NOTE: This is an excerpt from “Have To” History: A Wall of Education. In the 50+ years since this decision was issued, the “Lemon Test” has been clarified, narrowed, reinforced, and finally all but discarded by an evolving Supreme Court. (The recent decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton references it several dozen times – mostly negatively.)

That’s unfortunate, in my opinion, because it was for several decades one of the most straightforward and balanced approaches to avoiding “establishment” problems without overly hindering “free exercise.” The case is still important, however – not only because of the issues involved and the “test” which resulted, but for the erudite arguments and genuine efforts to remain pragmatic without sacrificing fundamental liberties on either side. The majority opinion by Chief Justice Warren Burger is one of the best on this topic in the entire history of the Court.

Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971): Because Nuns Are Gonna Be Nuns

Three Big Things:

1. Lemon v. Kurtzman addressed the question of whether state financial support for the teaching of secular subjects within religious schools violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. (It did.)

2. Direct State support of religious schools was determined to be unconstitutional because faculty, unlike textbooks or equipment, cannot be reasonably expected to turn their faith “on” or “off” based on the subject they’re assigned that period. Religious schools are by their nature religious, even when teaching non-religious subjects.

3. This case is best known for establishing the “Lemon Test,” a three-part checklist often used to determine whether or not a given government action violates church-state separation.

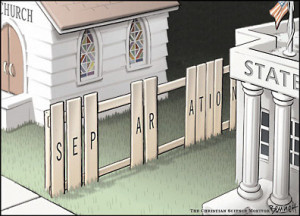

Background: A Wall of Separation

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court decided it was perfectly acceptable for the state to reimburse parents for transportation costs of getting their children to school, whether public or private, sectarian or secular.

A decade and a half later, in Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court made clear that the state could not require – or even promote – prayer in public schools as part of the school day, no matter how generic the prayer. This was followed closely by Abington v. Schempp (1963) in which the same was applied to the reading of Bible verses or the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer.

In Board of Education v. Allen (1968), the court determined it was perfectly acceptable for New York to provide textbooks free of charge to all secondary students (grades 7–12), including those in private schools. Much like the busses in Everson, textbooks were considered of general benefit to all students. For the government to make it more difficult for students in religious schools to learn Algebra or Science would, in fact, violate the “free exercise” clause.

In none of these cases was the goal to drive faith out of public education. The Court’s concern, rather, was to prevent either the power of government or the foibles of politicians from unduly interfering in man’s reach for the Almighty. Or, at least, that was how it interpreted the Framers’ concerns as expressed in the First Amendment, applicable to the states via the Fourteenth – a judicial philosophy known as “incorporation.”

The Abington decision included a little checklist by which interested parties could determine whether or not something violated the “wall of separation” established by the First Amendment. That checklist was refined less than a decade later when the Court heard Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971).

Give Me That Part-Time Religion

As of 1969, both Pennsylvania and Rhode Island had plethoras of private schools, the vast majority of which were Roman Catholic. Then, as now, most private schools operated on tight budgets. The average per-pupil expenditure was lower than public schools in the same area – even when numbers were adjusted to reflect only “secular education.” In other words, students in many private Catholic schools weren’t benefitting from the same resources as kids in public schools, even when learning science, math, or other non-religious subjects.

Both states passed legislation to provide supplemental support for these private schools, as long as the extra funds were used only for the teaching of secular subjects and buying non-religious materials. In some cases, this included help with teacher salaries. There were parents in both states, however, who complained that this diverted resources from public schools to support sectarian institutions, thus violating the First Amendment.

It presented an interesting dilemma: Was modest financial assistance for a sectarian school more like including a little prayer and some Bible verses in Engel or Abington, or supplying bus fare and textbooks in Everson or Allen? Does state assistance constitute “establishment,” or would eliminating that assistance violate “free exercise”?

Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York (1970)

Only a year before, the Court had addressed a similar dilemma in Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York. It wasn’t a public school case, but many of the issues were comparable.

The city of New York had granted property tax exemptions to religious organizations when the property in question was used exclusively for religious worship – putting them in the same general category as schools or charities, who claimed similar tax exemptions on their properties. Some property owners who did pay taxes argued this violated the Establishment Clause.

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good by allowing the same tax benefits as any non-religious non-profit serving a similar function. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.

The majority opinion in Walz, written by Chief Justice Warren Burger, cited a number of prior cases by way of illumination – many of them involving public schools. In turn, Walz would be cited in subsequent school-related church-state cases. Several of his more salient points, in fact, could have just as easily been prompted by Engel, Allen or Lemon:

The Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment are not the most precisely drawn portions of the Constitution. The sweep of the absolute prohibitions in the Religion Clauses may have been calculated, but the purpose was to state an objective, not to write a statute…

In other words, that Separation of Church and State thing is an ideal, a goal – not a clear set of rules for every situation.

The Court has struggled to find a neutral course between the two Religion Clauses, both of which are cast in absolute terms, and either of which, if expanded to a logical extreme, would tend to clash with the other…

The Court thus recognized that the best application of First Amendment values wasn’t necessarily obvious in each and every case. Sometimes, protecting the rights of everyone concerned is an imperfect balancing act.

The First Amendment, however, does not say that, in every and all respects, there shall be a separation of Church and State. We sponsor an attitude on the part of government that shows no partiality to any one group, and that lets each flourish according to the zeal of its adherents and the appeal of its dogma…

The course of constitutional neutrality in this area cannot be an absolutely straight line; rigidity could well defeat the basic purpose of these provisions, which is to insure that no religion be sponsored or favored, none commanded, and none inhibited…

Justice Burger was suggesting that the best way to remain faithful to the ideal is to remain flexible with the specifics. Pragmatic, yet poetic.

Short of those expressly proscribed governmental acts, there is room for play in the joints productive of a benevolent neutrality which will permit religious exercise to exist without sponsorship and without interference…

Once one successfully navigates “there is room for play in the joints productive of a benevolent neutrality,” this is either a doggedly practical or maddeningly evasive approach. Burger seems to be confessing a certain degree of “figuring it out as we go” by the Court – although in this case, that “figuring” includes fifteen pages of detailed analysis and historical background.

The Lemon Decision

As with Walz, Chief Justice Burger wrote the majority opinion. He again acknowledged the difficulty of neither promoting nor hindering religion, but this time laid out what would become known as “The Lemon Test” – one of the most enduring bits of jurisprudence from the Burger Court. (Also, it’s fun to say “Burger Court” and mean something totally for real and serious.)

Every analysis in this area must begin with consideration of the cumulative criteria developed by the Court over many years. Three such tests may be gleaned from our cases. First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion… finally, the statute must not foster “an excessive government entanglement with religion” …

Or, rephrased to apply more specifically to the case at hand:

In order to determine whether the government entanglement with religion is excessive, we must examine the character and purposes of the institutions that are benefited, the nature of the aid that the State provides, and the resulting relationship between the government and the religious authority…

Justice Burger went on to explain how very clearly religious these private schools were. Most were located on the same grounds or in close proximity to associated churches. Religious symbols pervaded each campus. Roughly two-thirds of the instructors were nuns. To cap it all off, the Catholic faith was pretty explicit about the fact that a large part of the reason they had parochial schools to begin with was to spread their faith. So were they religious?

Well… yeah.

But what about Allen a few years prior?

In Allen, the Court refused to make assumptions, on a meager record, about the religious content of the textbooks that the State would be asked to provide. We cannot, however, refuse here to recognize that teachers have a substantially different ideological character from books.

Good to know someone realized that. If only he’d added “or online coursework.”

In terms of potential for involving some aspect of faith or morals in secular subjects, a textbook’s content is ascertainable, but a teacher’s handling of a subject is not. We cannot ignore the danger that a teacher under religious control and discipline poses to the separation of the religious from the purely secular aspects of pre-college education. The conflict of functions inheres in the situation.

Despite several more pages of explanation, that pretty much sums it up. The balance between pushing religion and punishing it is a tricky one, yes – but in this specific situation, the Court decided, the state had some seriously conflicted inhering going on.

It wasn’t malicious. It simply wasn’t fair to expect teachers to completely separate their spiritual function from their secular labors.

We need not and do not assume that teachers in parochial schools will be guilty of bad faith or any conscious design to evade the limitations imposed by the statute and the First Amendment. We simply recognize that a dedicated religious person, teaching in a school affiliated with his or her faith and operated to inculcate its tenets, will inevitably experience great difficulty in remaining religiously neutral.

Doctrines and faith are not inculcated or advanced by neutrals. With the best of intentions, such a teacher would find it hard to make a total separation between secular teaching and religious doctrine…

Finally, expecting the state to supervise or punish violations of this unattainable “total separation” created the exact sort of entanglement the First Amendment hoped to circumvent. It made the government into the theology police.

To ensure that no trespass occurs, the State has therefore carefully conditioned its aid with pervasive restrictions…

Unlike a book, a teacher cannot be inspected once so as to determine the extent and intent of his or her personal beliefs and subjective acceptance of the limitations imposed by the First Amendment. These prophylactic contacts will involve excessive and enduring entanglement between state and church.

In other words, the unacceptable entanglement between state and church starts with a well-intentioned effort to protect both from unconstitutional interaction. That said, one can’t help but wonder whether it was Justice Berger himself or some smirking law clerk who thought “prophylactic contacts” was a great way to express this. Then again, perhaps when it comes to phrasing we should allow written opinions a little play in the joints.

The Aftermath

So, bus fare and math books are OK. Government-led prayer or devotional readings are not. And, after Lemon, direct support to sectarian schools – under whatever formula – was out as well (at least for the next half-century). There would be other church-state cases in subsequent years, but those coming closest to the issues in Lemon involved questions of “school choice” and “vouchers.” Because the aid in question is primarily intended for parents and students, proponents argue these options are entirely constitutional – just like in Allen or Everson. Opponents insist that the intent and actual impact of such programs hurts public schools in favor of sectarian institutions, which seems like it must violate something in the “Lemon Test,” and is in any case has the state once again inching towards entanglement without the appropriate prophylactics.

In short, the “Lemon Test” brought some much-needed clarity to issues involving the separation of church and state. Shortly thereafter, people found a way to complicate it again.

Excerpts from Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), Majority Opinion by Chief Justice Warren Burger {Edited for Readability}

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), this Court upheld a state statute that reimbursed the parents of parochial school children for bus transportation expenses. There, Mr. Justice Black, writing for the majority, suggested that the decision carried to “the verge” of forbidden territory under the Religion Clauses. Candor compels acknowledgment, moreover, that we can only dimly perceive the lines of demarcation in this extraordinarily sensitive area of constitutional law.

The language of the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment is, at best, opaque, particularly when compared with other portions of the Amendment. Its authors did not simply prohibit the establishment of a state church or a state religion, an area history shows they regarded as very important and fraught with great dangers. Instead, they commanded that there should be “no law respecting an establishment of religion” … A given law might not establish a state religion, but nevertheless be one “respecting” that end in the sense of being a step that could lead to such establishment, and hence offend the First Amendment.

In the absence of precisely stated constitutional prohibitions, we must draw lines with reference to the three main evils against which the Establishment Clause was intended to afford protection: “sponsorship, financial support, and active involvement of the sovereign in religious activity” (Walz v. Tax Commission, 1970).

Every analysis in this area must begin with consideration of the cumulative criteria developed by the Court over many years… First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion (Board of Education v. Allen, 1968); finally, the statute must not foster “an excessive government entanglement with religion” (Walz).

Inquiry into the legislative purposes of the Pennsylvania and Rhode Island statutes affords no basis for a conclusion that the legislative intent was to advance religion. On the contrary, the statutes themselves clearly state that they are intended to enhance the quality of the secular education in all schools covered by the compulsory attendance laws. There is no reason to believe the legislatures meant anything else. A State always has a legitimate concern for maintaining minimum standards in all schools it allows to operate…

The two legislatures, however, have also recognized that church-related elementary and secondary schools have a significant religious mission, and that a substantial portion of their activities is religiously oriented. They have therefore sought to create statutory restrictions designed to guarantee the separation between secular and religious educational functions… We need not decide whether these legislative precautions restrict the principal or primary effect of the programs to the point where they do not offend the Religion Clauses, for we conclude that the cumulative impact of the entire relationship arising under the statutes in each State involves excessive entanglement between government and religion…

Our prior holdings do not call for total separation between church and state; total separation is not possible in an absolute sense. Some relationship between government and religious organizations is inevitable… Fire inspections, building and zoning regulations, and state requirements under compulsory school attendance laws are examples of necessary and permissible contacts. Indeed, under the statutory exemption before us in Walz, the State had a continuing burden to ascertain that the exempt property was, in fact, being used for religious worship. Judicial caveats against entanglement must recognize that the line of separation, far from being a “wall,” is a blurred, indistinct, and variable barrier depending on all the circumstances of a particular relationship…

The church schools involved in the {Rhode Island} program are located close to parish churches… The school buildings contain identifying religious symbols such as crosses on the exterior and crucifixes, and religious paintings and statues either in the classrooms or hallways. Although only approximately 30 minutes a day are devoted to direct religious instruction, there are religiously oriented extracurricular activities. Approximately two-thirds of the teachers in these schools are nuns of various religious orders. Their dedicated efforts provide an atmosphere in which religious instruction and religious vocations are natural and proper parts of life in such schools…

On the basis of these findings, the District Court concluded that the parochial schools constituted “an integral part of the religious mission of the Catholic Church.” The various characteristics of the schools make them “a powerful vehicle for transmitting the Catholic faith to the next generation.” This process of inculcating religious doctrine is, of course, enhanced by the impressionable age of the pupils, in primary schools particularly. In short, parochial schools involve substantial religious activity and purpose…

In Allen, the Court refused to make assumptions, on a meager record, about the religious content of the textbooks that the State would be asked to provide. We cannot, however, refuse here to recognize that teachers have a substantially different ideological character from books. In terms of potential for involving some aspect of faith or morals in secular subjects, a textbook’s content is ascertainable, but a teacher’s handling of a subject is not. We cannot ignore the danger that a teacher under religious control and discipline poses to the separation of the religious from the purely secular aspects of pre-college education. The conflict of functions inheres in the situation…

The teacher is employed by a religious organization, subject to the direction and discipline of religious authorities, and works in a system dedicated to rearing children in a particular faith. These controls are not lessened by the fact that most of the lay teachers are of the Catholic faith. Inevitably, some of a teacher’s responsibilities hover on the border between secular and religious orientation.

We need not and do not assume that teachers in parochial schools will be guilty of bad faith or any conscious design to evade the limitations imposed by the statute and the First Amendment. We simply recognize that a dedicated religious person, teaching in a school affiliated with his or her faith and operated to inculcate its tenets, will inevitably experience great difficulty in remaining religiously neutral. Doctrines and faith are not inculcated or advanced by neutrals. With the best of intentions, such a teacher would find it hard to make a total separation between secular teaching and religious doctrine…

A comprehensive, discriminating, and continuing state surveillance will inevitably be required to ensure that these restrictions are obeyed and the First Amendment otherwise respected. Unlike a book, a teacher cannot be inspected once so as to determine the extent and intent of his or her personal beliefs and subjective acceptance of the limitations imposed by the First Amendment. These prophylactic contacts will involve excessive and enduring entanglement between state and church…

Finally, nothing we have said can be construed to disparage the role of church-related elementary and secondary schools in our national life… The sole question is whether state aid to these schools can be squared with the dictates of the Religion Clauses… The Constitution decrees that religion must be a private matter for the individual, the family, and the institutions of private choice, and that, while some involvement and entanglement are inevitable, lines must be drawn.

*Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

*Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.