I have not told half of what I saw. (Marco Polo on his death bed, when encouraged to retract some of his crazy stories before facing judgement)

It’s unlikely that Polo actually observed firsthand everything he claimed… (Every Polo biographer since then)

I’ve been watching Marco Polo on Netflix. The series didn’t last long – it started strong, then tanked after two short seasons. Apparently Netflix took quite a loss.

I’ve been watching Marco Polo on Netflix. The series didn’t last long – it started strong, then tanked after two short seasons. Apparently Netflix took quite a loss.

It’s interested me enough so far, though, that I started a book about Polo and his travels. I picked it up used a few months ago for my classroom library, then forgot about it until packing up for the summer. Since I’m watching the series, I figured I’d bring it home.

Marco Polo is an interesting tale on several levels, not least because it’s not always easy to tell when he’s reporting hard facts (however unbelievable they must have seemed to readers), when he’s employing hyperbole or artistic license to make a larger point, or when he’s repeating legends and hearsay as firsthand experience. Further complicating matters, his account was written many years after the events it describes, and with the help of a successful romance novelist. So… take his story for what it is.

Except… I’m not actually reading Marco Polo’s account of his travels – I’m reading ABOUT Marco Polo and his account. While I don’t doubt the expertise of the author, I’m learning the parts SHE finds most significant or interesting, through HER voice and interpretation of HIS voice and interpretation. Modern commentary, facts, and expert insight into a seven hundred-year-old travelogue shamelessly mixing commentary, facts, and hearsay.

And wild lesbian orgies.

Or are those just in the Netflix version? I’m still learning as I go on this one.

Which brings me back to history according to Netflix. The series is an artistic spin on Polo’s account, itself an artistic spin, both based-on-but-not-bound-by factual history. I’m hardly an expert on the subjects involved, so I’ve developed a system for determining historical validity.

If a passage in the book connects with something in the show, and they more or less agree, I consider that information irrefutable. If I watch the series struggle through something counterintuitive in terms of accessible storylines, I internally file that information as plausible. And anything including extended lesbian orgies, I accept as artistic discretion – essential to a larger truth, whether they fit the story or not.

And oh, what artistic discretion! Here, I’ll rewind and show you again as proof…

I fear perhaps I’m modeling some rather shoddy history. It seems like I should be far more concerned with accuracy and documented facts as best they can be discerned. I used to cringe at Disney’s Pocahontas, and I still resent The Patriot and Cold Mountain. Why go soft now?

Still, the show DID get me reading the book. And much of the information I’d have otherwise had difficulty synthesizing or retaining has proven “stickier” because I enjoy the show. Events or characters which wouldn’t necessarily rouse my intellectual ya-yas on the printed page give me a bit of a rush when I recognize them from the screen. When I recently predicted the behavior of a character based on my reading, you’d have thought I’d just translated the lost languages of Mohenjo-Daro or unearthed a pristine copy of the Trump pee-tape. The circle was now complete! I was but the learner. Now, I am the Master! Step aside, David McCullough – I GOT THIS.

I had a professor at Tulsa Junior College back in the day who taught several of the required history classes most four-year universities expected as part of a well-rounded transfer student. I remember two big things about those classes.

The first was Hannibal – the only Black kid in the room. Hannibal knew a great deal more than I did about American (or any other) history. He and I had several interesting conversations about being Black in a socially “white” world, especially in the context of public schooling. Whatever clue-age I managed in my early years of teaching students who weren’t entirely like me was largely due to his patience and clarity. I wish I could thank him.

The other part I remember was the impact of Professor Burke’s stories about American history. I was particularly entranced by my first exposure to the tawdry tales of Andrew Jackson and Rachel Donelson.

Donelson was a divorced woman at a time when aspiring public figures did not associate with – let alone marry – such soiled creatures. Jackson fell in love with her and they wed, only to discover a few years later that her original divorce had never been finalized and they’d been living in bigamy. Jackson fought for her honor – sometimes literally – but his political opponents fed on the fallout and it was simply too scandalous to fully overcome.

Donelson was a divorced woman at a time when aspiring public figures did not associate with – let alone marry – such soiled creatures. Jackson fell in love with her and they wed, only to discover a few years later that her original divorce had never been finalized and they’d been living in bigamy. Jackson fought for her honor – sometimes literally – but his political opponents fed on the fallout and it was simply too scandalous to fully overcome.

After losing the controversial Election of 1824, Jackson finally won the Presidency in 1828, a watershed moment in the expansion of American democracy and for all practical purposes the birth of the modern Democratic Party. Rachel died before Inauguration Day of heart failure; Jackson forever blamed his political opponents.

Professor Burke’s tales of Jackson and Rachel and her ex-husband – an abusive scoundrel named Lewis Robards – were the sort of baroque melodrama cable TV and YA fiction later learned to weave into dirty gold. The stories were full of anachronisms and hyperbole and plot condensations – reduced like soup to their tastiest elements. I wasn’t the sharpest kid in the room, but even back then I was pretty sure Rachel hadn’t telephoned Jackson in distress (“Andy! Andy! He’s fulminating at me again!), nor had “Andy” hopped onto his duel-sport to Lancelot her away to the Hermitage.

But I didn’t care – I loved his stories and felt like I was learning. Years later, Professor Burke’s stories repeatedly anchored the “real” learning I did about Jackson and his world – kinda like this silly Marco Polo show.

Other times, though, the ways in which history is presented, distorted, or simply fabricated, aren’t intended to enlighten, educate, or even entertain. Sometimes people just LIE – to manipulate, to justify, to obfuscate. In recent years, I’m not even sure many of the worst perpetrators actually KNOW what’s supportable and what’s not in their bizarre renderings; they don’t even seem to care. Simply repeat the lie ad infinitum, and make its refutation personal – as if history is just another religious doctrine or political ideology to be hurled at one’s enemies or slathered like cheap gilding over your own corrupted ideologies.

Other times, though, the ways in which history is presented, distorted, or simply fabricated, aren’t intended to enlighten, educate, or even entertain. Sometimes people just LIE – to manipulate, to justify, to obfuscate. In recent years, I’m not even sure many of the worst perpetrators actually KNOW what’s supportable and what’s not in their bizarre renderings; they don’t even seem to care. Simply repeat the lie ad infinitum, and make its refutation personal – as if history is just another religious doctrine or political ideology to be hurled at one’s enemies or slathered like cheap gilding over your own corrupted ideologies.

Not to be too dramatic or anything. I mean, I’m not Marco Polo.

Reality matters. Oddly, this is a controversial and politically loaded statement at the moment. Facts are important, even when they’re inconvenient – sometimes BECAUSE they’re inconvenient. They don’t change based on the sheer repetition of bombastic nonsense or the lusts and machinations of the powerful.

But compiled facts aren’t usually SUFFICIENT if we’re trying to learn cohesive lessons. They can’t teach us what matters, or explain causes, effects, motivations, failures, or human nature. All history is interpretive – no matter who’s telling it or who pretends it could or should be otherwise. Events happen for reasons, they have effects, they fit into various contexts and complicate multiple lives. There’s also simply too damn many of them to present the entire record of mankind as an unbroken, sterilized anthology. And we keep learning about and creating more of all of it – daily.

How to best pick and choose, present and shape that history is a valid question and an appropriate debate. It assumes, however, that those so engaged are operating within an agreed upon range of morally defensible goals. Choosing a Black guy to play James Madison who breaks into song while engaging an Asian Aaron Burr is artistic discretion; insisting that the Civil War was about states’ rights or that most slaves were slaves by choice are damnable lies which do real damage to living people and our collective memory, no to mention our collective ideals.

Netflix, presumably, wants to make a few bucks pushing popular history. Polo likely wanted to thrill his audiences while still introducing them to an exotic world he found genuinely amazing. Professor Burke just wanted to help a bunch of clueless kids learn and remember some American History. I’ve shaped a few tales myself over the years, attempting to emphasize a lesson or better understand an era. Sometimes it works, other times I’m just… wrong.

None of which deserve the sort of condemnation earned by intentional twisting or recklessly disregarding our collective past in the service of narcissism, power, marginalization, “other-izing,” or the deification of evil.

History teaches us. It challenges us. It entertains us. Sometimes it confuses or discourages us; other times it exhorts and enlightens us. It’s bigger than our understanding and better than our application.

History may be complicated and subject to some interpretation. It may provide inspiration for some questionable artistic spins in the name of entertainment or experimentation. What it should NEVER be, however – what it MUST NOT become – is the subjective plaything of whoever’s in charge, to manipulate and discard as they whim.

Compared to that, how much harm can a few more lesbian orgies really do?

Now where’s that remote…?

RELATED POST: Useful Fictions, Part I – Historical Myths

RELATED POST: Useful Fictions, Part III – Historical Fiction… Sort Of

RELATED POST: Useful Fictions, Part V – “Historical Fiction,” Proper

Gottwald was flanked by his comrades, with Clementis standing close to him. It was snowing and cold, and Gottwald was bareheaded. Bursting with solicitude, Clementis took off his fur hat and set it on Gottwald’s head.

Gottwald was flanked by his comrades, with Clementis standing close to him. It was snowing and cold, and Gottwald was bareheaded. Bursting with solicitude, Clementis took off his fur hat and set it on Gottwald’s head. Four years later, Clementis was charged with treason and hanged. The propaganda section immediately made him vanish from history and, of course, from all photographs. Ever since, Gottwald has been alone on the balcony. Where Clementis stood, there is only the bare palace wall. Nothing remains of Clementis but the fur hat on Gottwald’s head.

Four years later, Clementis was charged with treason and hanged. The propaganda section immediately made him vanish from history and, of course, from all photographs. Ever since, Gottwald has been alone on the balcony. Where Clementis stood, there is only the bare palace wall. Nothing remains of Clementis but the fur hat on Gottwald’s head.

The story of Joan of Arc forces historians to deal with overtly spiritual claims and potentially miraculous outcomes in ways historians do not generally wish to do. We’ll cover the role of religion in the most general ways, if absolutely necessary, but we DON’T LIKE TO TALK ABOUT IT IF WE DON’T HAVE TO.

The story of Joan of Arc forces historians to deal with overtly spiritual claims and potentially miraculous outcomes in ways historians do not generally wish to do. We’ll cover the role of religion in the most general ways, if absolutely necessary, but we DON’T LIKE TO TALK ABOUT IT IF WE DON’T HAVE TO.  Immutable internal organs or not, how can you tell Joan’s story without pondering her faith? Her voices? She was either crazy with a healthy side of lucky, a very effective liar, or God spoke to her and sent her on a miracle-laden mission to save France from the English. The idea God could like France is problematic enough – but successful wars based on divine visions? Is that something we wish to encourage?

Immutable internal organs or not, how can you tell Joan’s story without pondering her faith? Her voices? She was either crazy with a healthy side of lucky, a very effective liar, or God spoke to her and sent her on a miracle-laden mission to save France from the English. The idea God could like France is problematic enough – but successful wars based on divine visions? Is that something we wish to encourage? If we’re going to acknowledge the hypocrisy and cruelty done in the name of God by early Spanish explorers confronting local Amerindians, let’s recognize the good intentions and legitimate faith of many others in similar situations. If we’re going to explain the cultural destruction done by Anglo-American missionaries to the tribes in their purview, let’s be a bit more vocal about the role of faith driving Samuel Worcester and his nameless ilk who served among the Natives with little reward in this life.

If we’re going to acknowledge the hypocrisy and cruelty done in the name of God by early Spanish explorers confronting local Amerindians, let’s recognize the good intentions and legitimate faith of many others in similar situations. If we’re going to explain the cultural destruction done by Anglo-American missionaries to the tribes in their purview, let’s be a bit more vocal about the role of faith driving Samuel Worcester and his nameless ilk who served among the Natives with little reward in this life.  As we approach modern times, it makes for a rather lopsided view of Presidential paradigms when we discuss foreign policy through every lens but the one most-cited from the Big Podium. “For we must consider that we shall be as a City Upon a Hill…” said John Winthrop in 1630 – a sentiment echoed, reworked, expanded, and cited over and over and over and over by men deciding whether or not we put our best in harm’s way in hopes of spreading that light a little further, or at least holding back the darkness a little longer.

As we approach modern times, it makes for a rather lopsided view of Presidential paradigms when we discuss foreign policy through every lens but the one most-cited from the Big Podium. “For we must consider that we shall be as a City Upon a Hill…” said John Winthrop in 1630 – a sentiment echoed, reworked, expanded, and cited over and over and over and over by men deciding whether or not we put our best in harm’s way in hopes of spreading that light a little further, or at least holding back the darkness a little longer.

That’s not actually the stumbling block you might think teaching high school in the 21st century. Nothing locks the minutiae of your subject into permanent recall like explaining it repeatedly throughout the years, and almost anything that doesn’t stick is easily researched when necessary. We’re still trying to get them to bring a pencil and check the class website periodically; there’s little danger they’ll without warning probe such historical depths that I end up academically cowed.

That’s not actually the stumbling block you might think teaching high school in the 21st century. Nothing locks the minutiae of your subject into permanent recall like explaining it repeatedly throughout the years, and almost anything that doesn’t stick is easily researched when necessary. We’re still trying to get them to bring a pencil and check the class website periodically; there’s little danger they’ll without warning probe such historical depths that I end up academically cowed.  Charles’s daddy, Charles VI (nice system, right?) was insane – even for royalty – and may not have been his daddy at all. The dear Queen was thought to be having an affair with the Duke of Orleans, aka the King’s brother, and he may have been Charles VII’s biological father. That would explain in part why the Queen was so cooperative with England when it came time to designate an official heir to the throne; she signed off on Henry VI holding that honor.

Charles’s daddy, Charles VI (nice system, right?) was insane – even for royalty – and may not have been his daddy at all. The dear Queen was thought to be having an affair with the Duke of Orleans, aka the King’s brother, and he may have been Charles VII’s biological father. That would explain in part why the Queen was so cooperative with England when it came time to designate an official heir to the throne; she signed off on Henry VI holding that honor.  It’s also the kind of thing which makes historians crazy, you understand. It’s just so awkward to deal with the supernatural in an academic context, especially given the typical disconnect between those book-learnin’ types and people of faith. We’d rather not talk about it at all.

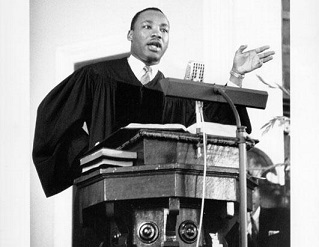

It’s also the kind of thing which makes historians crazy, you understand. It’s just so awkward to deal with the supernatural in an academic context, especially given the typical disconnect between those book-learnin’ types and people of faith. We’d rather not talk about it at all. Faith becomes a happy fluke of background rather than a key component – as if King just happened to sit next to someone randomly on the bus who ended up playing some key role we never saw coming, or left his coat too close to the oven and accidentally invented penicillin. As if taking up the call of ministry – of spreading the Word of God to the downtrodden and fighting for justice – made a nice placeholder before changing careers and fighting for civil rights.

Faith becomes a happy fluke of background rather than a key component – as if King just happened to sit next to someone randomly on the bus who ended up playing some key role we never saw coming, or left his coat too close to the oven and accidentally invented penicillin. As if taking up the call of ministry – of spreading the Word of God to the downtrodden and fighting for justice – made a nice placeholder before changing careers and fighting for civil rights. It is difficult for those of you with the slightest shred of decency to appreciate how the law and politics work. They do not operate according to anything most of us consider reasonable, moral, or even explicable. In the past they didn’t have to (and in some systems today they still don’t). Those affected had little expectation of being fully informed and no real control of the outcome.

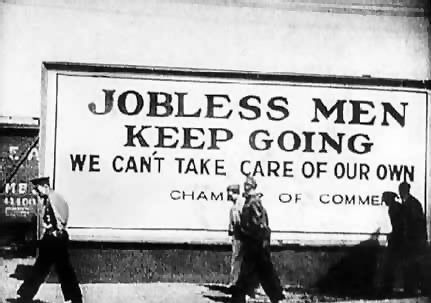

It is difficult for those of you with the slightest shred of decency to appreciate how the law and politics work. They do not operate according to anything most of us consider reasonable, moral, or even explicable. In the past they didn’t have to (and in some systems today they still don’t). Those affected had little expectation of being fully informed and no real control of the outcome. And then the South began writing the history of the war and the events which led to it. The war they’d lost. The one fought over a variety of issues, but in which slavery and its continuation were central and essential as defined by the South in the very documents they issued to justify their cause.

And then the South began writing the history of the war and the events which led to it. The war they’d lost. The one fought over a variety of issues, but in which slavery and its continuation were central and essential as defined by the South in the very documents they issued to justify their cause. What’s less tolerable is the fervent hurt and chagrin evidenced by the South’s defenders at the very suggestion that secession had ANYTHING to do with slavery. It’s not that they wish to lay out a reasoned argument, you understand – it’s that they’ve reshaped history and historiography solely through repetition and strong emotion.

What’s less tolerable is the fervent hurt and chagrin evidenced by the South’s defenders at the very suggestion that secession had ANYTHING to do with slavery. It’s not that they wish to lay out a reasoned argument, you understand – it’s that they’ve reshaped history and historiography solely through repetition and strong emotion. My favorite hockey team captain after a tough loss and horrible officiating: “There were some tough calls, but the real problem is that we didn’t take care of business in our own end. We let too many pucks get past us and didn’t take advantage of our opportunities.”

My favorite hockey team captain after a tough loss and horrible officiating: “There were some tough calls, but the real problem is that we didn’t take care of business in our own end. We let too many pucks get past us and didn’t take advantage of our opportunities.”  Of course, if the real issues were states’ rights-ish, that’s not as bad. Federalism is about balance, after all, and if perhaps the South got out of balance, that’s clearly rectified now. If anything, the central government is much stronger than originally intended as a result!

Of course, if the real issues were states’ rights-ish, that’s not as bad. Federalism is about balance, after all, and if perhaps the South got out of balance, that’s clearly rectified now. If anything, the central government is much stronger than originally intended as a result! If our ideals are as flawless and their realizations as consistent throughout our history as current legislation insists, then inequity and suffering are primarily a result of personal or cultural failures. If America is ‘exceptional’ in the way they demand we acknowledge, whatever failures have occurred within it are individual and not national. Potential solutions or cures must, logically, come from the same.

If our ideals are as flawless and their realizations as consistent throughout our history as current legislation insists, then inequity and suffering are primarily a result of personal or cultural failures. If America is ‘exceptional’ in the way they demand we acknowledge, whatever failures have occurred within it are individual and not national. Potential solutions or cures must, logically, come from the same. I’ll close with a little Bible talkin’, since that seems to be such a motivator for those pushing a better whitewashing for our lil’uns. Whatever we may disagree on, I wholeheartedly concur that we’ve lost much in our upbringing if we feel the need to run from the wisdom found in

I’ll close with a little Bible talkin’, since that seems to be such a motivator for those pushing a better whitewashing for our lil’uns. Whatever we may disagree on, I wholeheartedly concur that we’ve lost much in our upbringing if we feel the need to run from the wisdom found in