NOTE: I’m revising and reorganizing much of the content from “Well, OK Then” as part of an overall effort to ‘clean up’ this site. This post is one of those newer, better versions of something previously shared.

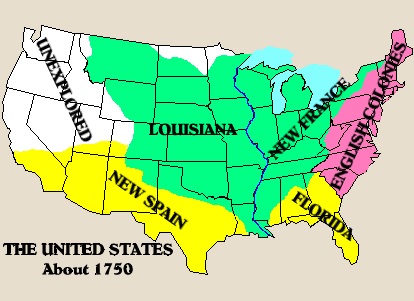

The first European nation to lay claim to what is now Oklahoma was Spain, via wanderings sent forth from New Spain – what today is Mexico.

The first European nation to lay claim to what is now Oklahoma was Spain, via wanderings sent forth from New Spain – what today is Mexico.

Other than periodic expeditions hoping perhaps there was more to the Great Plains than met the eye, the Spanish weren’t particularly enamored with the northeastern-most reaches of their claims in the New World. They weren’t looking to colonize or expand on the same scale as their Anglo cousins, and the whole area was just… flat. And hot. And completely bereft of gold, more gold, or all the gold.

The neglect became permanent after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 by the English, with substantial assistance from a suddenly very-Protestant God. Spain was already struggling to maintain its role as a major player back home in Europe, and no longer had the energy for shenanigans in the Western Hemisphere – not without a greater payoff.

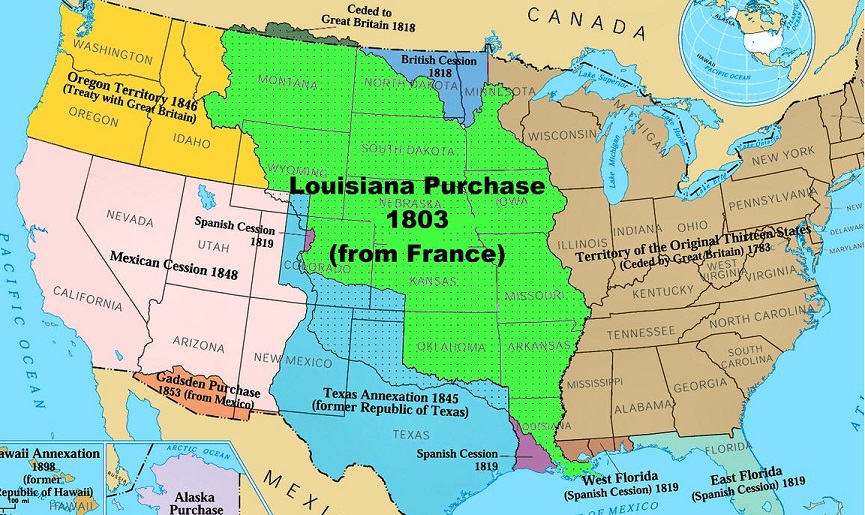

Little surprise, then, that the French met with little resistance when they claimed a big ol’ chunk of the New World as “Louisiana Territory” in 1682. The original boundaries looked a little different than they would 121 years later when Jefferson made his famous “Purchase” of the same name, but Oklahoma was included in both versions.

The French did exactly nothing, near as we can tell, in this part of the Territory while under their purview. Not that we needed them here, getting their… Frenchness all over us. But still – it would have been nice to be wanted, you know?

The area changed hands again at the end of the French and Indian War – the same one most of you remember from American History class. You may recall that it wasn’t the French vs. the Indians; they were allies against the British colonies along the eastern coast of North America. Like most things, it was complicated – part of a larger “Seven Years War” going on in Europe, and mixing itself into pre-existing issues between the colonies and the locals, etc.

It was at the conclusion of this war in 1763 that the British first got serious about raising taxes on the American colonists to help offset some of the costs of their “protection.” This sparked a whole other series of events more familiar to the average student and leading to seriously overpriced fireworks every summer.

In any case, the Treaty of Paris (1763) transferred proud ownership of all this flat, red dirt to the British, despite a secret agreement handing it over to Spain only a year before. It says something about the status of pre-settlement Oklahoma that Spain didn’t even fuss over this double-dealing; their primary concern involved other territories included in that exchange.

In any case, the Treaty of Paris (1763) transferred proud ownership of all this flat, red dirt to the British, despite a secret agreement handing it over to Spain only a year before. It says something about the status of pre-settlement Oklahoma that Spain didn’t even fuss over this double-dealing; their primary concern involved other territories included in that exchange.

That explains, however, how land arguably belonging to the British could be returned to France by Spain in the year 1800. These were the days of Napoleonic hegemony – the proverbial “little general” who wanted to take over all of the known world.

EXCEPT OKLAHOMA BECAUSE WHY BOTHER AND HEY T.J., WANNA BARGAIN ON SOME BIG, FLAT, USELESS LAND?

Um… hello?! Potential state here! Home of natural resources and flora and fauna and stuff? Wind, sweeping down the plains? Hawks with questionable work ethics circling above? I get that we’re not the prettiest state in the room, but we’re at least… OK, right?

*sigh*

And people wonder why to this day we’re one giant inferiority complex, with a side of paranoid delusion. Texas proudly waves its ‘six flags’ representing various stages of its history. We had three prior to statehood, playing ‘hot potato’ with us like the homely friend of the popular girls they were really looking to – um… “homestead.”

But finally, a nation that needed us! That could appreciate us! Say what you like about the early U.S., they were some exploring and expanding fools! President Jefferson sent out Lewis and Clark and Co., who began mapping the entire area of –

Hey! Where are you going? Meriwether! Bill! Down here, big fellas! It’s me, Okla –

*sigh*

Sunnuvabitch. The Dakotas. They’re all hot’n’bothered for Nebraska and the Dakotas. Seriously?

Fine. We’ll waive our *mumble* wheat for someone *murmur* can appreciate *grouse* land we belong to is grandma’s crusty *obsenitiesandbitterness*.

Fine. We’ll waive our *mumble* wheat for someone *murmur* can appreciate *grouse* land we belong to is grandma’s crusty *obsenitiesandbitterness*.

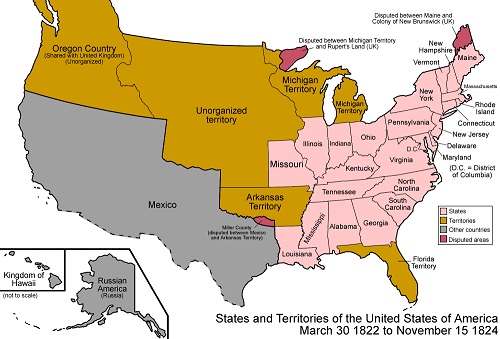

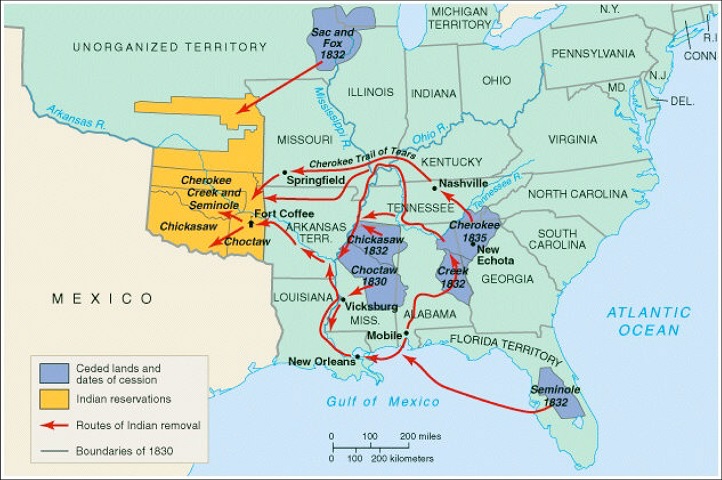

There was thus very little to discuss between our inconspicuous transition into United States Territorial-ness in 1803 and the involuntary arrival of the Five Civilized Tribes via “Indian Removal” in the 1830s.

Meanwhile, white America was expanding much more quickly than expected. Immigrants were packing the shores, and those already here were spawning like blind prawn. While encounters with Amerindian natives had produced mixed results since the time Columbus first mislabeled them, five tribes in the southeastern part of the country had adapted far better than most, and conflicts had been relatively minimal.

The Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole, while distinct peoples in and of themselves, became collectively known as the “Five Civilized Tribes” (5CT). Keep in mind, of course, that this was not a self-selected title – it was bestowed by white Southerners in the area. This use of “civilized” wasn’t drawn from someone’s textbook definition or discerned anthropologically; it meant that these Indians were a lot more like the white folks around them than them other Indians, who were generally considered savage, wild, and dangerous. Decadent, actually.

Boo, savage Indians!

The 5CT, in contrast, were largely agricultural. They were far less nomadic, more highly educated, and far less likely to practice hit’n’run raids on white neighbors. Many converted to or at least adapted elements of Christianity, even wearing uncomfortable shoes and learning English in order to facilitate good relations.

If the primary cause of conflict with Natives was cultural, as is often asserted, then the 5CT should have had little trouble with the wave of white settlement surrounding them. If it were purely an issue of gold or other mineral wealth, as our textbooks like to emphasize, the problem would have been substantially more localized.

But the U.S. found it necessary to violate a number of its own fundamental values and laws in order to kick FIVE distinct nations out of an area roughly the size of THREE entire states. They did so at enormous cost to themselves and unforgivable loss of life to those removed. This was driven by something bigger than gold, something fundamental to an expanding nation.

But the U.S. found it necessary to violate a number of its own fundamental values and laws in order to kick FIVE distinct nations out of an area roughly the size of THREE entire states. They did so at enormous cost to themselves and unforgivable loss of life to those removed. This was driven by something bigger than gold, something fundamental to an expanding nation.

White homesteaders wanted land. They needed land. They deserved land.

Not that they were likely to come right out and put it that way. From President Andrew Jackson’s First Annual Message to Congress, December 8th, 1829:

The consequences of a speedy removal will be important to the United States, to individual States, and to the Indians themselves. The pecuniary advantages which it promises to the Government are the least of its recommendations…

“Pecuniary”? He’s been reading Jefferson’s letters again. Not bad for an uneducated orphan kid, actually.

“Pecuniary” means financial, or profitable. Perhaps fiscal growth was the “least” of many reasons to move the Indians, but he sure didn’t waste any time mentioning it.

Like, first.

It will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters. By opening the whole territory between Tennessee on the north and Louisiana on the south to the settlement of the whites it will incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier and render the adjacent States strong enough to repel future invasions without remote aid…

See? Not all of our motivation is selfish and monetary. They’ll also make a nice buffer between us and the Apache. Why should we be carved open and burned alive if we can throw a few Chickasaw in the way instead?

It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.

What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion? …

There we go – the “besides, it’s good for them” defense. We used a variation of this to justify slavery, you may recall – saving all those crazy Africans from their ooga-booga religions and cannibalism and such, freeing them up to play banjos around the fire and partake of the finest Christian civilization.

There we go – the “besides, it’s good for them” defense. We used a variation of this to justify slavery, you may recall – saving all those crazy Africans from their ooga-booga religions and cannibalism and such, freeing them up to play banjos around the fire and partake of the finest Christian civilization.

It’s quite a mix of values, though, isn’t it? Removal will leave them alone to do their own thing, but it will also force them to become more like us – which is the opposite of being left alone and doing their own thing. Besides, Jackson explains, what good is a bunch of trees and land when we could pack in cities and industry and corporate-style farming?

Maybe he hadn’t been reading Jefferson after all.

The tribes which occupied the countries now constituting the Eastern States were annihilated or have melted away to make room for the whites. The waves of population and civilization are rolling to the westward, and we now propose to acquire the countries occupied by the red men of the South and West by a fair exchange, and, at the expense of the United States, to send them to land where their existence may be prolonged and perhaps made perpetual.

The term ‘Manifest Destiny’ hadn’t been coined yet, but the ideology permeates Jackson’s language. There are no individuals making choices, or cultures colliding – merely inevitable progress “rolling to the westward.”

Doubtless it will be painful to leave the graves of their fathers; but what do they more than our ancestors did or than our children are now doing? … {White settlers} remove hundreds and almost thousands of miles at their own expense, purchase the lands they occupy, and support themselves at their new homes from the moment of their arrival.

Can it be cruel in this Government when, by events which it cannot control, the Indian is made discontented in his ancient home to purchase his lands, to give him a new and extensive territory, to pay the expense of his removal, and support him a year in his new abode? How many thousands of our own people would gladly embrace the opportunity of removing to the West on such conditions! If the offers made to the Indians were extended to them, they would be hailed with gratitude and joy.

Jackson may be overdoing it a bit, even by the standards of the day. His primary purpose was most likely not to convert anyone adamantly opposed, but to assuage any guilt on the part of those already looking for an excuse. That’s why we talk about “audience” and “reason” when we do document analysis, kids – dead white guys can be sneaky.

Jackson may be overdoing it a bit, even by the standards of the day. His primary purpose was most likely not to convert anyone adamantly opposed, but to assuage any guilt on the part of those already looking for an excuse. That’s why we talk about “audience” and “reason” when we do document analysis, kids – dead white guys can be sneaky.

Whatever else Jackson was, he was a genuine champion of the “common man.” As a creature of his times, that rarely included the 5CT or anyone else with meaningful pigmentation – it meant white homesteaders.

Like the generation of Founders on whose shoulders he consciously stood, he recognized the connection between land and opportunity, land and character, land and democracy.

He was generally plainspoken, but that didn’t mean he had no understanding of human nature. He knew that sometimes lofty goals and hard decisions required… framing. He was no diplomat, but he was certainly willing to play the demagogue here and there if he believed his cause was deserving.

And there was no higher cause than this American nation. These people. This potential. He may have hated Indians, or he may have not. It didn’t matter. America had a destiny, and that destiny needed more land.

That chunk of Louisiana Territory that kept getting tossed around and ignored is about to become useful.