History, by definition, is written down. This is not an knock against archeology, anthropology, oral histories, or any other efforts to unravel the past – it’s just a definition.

History, by definition, is written down. This is not an knock against archeology, anthropology, oral histories, or any other efforts to unravel the past – it’s just a definition.

Consequently, prior to European exploration, everything we know about what is now Oklahoma is technically “pre-history.” This is important because I’m about to insist that the History of Oklahoma began in 1540 with the arrival of a conquistador by the name of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, and I don’t want to sound, you know – Eurocentric or dismissive of pre-literate peoples or anything. I like to think of myself as quite culturally sensitive and stuff.

There are other places we could begin, of course. Unlike with people, the “birth” of Oklahoma is not an objectively established event. We could place its beginnings way back with the earliest fossil records, although that leaves us with a rather broad range of possible dates – as in, “the earliest Oklahomans settled the land sometime between 50,000 and 100,000,000 years ago…”

So, that’s unfulfilling.

Indian Removal (1830s) is arguably the beginning of Oklahoma as we now know it, despite the massive changes which followed only a generation later. That’s not where we begin in class, but it’s where we slow down enough to start paying attention.

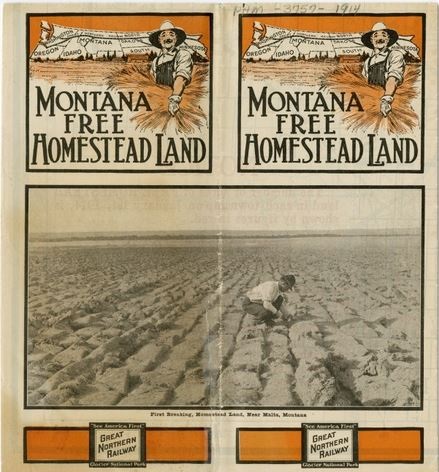

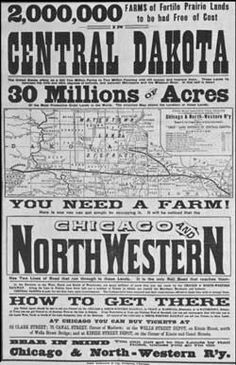

The first Land Run (1889) is certainly one of the more colorful events in our collective past, and far less depressing than most – at least if you don’t look too closely. This is when the first ‘Oklahoma’ lands were legally opened to white settlement, so claiming it as our “day of birth” has a certain logic to it. Then again, that would mean coming to peace with the suggestion it’s not really history until white people show up.

The first Land Run (1889) is certainly one of the more colorful events in our collective past, and far less depressing than most – at least if you don’t look too closely. This is when the first ‘Oklahoma’ lands were legally opened to white settlement, so claiming it as our “day of birth” has a certain logic to it. Then again, that would mean coming to peace with the suggestion it’s not really history until white people show up.

Which I can’t.

Statehood (1907) would be an obvious choice, I suppose – but again with the white guys. Economically one might argue that for all intents and purposes Oklahoma truly began with the oil boom, another “date range” event – although surely we could agree the Glenn Pool (1905) was the catalyst for all the rest. But the 20th century? Really? That would make us babies, historically speaking.

So I choose to be literal and insist that the History of Oklahoma began in 1540 with the arrival of a conquistador by the name of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado. He led an expedition which wandered through part of what is now far-western Oklahoma. Significantly, for our purposes, he and some of those with him left written records of their thoughts and experiences as they traveled – the first recorded “history” of the area.

So I choose to be literal and insist that the History of Oklahoma began in 1540 with the arrival of a conquistador by the name of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado. He led an expedition which wandered through part of what is now far-western Oklahoma. Significantly, for our purposes, he and some of those with him left written records of their thoughts and experiences as they traveled – the first recorded “history” of the area.

The Spanish may have been the first to write about this little section of the universe, but they were hardly the first to encounter it. Various Amerindians had lived in or traveled across the Great Plains for centuries – maybe millennia. There were hundreds of different tribal identifications, and a far greater variety of cultures than we usually acknowledge. It’s really quite fascinating, if you’re into that sort of thing.

And they all came from somewhere else.

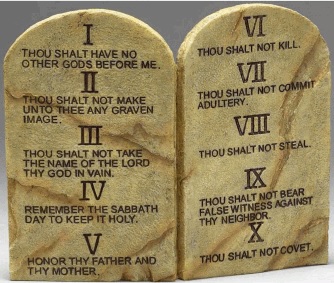

Based on the evidence we have now, mankind – such as it is – started far away from here. If the Lord created Adam and Eve and placed them in a tangible Garden of Eden, He did so WAY across the world – probably in Iran or thereabouts. If man evolved from single-celled protozoa, into a fish, then a goat, then a monkey, etcetera, he did so WAY across the world – most likely the Middle East and/or Northern Africa.

There was spawning and diffusion, like there always is, and at some point a bunch of them walked across the Bering Strait (the ancient land bridge between Russia and Alaska) and spread across the Western Hemisphere. It would have taken a while. There may have been multiple cultures arriving over time, or they may have diversified over the centuries once here. In any case, the Amerindian tribes covering this half of the world before the Europeans showed up were quite a diverse bunch.

Again – good stuff if you’re into that sort of thing and wish to study it further. People do.

One of the big questions among American historians is just how many Amerindians were here before Columbus showed up and brought all of Europe as his ‘plus one.’ War and disease and such killed, well… a bunch of the native population, but whether that means a quarter, a third, or ninety-nine percent is in serious dispute.

The answer matters, and not merely for statistical precision – historians are still trying to figure out if the arrival of white guys simply sped the decline of cultures who’d have eventually evolved or vanished anyway, or whether 1492 marked the onset of not-entirely-unintentional genocide. It’s an ethical question as much as a historical, political, or social issue.

Not that Coronado was wrestling with such abstractions in 1540.

It had been less than a half-century since Columbus sailed the ocean blue and stumbled across this little roadblock to India. The British seemed in no hurry to settle the new continent – Jamestown was established in 1607, Plymouth in 1620, and the Puritans started arriving around 1630. Spain, however, wasted little time making their presence felt across Central America and Southwestern North America.

In 1520, Hernán Cortés led the overthrow of the Aztec Empire in what is now Mexico. By 1532, Francisco Pizarro helped bring about the destruction of the Incas in Peru. In both cases, Spanish conquistadors had discovered complex civilizations and unmeasurable wealth. In both cases, the reality of their experiences dramatically exceeded rumors or expectations.

It was thus not particularly ridiculous for Coronado to go looking for untold riches or follow rumors of lavish cities inhabited by wondrous people. He set out in February of 1540 to do just that.

Conquistadors didn’t like to do anything on a modest scale, so Coronado took along 400 armed men and over a thousand Mexican-Indian “allies”. That many people meant livestock, food wagons, and innumerable other supplies in tow, making for quite the logistical monstrosity.

His exact route is debatable, but he seems to have started north from what is now Mexico and traveled into New Mexico and/or Arizona in search of the “Seven Cities of Cibola.” He got into a few scraps with the locals, but his journey was otherwise unexciting until he encountered a young man the Spanish quickly nicknamed “The Turk.”

RELATED POST: Turkin’ Back and Forth

RELATED POST: Coronado’s Letter (“What I AM Sure Of Is This…”)

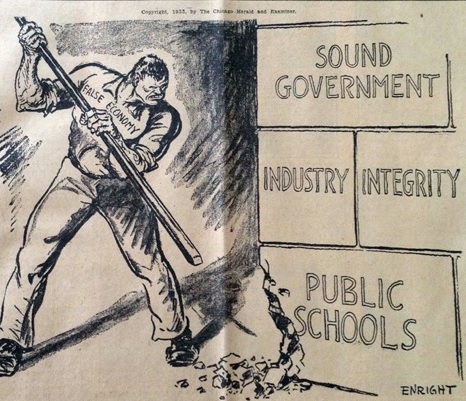

This mindset was a precursor to the Progressive Era and its Amendments – the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th. Basically, there was a concern that government at all levels was too far removed from ‘the people.’ Various reforms gave voters more direct input on who was elected and what changes could be made – recalls, referendums, etc.

This mindset was a precursor to the Progressive Era and its Amendments – the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th. Basically, there was a concern that government at all levels was too far removed from ‘the people.’ Various reforms gave voters more direct input on who was elected and what changes could be made – recalls, referendums, etc.  That’s important in a decade during which we repeatedly introduce, debate, and occasionally pass state laws which are undeniably doomed once challenged in the courts. We spend hundreds of thousands of dollars fighting for the right to return to the 19th century.

That’s important in a decade during which we repeatedly introduce, debate, and occasionally pass state laws which are undeniably doomed once challenged in the courts. We spend hundreds of thousands of dollars fighting for the right to return to the 19th century.

This has caused untold grief since oil prices crashed. Due to previously passed legislation, the tax cuts for top earners across the state keep waterfalling at preplanned intervals, despite little evidence they’re producing all of that ‘prosperity’ used to justify them in the first place. When anyone suggests perhaps we could slow down on that a bit until we’re no longer feeding on the weak and the young, our legislature cries with hands upraised – “What can we do?! It’s… it’s… AGAINST THE RULES!”

This has caused untold grief since oil prices crashed. Due to previously passed legislation, the tax cuts for top earners across the state keep waterfalling at preplanned intervals, despite little evidence they’re producing all of that ‘prosperity’ used to justify them in the first place. When anyone suggests perhaps we could slow down on that a bit until we’re no longer feeding on the weak and the young, our legislature cries with hands upraised – “What can we do?! It’s… it’s… AGAINST THE RULES!”

We’d like to tweak the A-F School District Shaming System by juggling a few phrases, and ohyeahbytheway – THIS IS AN EMERGENCY AND IMMEDIATELY NECESSARY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE PUBLIC PEACE, HEALTH, AND SAFETY.

We’d like to tweak the A-F School District Shaming System by juggling a few phrases, and ohyeahbytheway – THIS IS AN EMERGENCY AND IMMEDIATELY NECESSARY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE PUBLIC PEACE, HEALTH, AND SAFETY.

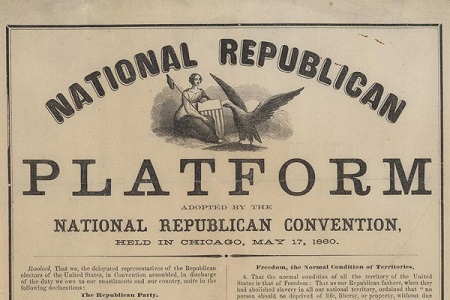

When the Republican Party became a thing in the 1850s, it pushed two basic tenets: (1) Slavery is bad, and (2) Polygamy is bad. The second was clearly in response to the Latter Day Saints.

When the Republican Party became a thing in the 1850s, it pushed two basic tenets: (1) Slavery is bad, and (2) Polygamy is bad. The second was clearly in response to the Latter Day Saints.

Look at that. We DID know about the Reconstruction Amendments way back then. Wonder how we lost THAT collective awareness…

Look at that. We DID know about the Reconstruction Amendments way back then. Wonder how we lost THAT collective awareness… That’s perfectly consistent with American ideals. Jefferson may have changed “life, liberty, and property” to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” but the original phrase is used often enough elsewhere to leave little doubt regarding intent.

That’s perfectly consistent with American ideals. Jefferson may have changed “life, liberty, and property” to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” but the original phrase is used often enough elsewhere to leave little doubt regarding intent.

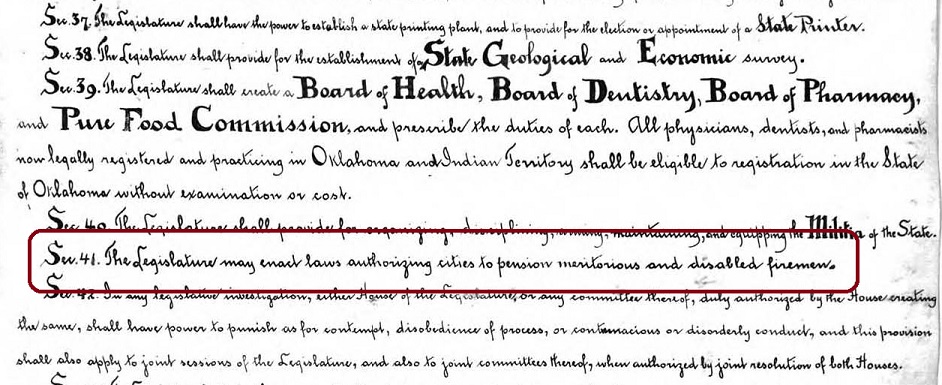

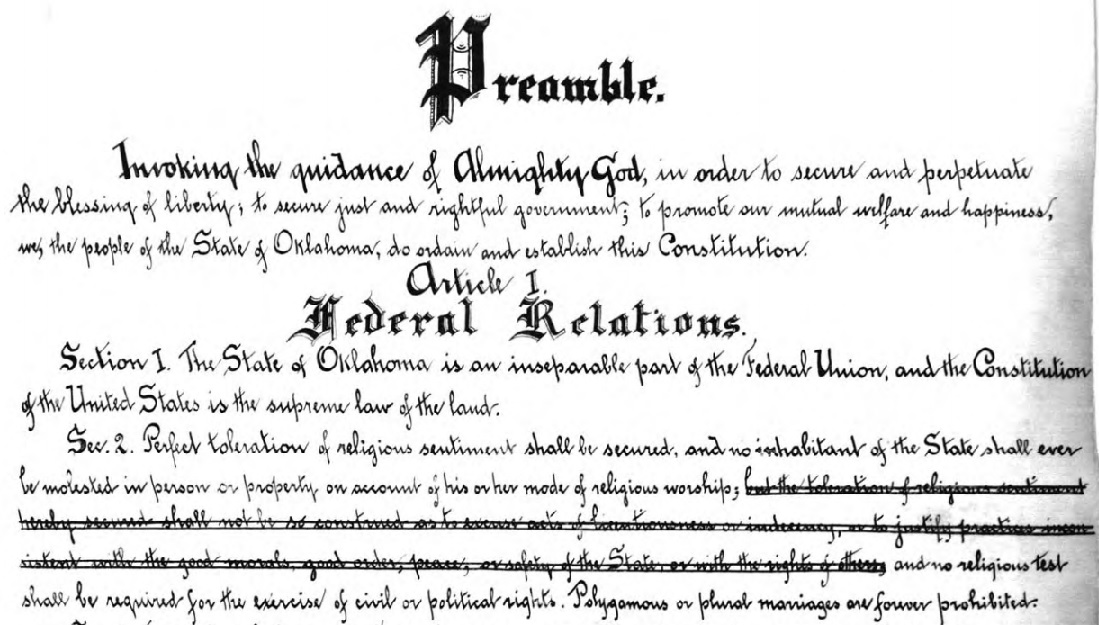

The U.S. Constitution, including all 27 Amendments, takes up less than 14 pages as a Word document with normal fonts and margins. The Oklahoma Constitution, in contrast, takes 221 pages.

The U.S. Constitution, including all 27 Amendments, takes up less than 14 pages as a Word document with normal fonts and margins. The Oklahoma Constitution, in contrast, takes 221 pages. If you know anything about Alfalfa Bill, this is either painfully ironic or ridiculously amusing. Even if you don’t, the founding of Oklahoma on ‘modern thought’ and the ‘highest estimate of intelligence and progress’ should produce some sort of reaction. Perhaps even involuntary regurgitation.

If you know anything about Alfalfa Bill, this is either painfully ironic or ridiculously amusing. Even if you don’t, the founding of Oklahoma on ‘modern thought’ and the ‘highest estimate of intelligence and progress’ should produce some sort of reaction. Perhaps even involuntary regurgitation.  In 1906, the U.S. Congress passed the “Oklahoma Enabling Act,” providing for a single state to be formed from Oklahoma and Indian Territories. Each half sent delegates – mostly Democrats – and William H. Murray was – big shocker here – elected president of this new Constitutional Convention.

In 1906, the U.S. Congress passed the “Oklahoma Enabling Act,” providing for a single state to be formed from Oklahoma and Indian Territories. Each half sent delegates – mostly Democrats – and William H. Murray was – big shocker here – elected president of this new Constitutional Convention.

Early in the document (Article II), the drafters enumerated thirty-three rights in the Bill of Rights Article. This was followed by the article on suffrage. The right to vote, except in school board elections, was restricted to males. (The constitution was amended giving women the right to vote in 1918, two years before the U.S. Constitution was amended giving women the right to vote.)

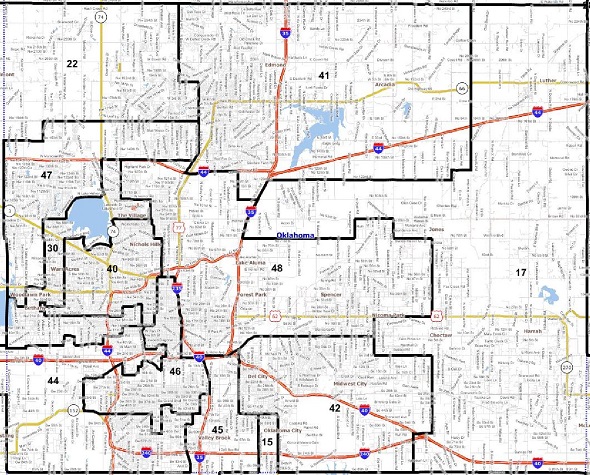

Early in the document (Article II), the drafters enumerated thirty-three rights in the Bill of Rights Article. This was followed by the article on suffrage. The right to vote, except in school board elections, was restricted to males. (The constitution was amended giving women the right to vote in 1918, two years before the U.S. Constitution was amended giving women the right to vote.)  That thing where so many positions are elected rather than appointed is creating headaches even today. It was an age of ‘let the people decide’, creating rules not conducive to our love of ‘voting the party ticket’ for everything from Governor to Dog Catcher to Insurance Commissioner.

That thing where so many positions are elected rather than appointed is creating headaches even today. It was an age of ‘let the people decide’, creating rules not conducive to our love of ‘voting the party ticket’ for everything from Governor to Dog Catcher to Insurance Commissioner.

That last part is what’s been so-often cited to explain why we simply CAN’T slow down the almost complete elimination of taxes for anyone wearing expensive suits and smoking cigars in darkened back rooms. Once the process is begun, the argument goes, any reduction of the destruction amounts to a ‘tax increase’.

That last part is what’s been so-often cited to explain why we simply CAN’T slow down the almost complete elimination of taxes for anyone wearing expensive suits and smoking cigars in darkened back rooms. Once the process is begun, the argument goes, any reduction of the destruction amounts to a ‘tax increase’. William Jennings Bryan told the members of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention that they had borrowed the best provisions of the existing state and national constitutions and had, in the process, created the best constitution ever written. Scholars who believe that brief constitutions devoid of policy make the best constitutions would disagree with Bryan’s assessment.

William Jennings Bryan told the members of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention that they had borrowed the best provisions of the existing state and national constitutions and had, in the process, created the best constitution ever written. Scholars who believe that brief constitutions devoid of policy make the best constitutions would disagree with Bryan’s assessment.