NOTE: I’m revising and reorganizing much of the content from “Well, OK Then” as part of an overall effort to ‘clean up’ this site. This post is one of those newer, better versions of something previously shared.

Chief John Ross was a “mixed-blood” Cherokee who nevertheless became the best-known and arguably the most effective tribal leader of his generation. His supporters tended to lean traditional – they were conservative, and old-school – wanting little or no contact with whites and uninterested in their version of “progress.”

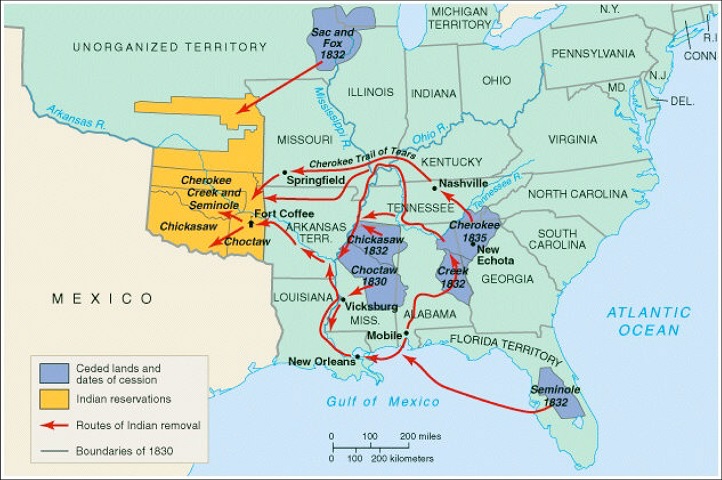

Because he would not agree to voluntary removal, the U.S. found others in the tribe who would. They plied them with land and money and the argument that this was going to happen one way or the other – so they might as well make it as painless as possible. The signers of the Treaty of New Echota (1835) violated the most sacred of Cherokee laws while lacking the status to even speak for the tribe to begin with.

Ross was not impressed, and wrote this to Congress on September 28th, 1836:

It is well known that for a number of years past we have been harassed by a series of vexations, which it is deemed unnecessary to recite in detail, but the evidence of which our delegation will be prepared to furnish…

{A} contract was made by the Rev. John F. Schermerhorn, and certain individual Cherokees, purporting to be a “treaty, concluded at New Echota, in the State of Georgia, on the 29th day of December, 1835, by {U.S. Commissioners} and the chiefs, headmen, and people of the Cherokee tribes of Indians.” A spurious Delegation, in violation of a special injunction of the general council of the nation, proceeded to Washington City with this pretended treaty, and by false and fraudulent representations supplanted in the favor of the Government the legal and accredited Delegation of the Cherokee people, and obtained for this instrument, after making important alterations in its provisions, the recognition of the United States Government.

And now it is presented to us as a treaty, ratified by the Senate, and approved by the President, and our acquiescence in its requirements demanded, under the sanction of the displeasure of the United States, and the threat of summary compulsion, in case of refusal…

Chief Ross knew his facts and his audience. He wastes little energy on extraneous issues or the details of past problems. He goes straight to what is essentially contract law – and accuses the U.S. of making a fraudulent deal. Abusing Indians might not have been all that un-American, but bogus contracts were certainly close.

By the stipulations of this instrument, we are despoiled of our private possessions, the indefeasible property of individuals. We are stripped of every attribute of freedom and eligibility for legal self-defence. Our property may be plundered before our eyes; violence may be committed on our persons; even our lives may be taken away, and there is none to regard our complaints. We are denationalized; we are disfranchised.

Ross doesn’t talk about the land, or his people’s culture, etc. He doesn’t badmouth the individuals who signed the Treaty of New Echota, beyond indicating they had no right to do so.

He instead highlights elements of the situation which were more likely to resonate with his audience. After establishing the invalidity of the treaty, he argues that it violates their property rights. Few things were more sacred to real Americans. John Locke argued that protection of property – which he defined as “life, liberty, and estate” – was the sole function of government. Jefferson replaced “estate” with “pursuit of happiness,” but lest there be any confusion, the Fifth Amendment specifically defends “life, liberty, and property” from government intrusion without “due process.”

Which this, clearly, was not.

Ross then throws in freedom (liberty), the right to defend yourself before the law, and personal safety. Those are the big three – life, liberty, and your stuff. They’re held together by the underlying assumption that such “natural rights” are every man’s refuge in a nation built on such ideals.

It’s a brilliant approach. He has facts and reasoning on his side. Unfortunately, facts and reasoning weren’t going to decide this issue – the results were determined before he’d even bought his ticket. The U.S. was concerned only with rhetorical cover at this point. The Treaty gave them that – they knew damn well it wasn’t legitimate… they just didn’t care.

Ross does speak to the ethical abhorrence of the situation, albeit briefly:

We are deprived of membership in the human family! We have neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own. And this is effected by the provisions of a compact which assumes the venerated, the sacred appellation of treaty.

We are overwhelmed! Our hearts are sickened, our utterance is paralized, when we reflect on the condition in which we are placed, by the audacious practices of unprincipled men, who have managed their stratagems with so much dexterity as to impose on the Government of the United States, in the face of our earnest, solemn, and reiterated protestations.

Then, like a good five-paragraph essay, he repeats his main point by way of conclusion.

The instrument in question is not the act of our Nation; we are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people. The makers of it sustain no office nor appointment in our Nation, under the designation of Chiefs, Head men, or any other title, by which they hold, or could acquire, authority to assume the reins of Government, and to make bargain and sale of our rights, our possessions, and our common country.

And we are constrained solemnly to declare, that we cannot but contemplate the enforcement of the stipulations of this instrument on us, against our consent, as an act of injustice and oppression, which, we are well persuaded, can never knowingly be countenanced by the Government and people of the United States…

{We} appeal with confidence to the justice, the magnanimity, the compassion, of your honorable bodies, against the enforcement, on us, of the provisions of a compact, in the formation of which we have had no agency.

It’s almost like he thinks governmental power is derived through the consent of the governed. “No removal without representation!”

Not really very catchy, I guess.

Ross’s complaints would fall on deaf ears. The powers-that-be had already undermined Cherokee sovereignty via two Supreme Court cases. In the first one, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Court refused to hear the actual case – a complaint by the Cherokee that the State of Georgia kept passing laws which infringed on their guaranteed sovereignty within their own boundaries. The Court determined that the Cherokee certainly weren’t American citizens, but neither were they exactly a sovereign nation – at least not any more. Their relationship with the U.S. was like that of a “ward to its guardian.”

In other words, they were Dick Grayson to America’s Bruce Wayne. And they would never turn 18 in the eyes of the law.

The second case was brought by a white guy – a missionary to the Cherokee by the name of Samuel Worcester. Georgia had passed a law requiring non-Cherokee to get permission from the state before going onto Cherokee land – without bothering to include the Cherokee in the process. Worcester ignored the prohibition and kept doing his thing, and was arrested and jailed. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court declared that only the federal government could deal with the tribes – Georgia couldn’t do that.

The decision was considered a victory for the Cherokee, but it didn’t really change anything. President Jackson is often quoted as having said “Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it!” There’s no record of such as statement, but it was certainly consistent with Jackson’s general attitude towards the Court, the Natives, and anyone else who disagreed with him about anything ever.

The Court’s decision did not, in any case, shape or limit anything Jackson or Congress chose to do in relation to the Tribes thereafter. That the other two branches could ignore such a decision with impunity was a pretty clear indication of the status of a bunch of “savages” vs. the segment of “all men” actually represented.

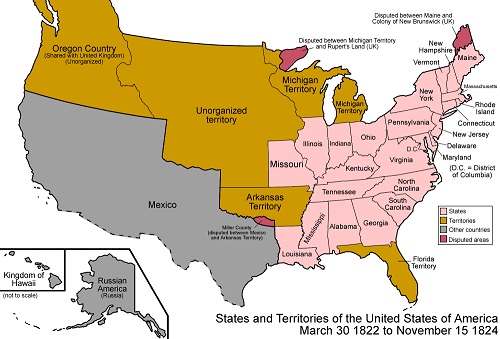

So it’s 1836 and the Treaty of New Echota has been signed, by influential Cherokee if not by those actually authorized to do so. Stand Watie, Major Ridge (it’s a first name, not a title or rank), Elias Boudinot, and others, led nearly 10,000 of their countrymen to Indian Territory.

This was NOT the “Trail of Tears.” This was the “voluntary” part, more or less. It was several years before the remaining Cherokee were rounded up by force and driven to join their people far to the west. The suffering on this journey is well-documented and not one of the prouder moments in U.S. History.

The later arrivals, after so many months of death and suffering, were not particularly happy to see their earlier counterparts, already established in what would later be known as “Oklahoma.” The signing away of their lands wasn’t received much differently than if they’d offered up a few hundred of their virgin daughters for debauchery and eventual beheading. It was not only wrong, it was specifically against Cherokee law and carried the strongest possible consequences.

Several of the leaders of the “Treaty Party,” whose names had validated the removal treaty, were assassinated on the same night, not long after the remaining Cherokee arrived. It’s assumed that John Ross was behind this, or at the very least was aware of it before it happened, but no one knows for sure.

Whatever the justice or injustice of this decision, it isn’t the sort of thing that smooths transitions or promotes unity. The tensions weren’t new – full-bloods already tended to be pretty conservative while mixed-bloods were far more receptive to change and some elements of white culture – but this didn’t help. These same divisions will reappear in less than a generation when the white guys start dragging the Five Civilized Tribes into their “Civil War.”

It’s worth noting that the time period between Indian Removal in the 1830s and the start of the Civil War in 1861 is considered something of a “Golden Age” for the Five Civilized Tribes. This might be partly a sort of historical “spin” to offset white guilt over removal, but it’s not without merit.

The Tribes had brought their Black slaves with them to Indian Territory. The story of slavery among the Five Civilized Tribes is a whole other tale, but the short version is that by and large, slavery among the Tribes was far less onerous than that practiced by white southerners. Slavery is still slavery, of course, but it generally lacked the malice and violence brought to mind when discussing early American history.

For a quarter of a century, then, the ‘Red Man’ and the ‘Black Man’ lived in relative peace and quiet in Indian Territory. They rebuilt their governments, their schools, their presses, their churches, and their lives. They learned to adapt to the realities of this new territory and enjoyed a rare generation free of white interference.

Until that war thing, at least. Once that started, it was all pretty much downhill for the Cherokee and every other “civilized” tribe. For good.

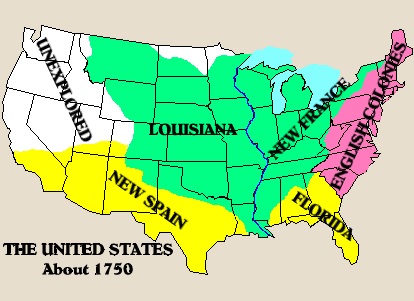

The first European nation to lay claim to what is now Oklahoma was Spain, via wanderings sent forth from New Spain – what today is Mexico.

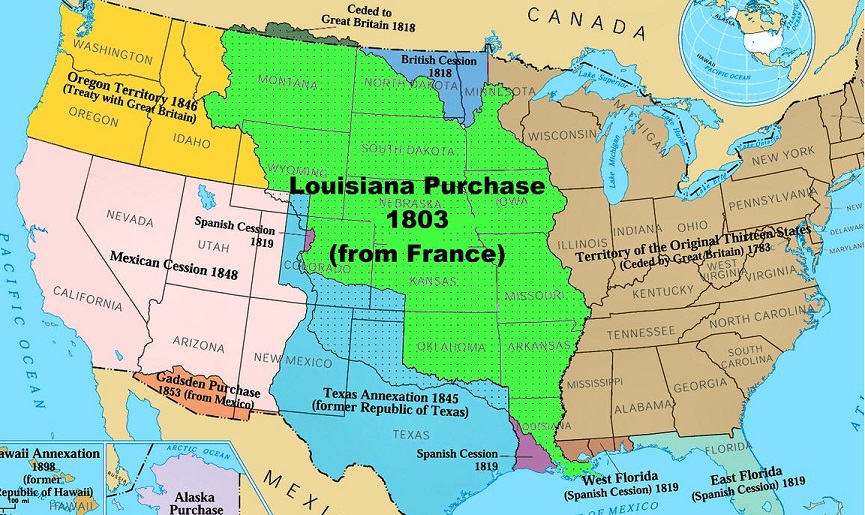

The first European nation to lay claim to what is now Oklahoma was Spain, via wanderings sent forth from New Spain – what today is Mexico.  In any case, the Treaty of Paris (1763) transferred proud ownership of all this flat, red dirt to the British, despite a secret agreement handing it over to Spain only a year before. It says something about the status of pre-settlement Oklahoma that Spain didn’t even fuss over this double-dealing; their primary concern involved other territories included in that exchange.

In any case, the Treaty of Paris (1763) transferred proud ownership of all this flat, red dirt to the British, despite a secret agreement handing it over to Spain only a year before. It says something about the status of pre-settlement Oklahoma that Spain didn’t even fuss over this double-dealing; their primary concern involved other territories included in that exchange.  Fine. We’ll waive our *mumble* wheat for someone *murmur* can appreciate *grouse* land we belong to is grandma’s crusty *obsenitiesandbitterness*.

Fine. We’ll waive our *mumble* wheat for someone *murmur* can appreciate *grouse* land we belong to is grandma’s crusty *obsenitiesandbitterness*. But the U.S. found it necessary to violate a number of its own fundamental values and laws in order to kick FIVE distinct nations out of an area roughly the size of THREE entire states. They did so at enormous cost to themselves and unforgivable loss of life to those removed. This was driven by something bigger than gold, something fundamental to an expanding nation.

But the U.S. found it necessary to violate a number of its own fundamental values and laws in order to kick FIVE distinct nations out of an area roughly the size of THREE entire states. They did so at enormous cost to themselves and unforgivable loss of life to those removed. This was driven by something bigger than gold, something fundamental to an expanding nation.  There we go – the “besides, it’s good for them” defense. We used a variation of this to justify slavery, you may recall – saving all those crazy Africans from their ooga-booga religions and cannibalism and such, freeing them up to play banjos around the fire and partake of the finest Christian civilization.

There we go – the “besides, it’s good for them” defense. We used a variation of this to justify slavery, you may recall – saving all those crazy Africans from their ooga-booga religions and cannibalism and such, freeing them up to play banjos around the fire and partake of the finest Christian civilization.  Jackson may be overdoing it a bit, even by the standards of the day. His primary purpose was most likely not to convert anyone adamantly opposed, but to assuage any guilt on the part of those already looking for an excuse. That’s why we talk about “audience” and “reason” when we do document analysis, kids – dead white guys can be sneaky.

Jackson may be overdoing it a bit, even by the standards of the day. His primary purpose was most likely not to convert anyone adamantly opposed, but to assuage any guilt on the part of those already looking for an excuse. That’s why we talk about “audience” and “reason” when we do document analysis, kids – dead white guys can be sneaky.