“Some things can be done as well as others.”

It’s not much of a catch phrase two hundred years later, but at the time, this line of Sam Patch’s was golden. It probably helped that he’d say it right before jumping off a waterfall. That would add a little drama, I’d think.

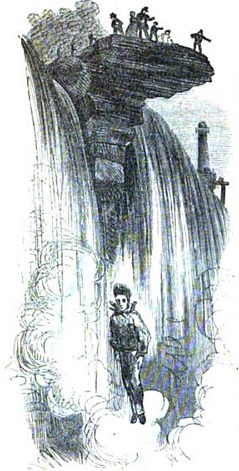

He’d stand near the crest – or, years later, on platforms or ladders built high above even that – and jump. Body position and breathing were critical from such heights. Knowing where you could and couldn’t safely enter the water at such speeds was pretty important, too. It also helped if you could swim.

Patch was fond of staying underwater after a leap for longer than seemed possible, creating tension and sparking nervous chatter among the crowd. On at least one less-public occasion he swam underwater to a sheltered cave area in order to hide out and panic his friends.

The problem with this is that if you’ve actually died this time, everyone thinks you’re just screwing with them. They figure you’re with Elvis somewhere, laughing at their gullibility.

Sam Patch grew up in early 19th century America, a transitional era during which Jefferson’s agricultural ideal was giving way to a more modern, urban, industrial society, albeit inconsistently, in scattered areas throughout the north. Patch grew up in a mill town, located along the Blackstone River near Providence, Rhode Island. Nature was harnessed and partially consumed, but still managed to assert itself beautifully and violently through displays like Pawtucket Falls.

However stunning the surroundings, these were necessarily utilitarian times. You didn’t come to Pawtucket if things in your life had gone according to plan; the remnants who found work in the mills were either without a male head of house, or stuck with one of little use. You came because you needed work, and Pawtucket was happy to oblige.

However stunning the surroundings, these were necessarily utilitarian times. You didn’t come to Pawtucket if things in your life had gone according to plan; the remnants who found work in the mills were either without a male head of house, or stuck with one of little use. You came because you needed work, and Pawtucket was happy to oblige.

These were days when owning land – even a little bit of land – was key to everything else: economic opportunity, social status, political participation. Almost as crucial were one’s extended family – social connections as well as surname. Neither were guarantees of anything, but both were essential to real opportunity in the realities of the times.

Patch had neither. He was, depending on your point of view, either a dirty, uneducated, ne’er-do-well, or the ideal candidate for a great American success story. Paging Horatio Alger… please meet your party at the waterfall…

You know all those nostalgic looks back to less safety-fied and sanitized times, when kids could play outside and get dirty or hurt and the species survived just fine? Patch’s adolescence was the epitome of this. Boys would jump from the main bridge above the river into ‘the pot’, a drop of about 50 feet into an opening carved by centuries of erosion. When that ceased to be terrifying, they’d jump from a nearby building instead, making a leap of around 80 feet straight down with a rather narrow margin of error.

A mistake of a few horizontal feet meant serious injury. If you were fortunate, you’d die suddenly and violently; if not, you’d experience untold broken bones and damn near drown before being hauled to shore and carried back to town to linger a day or two before an intensely painful death. With an audience.

So why do such a thing? Because they were boys, full of testosterone and competition and the rough sort of democracy available to the un-landed, the un-connected. Of course you could get hurt – that was the whole point. But if you had nerve, and skill, and didn’t…

There’s something insanely equitable and meritocratic about such behavior. Too innocent to be Social Darwinism, it nevertheless recognizes that there’s no ‘winning’ without a very real chance of ‘losing’. Without risk, there can be no glory – individually or nationally. Sam Patch and his ilk were in their own rough ways an idyllic, Tom Sawyer-ish, rough-edged version of the American dream – or at least its opening chapters.

Which isn’t the same as being part of the American reality, by the way. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Sam’s first public jump came in defiance of a man named Timothy Crane. Crane was probably not a bad man (in the dinner theater sense of the word), but he did reek of calculated sophistication, and that was bad enough. He’d purchased, ‘improved’, and privatized a public park-ish area near the mills, after which he began charging a small fee to enter.

Besides offsetting his costs, the fee was designed to screen out ne’er-do-wells. The park was designed for the ‘right’ kind of people, who were far more likely to both appreciate and take care of the area. Free admission, he feared, would allow the dregs and drunkards to spoil the space. Their inability to pay was indicative of far more than income level – it was a tag of behavior and education.

Besides offsetting his costs, the fee was designed to screen out ne’er-do-wells. The park was designed for the ‘right’ kind of people, who were far more likely to both appreciate and take care of the area. Free admission, he feared, would allow the dregs and drunkards to spoil the space. Their inability to pay was indicative of far more than income level – it was a tag of behavior and education.

You don’t really think those high dollar condos near the mall are that much nicer than the mid-range apartments ten minutes away, do you? Sure, you’re closer to the trendy restaurants – but mostly you’re paying too much for a condo in order to be surrounded by other people who can afford to pay too much for a condo.

It’s the same reason ‘golf’ somehow grew to be thought of as a real sport – the need to justify some basic elitism. Come on, you really thought it was THAT expensive to mow some grass and let people knock a tiny ball into a few holes in the ground? Please.

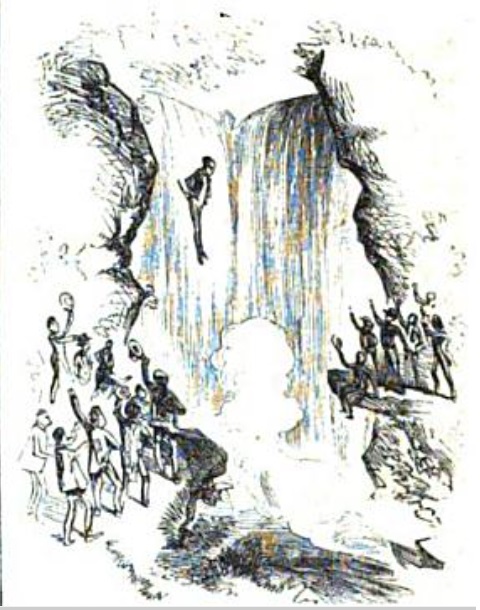

Crane’s crowing accomplishment was to be a rather ornate bridge which he had built and promised to have maneuvered across the chasm in front of Pawtucket Falls on September 30, 1827, for all to see. You have to keep in mind this is pre-Netflix, pre-Xbox, and even pre-television. Any potential entertainment was a big freaking deal, and this was no exception.

Schools and factories closed, and everyone came out to watch this engineering marvel finalize the glories of man-shaped nature, of improving and standardizing the bucolic. There are few things more American than making nature your bi-atch.

The mechanics of the process took much of the afternoon. At one point there was a small slip and one of the rolling logs being used to help guide and ‘roll’ the bridge across fell into the waters far below. The engineers recovered, but in the short time it took for them to readjust their contraptions, Sam Patch appeared on a rock at the edge of the cliff by the waterfall. He told the few people near him that Mr. Crane had done a great thing, and that he – Patch – meant to do another.

And he jumped.

Nothing in this prevented Crane from finishing his bridge, but for the crowd gathered that day the defiant message was clear. Patch, in channeling this brand of skill and moxy into such a primal act, was providing a sort of artistic and social contrast to the contrived high class aspirations of men like Crane. He was striking a blow for the common man.

Patch built on this theme several times in subsequent years, and eventually became something of a celebrity. Unfortunately, once you’re a celebrity – even in the 19th century equivalent of having a reality show – you’re not the common man anymore. The glories of having come from a dysfunctional family with no resources are all very well – but you’ve still come from a dysfunctional family with no resources. In other words, add a little notoriety, the stresses of minor success, and the chances you’ll become a complete wreck are pretty high.

In a few short years, Patch had a reputation as a drunk – usually the fun kind, but sometimes just the drunk kind. He somehow found himself bestowed with a pet bear, who he began taking with him and apparently lived with as a pet of sorts. And yes – the bear jumped off the same cliffs, bridges, and falls as Patch.

Well, if by ‘jumped’ you mean ‘was pushed or thrown’. Yeah, I know – but they were different times. And the bear seemed to be fine, so… go figure.

How many of YOUR friends can throw a bear off a cliff repeatedly and it’s still their friend?

On November 13, 1829, Sam made his last jump. Something went horribly wrong. It may have been the drinking or a related difficulty, but descriptions from those witnessing the event suggest he died in mid-air from something internal. His body positioning gave way and he fell limply for at least half of the 125 feet he spent in the air, striking the water with an impact which would have been fatal had he still been alive.

On November 13, 1829, Sam made his last jump. Something went horribly wrong. It may have been the drinking or a related difficulty, but descriptions from those witnessing the event suggest he died in mid-air from something internal. His body positioning gave way and he fell limply for at least half of the 125 feet he spent in the air, striking the water with an impact which would have been fatal had he still been alive.

Less than a year before, Andrew Jackson had been elected President of the United States. I’m going to argue the two events are related.

RELATED POST: Sam Patch (Part Two)

RELATED POST: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part One – This Land

RELATED POST: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part Two – Chosen People

If you’re from Oklahoma, or if you follow college football, or if you’ve ever been to OU, or if you have a pulse, you’ve probably more than once been subjected to the Hyper-Sousa-ish throb of the University of Oklahoma’s “Boomer Sooner.” If you’re truly dyed deep in just the right shade of maroon, you may even know the words:

If you’re from Oklahoma, or if you follow college football, or if you’ve ever been to OU, or if you have a pulse, you’ve probably more than once been subjected to the Hyper-Sousa-ish throb of the University of Oklahoma’s “Boomer Sooner.” If you’re truly dyed deep in just the right shade of maroon, you may even know the words: Those aren’t ALL of the words, of course – that would be silly. The second verse takes the theme to new depths:

Those aren’t ALL of the words, of course – that would be silly. The second verse takes the theme to new depths:

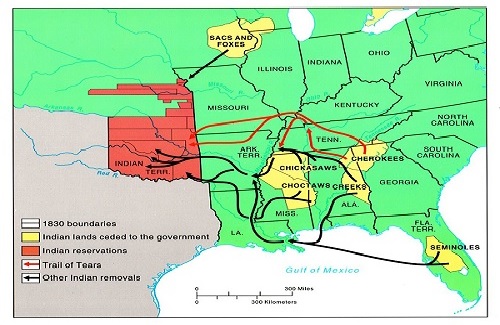

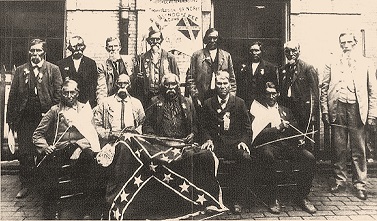

Only staying out of the conflict wasn’t as easy as they’d hoped. When pushed, many sympathized with the South, especially after Confederates promised them a better deal should they prevail. Some remained ‘loyal’ to the North, and a few went to great lengths to resist involvement altogether. Eventually, however, a majority of the 5CT were Confederates, including the colorful Stand Watie – the last Confederate General to officially surrender at the end of the war.

Only staying out of the conflict wasn’t as easy as they’d hoped. When pushed, many sympathized with the South, especially after Confederates promised them a better deal should they prevail. Some remained ‘loyal’ to the North, and a few went to great lengths to resist involvement altogether. Eventually, however, a majority of the 5CT were Confederates, including the colorful Stand Watie – the last Confederate General to officially surrender at the end of the war. That made room for the U.S. to begin packing in other tribes, this time mostly from the Great Plains. The Cheyenne, Arapaho, Wichita, Kickapoo, Pawnee, Apache, Comanche… and of course the Lakota Sioux. Remember Dances With Wolves? Yeah, this was THAT time period. Tatanka.

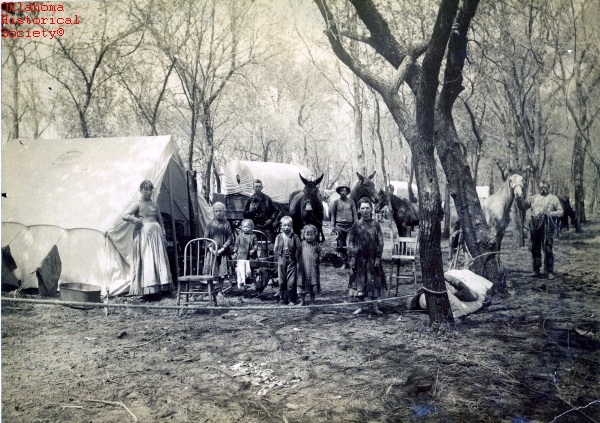

That made room for the U.S. to begin packing in other tribes, this time mostly from the Great Plains. The Cheyenne, Arapaho, Wichita, Kickapoo, Pawnee, Apache, Comanche… and of course the Lakota Sioux. Remember Dances With Wolves? Yeah, this was THAT time period. Tatanka.

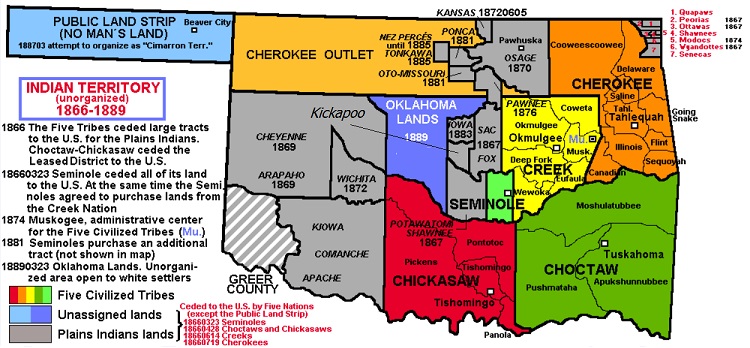

Gentlemen, meet Oklahoma – or, part of her, anyway. That ‘unassigned’ section there in the middle. I like this one allot (see what I did there?) but you don’t wanna end up holding her panhandle, I assure you.

Gentlemen, meet Oklahoma – or, part of her, anyway. That ‘unassigned’ section there in the middle. I like this one allot (see what I did there?) but you don’t wanna end up holding her panhandle, I assure you.

Consider Alyssa – a wonderful young lady in AP classes from a two-parent Methodist family. She works hard, makes good grades, stays out of any real trouble, and wants to be a neuroscientist. Obviously she deserves some credit for her accomplishments. She’s demonstrated great capability, and made good decisions.

Consider Alyssa – a wonderful young lady in AP classes from a two-parent Methodist family. She works hard, makes good grades, stays out of any real trouble, and wants to be a neuroscientist. Obviously she deserves some credit for her accomplishments. She’s demonstrated great capability, and made good decisions. Compare her to Dionne – another wonderful young lady, but one from very different circumstances. Her life might be happy enough, or it might be reality-show dysfunctional, but in any case does NOT unfold in the same universe as Alyssa’s. All of the rules are different and their experiences mutually exclusive.

Compare her to Dionne – another wonderful young lady, but one from very different circumstances. Her life might be happy enough, or it might be reality-show dysfunctional, but in any case does NOT unfold in the same universe as Alyssa’s. All of the rules are different and their experiences mutually exclusive. Anders is my Amerindian, although he might be Hispanic, or White, or Black, or whatever – there are racial issues wound up in these, but they’re not exclusive or always definitive. Many Amerindians had no interest in the Anglo-American value system or way of life, but they were forced to partake – and stakes were high if they failed. They lacked buy-in, but they also were denied good tools, seed, land, etc. It’s not much of a stretch to think a comparable state exists between many teenagers and whatever public school system holds them captive in 2015.

Anders is my Amerindian, although he might be Hispanic, or White, or Black, or whatever – there are racial issues wound up in these, but they’re not exclusive or always definitive. Many Amerindians had no interest in the Anglo-American value system or way of life, but they were forced to partake – and stakes were high if they failed. They lacked buy-in, but they also were denied good tools, seed, land, etc. It’s not much of a stretch to think a comparable state exists between many teenagers and whatever public school system holds them captive in 2015. You’re so thankful for Alyssa – students like her give you the energy to get through the day. But how often is Alyssa essentially rewarded for her upbringing and Dionne marginalized for not ‘working hard enough’? How angry does Anders make you even though he doesn’t really do anything to you other than not be taught? Zack’s an annoying little turd, but he’s passing and no one’s mad at you because of him so… whatever.

You’re so thankful for Alyssa – students like her give you the energy to get through the day. But how often is Alyssa essentially rewarded for her upbringing and Dionne marginalized for not ‘working hard enough’? How angry does Anders make you even though he doesn’t really do anything to you other than not be taught? Zack’s an annoying little turd, but he’s passing and no one’s mad at you because of him so… whatever.

It’s dangerous to project backwards regarding motivations and intentions, but it seems that even when public education was barely a thing, they realized it would soon become essential if their sons were to flourish in the next generation. I don’t know if they were worried about ‘personal fulfillment’ stuff as well, but I’m an idealist, so… let’s assume maybe they did.

It’s dangerous to project backwards regarding motivations and intentions, but it seems that even when public education was barely a thing, they realized it would soon become essential if their sons were to flourish in the next generation. I don’t know if they were worried about ‘personal fulfillment’ stuff as well, but I’m an idealist, so… let’s assume maybe they did.

Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops… Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them…

Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops… Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them… This is not my anti-capitalism rant. I’ll leave that to Tom Joad and his spirit moving among the hungry children and such. I’m more or less a Libertarian, but the Libertarian Ideal in MY interpretation requires a capable citizenry with actual options and real opportunity. It’s fine to support free will and full consequences for our actions, but to believe this and sleep at night we need something akin to a ‘equitable starting position’ or the proverbial ‘level playing field’.

This is not my anti-capitalism rant. I’ll leave that to Tom Joad and his spirit moving among the hungry children and such. I’m more or less a Libertarian, but the Libertarian Ideal in MY interpretation requires a capable citizenry with actual options and real opportunity. It’s fine to support free will and full consequences for our actions, but to believe this and sleep at night we need something akin to a ‘equitable starting position’ or the proverbial ‘level playing field’.  Ma was right – no one knew what it was gonna be like. Rose was pregnant, so that’s literary, and Connie – ironically – wasn’t far off track in terms of how the future was going to work for those able to claim it. As in, NOT the Joads.

Ma was right – no one knew what it was gonna be like. Rose was pregnant, so that’s literary, and Connie – ironically – wasn’t far off track in terms of how the future was going to work for those able to claim it. As in, NOT the Joads.