and other technology spread unevenly through the mix, making previous realities unsustainable.

You Wanna Sound REALLY Smart? {Extra Stuff}

If you need to sound thoughtful about the “mourning wars”, consider some comparisons to other systems of maintaining population or community balance which also strike modern western readers as a mite odd.

There are numerous examples of polygamous cultures – from the Latter Day Saints in the 19th century U.S. all the way back to the Old Testament Jews (think King David and such). Multiple wives was one way to promote rapid reproduction and maintain population, especially for marginalized or otherwise endangered groups. It’s a great example of morality being shaped by need and circumstance.

The age at which young women are considered marriable (and thus, appropriate sexual partners) has varied widely from culture to culture over the centuries. The shorter the lifespan and harder the living, the younger the appropriate age tends to be.

One of the most interesting customs related to reproduction was described by Marco Polo as he traveled across Asia. High in the mountains he encountered isolated communities in which he was welcomed into every home and encouraged to stay as long as he liked – in the daughter’s room, in the sister’s room, even in the master bedroom while the husband was suddenly called away on business. Polo feigns moral shock on behalf of his reading audience while exploiting the salaciousness for a page or two before explaining that because these communities were so isolated, they relied on random travelers to inject much-needed variety into their gene pools. Western morality could very well have crippled or destroyed them within a few generations.

The other direction you might consider if called upon to discuss the “mourning wars” is to focus on the contrast between Amerindian warfare and “white guy” warfare. The long traditions of independence – even during battle – among the majority of tribes worked poorly against strict hierarchical military structure of the west. Generations of limited warfare prioritizing glory or capture or territory ran into a military tradition of capture and destroy, with predictable results.

I may have mentioned how giddy I was to come across a wonderful piece by Helen Churchill Condee in Harper’s Weekly, from way back on February 23, 1901. When you combine insight, knowledge, and pithy writing, you have my heart forever.

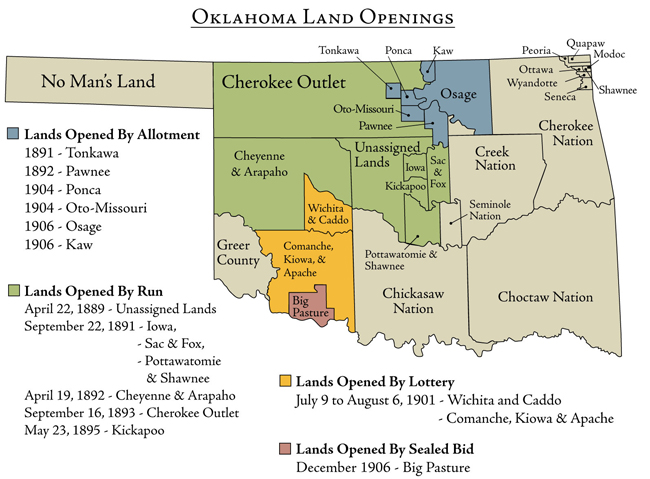

I may have mentioned how giddy I was to come across a wonderful piece by Helen Churchill Condee in Harper’s Weekly, from way back on February 23, 1901. When you combine insight, knowledge, and pithy writing, you have my heart forever. Candee moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, for several years, writing regularly for periodicals back east. It was around this time she published her first two books – How Women May Earn A Living and An Oklahoma Romance. The first became a landmark in women’s literature (a subject for another time) and the second – her only work of fiction out of the many successful books she’d continue to write – helped publicize and glorify life in the recently opened territory.

Candee moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, for several years, writing regularly for periodicals back east. It was around this time she published her first two books – How Women May Earn A Living and An Oklahoma Romance. The first became a landmark in women’s literature (a subject for another time) and the second – her only work of fiction out of the many successful books she’d continue to write – helped publicize and glorify life in the recently opened territory.

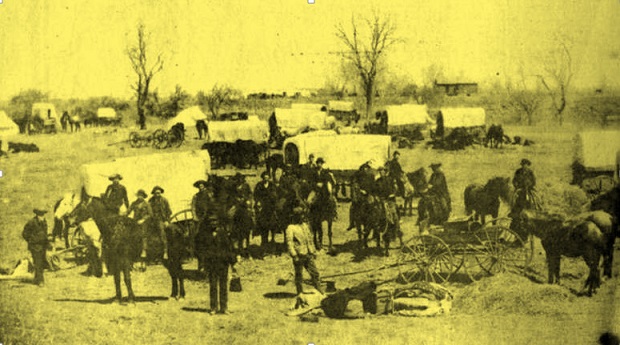

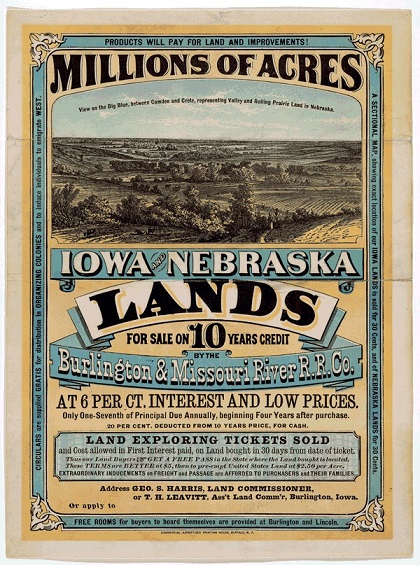

At that moment, it was still all about land – farming, growing, raising, living land. And this was it. Everything else was pretty much taken. The bar was closing and the men outnumbered the women 3 to 1. Time to make your play.

At that moment, it was still all about land – farming, growing, raising, living land. And this was it. Everything else was pretty much taken. The bar was closing and the men outnumbered the women 3 to 1. Time to make your play.  The allotment size was consistent with the Homestead Act from way back in 1862, signed by Lincoln during the Civil War. This was considered a sufficient spread to allow a homestead and plenty of planting land. A free man working without modern equipment would be unlikely to cultivate more than this productively.

The allotment size was consistent with the Homestead Act from way back in 1862, signed by Lincoln during the Civil War. This was considered a sufficient spread to allow a homestead and plenty of planting land. A free man working without modern equipment would be unlikely to cultivate more than this productively.  How many others in that generation and prior had taken their shots, staked their claims, virtually everywhere else in the West? Those waiting now were the also-rans, the coulda-beens, desperate for one last chance at stepping into the role of Yeoman Farmer in the most democratic manifestation of the ideal. Redemption? Maybe so.

How many others in that generation and prior had taken their shots, staked their claims, virtually everywhere else in the West? Those waiting now were the also-rans, the coulda-beens, desperate for one last chance at stepping into the role of Yeoman Farmer in the most democratic manifestation of the ideal. Redemption? Maybe so.