Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About the Many Causes of the Civil War

Three Big Things:

1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery.

1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery.

2. The Election of 1860. Abraham Lincoln’s victory signaled to the South that the system – democracy, compromise, voting – no longer worked. Their voice, it seemed, was no longer even a factor in how the nation was run. Lincoln’s election was the final straw, since he was perceived as a threat to… what else? Slavery.

3. Overconfidence. Few on either side anticipated the possibility of an extended war, or the kinds of death and violence which were to come. Had those making decisions had any hint of what would unfold, one wonders if they’d have pursued other solutions a bit more vigorously.

Slavery

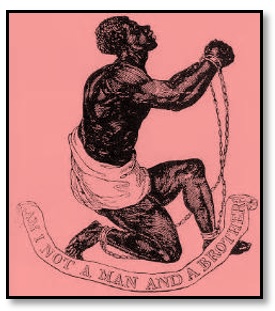

Even before declaring independence in 1776, slavery had been a controversial topic in the American colonies, but it was not a strictly North/South issue. Slavery was legal in most of the original thirteen states, and abolitionists – while not always prominent – spoke out against it up and down the young nation.

Over time, the North became increasingly industrialized while the South grew more and more reliant on large-scale cash crops. Small farmers were still the norm everywhere, but most large cities were in the North, and most plantations were in the South. Slavery ceased to make economic sense in the North, allowing ideological concerns to eventually prohibit it altogether. As the cotton gin made the institution wildly profitable and seemingly essential to the South, slavery was increasingly promoted as a positive good for all involved – including the slaves themselves.

North and South had more in common than not, but basic geography meant they developed into two very different economies and cultures. By the 1820s and 1830s, during the first Age of Reform, abolitionists speaking out against slavery were quick to condemn not only the institution, but those perpetuating it. Not appreciative of being labeled backwards, horrible people – especially by self-righteous Yankees – the South struck back with criticisms of northern corruption and hypocrisy. It was no longer about the economy or even American ideals – it was personal.

Counting Down to Civil War

Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.

Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.

The Missouri Compromise (1820): Missouri, which had slavery, was ready for statehood. This would have thrown off the balance between slave and free states in the Senate (the North held a decisive advantage in the House). Maine was created and admitted at the same time, and an imaginary line drawn west – above it would be forever free, below it not so much. This delayed major conflict over slavery for almost a generation.

Annexation of Texas (1845): When Texas joined the Union, it was a natural slave state, and below the line, but it was huge. There was talk of admitting it as multiple states – maybe as many of five. The resulting war with Mexico was largely supported by pro-slavery folks, with far less enthusiasm emanating from “free-soilers” in the North.

The Compromise of 1850: Thanks to rich soil and the Gold Rush, California filled up quickly. When it was ready to enter the Union, the national scab was picked off yet again. Congress put together a package of five bills hoping to appease both sides. California would be free. Some Texas boundaries were settled. Washington, D.C., would eliminate the slave trade but keep slavery itself. Utah and New Mexico would be organized on the basis of “popular sovereignty” (we’ll come back to that). But the most important part of this compromise was the Fugitive Slave Act.

The Fugitive Slave Act (1850): Technically, slaves escaping to the North were still legally slaves and subject to return (this was even in the U.S. Constitution). But it was rarely enforced, and if you made it North, you were essentially free. The FSA gave this expectation teeth, making it illegal to refuse assistance to authorities or others looking to recapture runaways. The effect was very different than intended – while most Northerners were against slavery, they were generally busy with their daily lives and most did little or nothing about it one way or the other. This law got them involved – mostly by actively assisting runaways or harassing and misleading slave catchers.

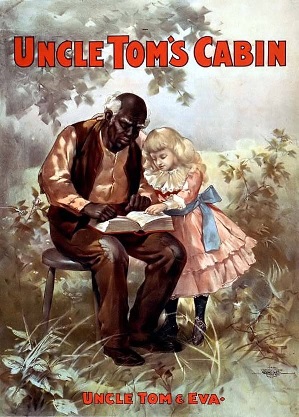

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.)

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.)

The Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854): Legislation by Stephen Douglas (the one who’ll run against Lincoln in a few years) which allowed Kansas and Nebraska to decide the slavery issue via “popular sovereignty” – letting the people decide. This sounded very democratic, but in practice it only laid the groundwork for…

“Bleeding Kansas” (1856): People from both sides poured in and took up residence in preparation for the vote. Violence ensued, towns were burned, and there was much name-calling. John Brown showed up with his followers and beheaded several pro-slavery settlers with swords while forcing their families to watch. Things were… tense.

“Bleeding Sumner” (1856): Senator Charles Sumner gave a provocative speech about slavery, calling it a “harlot” to whom various southern politicians were bound. Preston Brooks of South Carolina took exception, and shortly thereafter surprised Sumner at his desk where he proceeded to beat his brains out (almost literally) with his cane. Sumner survived, but was forever impaired. The North was horrified, but Brooks became a hero to the South.

Scott v. Sandford (1857): Would a slave who’d lived in a free state or free territory become legally free as a result? The Supreme Court said NO. The majority opinion by Chief Justice Roger Taney added that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in territories, and Blacks couldn’t bring suit to begin with because they weren’t citizens – any of them. This is considered one of the worst and most unnecessarily over-reaching decisions in all of Supreme Court history.

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates (1858): Lincoln and Douglas both wanted the same Senate seat in Illinois. They traveled the state holding outdoor debates, well-attended and quite colorful. Lincoln wasn’t new to politics, but this is when he became a household name saying things like “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; I do not expect the house to fall; but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…”

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…”

The Election of Abraham Lincoln (1860): Four major candidates including Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln won the Electoral College without winning a single southern state. By the time Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861, seven southern states had seceded. (Four more left after the actual fighting started.)

You Wanna Sound REALLY Smart? {Extra Stuff}

The Battle of Ft. Sumter (April 12, 1861): As the nation divided, people from or loyal to the North who happened to be in the South made their way home, as did Southerners who happened to be up North. Forts and other military sites located in the South were largely left in the hands of those determined to take up arms for the Confederacy, except for one – Ft. Sumter in Charleston Bay, South Carolina. Major Robert Anderson, despite being low on supplies and having zero chance of military success, held his post.

One of the first things greeting Lincoln upon taking office was a telegraph from Anderson requesting orders – would he be resupplied? If not, he’d be forced to surrender in a few days. Lincoln sought middle ground in his attempt to resupply Anderson. If he gave up the fort, he’d appear weak. If he didn’t, he’d be responsible for starting the war most thought inevitable at this point. He attempted to send in supplies but not additional military aid; P.T. Beauregard and crew opened fire early morning, April 12th.

The battle raged most of the day, mostly cannon fire exchanged to and from the fort. At the end, Anderson surrendered with honor. It was the first real fighting of the Civil War, and… no one died. There were zero serious casualties until a cannon exploded during an honor salute to the flag after the fort had surrendered and two soldiers were killed. This war was going to be weird.

From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address:

From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address:

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States, that by the accession of a Republican Administration, their property, and their peace, and personal security, are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension… I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so…

Before entering upon so grave a matter as the destruction of our national fabric, with all its benefits, its memories, and its hopes, would it not be wise to ascertain precisely why we do it? Will you hazard so desperate a step, while there is any possibility that any portion of the ills you fly from, have no real existence? … Will you risk the commission of so fearful a mistake? …

Physically speaking, we cannot separate. We cannot, remove our respective sections from each other, nor build an impassable wall between them. A husband and wife may be divorced, and go out of the presence, and beyond the reach of each other; but the different parts of our country cannot do this. They cannot but remain face to face; and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them…

My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and well, upon this whole subject. Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time… Intelligence, patriotism, Christianity, and a firm reliance on Him, who has never yet forsaken this favored land, are still competent to adjust, in the best way, all our present difficulty.

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict, without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect and defend” it.

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.

In that same hour, of course, I can ask the entire class which way is east on a map of Africa and nearly spark panic because they hadn’t realized there would be a “quiz” over this particular topic. They’re brilliant and ignorant, interested and bored, richly steeped in the strangest historical folderol and lacking critical foundations for basic historical understanding.

In that same hour, of course, I can ask the entire class which way is east on a map of Africa and nearly spark panic because they hadn’t realized there would be a “quiz” over this particular topic. They’re brilliant and ignorant, interested and bored, richly steeped in the strangest historical folderol and lacking critical foundations for basic historical understanding.

Do you ever start off intending to write about one thing and no matter how much you try to stay on target, you keep shooting off an entirely different direction like a blog grocery cart full of one item and with a bad wheel (*squeak lurch squeak squeak lurch*) and although you’re desperately trying to steer back to what you set out to write about, you just… can’t – at least not until you’re so close to your max word count that there’s no point?

Do you ever start off intending to write about one thing and no matter how much you try to stay on target, you keep shooting off an entirely different direction like a blog grocery cart full of one item and with a bad wheel (*squeak lurch squeak squeak lurch*) and although you’re desperately trying to steer back to what you set out to write about, you just… can’t – at least not until you’re so close to your max word count that there’s no point?