These are complicated times, and in the interest of serving ALL students (and avoiding as many problems with parents as possible), I’m renewing my commitment to avoid pushing my own personal values and ideology and just sticking to the facts.

These are complicated times, and in the interest of serving ALL students (and avoiding as many problems with parents as possible), I’m renewing my commitment to avoid pushing my own personal values and ideology and just sticking to the facts.

It’s not that hard in early American history. I mean, sure – there’s the issue of Columbus and whether he “discovered” America or not. Rather than give my own opinions, I just give kids facts. I’ve prepared a sheet of links to over 200 scholarly sources and primary documentation for them to peruse at their leisure, and they can decide for themselves whether or not what Columbus did was “good” or “bad,” or whether the Vikings got here first, or the Chinese, or that guy from Africa whose name I can never remember.

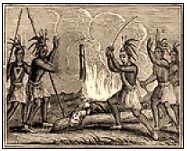

The whole clash of early settlers and the natives can be a little tricky, but no worries – I just present all sides of the issues and let my 8th and 9th graders figure out what it all means. It’s not my job to label something as “genocide” or “natural progress” or “God’s will.” Maybe smallpox blankets were a tacky move, maybe not. Maybe scalping and raping and burning down homes and bashing out babies’ brains was savage, maybe not. There were good people on both sides.

I’ve compiled some sketches from the impacted tribes along with a few scraps of sympathetic white accounts, some primary sources from European colonists, and deleted scenes from the Director’s Cut of Pocahontas. (I realize some would argue the Disney movie isn’t an accurate portrayal of history, but as I’ve already explained, I’m trying not to take sides.)

Young people are naturally interested in the Salem Witchcraft Trials. It’s a topic that’s become so sensationalized in our culture that it’s used as an analogy for everything from the anti-Communist hysteria of the mid-20th century to any effort to hold elected leaders accountable for poor behavior. You think I’m wading into THAT minefield when we cover it in class? No way!

Young people are naturally interested in the Salem Witchcraft Trials. It’s a topic that’s become so sensationalized in our culture that it’s used as an analogy for everything from the anti-Communist hysteria of the mid-20th century to any effort to hold elected leaders accountable for poor behavior. You think I’m wading into THAT minefield when we cover it in class? No way!

Instead, I’ve got the trial transcripts in the King James English, some commentary from Cotton Mather, and Samuel Sewell’s apology years after. Were the condemned actually witches? Not my call to make! Should we burn people at the stake for acting strange or based on the testimony of teenagers faking seizures? Maybe. Maybe not. I’m suggesting students read the transcripts and consult the dozens of scholarly analyses available to decide what really happened on their own. I’m trying not to take sides.

The American Revolution! Independence! Freedom! Yeah, also not going there. We’ll cover the documents and discuss some of the main events happening around that time, but I’m not sure it’s a good idea for me inflict my own perception of what “caused” the Revolution, let alone whether or not the rebels made the right call. Better I just share some random facts for them to connect (or not) on their own and leave my personal patriotism out of it.

Maybe America was something new and special, maybe it wasn’t. Maybe the Declaration of Independence is the finest document ever written, maybe it’s not. Maybe the Bill of Rights turned out to be a pretty good idea, and maybe it’s all crap we can ignore when inconvenient. I love those documents, those ideals, and even how beautifully they were phrased – but… I’m paid by tax dollars. Not here to brainwash. Stick to the facts.

So I’m not pushing my patriotism on kids any more than I’d try to convert them to my faith or expect them to conform to my own narrow ideas about civility and human decency. It’s not my place to tell them what to believe, just to provide un-curated information related to state standards and stand back. They may then peruse mankind’s collected writings at their convenience and decide for themselves whether or not representation should or should not be considered a prerequisite for taxation. I’m trying not to take sides.

So I’m not pushing my patriotism on kids any more than I’d try to convert them to my faith or expect them to conform to my own narrow ideas about civility and human decency. It’s not my place to tell them what to believe, just to provide un-curated information related to state standards and stand back. They may then peruse mankind’s collected writings at their convenience and decide for themselves whether or not representation should or should not be considered a prerequisite for taxation. I’m trying not to take sides.

Indian Removal, slavery, the Age of Jackson, the Civil War, Westward Expansion, War with Mexico, Imperialism – I refuse to get sucked in to ethical, philosophical, or religious discussions about “right” and “wrong.” It’s not my place to refute the idea that the moon landing was faked, that the earth is flat, or that immunizations cause autism.

It’s entirely possible science isn’t even a thing that happens. Perhaps it’s a massive worldwide conspiracy run by antifa agents and Bill Gates to support their child sex slavery pizza parlors and brainwash our children into becoming gay Muslims. Personally, I suspect science is a real thing but gets stuff wrong sometimes and not all scientists are as objective as we’d like. But I’m not committing either way on any of these hot-button issues. That’s not my place. I’m trying not to take sides.

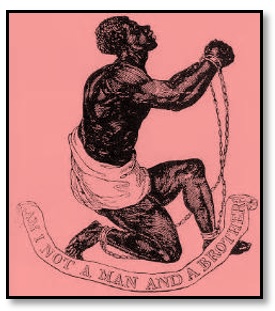

I remember a young man asking me last year whether or not it was true that Africans had evolved in such a way as to be “well-suited” for slavery – that they had the “mark of Cain” and God had set them aside to serve whites and play basketball and that’s why they were so good at both. I was personally horrified, of course, but race is a loaded issue and, as I’ve been reminded repeatedly over the years, it’s not my place to inject my personal opinions in class. For a moment, I wasn’t sure how I’d be able to maintain my professional distancing as I’ve been so often berated to do.

I asked him to give me a day to consider what he’d asked. That evening, I compiled the writings of Frederick Douglass, James Baldwin, and nearly a hundred other black intellectuals in American history, along with the speeches of famous southerners, Klan leaders, and transcripts from several Mel Gibson films. I also provided links to some of the more violent white supremacy websites along with a suggestion he Google #BlackLivesMatter. If he really cares about the issue, he can spend the next several decades pouring over the studies, experiences, opinions, and diatribes of those on all sides of the issue. It’s really not my place to take a position on the “humanity” or “equality” of this group or that – especially when it might offend certain stakeholders in the community.

I asked him to give me a day to consider what he’d asked. That evening, I compiled the writings of Frederick Douglass, James Baldwin, and nearly a hundred other black intellectuals in American history, along with the speeches of famous southerners, Klan leaders, and transcripts from several Mel Gibson films. I also provided links to some of the more violent white supremacy websites along with a suggestion he Google #BlackLivesMatter. If he really cares about the issue, he can spend the next several decades pouring over the studies, experiences, opinions, and diatribes of those on all sides of the issue. It’s really not my place to take a position on the “humanity” or “equality” of this group or that – especially when it might offend certain stakeholders in the community.

Students complain that other history teachers “tell them stories” about events in history or talk about famous historical figures. I’m like, woah! Spoon-fed, much? Telling stories is just a euphemism for “putting your own spin” on historical events, not to mention it requires deciding which events are important enough to discuss in the first place. That sounds like a job for your pastor, parents, or local politicians to decide.

Talking about “famous” figures is even worse. Some people consider Thomas Jefferson a Founding Father and an icon of American History. Others believe he’s a monster for his relationship with Sally Hemmings (one of his slaves). One side treasures his words and ideals, the other condemns his hypocrisy. You think I’m going to so much as MENTION him when literal blood is being spilt over whether or not to tear down his statue? The last thing we want to do is connect anything in the news with something from history – the mere suggestion that we can potentially shed light on current events by considering comparable events in our past can quickly become both a very unpleasant local news story and a fireable offense. This is “history” class, kids – not “people alive today” class. Look it up.

Seriously. Look it up. Alone on your own time and without any guidance. It’s not my job to help you sift through the overwhelming volume of noise and nonsense out there and decide which parts form a common national narrative. I’m just here to teach you the facts. You’re 15 – work out the rest on your own.

Was John Brown right to decapitate those settlers in front of their wives and kids? Not my call. Should women have the right to vote? Hard to say – there are good arguments on both sides. How well did Communism actually work out in the Soviet Union? Gosh, I dunno… there are all sorts of reasons they may have decided to move away from the “U.S.S.R.” thing and tear down that wall. Who am I to say? Did “executive privilege” place President Nixon above the law? Maybe – have to ask your parents about that one, not really an appropriate question for American Government class.

Was John Brown right to decapitate those settlers in front of their wives and kids? Not my call. Should women have the right to vote? Hard to say – there are good arguments on both sides. How well did Communism actually work out in the Soviet Union? Gosh, I dunno… there are all sorts of reasons they may have decided to move away from the “U.S.S.R.” thing and tear down that wall. Who am I to say? Did “executive privilege” place President Nixon above the law? Maybe – have to ask your parents about that one, not really an appropriate question for American Government class.

Was it necessary to execute all those Jews to save Germany? Maybe – I mean, I have some opinions on the subject along with research by experts who’ve spent lifetimes studying such things and exploring how such evils occur and why we don’t do more to speak out against them. But, I mean… there was a reason they threw the intellectuals in there with the homosexuals and the Gypsies, so maybe it’s best I avoid taking sides.

As it turns out, even my last recourse of “facts only” education presents a political and social dilemma. Honestly, I thought tossing my kids unguided into a forest filled with yellow ribbons was about as fair and balanced as any educated person could be expected to attempt. My narrow-minded ideology, however, that some things in history are supported by “evidence” while others simply aren’t (even while acknowledging that many topics fall somewhere in between) is apparently just as hurtful as when I suggested that websites ending in .edu or .gov might be slightly more reliable than Bubba’sConfederateBasement.com with all of its misspellings and that bright red twinkling background with the synthesized version of “Dixie” playing far too loudly.

I’ll do better. From now on, we won’t just cover facts. We’ll give equal time and merit to anything anyone anywhere has ever made up, tweeted, posted on Facebook, ranted about at a family dinner, or wormed their way onto TV (or YouTube) to talk about. Out of “respect for the office,” we’ll prioritize the bizarre ramblings of anyone paid by our tax dollars, no matter how bizarre or destructive the content of their remarks.

It will be difficult, at first, fighting the urge to distinguish between propaganda, science, documented reality, cultish beliefs, and anything else that comes flying our way, but I’m sure I’ll get used to it along with everything else. Besides, I’m trying not to take sides.

1. The tribes of the Great Plains faced confinement or extermination as the 19th century drew to a close; they were desperate and confused in the face of ongoing U.S. expansion, aggression, and manipulation.

1. The tribes of the Great Plains faced confinement or extermination as the 19th century drew to a close; they were desperate and confused in the face of ongoing U.S. expansion, aggression, and manipulation. The Second Ghost Dance: Wovoka

The Second Ghost Dance: Wovoka As tends to happen with ideas as they spread, Wovoka’s message quickly evolved as it was taken up by different tribes. With the Lakota Sioux in particular, it took on a more militant tone. Their concept of renewal – of heaven on earth – was incompatible with the presence of white folks, despite Wovoka’s calls for racial unity. It was also most likely a Lakota who added the idea of a “ghost shirt,” which would render its wearer impervious to bullets (since, presumably, you can’t shoot ghosts). It was exposure to the Sioux version of Wovoka’s visions which most led to white characterizations of the dance at the heart of the movement as a “Ghost Dance” with militant overtones.

As tends to happen with ideas as they spread, Wovoka’s message quickly evolved as it was taken up by different tribes. With the Lakota Sioux in particular, it took on a more militant tone. Their concept of renewal – of heaven on earth – was incompatible with the presence of white folks, despite Wovoka’s calls for racial unity. It was also most likely a Lakota who added the idea of a “ghost shirt,” which would render its wearer impervious to bullets (since, presumably, you can’t shoot ghosts). It was exposure to the Sioux version of Wovoka’s visions which most led to white characterizations of the dance at the heart of the movement as a “Ghost Dance” with militant overtones.  Big Foot had led his group to the Pine Ridge Reservation to surrender. They were told to set up camp while officials figured out what to do with them next. The next day, December 29th, 1890, soldiers were sent into the camp to gather any remaining weapons among the Sioux. It’s unclear to what extent the Lakota resisted. Some accounts refer to a medicine man encouraging them to don their “ghost shirts” and fight, while others focus on a single young Sioux, probably deaf, who attempted to retain his rifle. Whatever the specifics, at some point a shot was fired and things pretty much went to hell from there.

Big Foot had led his group to the Pine Ridge Reservation to surrender. They were told to set up camp while officials figured out what to do with them next. The next day, December 29th, 1890, soldiers were sent into the camp to gather any remaining weapons among the Sioux. It’s unclear to what extent the Lakota resisted. Some accounts refer to a medicine man encouraging them to don their “ghost shirts” and fight, while others focus on a single young Sioux, probably deaf, who attempted to retain his rifle. Whatever the specifics, at some point a shot was fired and things pretty much went to hell from there.

Most of us have at least a working familiarity with the story of Joan of Arc. A simple (but not impoverished) French peasant girl, she began hearing voices from God telling her she was going to save France from the English and their Burgundian allies. Through some combination of cleverness, sincerity, and miraculous signs, she convinced Charles VII to let her lead French soldiers in battle and eventually secured his coronation.

Most of us have at least a working familiarity with the story of Joan of Arc. A simple (but not impoverished) French peasant girl, she began hearing voices from God telling her she was going to save France from the English and their Burgundian allies. Through some combination of cleverness, sincerity, and miraculous signs, she convinced Charles VII to let her lead French soldiers in battle and eventually secured his coronation. Even in a charade of a trial, participants generally strive to persuade themselves before seeking to persuade others. Humans are corrupt and selfish, to be sure – but most of us still want to be able to sleep at night. We like to win, but we don’t like to feel like horrible people while doing it. We demand a narrative – however twisted or internal – which justifies our treatment of others. We want to feel right.

Even in a charade of a trial, participants generally strive to persuade themselves before seeking to persuade others. Humans are corrupt and selfish, to be sure – but most of us still want to be able to sleep at night. We like to win, but we don’t like to feel like horrible people while doing it. We demand a narrative – however twisted or internal – which justifies our treatment of others. We want to feel right.  Thus, in the end, there were really only two points on which Cauchon and his cohorts found traction, even by their own standards.

Thus, in the end, there were really only two points on which Cauchon and his cohorts found traction, even by their own standards. Trial transcripts record repeated questioning of Joan concerning her attire. She expressed complete willingness to change into a dress once moved to a church prison, where she’d be guarded by women, as church law required. Her request was, each time, denied. Joan was asked to recite the Lord’s Prayer (something a witch would be unable to do). Again she was compliant, if only she were first given the opportunity for a proper confession. Impossible, unless she changed her outfit! And the cycle began anew.

Trial transcripts record repeated questioning of Joan concerning her attire. She expressed complete willingness to change into a dress once moved to a church prison, where she’d be guarded by women, as church law required. Her request was, each time, denied. Joan was asked to recite the Lord’s Prayer (something a witch would be unable to do). Again she was compliant, if only she were first given the opportunity for a proper confession. Impossible, unless she changed her outfit! And the cycle began anew. 1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery.

1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery. Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.

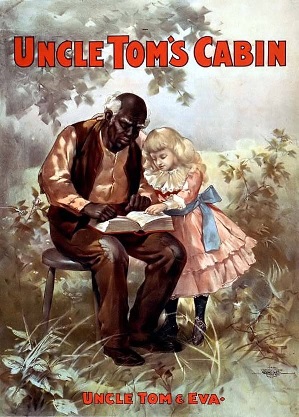

Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.  Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.)

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.) John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…”

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…” From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address:

From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address: 1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.