So I’ve written and published a book of important Supreme Court cases:

I’ve considered blogging about the process itself in hopes it might help others considering something similar, but I’m pretty sure the way I approach most things is roundabout and unnecessarily convoluted and would probably make any reasonable person want run from the room screaming. I will say this, though – it’s an amazing feeling to finally have it done. It’s also overwhelming the number of things that go wrong in the process itself and the volume of errors and problems you discover the first time your baby finally goes live – all of which can be traced back to me one way or the other.

Don’t worry, though – everything in it is fixed and practically perfect now. You should absolutely buy a few dozen copies. They make great gifts, look good on any bookshelf (at home, school, or other workplace), and they’re just the right thickness to go under unbalanced tables or chairs or give a little boost to your computer when live conferencing so your chin doesn’t look chubby.

“Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases: Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About The Most Important Cases In Supreme Court History (I know – catchy, isn’t it?) was a project which began largely for my own reference and classroom use. Some of the material I posted here on Blue Cereal as early drafts. I wasn’t always focused on “landmark” cases – much like with anything in history, for every thread you pull, every question you pose, every rabbit you chase, there are something like a four-hundred and eleven new threads, questions, and rabbits begging to be pulled, posed, and chased – and not always in that order. It doesn’t require you to be particularly knowledgeable or profound; it’s a simple function of focusing on, well… anything, for any real length of time.

As I tell my students, when history is “boring,” the problem isn’t the history. It’s them.

At some point I began wondering if my efforts might prove useful to other educators in their various circumstances. I’m under no illusions about my own abilities, but there’s so much out there and so little time to really dig through it; you never really know what others might find helpful. I pulled together fifteen or so cases, excerpts from the Court’s written opinions, and some questions I’d written as “scaffolding” for my less-enthusiastic classes. I added a few more for sake of completion, along with some simple graphic organizers to manage major periods with multiple related cases.

I initially posted the final product to Teachers Pay Teachers along with a dozen other items. I have mixed feelings about TPT – I’m not against it, necessarily, but I’ve always preferred to simply share whatever I have that others might find useful. Then again, none of us seem to be against getting paid for leading workshops or writing teacher books promising this year’s magical cure to all the things, so I’m not sure why there’s so much faux outrage at those willing to offer up their own labor and creations for a few bucks so they can buy grandma that penicillin.

I sold a few items, but not enough to justify how I was feeling about it. My principles may be for sale, but I’d like to think the price is a little higher than what I was making.

Plus, I gradually realized several things which should have already been obvious. First, not every class needs the same sorts of questions or guidelines, even if they are studying some of the same cases. Second, if my goal was to self-publish the final product (which over time seemed more and more likely), I was limiting its usefulness by formatting it as a “workbook” of some sort. I mean, I read all sorts of nerdy things from other subjects or fields, but I’m not sure I’d actually pay for something if I thought half of the cost was for “homework” I wasn’t going to do. Finally, I’m in a one-to-one school. I tend to assume students can easily look up any relevant information not explicitly covered in the content. That means my questions aren’t always limited to stuff from the materials I’ve provided; they regularly include relevant background info one can easily Yahoo.

In short, my constant second-guessing became a bit silly. I deleted my TPT account and decided to write something which might appeal to students, teachers, or actual people in roughly equal proportions.

I combed several sets of state standards for American History and U.S. Government, plodded through the official Course Descriptions for APUSH and AP-GOV to make sure I included every case referenced in either (whether I’d have chosen those personally or not), and revised my summaries to make them as useful as possible for both students and teachers while remaining as accessible as possible to people who simply wanted to understand a little more about what the hell was going on with this or that issue in the news today.

I’m not saying the final product is perfect, but there’s a reason it took a year longer than I’d planned. (Plus, the final product really is perfect – I was just trying to be humble.)

Because this post is serving the dual purpose of sharing supplemental goodies while working in a subtle promo for you to open a new tab and buy the book, I’ll even share the final description from the (quite stylish) back cover:

Whether you’re a student trying to fake your way through an American History or Government class, a loyal American citizen seeking constitutional context for current events, or simply trying to look smart on a budget, “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases covers all the stuff you don’t really want to know (but for some reason have to) about 44 of the most important cases in our collective history. From midnight judges to gay marriage, internment camps to presidential shenanigans, you’ll find yourself looking more thoughtful and insightful just by leaving a few copies lying around. And if you actually read it, well… your credibility and self-confidence will soar and you’ll start decisively winning all of those arguments on social media. (Just tell them you have the book!)

Each featured case comes with historical context, the “three big things” you should remember, and an explanation of the decision and why we’re still talking about it today. Excerpts from the Court’s majority opinions are included, along with interesting bits from important concurring or dissenting opinions (so you can take in the Court’s reasoning in its own words). Additional “worth-a-look” cases are presented in compact form with brief highlights from the Court’s decision and a quick summary of the case and why it mattered. “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases is readable and fresh and covers everything likely to be on the test.

Take that last bit as literally or metaphorically as you wish.

Once everything was finally finished and published, I started thinking that it might still be useful to a few teachers to have those questions and graphic organizers and whatnot – especially if they weren’t something they were expected to purchase. I added a few more to go with the expanded format of the book, and here we are.

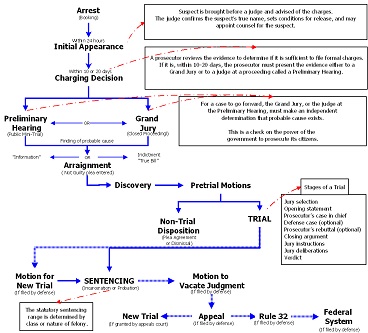

I’ve attached the same materials in two different versions. The “All” file, not surprisingly, has everything in a single PDF document. The “Questions” file has just the questions over case summaries and written opinions, and the remaining attachments are the various graphic organizers from the “All” file but in higher quality PDFs of their own. There’s also a summary of how the courts work which I didn’t write but have used in class from time to time.

Do with any or all of it as you see fit – or don’t. I genuinely hope some of it’s useful. If so, I’d love to know. If you create better stuff and you’re willing to share, send it along and I’ll post it.

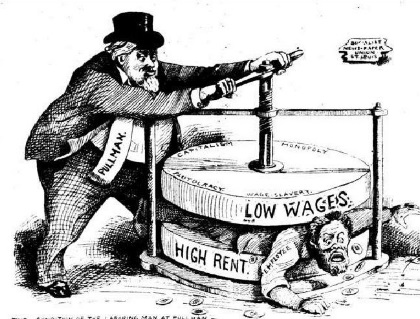

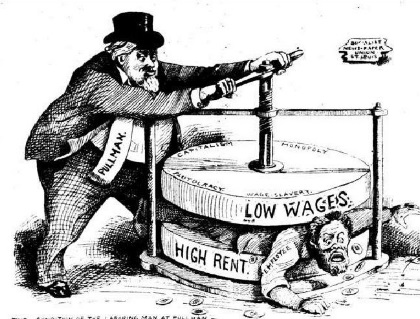

“School choice” wouldn’t emerge onto the national scene until after Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the various forays into moral corruption and social decay wouldn’t become staples of the nation’s highest court until a decade after that. The rest of the Lochner Era was largely about how freedom meant letting corporations do whatever they wanted to workers because those being exploited had just as much theoretical control over the outcome as their gilded overlords did. (They didn’t put it in those exact terms.) Between 1897 – 1937, the Supreme Court struck down nearly 200 different statues, most as violations of “freedom of contract” or other violation of “economic substantive due process.”

“School choice” wouldn’t emerge onto the national scene until after Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the various forays into moral corruption and social decay wouldn’t become staples of the nation’s highest court until a decade after that. The rest of the Lochner Era was largely about how freedom meant letting corporations do whatever they wanted to workers because those being exploited had just as much theoretical control over the outcome as their gilded overlords did. (They didn’t put it in those exact terms.) Between 1897 – 1937, the Supreme Court struck down nearly 200 different statues, most as violations of “freedom of contract” or other violation of “economic substantive due process.” Adair v. United States (1908) – Congress passed legislation in 1898 prohibiting “yellow dog contracts” in which workers agreed to forego union membership in order to obtain employment. When an interstate railroad company nevertheless fired an employee for joining a labor union, they argued that the Fifth Amendment protected them from being deprived of their liberty or property without due process (no doubt meaning the “substantive” variety). The Supreme Court agreed. While Congress had the right to regulate interstate commerce, that didn’t give them the right to interfere in the “liberty of contract” between employers and employees.

Adair v. United States (1908) – Congress passed legislation in 1898 prohibiting “yellow dog contracts” in which workers agreed to forego union membership in order to obtain employment. When an interstate railroad company nevertheless fired an employee for joining a labor union, they argued that the Fifth Amendment protected them from being deprived of their liberty or property without due process (no doubt meaning the “substantive” variety). The Supreme Court agreed. While Congress had the right to regulate interstate commerce, that didn’t give them the right to interfere in the “liberty of contract” between employers and employees. Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923) – The District of Columbia passed a minimum wage law for women and minors, complete with provisions for investigation and enforcement. The Children’s Hospital of D.C. protested that this was a violation of their “freedom of contract” as clearly established in Lochner v. New York (1905). The Supreme Court agreed and overturned the minimum wage legislation based on the same principles articulated in Lochner, adding that the law was “arbitrary” in that it imposed a uniform minimum wage regardless of women’s individual skills, occupations, wants, or needs. Besides, the Court added, with the passage of the 19th Amendment only a few years before, the idea that women required special protection was quickly becoming antiquated.

Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923) – The District of Columbia passed a minimum wage law for women and minors, complete with provisions for investigation and enforcement. The Children’s Hospital of D.C. protested that this was a violation of their “freedom of contract” as clearly established in Lochner v. New York (1905). The Supreme Court agreed and overturned the minimum wage legislation based on the same principles articulated in Lochner, adding that the law was “arbitrary” in that it imposed a uniform minimum wage regardless of women’s individual skills, occupations, wants, or needs. Besides, the Court added, with the passage of the 19th Amendment only a few years before, the idea that women required special protection was quickly becoming antiquated. When the case reached the Supreme Court, however, they found for Parrish and the State of Washington. The minimum wage was fine. Adkins was officially overturned. Just like that, the Lochner Era was over.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, however, they found for Parrish and the State of Washington. The minimum wage was fine. Adkins was officially overturned. Just like that, the Lochner Era was over.  In an instant, the “economic substantive due process” went from being head cheerleader to the weird girl no one would invite to parties. It fell out of favor, seemingly inexplicably, and has been generally villified ever since. Lochner v. New York (1905) is now regularly lumped together on “worst ever” lists with cases like Scott v. Sandford (1857), Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), and Citizens United v. FEC (2010).

In an instant, the “economic substantive due process” went from being head cheerleader to the weird girl no one would invite to parties. It fell out of favor, seemingly inexplicably, and has been generally villified ever since. Lochner v. New York (1905) is now regularly lumped together on “worst ever” lists with cases like Scott v. Sandford (1857), Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), and Citizens United v. FEC (2010).

Crowded, dirty, dangerous cities and the evolving power of media to reveal “how the other half lives” brought about what would be remembered as the “Progressive Era.” Reformers began staking out victories, primarily at the municipal level – although by 1920 they could celebrate four new constitutional amendments as well. Both churches and charities were inspired by the idea that individuals, with a little help and “encouragement,” could improve. Individuals make up families, families make up societies… the world could become a better place, starting with the education of one child, the health of one mother, the reform of one man.

Crowded, dirty, dangerous cities and the evolving power of media to reveal “how the other half lives” brought about what would be remembered as the “Progressive Era.” Reformers began staking out victories, primarily at the municipal level – although by 1920 they could celebrate four new constitutional amendments as well. Both churches and charities were inspired by the idea that individuals, with a little help and “encouragement,” could improve. Individuals make up families, families make up societies… the world could become a better place, starting with the education of one child, the health of one mother, the reform of one man.

The most common understanding of this principle involves “procedural due process.” Anyone accused of a serious crime is guaranteed a fair trial before a jury of their peers. They have a right to an attorney and there are limits as to how the State may go about making the case against them. “Procedural due process” refers to the steps which must be taken and the hurdles which must be cleared before any level of government can take or limit your life, liberty, or stuff – whether the issue is property taxes, prison time, or capital punishment. The concept isn’t limited to criminal law; “due process” is also the steps your public school has to go through before suspending or expelling little Marco for his various violations, and why his guardians or other advocates have the right to challenge the system along the way.

The most common understanding of this principle involves “procedural due process.” Anyone accused of a serious crime is guaranteed a fair trial before a jury of their peers. They have a right to an attorney and there are limits as to how the State may go about making the case against them. “Procedural due process” refers to the steps which must be taken and the hurdles which must be cleared before any level of government can take or limit your life, liberty, or stuff – whether the issue is property taxes, prison time, or capital punishment. The concept isn’t limited to criminal law; “due process” is also the steps your public school has to go through before suspending or expelling little Marco for his various violations, and why his guardians or other advocates have the right to challenge the system along the way. What “substantive due process” protects, then, are what we sometimes refer to as “unenumerated rights” – protections implied by the written words of the Constitution and its Amendments, perhaps even inherent in them, but not spelled out as such. In the Lochner Era, this primarily referred to “economic substantive due process” – ideas like “freedom of contract” between companies and workers. It was during this same era, however, that two cases were decided largely on the basis of “substantive due process” which had nothing to do with workers rights or minimum wages. Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) involved the right of parents to determine the specifics of their child’s education and of educators to offer wildly controversial courses like foreign languages. Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) allowed parents to choose private schooling, religious or otherwise.

What “substantive due process” protects, then, are what we sometimes refer to as “unenumerated rights” – protections implied by the written words of the Constitution and its Amendments, perhaps even inherent in them, but not spelled out as such. In the Lochner Era, this primarily referred to “economic substantive due process” – ideas like “freedom of contract” between companies and workers. It was during this same era, however, that two cases were decided largely on the basis of “substantive due process” which had nothing to do with workers rights or minimum wages. Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) involved the right of parents to determine the specifics of their child’s education and of educators to offer wildly controversial courses like foreign languages. Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) allowed parents to choose private schooling, religious or otherwise. The dilemma of any effort to compile “must know” Supreme Court cases is deciding where to draw the line. If you narrow it to a list of 12, there are at least 3 or 4 others that really MUST be added in the name of consistency. If you expand the list to, say… 24, you’re sacrificing another half-dozen that should simply NOT be neglected if you’re to retain ANY credibility.

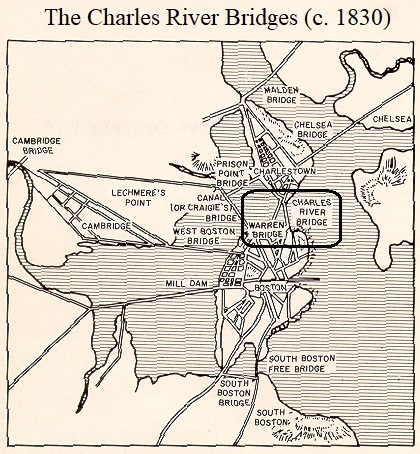

The dilemma of any effort to compile “must know” Supreme Court cases is deciding where to draw the line. If you narrow it to a list of 12, there are at least 3 or 4 others that really MUST be added in the name of consistency. If you expand the list to, say… 24, you’re sacrificing another half-dozen that should simply NOT be neglected if you’re to retain ANY credibility. In 1828, the state legislature granted a new charter to the Warren River Bridge Company (WRBC), who built a second bridge not all that far from the first. This bridge, however, was to be toll-free once initial costs were recovered and a reasonable profit earned for the company. Not surprisingly, people liked this bridge much better. The Charles River Bridge Company sued in state court, claiming the new charter violated their property rights and represented a broken contract by the State of Massachusetts. Not only was this very naughty, they argued, but it violated Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution, which says (among other things) that “no state shall… pass any… law impairing the obligation of contracts…”

In 1828, the state legislature granted a new charter to the Warren River Bridge Company (WRBC), who built a second bridge not all that far from the first. This bridge, however, was to be toll-free once initial costs were recovered and a reasonable profit earned for the company. Not surprisingly, people liked this bridge much better. The Charles River Bridge Company sued in state court, claiming the new charter violated their property rights and represented a broken contract by the State of Massachusetts. Not only was this very naughty, they argued, but it violated Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution, which says (among other things) that “no state shall… pass any… law impairing the obligation of contracts…” The Supreme Court rejected this line of reasoning and validated the “Granger Laws” as entirely appropriate and constitutional. Since before the founding of the United States, Chief Justice Waite explained, the foundational purpose of enlightened government is to support and regulate the social contract – each citizen giving up a small bit of autonomy for the larger good. In the end, this benefits everyone, including those making these minor sacrifices.

The Supreme Court rejected this line of reasoning and validated the “Granger Laws” as entirely appropriate and constitutional. Since before the founding of the United States, Chief Justice Waite explained, the foundational purpose of enlightened government is to support and regulate the social contract – each citizen giving up a small bit of autonomy for the larger good. In the end, this benefits everyone, including those making these minor sacrifices.