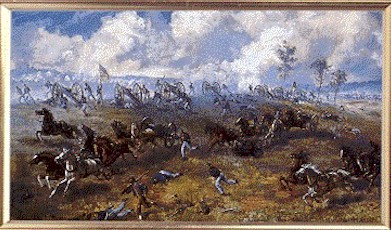

The Battle of Gettysburg was a three-day conflagration resulting from Robert E. Lee’s second and final attempt to bring the Civil War into the North, in hopes citizens therein would tire of the fighting and tell their elected leaders – Lincoln in particular – to knock it off.

The Battle of Gettysburg was a three-day conflagration resulting from Robert E. Lee’s second and final attempt to bring the Civil War into the North, in hopes citizens therein would tire of the fighting and tell their elected leaders – Lincoln in particular – to knock it off.

Those first three days of July, 1863, produced the sorts of epic moments and sickening body counts that made the war so grand and so terrible both then and in retrospect. You may have seen the movie, based on Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels – one of the few history movies shot entirely in real time.

That’s a joke about how damn long it is. It’s a really long movie.

Yep.

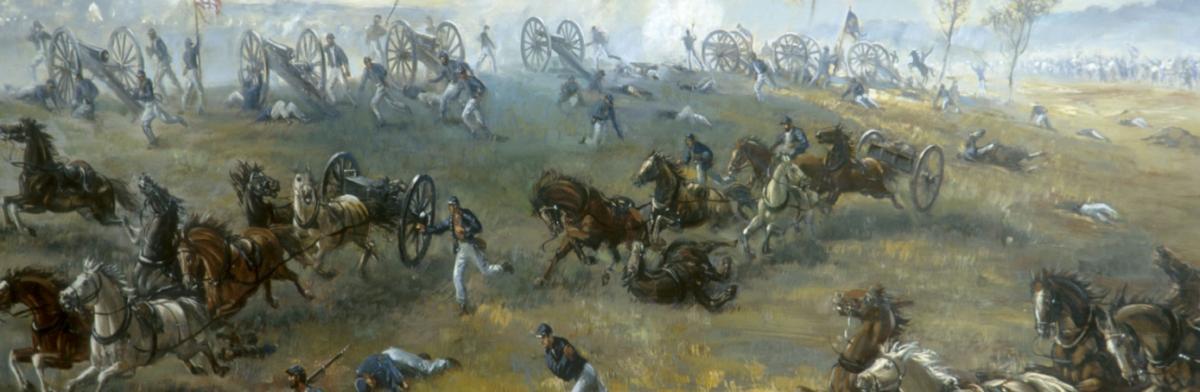

The battle was a critical turning point in the Eastern Theater of the war – a series of all-or-nothing melees culminating in the devastating “Pickett’s Charge,” in which the Confederates lost nearly half the men who charged proudly up Cemetery Ridge in hopes of overwhelming the entrenched Union forces awaiting them at the top.

The Union held, and the South was devastated beyond the point of possible recovery.

The same month saw the fall of Vicksburg in the Western Theater, the rapidly growing acceptance of black soldiers in the Union after Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick martyred themselves in the attack on Fort Wagner, and the pivotal Battle of Honey Springs in Indian Territory (the ‘Gettysburg of the West’, according to my state-approved Oklahoma History textbook).

The same month saw the fall of Vicksburg in the Western Theater, the rapidly growing acceptance of black soldiers in the Union after Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick martyred themselves in the attack on Fort Wagner, and the pivotal Battle of Honey Springs in Indian Territory (the ‘Gettysburg of the West’, according to my state-approved Oklahoma History textbook).

I’m serious about that last one only insofar as the book really does say that. But the other events were legit turning points. After Gettysburg and the rest of July 1863, the war was effectively decided.

That didn’t prevent it’s continuing for two more years, but that’s a subject for another post.

The small town of Gettysburg was left with 50,000+ dead soldiers to bury. The armies had done what they could, but the nature of war and the limited ground with which to work meant that it wasn’t long before local dogs or other animals were showing up in town with body parts as chew toys. Farmers trying to plow would run into limbs protruding from the earth. And once it rained…

It wasn’t decent, and it certainly wasn’t healthy.

It wasn’t decent, and it certainly wasn’t healthy.

Fast-forward to the christening of a massive cemetery, conceived and designed with a level of cooperation between state and national government which was not at all the norm of the times. The ceremony to dedicate the new grounds featured preachers praying prayers, choirs singing songs, and Edward Everett – the preeminent orator of his day.

Everett captivated the crowd with his three-hour speech summarizing the battle, the men, the cause, and whatever else you might ask for in the Director’s Cut of your favorite DVD. Contrary to what you were probably told as a kid, he was a hit – people loved that stuff back then because they had what was called “an attention span”, with a side of “absolutely nothing better to do all day.”

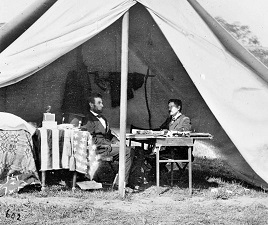

President Lincoln was invited as well, but unlike today the presence of the President did not automatically presume he would become central to everything else. Lincoln’s role was to give some closing comments before the final song or prayer – not to upstage Everett. While it’s likely people anticipated more than the two or three minutes it would have taken for him to deliver what became known as his “Gettysburg Address,” they certainly weren’t expecting anything particularly extensive either. That wasn’t why he was there.

President Lincoln was invited as well, but unlike today the presence of the President did not automatically presume he would become central to everything else. Lincoln’s role was to give some closing comments before the final song or prayer – not to upstage Everett. While it’s likely people anticipated more than the two or three minutes it would have taken for him to deliver what became known as his “Gettysburg Address,” they certainly weren’t expecting anything particularly extensive either. That wasn’t why he was there.

The suggestion that he scribbled the speech on the back of an envelope on the train ride in is counter to everything else we know about Lincoln and public speaking, and is refuted by specific history regarding this particular speech as well. (Like, we have the diary entries and such of men around him who recorded things like, “Lincoln asked my thoughts on his most recent edit of his speech. I suggested he wait for a dove to attack him on the train, but he insisted on borrowing my copy of ‘Greek Funeral Orations for Dummies’ and a thesaurus, so…” )*

The ‘holy inspiration’ myth speaks more to the power and seemingly supernatural impact of the speech in retrospect than it does anything based on temporal reality. Lincoln wrote how he wrote and spoke how he spoke as a result of years of study and practice, editing and peer review. He may have been inspired, but that inspiration was manifested as part of decades of hard work to get better at it.

The ‘holy inspiration’ myth speaks more to the power and seemingly supernatural impact of the speech in retrospect than it does anything based on temporal reality. Lincoln wrote how he wrote and spoke how he spoke as a result of years of study and practice, editing and peer review. He may have been inspired, but that inspiration was manifested as part of decades of hard work to get better at it.

So, there’s a lesson.

In case you don’t still have it memorized from Middle School, it went something like this:

Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation — or any nation so conceived and so dedicated — can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

It still gives me the goose shivers. Next time I’ll offer up my amateur breakdown of this classic historical ditty. I know you simply can’t wait.

*I’m paraphrasing

RELATED POST: The Gettysburg Address, Part Two (Dedicated to a Proposition)

RELATED POST: The Gettysburg Address, Part Three (Lincoln’s Big ‘But’)

RELATED POST: Useful Fictions, Part I – Historical Myths

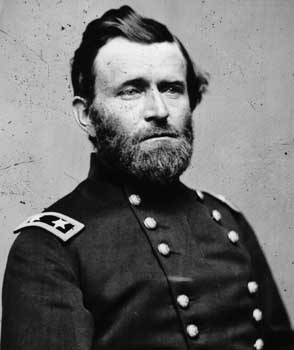

Grant was perhaps the single most bearded example of nothing working quite the way it should have during the American Civil War. He’d have never ended up a war hero, let alone future President, in a more ordered universe. I’m not sure he’d have existed at all.

Grant was perhaps the single most bearded example of nothing working quite the way it should have during the American Civil War. He’d have never ended up a war hero, let alone future President, in a more ordered universe. I’m not sure he’d have existed at all.

After several years of failed businesses and rocky times, opportunity struck when the Civil War erupted. He helped recruit and train volunteers in Illinois, but what he really wanted was a position in the “real” army. McClellan turned him down due to his reputation for drinking, which will prove ironic a few years later when Lincoln suggests someone find out WHAT Grant was drinking – and send it to the rest of his generals so they’d fight like he did.

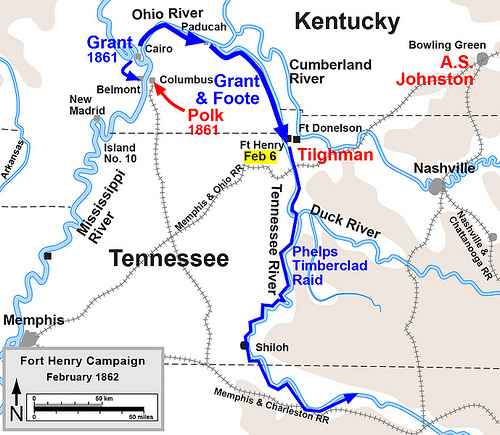

After several years of failed businesses and rocky times, opportunity struck when the Civil War erupted. He helped recruit and train volunteers in Illinois, but what he really wanted was a position in the “real” army. McClellan turned him down due to his reputation for drinking, which will prove ironic a few years later when Lincoln suggests someone find out WHAT Grant was drinking – and send it to the rest of his generals so they’d fight like he did.  He ended up leading a little campaign to take Ft. Henry along the Tennessee River, which connected to the Mississippi and ran near or through about 43 different states in play during the war. It became a fun little experiment in geography, strategy, and the pre-cell phone zaniness of coordinating land forces and ‘ironclads’ – experimental watercraft made of wood but clad in, well – iron.

He ended up leading a little campaign to take Ft. Henry along the Tennessee River, which connected to the Mississippi and ran near or through about 43 different states in play during the war. It became a fun little experiment in geography, strategy, and the pre-cell phone zaniness of coordinating land forces and ‘ironclads’ – experimental watercraft made of wood but clad in, well – iron.

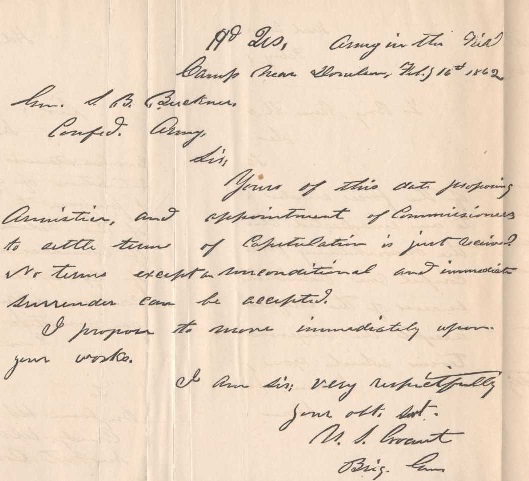

It’s at Ft. Donelson that U.S. Grant first makes the history books. After various military maneuvering of the sort some people seem to enjoy reading about in great detail, Grant had the Confederates in a world of hurt.

It’s at Ft. Donelson that U.S. Grant first makes the history books. After various military maneuvering of the sort some people seem to enjoy reading about in great detail, Grant had the Confederates in a world of hurt.

“I propose to move immediately upon your works” became a catchphrase throughout the North for almost any situation. Those of you who endured the decades of “Where’s the Beef?” or “Whatchu talking’ bout, Willis?” know how these things can go. Then again, this one grew organically – not as a result of marketing or even intent – so perhaps bringing up Different Strokes is a bit too harsh.

“I propose to move immediately upon your works” became a catchphrase throughout the North for almost any situation. Those of you who endured the decades of “Where’s the Beef?” or “Whatchu talking’ bout, Willis?” know how these things can go. Then again, this one grew organically – not as a result of marketing or even intent – so perhaps bringing up Different Strokes is a bit too harsh.

Your standard American History textbook will tell you that after First Bull Run, the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and began preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.

Your standard American History textbook will tell you that after First Bull Run, the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and began preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.  The vanity and honor culture of the South was pretty much unbearable long before First Bull Run, but their routing of the North after such build-up and so many supposed disadvantages reinforced the conviction of many Secesh that they simply could not, would not, should not lose – ever ever ever ever.

The vanity and honor culture of the South was pretty much unbearable long before First Bull Run, but their routing of the North after such build-up and so many supposed disadvantages reinforced the conviction of many Secesh that they simply could not, would not, should not lose – ever ever ever ever.

Here’s the problem with that kind of enemy: they don’t give up. I mean, I’m a big fan of all that ‘hold on tight to your dreams’ stuff, but there’s a time to make like Elsa and let it go.

Here’s the problem with that kind of enemy: they don’t give up. I mean, I’m a big fan of all that ‘hold on tight to your dreams’ stuff, but there’s a time to make like Elsa and let it go. Germany took a pretty severe beating before Hitler’s suicide opened the door to surrender, leaving Japan alone in the fight – but they couldn’t let themselves accept the inevitable. WE DROPPED AN ATOMIC BOMB ON THEM, and they were still, like “I dunno – seems to me we can still make this work.”

Germany took a pretty severe beating before Hitler’s suicide opened the door to surrender, leaving Japan alone in the fight – but they couldn’t let themselves accept the inevitable. WE DROPPED AN ATOMIC BOMB ON THEM, and they were still, like “I dunno – seems to me we can still make this work.” If Bull Run left the South feeling confirmed in their invulnerability, it left the North soiling their armor at rabbits. Yes, the President and co. dug in for a real war, but the psychological impact of blowing a ‘sure thing’ – so much so that they skulked back to Washington in terror and shame – didn’t fade quickly. Add to this the grand delusions of General George B. McClellan, who led Union troops through much of the first part of the war – and we have a problem.

If Bull Run left the South feeling confirmed in their invulnerability, it left the North soiling their armor at rabbits. Yes, the President and co. dug in for a real war, but the psychological impact of blowing a ‘sure thing’ – so much so that they skulked back to Washington in terror and shame – didn’t fade quickly. Add to this the grand delusions of General George B. McClellan, who led Union troops through much of the first part of the war – and we have a problem.  You’d think this would mean less bloodshed, but in reality it protracted the conflict unnecessarily for months – maybe years. It drove Lincoln crazy, despite his calm veneer – at one point he wrote to McClellan asking if perhaps he could borrow the army for a time, seeing as how he wasn’t using it for anything.

You’d think this would mean less bloodshed, but in reality it protracted the conflict unnecessarily for months – maybe years. It drove Lincoln crazy, despite his calm veneer – at one point he wrote to McClellan asking if perhaps he could borrow the army for a time, seeing as how he wasn’t using it for anything.

Through the smoke and haze of battle, the boys who would later be in blue could tell fresh troops were falling into place across the way. Those looking behind for their own reinforcements were… disappointed.

Through the smoke and haze of battle, the boys who would later be in blue could tell fresh troops were falling into place across the way. Those looking behind for their own reinforcements were… disappointed.  OK, he was already weird before the battle. A brilliant strategist, Jackson was nonetheless an unlikely leader of men. He was socially awkward, and his classes at Virginia Military Institute were notorious for their tedium.

OK, he was already weird before the battle. A brilliant strategist, Jackson was nonetheless an unlikely leader of men. He was socially awkward, and his classes at Virginia Military Institute were notorious for their tedium. It was THIS figure who confronted the men who’d begun to fall back in the face of superior firepower. Jackson didn’t yell, so his voice would have been raised only in order to be heard above the din. He told them to form a line and hold it.

It was THIS figure who confronted the men who’d begun to fall back in the face of superior firepower. Jackson didn’t yell, so his voice would have been raised only in order to be heard above the din. He told them to form a line and hold it. General Bee, who was not particularly weird OR inspiring, saw this from across the way and recognized its power. Knowing he couldn’t pull it off personally, he instead pointed it out to his men: “Look! There’s Jackson, standing like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”

General Bee, who was not particularly weird OR inspiring, saw this from across the way and recognized its power. Knowing he couldn’t pull it off personally, he instead pointed it out to his men: “Look! There’s Jackson, standing like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”  First Bull Run was the first time Union troops would experience one of the more bone-chilling elements of the Civil War. This was possibly Jackson’s doing as well. (Hey, once you’ve got a cool nickname, anything is possible.)

First Bull Run was the first time Union troops would experience one of the more bone-chilling elements of the Civil War. This was possibly Jackson’s doing as well. (Hey, once you’ve got a cool nickname, anything is possible.)

And yet, things remained relatively calm. Disorderly, to be sure – frustrating, and volatile. But there was no panic – at first.

And yet, things remained relatively calm. Disorderly, to be sure – frustrating, and volatile. But there was no panic – at first.  Your standard American History textbook will tell you the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and begin preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.

Your standard American History textbook will tell you the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and begin preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.

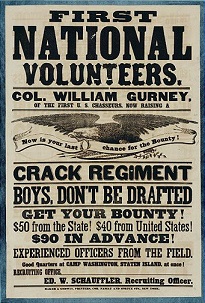

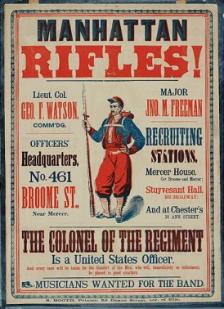

After Sumter, the Union called for soldiers from the loyal states, some of whom actually sent them. Generals were often elected by their men or appointed for their political connections, so knowing what you were doing wasn’t really top priority at this stage. Men signed up eagerly for the good times to come – war was a mostly theoretical adventure, and defeating the silly South would be good times.

After Sumter, the Union called for soldiers from the loyal states, some of whom actually sent them. Generals were often elected by their men or appointed for their political connections, so knowing what you were doing wasn’t really top priority at this stage. Men signed up eagerly for the good times to come – war was a mostly theoretical adventure, and defeating the silly South would be good times.  President Lincoln appointed Irvin McDowell to make this happen, but McDowell was skeptical about the supposed ease of such a mission. He’d done real war before, and was concerned about trying to send men into battle based on the harassment of impatient politicians and newspapers. He was famously reassured by President Lincoln, “You are green, it is true, but they are green also; you are all green alike.”

President Lincoln appointed Irvin McDowell to make this happen, but McDowell was skeptical about the supposed ease of such a mission. He’d done real war before, and was concerned about trying to send men into battle based on the harassment of impatient politicians and newspapers. He was famously reassured by President Lincoln, “You are green, it is true, but they are green also; you are all green alike.”

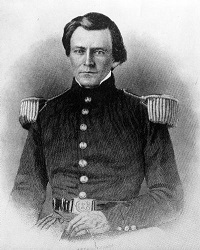

Unfortunately P.G.T. Beauregard, our friend from the attack on Ft. Sumter, was waiting for him just outside of Richmond. He had a plan as well, once the Yankee oppressors arrived – fake to the right, attack hard on the left, flank the enemy. Once between the army and the capital, they’d have no choice but to surrender. War over – here comes the honor and the glory (and let’s use some discretion regarding the ladies).

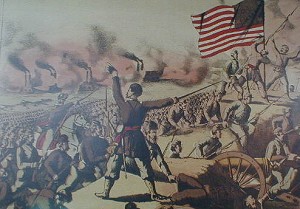

Unfortunately P.G.T. Beauregard, our friend from the attack on Ft. Sumter, was waiting for him just outside of Richmond. He had a plan as well, once the Yankee oppressors arrived – fake to the right, attack hard on the left, flank the enemy. Once between the army and the capital, they’d have no choice but to surrender. War over – here comes the honor and the glory (and let’s use some discretion regarding the ladies).  People were getting SHOT! IN THE BODY! Cannonballs were tearing off limbs, and bullets were splattering the brains of friends. Many bowels and bladders were emptied in those opening hours, and shame quickly gave way to survival instinct for some as this glorious adventure turned out to suck majorly. This was NOT GLORIOUS AND WHAT THE HELL THEY’RE TRYING TO KILL US ALL!

People were getting SHOT! IN THE BODY! Cannonballs were tearing off limbs, and bullets were splattering the brains of friends. Many bowels and bladders were emptied in those opening hours, and shame quickly gave way to survival instinct for some as this glorious adventure turned out to suck majorly. This was NOT GLORIOUS AND WHAT THE HELL THEY’RE TRYING TO KILL US ALL!