On November 17, 1980, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Stone v. Graham – a case involving the required posting of the Ten Commandments on the wall of every classroom in Kentucky.

On November 17, 1980, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Stone v. Graham – a case involving the required posting of the Ten Commandments on the wall of every classroom in Kentucky.

This was about a month after the release of “Another One Bites the Dust” (Queen), although “Lady” (Kenny Rogers) was at that moment sitting comfortably at the top of the charts. It was less than a month before John Lennon would be murdered and “Just Like Starting Over” would be released and soar to #1.

Reagan had just been elected, although he wouldn’t take office until January, 1981. The nation was approaching Day 400 of the Iranian Hostage Crisis. The “Miracle on Ice” had occurred earlier that year, back when only “amateurs” were allowed to compete in the Olympics. The Rubik’s Cube had just become a thing, Richard Pryor had recently lit himself on fire, and the nation seemed genuinely concerned with figuring out “Who Shot J.R.?”

None of which has anything to do with the case. Just trying to provide a little context, since for some of us 1980 seems like last month, while for others it might as well have been the year they began construction on the Great Wall of China.

So, this case…

The State of Kentucky required that a copy of the Ten Commandments be posted on the wall of every public school classroom. The Commandments were purchased via private contributions, so no state money was used, and teachers were not required to discuss, promote, or even draw attention to the Commandments so posted.

At the bottom of each copy was this explanation: “The secular application of the Ten Commandments is clearly seen in its adoption as the fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States.”

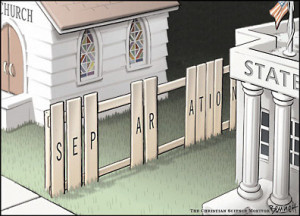

If you’ve been reading this series on the “Wall of Separation,” you know how this one is going to go – right?

The Court referenced the “Lemon Test” which emerged from Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) less than a decade before. This “test” has three parts, but the Court never got to the second base on this one, let alone third.

First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose…

That did it. Shut it down.

They didn’t buy at all the assertion that the Ten Commandments were being used in a primarily secular way or to secular purpose. Had the curriculum included additional examples of historical laws, or a study of the Old Testament as literature, history, or even as a world religion, it would have been fine. As it stood, however, the Commandments were without educational context. Instead, they demanded fealty to a certain God in a certain way following specific interpretations of what that God said and wanted.

Also known as “an establishment of religion.”

It didn’t matter who’d paid for them – the state was requiring and posting them. That’s not how “separation of church at state” works.

Stone vs. Graham (1980) is interesting for several reasons. Well, to me, at least…

It was decided per curium, meaning the majority opinion was issued as written by the Court as a whole rather than a specific Justice. A per curium decision is traditionally used in far more banal situations – explaining why the Court will or won’t hear a case, or when the result is considered obvious or non-controversial.

Given that this was a 5-4 split decision, that clearly wasn’t the case. So the anonymous majority opinion is weird. It’s also not entirely anonymous, since Justice Rehnquist wrote a dissent and three other Justices agreed with it. Let’s see, nine Justices, minus those four…

The Supremes also decided this one without hearing arguments from either side. I didn’t know this was a thing, but presumably they figured the lower courts had covered everything they needed to know in order to decide.

Finally, Stone was one of the first cases to rule against such a “passive display” of religion as nevertheless violating the Establishment Clause. It was from this reasoning the Court went on to take issue with some government-sponsored Christmas displays and other state-sanctioned religious ceremonies.

Let’s see if there’s anything fun in this per curium opinion, shall we?

Hmm… they referenced Abington v. Schempp (1963). We’ve covered that one, yes?

They then went straight to the “Lemon Test” – another familiar item to the #11FF.

They eventually referenced Engel v. Vitale (1962) as well. I swear, it’s like they read my blog even back then!

The Court notes that while some of the Commandments are “arguably secular matters, such as honoring one’s parents, killing or murder, adultery, stealing…” others are very specific to “the religious duties of believers: worshipping the Lord God alone, avoiding idolatry, not using the Lord’s name in vain, and observing the Sabbath Day.”

As in Abington, the Court wants to make sure their decision is not perceived as forbidding all discussion of religious topics:

This is not a case in which the Ten Commandments are integrated into the school curriculum, where the Bible may constitutionally be used in an appropriate study of history, civilization, ethics, comparative religion, or the like…

Posting of religious texts on the wall serves no such educational function. If the posted copies of the Ten Commandments are to have any effect at all, it will be to induce the schoolchildren to read, meditate upon, perhaps to venerate and obey, the Commandments. However desirable this might be as a matter of private devotion, it is not a permissible state objective under the Establishment Clause.

There’s a great moment in Justice Rehnquist’s dissent worth sharing here:

The Establishment Clause does not require that the public sector be insulated from all things which may have a religious significance or origin. This Court has recognized that “religion has been closely identified with our history and government”… and that “{t}he history of man is inseparable from the history of religion”…

Kentucky has decided to make students aware of this fact by demonstrating the secular impact of the Ten Commandments. The words of Justice Jackson, concurring in McCollum v. Board of Education (1948), merit quotation at length:

And yes, I’m about to move from quoting an opinion to quoting an opinion quoted within an opinion. Is it getting Inception up in here?

I think it remains to be demonstrated whether it is possible, even if desirable, to comply with such demands as plaintiff’s completely to isolate and cast out of secular education all that some people may reasonably regard as religious instruction.

Perhaps subjects such as mathematics, physics or chemistry are, or can be, completely secularized. But it would not seem practical to teach either practice or appreciation of the arts if we are to forbid exposure of youth to any religious influences. Music without sacred music, architecture minus the cathedral, or painting without the scriptural themes would be eccentric and incomplete, even from a secular point of view…

I should suppose it is a proper, if not an indispensable, part of preparation for a worldly life to know the roles that religion and religions have played in the tragic story of mankind. The fact is that, for good or for ill, nearly everything in our culture worth transmitting, everything which gives meaning to life, is saturated with religious influences, derived from paganism, Judaism, Christianity – both Catholic and Protestant – and other faiths accepted by a large part of the world’s peoples.

One can hardly respect the system of education that would leave the student wholly ignorant of the currents of religious thought that move the world society for a part in which he is being prepared.

That last part is significant – “the currents or religious thought that move the world society for a part in which he is being prepared.”

In other words, no student is truly prepared to go out into the world without a basic familiarity with the VARIOUS faiths and cultural norms of the world – not merely their own.

At some point we’ll have to look at how this decision impacted the ability of a state to post the Ten Commandments in other places – say, at that State Capitol or some such thing. Just, you know… hypothetically.

But not this time.

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Everson v. Board of Education (1947)

RELATED POST: Building a Wall of Separation (Faith & School)

RELATED POST: The Blaine Game

*Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

*Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.