Mrs. Chesnut has been recording for posterity the events surrounding the so-called “Battle of Fort Sumter.” Except she’s mostly not.

Mrs. Chesnut has been recording for posterity the events surrounding the so-called “Battle of Fort Sumter.” Except she’s mostly not.

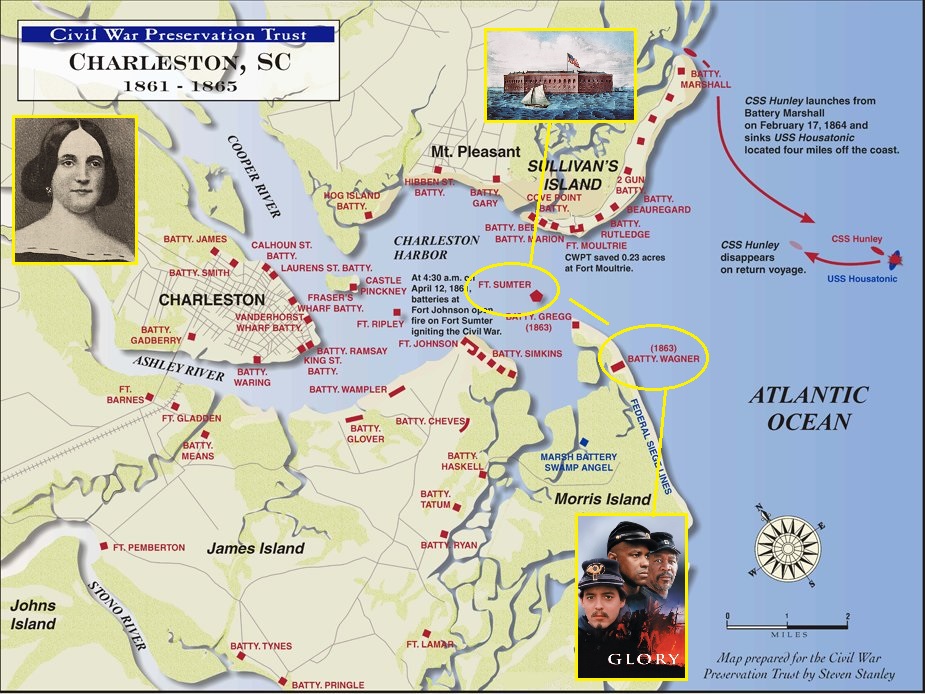

Louisa Hamilton came here now. This is a sort of news center. Jack Hamilton, her handsome young husband, has all the credit of a famous battery, which is made of railroad iron. Mr. Petigru calls it the ‘boomerang,’ because it throws the balls back the way they came; so Lou Hamilton tells us.

The ‘boomerang’ bit is a brag by Mrs. Hamilton on her husband‘s artillery unit – they not only hold their ground when taking incoming fire, they gather the cannonballs fired at them and send them back. Boo-yah!

How much you wanna bet Mrs. H. works that into conversation one way or the other about every three minutes?

During her first marriage, she had no children; hence the value of this lately achieved baby.

Historical documents of a personal nature can be difficult – especially for students – because tone is everything. Miss a little flirting, or sarcasm, or other emoticon-deficient vibe, and you can misread a source completely.

Mrs. Chesnut is kind enough to write on both levels simultaneously – the obvious, smiling appreciation for a friend’s long-awaited offspring, and – unless I’m projecting – a little wry commentary on Louisa’s mothering as well.

It might even be cruel.

To divert Louisa from the glories of “the Battery,” of which she raves, we asked if the baby could talk yet. “No, not exactly, but he imitates the big gun when he hears that. He claps his hands and cries ‘Boom, boom.'”

Her mind is distinctly occupied by three things: Lieutenant Hamilton, whom she calls “Randolph,” the baby, and the big gun, and it refuses to hold more…

*snort*

I do not wonder at Louisa Hamilton’s baby; we hear nothing, can listen to nothing; boom, boom goes the cannon all the time. The nervous strain is awful, alone in this darkened room. “Richmond and Washington ablaze,” say the papers – blazing with excitement. Why not? To us these last days’ events seem frightfully great.

That Chesnut always returns to the sincere – the experience – anchors her prose in a way mere observation or fiction could not. Her ability to grab descriptive slices of people and events and weave them in so transparently makes this something more alive than most find mere history to be.

That Chesnut always returns to the sincere – the experience – anchors her prose in a way mere observation or fiction could not. Her ability to grab descriptive slices of people and events and weave them in so transparently makes this something more alive than most find mere history to be.

But that’s what makes this real history.

The war, the guns, the actions, the results – facts mattered, and always will. But people, having experiences, and making choices, and feeling feels… in the end, that‘s usually what produces the wars and drives the actions. Like Anne Frank in her attic or Bridget Jones navigating high society in London*, that rare opportunity to zoom in and inhabit the past through the eyes and experiences of another – that’s why we love history.

It gets even better.

April 13th. – Nobody has been hurt after all. How gay we were last night…

Yes, half of my students are 14-year old boys. This line is always a thing.

Fort Sumter has been on fire. Anderson has not yet silenced any of our guns. So the aides, still with swords and red sashes by way of uniform, tell us. But the sound of those guns makes regular meals impossible. None of us go to table. Tea-trays pervade the corridors going everywhere. Some of the anxious hearts lie on their beds and moan in solitary misery. Mrs. Wigfall and I solace ourselves with tea in my room. These women have all a satisfying faith. “God is on our side,” they say. When we are shut in Mrs. Wigfall and I ask “Why?” “Of course, He hates the Yankees, we are told. You’ll think that well of Him.”

“A satisfying faith” – once again, understated layers of meaning. Chesnut doesn’t directly comment, she portrays – with precision. I think she’s aware of us, all these years later, reading her through this… ‘documentation’ of events. Do you feel her Mona Lisa smirk on us?

“A satisfying faith” – once again, understated layers of meaning. Chesnut doesn’t directly comment, she portrays – with precision. I think she’s aware of us, all these years later, reading her through this… ‘documentation’ of events. Do you feel her Mona Lisa smirk on us?

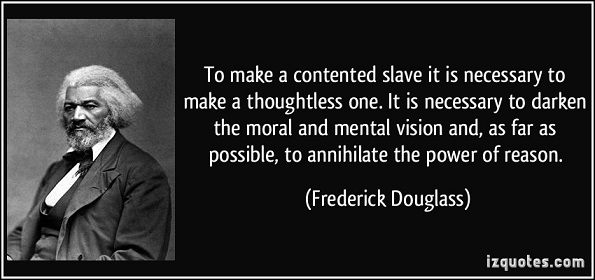

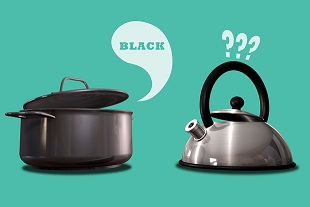

Not by one word or look can we detect any change in the demeanor of these negro servants. Lawrence sits at our door, sleepy and respectful, and profoundly indifferent. So are they all, but they carry it too far. You could not tell that they even heard the awful roar going on in the bay, though it has been dinning in their ears night and day. People talk before them as if they were chairs and tables. They make no sign. Are they stolidly stupid? or wiser than we are; silent and strong, biding their time?

Southern nobility lived with themselves as slave-owners largely by learning not to ‘see’ those they enslaved. Perhaps overseers or smaller property owners were all too aware of what they were doing to real live people, but the elite seem to have largely trained themselves to give wide berth to troubling thoughts.

Chesnut’s diary resonates, however, not only from her poignant word choices, but her willingness to watch, and listen, in the first place. She is fully present, and not afraid to see what she sees. We should do so well.

Anyone could have made this observation – it’s glaring, once noted. People have an amazing capacity, though, to see what we wish to see and discard the rest. Whether slaves, dust, quiet students, personal faults, or moonwalking bears, our filters are really something else. We know this, but usually do a pretty good job ignoring this about ourselves as well. Ironic, right?

So tea and toast came; also came Colonel Manning, red sash and sword, to announce that he had been under fire, and didn’t mind it. He said gaily: “It is one of those things a fellow never knows how he will come out until he has been tried. Now I know I am a worthy descendant of my old Irish hero of an ancestor, who held the British officer before him as a shield in the Revolution, and backed out of danger gracefully.” We talked of St. Valentine’s eve, or the maid of Perth, and the drop of the white doe’s blood that sometimes spoiled all…

The standard American History book will tell you the South was overconfident after First Bull Run, etc. I’d argue Colonel Manning and his ilk were way ahead of the crowd on this one.

The standard American History book will tell you the South was overconfident after First Bull Run, etc. I’d argue Colonel Manning and his ilk were way ahead of the crowd on this one.

It’s still all a play, a fantastic story, to those involved at this stage. This is not something you’ll hear from men a year or two later in this war. Some will look back and shake their heads with a dark chuckle that they’d ever thought such things.

Fort Sumter surrendered, and the war was officially begun. The next major action will be a bit better planned – although not by much. At First Bull Run, young men will actually be injured. Many will die. But not yet.

April 20, 1861. – Home again at Mulberry. In those last days of my stay in Charleston I did not find time to write a word… I have been sitting idly to-day looking out upon this beautiful lawn, wondering if this can be the same world I was in a few days ago. After the smoke and the din of the battle, a calm.

Indeed.

* Just seeing if you were paying attention.

RELATED POST: Intermission: Mary Boykin Chesnut’s Diary, Part One

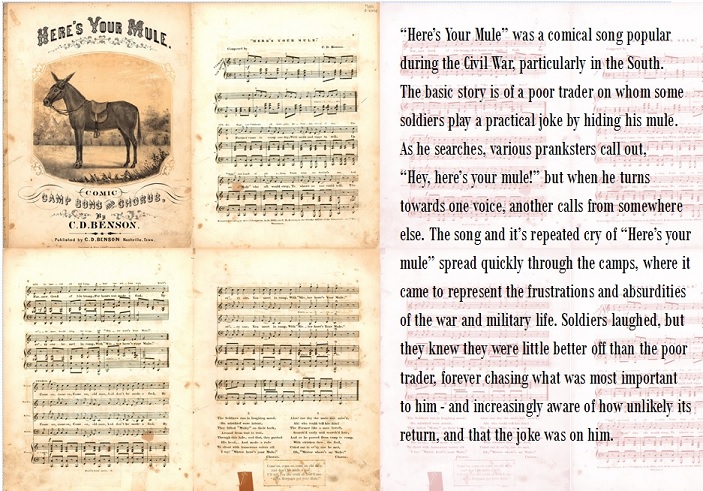

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part One – North vs. South

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part Two – Slavery & Sinners

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part Three – That Sure Was Sumter

Mary Boykin Chesnut was a Southern lady in the purest tradition, born into South Carolina’s political nobility and educated at one of the finest boarding schools in Charleston. Her husband was the son of a successful plantation owner and an upwardly mobile politico himself.

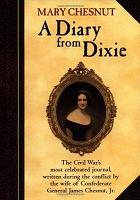

Mary Boykin Chesnut was a Southern lady in the purest tradition, born into South Carolina’s political nobility and educated at one of the finest boarding schools in Charleston. Her husband was the son of a successful plantation owner and an upwardly mobile politico himself.  The diary of Mrs. Chesnut is one of the essential primary sources of the Civil War, and still readily available if you’re interested. It’s quite accessible to the casual reader – you won’t even know you’re learning history, I promise.

The diary of Mrs. Chesnut is one of the essential primary sources of the Civil War, and still readily available if you’re interested. It’s quite accessible to the casual reader – you won’t even know you’re learning history, I promise.  Never has a better case been made for teaching reading and writing, although her keen observations on human nature are perhaps harder to mandate.

Never has a better case been made for teaching reading and writing, although her keen observations on human nature are perhaps harder to mandate.  “Men were audaciously wise and witty.” What a marvelous phrase. It sounds like the Mad Hatter’s tea party, but instead of pure chaos, her description is redolent of forced fearlessness and social gilding. F. Scott Fitzgerald has nothing on the wealthy belle when it comes to writing dinner parties.

“Men were audaciously wise and witty.” What a marvelous phrase. It sounds like the Mad Hatter’s tea party, but instead of pure chaos, her description is redolent of forced fearlessness and social gilding. F. Scott Fitzgerald has nothing on the wealthy belle when it comes to writing dinner parties.  While the rest of the city – and, by proxy, the South – celebrates the opening rounds of what will no doubt prove a majestic little melee, one anonymous voice just out of view notices that they’re firing land weapons at a fort designed to withstand attack by foreign navies.

While the rest of the city – and, by proxy, the South – celebrates the opening rounds of what will no doubt prove a majestic little melee, one anonymous voice just out of view notices that they’re firing land weapons at a fort designed to withstand attack by foreign navies.

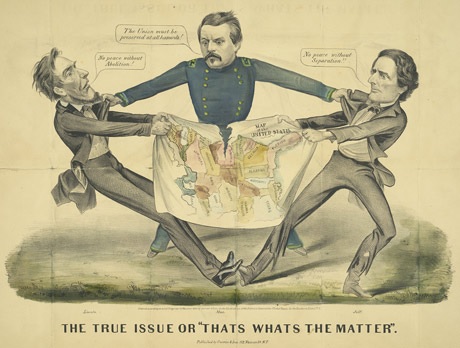

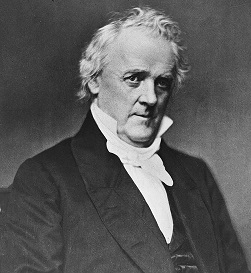

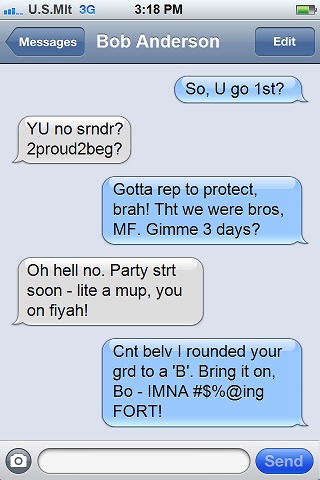

President Buchanan made a few token efforts to resupply the fort, but otherwise followed his famous “stall until it’s Lincoln’s problem” strategy – pretty much his approach to everything between November 1860 and March 1861. Lincoln took office to discover he had less than six weeks to figure out what to do about Sumter.

President Buchanan made a few token efforts to resupply the fort, but otherwise followed his famous “stall until it’s Lincoln’s problem” strategy – pretty much his approach to everything between November 1860 and March 1861. Lincoln took office to discover he had less than six weeks to figure out what to do about Sumter.

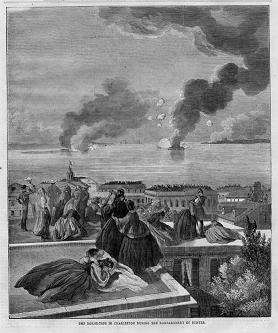

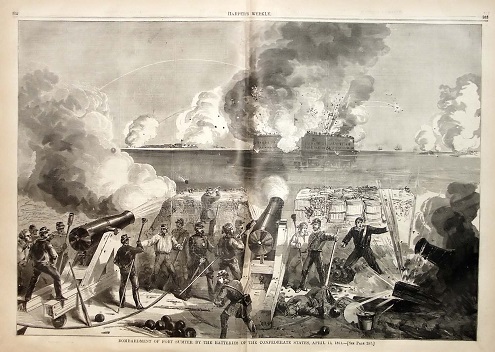

Cannons fired from multiple locations, flames and smoke and explosions – good times. Anderson eventually had remaining munitions dumped to prevent them igniting and blowing up the whole place from the inside. The tides carried the barrels back to the fort walls, where incoming fire ignited them – adding to the fireworks and the distinct impression perhaps Mrs. Chestnut’s friends were correct regarding God’s opinion of the matter.

Cannons fired from multiple locations, flames and smoke and explosions – good times. Anderson eventually had remaining munitions dumped to prevent them igniting and blowing up the whole place from the inside. The tides carried the barrels back to the fort walls, where incoming fire ignited them – adding to the fireworks and the distinct impression perhaps Mrs. Chestnut’s friends were correct regarding God’s opinion of the matter. Anderson surrendered around noon the next day. A cannon misfired during a final ceremonial salute to Old Gory and the resulting explosion killed two young soldiers.

Anderson surrendered around noon the next day. A cannon misfired during a final ceremonial salute to Old Gory and the resulting explosion killed two young soldiers.

One of the most bizarre mischaracterizations of history is the idea that in the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth, the Lord made the North free, and just, without prejudice or malice. He saw the North, and declared that it was ‘good’.

One of the most bizarre mischaracterizations of history is the idea that in the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth, the Lord made the North free, and just, without prejudice or malice. He saw the North, and declared that it was ‘good’. In reality, by the dawn of the 19th century there was slavery pretty much everywhere in the United States. More in some places than others, but it was a thing all over. There were abolitionists as well – pretty much everywhere – carrying on about the evil of the peculiar institution and making everyone unhappy.

In reality, by the dawn of the 19th century there was slavery pretty much everywhere in the United States. More in some places than others, but it was a thing all over. There were abolitionists as well – pretty much everywhere – carrying on about the evil of the peculiar institution and making everyone unhappy. Besides, they already had an entirely different class of not-quite-people to exploit and dehumanize. In the elite world of historiography, we call them the “Irish.”

Besides, they already had an entirely different class of not-quite-people to exploit and dehumanize. In the elite world of historiography, we call them the “Irish.” The cotton gin, as every middle school history teacher can tell you, made cotton production what we historians call ‘way cray’ more profitable – thus cementing slavery as an ‘essential’ institution for decades past its anticipated life span. Unintended consequences suck.

The cotton gin, as every middle school history teacher can tell you, made cotton production what we historians call ‘way cray’ more profitable – thus cementing slavery as an ‘essential’ institution for decades past its anticipated life span. Unintended consequences suck. Well, obviously the south is full of sinners. Not like us – we’re good people. That’s why we abolished it.

Well, obviously the south is full of sinners. Not like us – we’re good people. That’s why we abolished it. Wages [referring to ‘free’ factory labor in the North] is a cunning device of the devil, for the benefit of tender consciences who would retain all the advantages of the slave system without the expense, trouble, and odium of being slaveholders. (Orestes A. Brownson, 1840)

Wages [referring to ‘free’ factory labor in the North] is a cunning device of the devil, for the benefit of tender consciences who would retain all the advantages of the slave system without the expense, trouble, and odium of being slaveholders. (Orestes A. Brownson, 1840) The plot had more holes than Battlestar Galactica, and nearly as many characters we still can’t quite figure out whether to love or despise. (Say what you like about the Cylons, they at least had moral clarity.)

The plot had more holes than Battlestar Galactica, and nearly as many characters we still can’t quite figure out whether to love or despise. (Say what you like about the Cylons, they at least had moral clarity.)

The American Civil War is one of the most written about, discussed, reenacted, and debated events in all of human history. It was important, of course – major battles and nation-changing outcomes and all – but I’m not sure that’s its primary fascination for us.

The American Civil War is one of the most written about, discussed, reenacted, and debated events in all of human history. It was important, of course – major battles and nation-changing outcomes and all – but I’m not sure that’s its primary fascination for us. They’d declared independence together less than a century before and fought the British together – twice. Both extolled the same form of government (even after the South attempted to secede, the ‘nation’ they created for themselves was essentially the same in structure as the one they’d left). They quoted the same Declaration of Independence and revered the same Constitution.

They’d declared independence together less than a century before and fought the British together – twice. Both extolled the same form of government (even after the South attempted to secede, the ‘nation’ they created for themselves was essentially the same in structure as the one they’d left). They quoted the same Declaration of Independence and revered the same Constitution. In every region of the country, the dominant social, political, and economic class was composed almost entirely of straight white educated land-owning males. Most of them looked down on pretty much everyone else.

In every region of the country, the dominant social, political, and economic class was composed almost entirely of straight white educated land-owning males. Most of them looked down on pretty much everyone else.

It’s a mischaracterization, however, to imagine the North was mostly industrialized by 1860. The majority of Northerners lived and worked on small farms or in small businesses, growing food for themselves and their families and perhaps trading or selling surplus for other goods. Most factories were in the North, but most of the North wasn’t factories.

It’s a mischaracterization, however, to imagine the North was mostly industrialized by 1860. The majority of Northerners lived and worked on small farms or in small businesses, growing food for themselves and their families and perhaps trading or selling surplus for other goods. Most factories were in the North, but most of the North wasn’t factories. Southern geography meant agriculture on an entirely different scale. Long growing seasons, flatter lands, different soil – this was God’s way of promoting sugar, tobacco, and most of all, cotton. It was the Elvis of cash crops.

Southern geography meant agriculture on an entirely different scale. Long growing seasons, flatter lands, different soil – this was God’s way of promoting sugar, tobacco, and most of all, cotton. It was the Elvis of cash crops. This will be a problem for the South. That’s more foreshadowing – I hope I don’t ruin the ending for anyone.

This will be a problem for the South. That’s more foreshadowing – I hope I don’t ruin the ending for anyone. Not liking someone, not hiring them, or even not wanting to live next to them, didn’t mean you didn’t have to deal with them at all. The variety of cultures, languages, foods, beliefs, etc., forced a sort of tolerance and accommodation foreign to the South. At the same time, capitalist ideals and an early sort of ‘Social Darwinism’ largely prevented that accommodation from becoming too ‘kumbaya’.

Not liking someone, not hiring them, or even not wanting to live next to them, didn’t mean you didn’t have to deal with them at all. The variety of cultures, languages, foods, beliefs, etc., forced a sort of tolerance and accommodation foreign to the South. At the same time, capitalist ideals and an early sort of ‘Social Darwinism’ largely prevented that accommodation from becoming too ‘kumbaya’.