Helen Churchill Candee arrived in Gurthrie, O.T., in the mid-1890s, primarily because of the territory’s widely-advertised lax divorce laws and her desire to escape an abusive marriage. She’d come from a respectable New England upbringing and a life of some affluence, including travel, books, art, and an impressive formal education. While not necessarily an oddity in Oklahoma society, she was certainly not your average boomer.

Helen Churchill Candee arrived in Gurthrie, O.T., in the mid-1890s, primarily because of the territory’s widely-advertised lax divorce laws and her desire to escape an abusive marriage. She’d come from a respectable New England upbringing and a life of some affluence, including travel, books, art, and an impressive formal education. While not necessarily an oddity in Oklahoma society, she was certainly not your average boomer.

Her writings on Oklahoma and its people are some of the most insightful and sympathetic of her generation. Six articles and a novel, with overlapping themes and anecdotes, between 1896 and 1901. In them she covers a variety of topics comfortably, from agricultural logistics to social dynamics to government policy and how it impacts very real people—people she observed, interacted with, and developed affections for on a daily basis.

One of the most intriguing threads in this early writing is her approach towards women in Oklahoma Territory. Candee was already something of a feminist, although the term itself would have been unfamiliar to most and these leanings were not as pronounced as they’d become a few decades later. Her first book, How Women My Earn A Living, was first published in 1900, and took a socially-appropriate-but-imminently-practical approach towards ladies who found themselves in need of substantive employment. In retrospect, it’s considered something of a minor landmark in feminist literature.

Candee’s treatment of female society in the territories which is particularly fascinating. She writes with gentle candor, taking the reader into her confidence without ever quite becoming gossipy, only periodically stepping into other narrative “voices” in order to better explore her subject. Surely such forthrightness suggests we might catch occasional glimpses of the woman behind the words?

First Impressions “In Oklahoma”

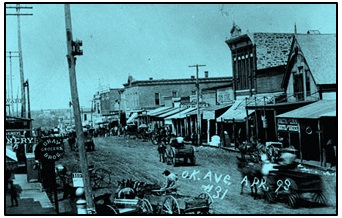

Her first piece on life in O.T., “In Oklahoma,” was for The Illustrated American, a periodical for whom she’d written regularly for several years. It was published on April 4, 1896, not long after she’d moved to the area. It’s one of the edgiest of her writings on the Territory and offers her earliest commentary on Indians, government policy, violence over disputed claims, and other themes to which she’d later return. It lacks the warmer perspective she’d have a few years later, when her affections for the Territory seem to color her portrayals of even the most unpleasant realities.

It’s also the first time she writes specifically about women in O.T.:

Among the home-seekers there were women—not helpless, discouraged women, inefficient and parasitical, but belonging to the large class who prefer work to dependence and who looked upon “proving up a claim” as a business measure, perhaps not expecting to spend all their lives in exile, but willing to conform to the time of residence stipulated by the Government, that they might sell the claim later with its improvements and realize a fair sum.

So there’s a sentence.

Candee’s contrast of O.T. home-seekers with “helpless, discouraged women, inefficient and parasitical” certainly cuts more sharply than her later works. At the risk of reading too much into one colorful phrase, perhaps this reflects a bit of her own “strength via defiance” – her own refusal to be a “helpless, discouraged woman”?

Candee was caring for two children in a frontier town. Divorce carried substantial social stigma, whatever her former society or current surroundings. There’s nothing to indicate she was in financial difficulty, but neither could she possibly have maintained in Guthrie the sort of comfort and security which had defined her world for nearly forty years. It must have taken some grit and grind in practice, however much grace and style were manifested in the presentation.

A little defensiveness or hostility is not inconceivable. It happens.

Or maybe that’s too much of a leap – inferring more than the text justifies. That also happens.

Holding Claims and Digging Out

But unless a woman is as brave as a lion and as self-sufficient as Webster’s Unabridged, it is a weary banishment. Houses are not huddled together in the territory; they are far apart, one every mile perhaps, and the majority occupied by negroes or the usual class of workers that open up the frontier, so there is no society for the woman “holding down” a claim, unless she is interested in humanity of the lowest sort.

A phrase like “brave as a lion and as self-sufficient as Webster’s Unabridged” is too golden to pass into obscurity. If only we could run about quoting it to people while shaking them by the collar enthusiastically, without getting arrested…

Her claim is probably from twelve to forty miles from the nearest railroad town; the other settlements scarcely count. And yet, inside her cabin you perhaps may see late magazines, a few books, an old Satsuma plate, some Oriental stuffs, to remind her of the world beyond the blackjacks and the rolling prairie.

More magazines than books, and a single “Satsuma plate” along with other “Oriental stuffs.” Can you feel it?

Satsuma was a type of Japanese dinnerware which could be a sign of substantial sophistication, but which was mass- produced by American factories during this time in imitation thereof. Taken together, this scattered collection acknowledges civilization, and reaches for it despite surroundings. What would prove a rather pathetic effort in other settings seems a noble declaration of values on the frontier.

Satsuma was a type of Japanese dinnerware which could be a sign of substantial sophistication, but which was mass- produced by American factories during this time in imitation thereof. Taken together, this scattered collection acknowledges civilization, and reaches for it despite surroundings. What would prove a rather pathetic effort in other settings seems a noble declaration of values on the frontier.

Candee is perfectly comfortable with the independent female accomplishing things formerly associated with men. She’d almost have to be, since she was doing it herself, and she’d certainly have encountered others in such unorthodox surroundings. And yet…

Her house began as a “dug-out”… It is getting uncomfortably near to nature’s heart to live in a square hole dug in the ground…

The dug-out is cool in summer and warm in winter, and the tireless hurricane that incessantly sweeps the territory is powerless to blow it over; but the soul of the woman longs for something more, and when the claim has yielded a profit she invests the money in a suitable house…

The “tireless hurricane that incessantly sweeps the territory”? Yeah, there’s still some edge working its way to the surface here. We’re not letting her write the state musical.

Candee’s independent woman embraces the practicalities of a dug-out, but her “soul… longs for something more” – in this case, the comforts of proper domesticity. If only we could get her, Betty Friedan, and Michelle Obama in a room together for a few hours and just… listen.

*giddy*

Changing Perspectives and Falling Plums

“Divorcons,” a piece published a week later in the periodical, is atypical. Candee writes in the fictionalized role of an “investigator” coming to Oklahoma City to “familiarize myself with the Government employés and their methods.” It ends with an editorial call for longer residency requirements before divorce can be secured, a topic possibly of some discomfort to Candee—perhaps explaining the detachment with which she writes in this unusual case.

The characters in this short piece are caricatures, alternately shadowy and one-dimensional. The “girls of easy assurance and ready tongue who bandied slang with… negroes,” the “mulatto chambermaid,” and the giggling arm-candy of businessmen in town only long enough to divorce their unseen wives before heading for Europe with their latest conquests, are hardly meant to be flattering, but neither are they presented as typical. They’re set pieces in an odd little moral noir.

Stark contrast is provided two years later when Candee wrote rather extensively of “Social Conditions In Our Newest Territory” for The Forum in June, 1898. This time it’s women in town who strive to balance gritty practicality with traditional womanhood and some appearance of high society.

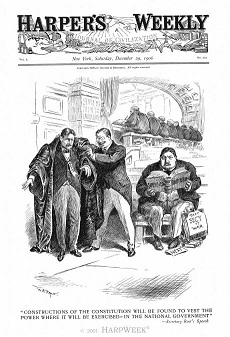

The President appoints all important officers, beginning with the Governor and extending to the judiciary, the marshalship, and minor positions. The men who occupy these offices have the privilege of making subordinate appointments in connection with their work. Each change of Administration disrupts the entire Territory; and business is temporarily paralyzed. Candidates and their aids flock to Washington, and wait on the pleasure of the President…

Local vernacular describes this condition as “waiting for plums to fall.” Except in the judicial positions, the candidates are professional or commercial men who expect to supplement their ordinary business with the duties and emoluments of Government service. Sometimes the Government at Washington delays settling the affairs of our youngest Territory; but this would never be done were it known how agonizing is the suspense in awaiting the falling of the plums.

Andrew Jackson would have been horrified, yet no doubt strangely aroused.

It comes hardest on the women, who in public maintain a dignified composure, but in private abandon stoicism and weep hysterically over the delay or the denouement.

Candee has some—but not much—sympathy for the traditionally supportive wife, flinging feelings everywhere while the men do manly things like grovel for patronage. One wonders how much her own background – the longsuffering spouse of a successful businessman, now divorced on the last frontier and proudly pushing forward on brains and style – shapes such portrayals.

Redefining Class

Later in the piece, Candee addresses the affectations of high society:

One of the most striking things in Territory society is the existence of class distinctions – more especially among the women. In business, in politics, in all the affairs of life except amusement, people are equal; but inside the parlors of the frame houses distinctions are arbitrarily made according to local standards. Occupation has little to do with it; for an auctioneer’s wife may be received, while a lawyer’s wife will be debarred.

In other words, the standards have adapted to the circumstances. Traditional social distinctions would leave most Oklahomans out of elite loops altogether, so the unwritten rules have been re-unwritten.

Young men in this country pursue any occupation by which they can life; and few of the young women lead lives of simple domesticity. All young people are at work, some of them in the humblest positions; but these things have nothing to do with the social position.

Most women in the Territory were employed in one way or another. That alone would disqualify them from high society elsewhere, but this wasn’t elsewhere. And there were few circumstances in which men of independent wealth would find themselves in Oklahoma Territory in the late 19th century.

In some places money secures the latter; but, as a rule, it is created by one of two causes,—personal magnetism, and that ultra-snobbishness which is found in its highest development in America.

So… personality and attitude? Two sides of the same shiny, annoying coin.

The extremest of conventionality marks the women, who know nothing of the delightful freedom of the women of larger cities. They live entirely within the limits of their little town; paying visits to one another. When they take their walks abroad, or drive in their buggies or surreys, it is to trot up and down the gridiron of unshaded streets; disregarding the soul-satisfying wonders of the wide prairies beyond. They become absolutely self-centered, and their views, circumscribed; but this works to the advantage of local development.

Written by a man, this would sound severe and condescending. Written by Candee, who may have partaken in some of these exact rituals, it merely seems honest – if a bit blunt. The women become sympathetic characters rather than either role-models or villains. And, as became typical of much of Candee’s writing about the Territory, they’re not entirely to blame, even for their snobbery or ignorance. They are products of their circumstances, pursuing intangible desires while accommodating very tangible limitations.

As to this “advantage of local development”…

If their eyes were always on the unattainable, whether apparel or the cultivation of the mind, there would be discontent and a tendency to scorn the simple pleasures which alone are possible. The truly feminine desire to follow the mode is evinced by the tendency to adopt new forms of expression and hospitality. Society events are reported in the local papers in the same descriptive terms as those which tell of metropolitan entertainments; and thus the people pleasantly delude themselves.

They’ve never been to Daniel Boulud’s, so they maintain a perfectly enjoyable uppity-ness over their reserved seats at Applebee’s. Accurate, perhaps – but harsh!

Moving On

“Oklahoma Claims,” published in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, October 1898, utilizes three presumably fictional characters. The narrator, a variation of Helen, acts as the bemused-but-curious traveling companion for Ollin, a well-intentioned but slightly corrupted homesteader who proudly plays the government system in his favor. They are accompanied by Leora, Ollin’s “buxom niece,” who is comically large and somewhat simple, but still wily and shameless in gaming the system herself.

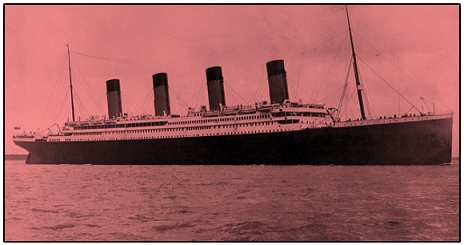

“Oklahoma” (The Atlantic Monthly, September 1900) and “A Chance In Oklahoma” (Harper’s Weekly, February 23, 1901) are arguably the strongest of the six pieces, but neither speaks of women other than in passing. Whether this is an intentional shift or the discussion simply falls outside the primary focus of each piece, they add little to this particular equation.

We’re left to Candee’s other works to better understand her and her approach towards the complex sex. As to women in early Oklahoma, we’ll simply have to seek further information in far less-entertaining accounts.

Helen Churchill Candee was born in 1858 as Helen Churchill (her mother’s maiden name) Hungerford of New York. Her father was a successful merchant, and Helen grew up in relative comfort both there and in Connecticut where the family moved shortly thereafter. More important than the physical provisions prosperity allowed, she was exposed to ideas and stories, music and art, history and culture, in ways unlikely to have been possible had she lived a generation before, or anywhere else.

Helen Churchill Candee was born in 1858 as Helen Churchill (her mother’s maiden name) Hungerford of New York. Her father was a successful merchant, and Helen grew up in relative comfort both there and in Connecticut where the family moved shortly thereafter. More important than the physical provisions prosperity allowed, she was exposed to ideas and stories, music and art, history and culture, in ways unlikely to have been possible had she lived a generation before, or anywhere else.  Oklahoma Territory had them all beat, however. Ninety days – that’s how long you needed to establish residency. Three short months and you were eligible to file. If your soon-to-be ex didn’t show, the court appointed someone to speak on his or her behalf, whether they knew their “client” or not. Generally, things were wrapped up in time to grab some lunch before getting back to watching lazy hawks circle in the sky and whatnot.

Oklahoma Territory had them all beat, however. Ninety days – that’s how long you needed to establish residency. Three short months and you were eligible to file. If your soon-to-be ex didn’t show, the court appointed someone to speak on his or her behalf, whether they knew their “client” or not. Generally, things were wrapped up in time to grab some lunch before getting back to watching lazy hawks circle in the sky and whatnot. Between 1896 and 1901, Candee wrote six pieces for five different periodicals about Oklahoma Territory and life therein. They’re strong enough to consider individually, but what they demonstrate consistently is her knack for capturing things like crop production reports and detached observations on cultural evolution while always circling back to the human experience that makes all the rest of it matter.

Between 1896 and 1901, Candee wrote six pieces for five different periodicals about Oklahoma Territory and life therein. They’re strong enough to consider individually, but what they demonstrate consistently is her knack for capturing things like crop production reports and detached observations on cultural evolution while always circling back to the human experience that makes all the rest of it matter.

If for some strange reason you’ve not already read

If for some strange reason you’ve not already read  Helen Churchill Candee came to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory (O.T.) in the mid-1890s, primarily drawn by its

Helen Churchill Candee came to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory (O.T.) in the mid-1890s, primarily drawn by its  Candee moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, for several years, writing regularly for periodicals back east. It was around this time she published her first two books – How Women May Earn A Living and An Oklahoma Romance. The first became a landmark in women’s literature (a subject for another time) and the second – her only work of fiction out of the many successful books she’d continue to write – helped publicize and glorify life in the recently opened territory.

Candee moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, for several years, writing regularly for periodicals back east. It was around this time she published her first two books – How Women May Earn A Living and An Oklahoma Romance. The first became a landmark in women’s literature (a subject for another time) and the second – her only work of fiction out of the many successful books she’d continue to write – helped publicize and glorify life in the recently opened territory.

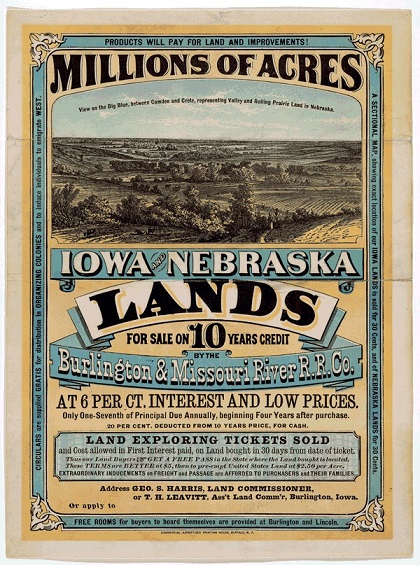

At that moment, it was still all about land – farming, growing, raising, living land. And this was it. Everything else was pretty much taken. The bar was closing and the men outnumbered the women 3 to 1. Time to make your play.

At that moment, it was still all about land – farming, growing, raising, living land. And this was it. Everything else was pretty much taken. The bar was closing and the men outnumbered the women 3 to 1. Time to make your play.  The allotment size was consistent with the Homestead Act from way back in 1862, signed by Lincoln during the Civil War. This was considered a sufficient spread to allow a homestead and plenty of planting land. A free man working without modern equipment would be unlikely to cultivate more than this productively.

The allotment size was consistent with the Homestead Act from way back in 1862, signed by Lincoln during the Civil War. This was considered a sufficient spread to allow a homestead and plenty of planting land. A free man working without modern equipment would be unlikely to cultivate more than this productively.  How many others in that generation and prior had taken their shots, staked their claims, virtually everywhere else in the West? Those waiting now were the also-rans, the coulda-beens, desperate for one last chance at stepping into the role of Yeoman Farmer in the most democratic manifestation of the ideal. Redemption? Maybe so.

How many others in that generation and prior had taken their shots, staked their claims, virtually everywhere else in the West? Those waiting now were the also-rans, the coulda-beens, desperate for one last chance at stepping into the role of Yeoman Farmer in the most democratic manifestation of the ideal. Redemption? Maybe so.