Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About the Boers & the First Boer War

Three Big Things:

1. The Boers were white descendants of Dutch, German, and French Protestants who settled the Cape of Good Hope in the mid-17th century. They were farmers and ranchers who believed they were among God’s most favored elect.

2. There were two distinct wars between the Boers and the British – the Boers won the first using superior horsemanship and marksmanship combined with a willingness to run and hide.

3. Neither side thought much of native Africans, who were attacked, enslaved, or exploited as necessary to achieve Boer or British goals. This created some long-term racial tensions in Southern Africa.

Background

In 1652, the Cape of Good Hope was colonized by the Dutch, largely as a coastal supply station for ships traveling from Europe to Asia. While the Age of Exploration had initially been dominated by the Portuguese and Spanish, by the late 16th century the British and Dutch had stepped up their imperialism games substantially. Even old New York (in the American colonies) was once New Amsterdam.

In short, the Dutch were a thing.

Settlers of what became known as the “Cape Colony” included a group of farmers known as “Boers” – the Dutch word for “farmer.” (Clearly the Dutch didn’t feel the need to get super-creative with monikers.) A majority were Dutch, but a substantial minority were Germans or Huguenots (French Protestants who emigrated to escape severe persecution by France’s Catholic majority). They were gritty and self-reliant and chosen by God – how many of us can claim that?

The Sun Never Sets

Great Britain first became an annoyance when they seized control of the Cape Colony in 1806. You may recall a feisty French fellow by the name of Napoleon who was trying to take over the world at the time. Holland had been seized by the French and was thus technically part of Napoleon’s empire, making Dutch colonies fair game in the eyes the British, who figured if anyone was going to run the entire world, it should probably be them.

The British weren’t yet in full “imperialism” mode, but they did seem to keep trickling in. They seemed eager to share their political and cultural superiority with those less evolved – which was most people. They criticized the Boers for having slaves, a practice only recently abolished by Parliament. As they became a majority, their colonial government declared English the official language of the Cape, prohibiting the use of Dutch in legal transactions or public affairs. None of these proved effective ways to make friends.

Not that the Boers were particularly collegial themselves. Neither side was prone to compromise when it came to faith, government, or culture, and about the only thing they could agree on was that native black Africans were the worst. The British were simply no longer willing to openly enslave them, preferring less direct methods of control and exploitation in order to appease moral sentiments back home. The Boer, on the other hand, were home. For now.

Boer Trek: The Next Generation

A few Boers had already migrated north over the years, encouraged by a climate favorable for farming and raising livestock, as well as the relatively low rate of excruciating deaths by indigenous diseases. As the British began dominating the Cape Colony, this migration increased dramatically. Between 1835 and 1846, nearly 15,000 Boers moved northeastward as part of “The Great Trek,” primarily in covered wagons drawn by oxen.

As they’d migrated, the Boers enslaved or otherwise marginalized the rather sparse native (and black) African population and over time considered themselves very much the “real” citizens who deserved to be there, as opposed to the (British) interlopers who eventually followed and with whom they continued to clash. Their convictions were reinforced by their intense Calvinistic faith. The Boers saw themselves as a chosen people – as trekboeren (“diasporic farmers”). Like modern day Israelites, they kept to themselves and largely ignored or rejected the rapid changes sweeping Europe – the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution, for example – as beneath them.

I know, I know – wacky, right? But so goes history.

By this time, they had another name – “Afrikaners,” from “Afrikaans,” the primary language of the Boers – a derivative of Dutch shaped by various African languages and local inflections over the years. The term is often used interchangeably with “Boers” just to keep history as confusing as possible.

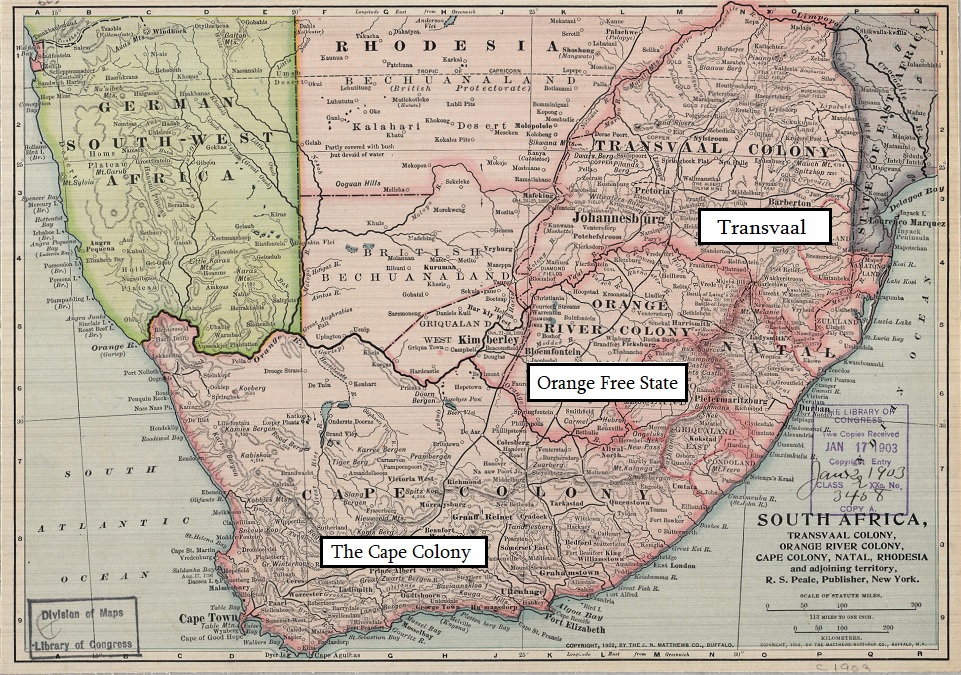

The Boer Republics

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of.

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of.

For a decade or two, it seemed the Boer Republics might just remain the lands that time, technology, and the rest of the world forgot. In the late 1860s, however, diamonds were discovered along the border between Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and the British-controlled Cape Colony. The Orange Free State agreed to relinquish their claims in exchange for compensation by the British, but the Transvaal insisted the region was fully theirs. And it probably was.

Still, anyone paying even minimal attention in high school history recognizes that it doesn’t matter what governments say or what agreements have been signed once mineral wealth is revealed in any meaningful quantity. Besides, the Transvaal Boer lacked the industrial backgrounds or manpower to exploit such a find on their own; they pretty much had to let others in if they were to take full advantage. Enter the Uitlanders.

These British fortune-hunters (or “outlanders”) soon outnumbered the locals and began demanding greater political participation and basic protections. Factions rose up and clashed, tensions increased, and in 1877 the British officially annexed the Transvaal Republic. The Transvaal Boers accepted this arrangement because of a mutual enemy – the Zulu. Once the resulting Anglo-Zulu War in 1879 resolved that threat, however, the Boer resumed complaining about their rights being violated and all the other usual stuff. They declared independence from the British in December of 1880.

The First Boer War, aka “The Transvaal Rebellion” (1880 – 1881)

The Boer didn’t have a standing army. They used what was known as a “commando system,” which despite the cool name had more in common with the methods of the Ancient Greeks than it did Rambo movies. All male citizens between the ages of 16 and 60 were expected to report for militia duty, bringing their own horses, weapons, and food. They elected their own officers and eschewed formal uniforms.

These were hunters on the African veldt (“grasslands”), dressed in earth tones, accustomed to hiding in the most limited available cover, and taught by long experience that if you missed with your first shot, you were going vegetarian that evening. When the fighting went mobile, their skills on horseback were comparable to the tribes of the North American Great Plains or the Mongols of a few centuries before. They carried the convictions of Calvinism alloyed with the stubborn patience of generational farmers in a hostile land.

The British, on the other hand, were sporting those same bright red coats and frilly tactics you remember from the American Revolution. They rode horses, of course, but as a military skill, not a way of life. The result was about what you’d expect in those circumstances.

The First Boer War was Great Britain’s first military defeat since 1783, and an embarrassment of international scale. It didn’t help that such a high percentage of the forces who’d so dramatically triumphed seemed to be teenagers and old men.

Transvaal (aka “the South African Republic”) secured its independence in March of 1881, at least for a time. Great Britain settled on claiming “suzerainty” – a form of territorial control in which a people or region remains technically independent while in practice somewhat subservient to the stronger nation. European powers of this era generally avoided outright conquering and control of the areas they colonized, preferring instead to “exert influence” through less overt methods – thus giving themselves some degree of deniability concerning the fates of those they imperialized and giving themselves some “wiggle room” as power dynamics continued to evolve in places like, say… the Boer Republics.

And evolve they did. In the 1880s, the so-called “Scramble for Africa” began. This was a divvying up of sorts of the entire continent by European and other powers, who actually met in Berlin in 1884 to map out who would get what – a process largely responsible for the map of Africa as it looks today. It was done without reference to traditional divisions or tribal boundaries, a neglect made easier by the complete absence of anyone actually from Africa – including the Boers – at the conference.

So it wasn’t long before, once again, things weren’t looking too good for the Afrikaners. One way or the other, there was going to be another war.

1.The Olmec are generally considered the foundational civilization of Mesoamerica – the region now hosting southern Mexico and Central America. They were the cultural forefathers of later, more familiar peoples like the Mayans and Aztecs.

1.The Olmec are generally considered the foundational civilization of Mesoamerica – the region now hosting southern Mexico and Central America. They were the cultural forefathers of later, more familiar peoples like the Mayans and Aztecs. Another first was the Olmec love of chocolate. They drank this delicacy as far back as 1900 BCE, before they were even a presence on the world stage. Cacao beans require extensive processing before consumption, and taste very little like what the average westerner thinks of as “chocolate” today. After being ground into powder, they were mixed with a variety of things, from flowers or honey to maize or chili peppers. Ideally, the result was then stirred into hot water and whipped into a froth before joyfully imbibing.

Another first was the Olmec love of chocolate. They drank this delicacy as far back as 1900 BCE, before they were even a presence on the world stage. Cacao beans require extensive processing before consumption, and taste very little like what the average westerner thinks of as “chocolate” today. After being ground into powder, they were mixed with a variety of things, from flowers or honey to maize or chili peppers. Ideally, the result was then stirred into hot water and whipped into a froth before joyfully imbibing. 1. The Stock Market “Crash” (October 29th, 1929) marked the beginning of the biggest, longest, worstest, economic and emotional depression in all of U.S. History. It impacted most of the rest of the world as well.

1. The Stock Market “Crash” (October 29th, 1929) marked the beginning of the biggest, longest, worstest, economic and emotional depression in all of U.S. History. It impacted most of the rest of the world as well. 4. Crop prices plummeted. Before it quit raining, farmers were producing a wider variety of crops more efficiently than ever before. That worked out well during WWI because soldiers gotta eat, and the U.S was on a team with lots of nations, all of whom had soldiers to feed as well. When the war ended, however, prices dropped dramatically. Being hard-working, rugged individual-types, most farmers doubled down and worked harder, planted more land, or borrowed money to acquire even more machinery, fertilizer, etc. It worked – they grew even more food – and thanks to basic supply and demand, made even less money as a result.

4. Crop prices plummeted. Before it quit raining, farmers were producing a wider variety of crops more efficiently than ever before. That worked out well during WWI because soldiers gotta eat, and the U.S was on a team with lots of nations, all of whom had soldiers to feed as well. When the war ended, however, prices dropped dramatically. Being hard-working, rugged individual-types, most farmers doubled down and worked harder, planted more land, or borrowed money to acquire even more machinery, fertilizer, etc. It worked – they grew even more food – and thanks to basic supply and demand, made even less money as a result. The Trigger – “Black Tuesday”

The Trigger – “Black Tuesday” FDR’s regular “Fireside Chats” – Radio time spent speaking directly to the American people – offered a sense of unity and hope which forever changed expectations of a President in times of need. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt also published a regular column in which she responded to letters from those seeking assurance or aid.

FDR’s regular “Fireside Chats” – Radio time spent speaking directly to the American people – offered a sense of unity and hope which forever changed expectations of a President in times of need. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt also published a regular column in which she responded to letters from those seeking assurance or aid. 1. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton – Denied the right to participate in the first “World’s Anti-Slavery Convention” in London in 1840, Mott and Stanton decided that if women were to be effective reformers, they’d need more rights themselves. They spearheaded the first “women’s rights convention” on record in Seneca Falls, NY, eight years later.

1. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton – Denied the right to participate in the first “World’s Anti-Slavery Convention” in London in 1840, Mott and Stanton decided that if women were to be effective reformers, they’d need more rights themselves. They spearheaded the first “women’s rights convention” on record in Seneca Falls, NY, eight years later. The Quakers believed in the “priesthood of all believers,” a particularly Protestant sort of Protestantism which meant the church as an institution went easy on the doctrinal details or authority of the clergy and heavy on the relationship with Jesus and personal Bible study. Their belief in the value of all individuals meant they were some of the earliest abolitionists and tended to be strong proponents of women’s rights. There was thus considerable support for the idea of a “women’s rights convention” from Quakers – both women and men – in the Seneca Falls area.

The Quakers believed in the “priesthood of all believers,” a particularly Protestant sort of Protestantism which meant the church as an institution went easy on the doctrinal details or authority of the clergy and heavy on the relationship with Jesus and personal Bible study. Their belief in the value of all individuals meant they were some of the earliest abolitionists and tended to be strong proponents of women’s rights. There was thus considerable support for the idea of a “women’s rights convention” from Quakers – both women and men – in the Seneca Falls area. Day Two largely followed up on these same two documents, but with men allowed to participate this time, and there were discussions of other legalities and practicalities. Those present signed the final forms of the Declaration and the Resolutions, and there were more speeches rousing the crowd to action and on towards victory and so on and it was apparently all quite inspirational.

Day Two largely followed up on these same two documents, but with men allowed to participate this time, and there were discussions of other legalities and practicalities. Those present signed the final forms of the Declaration and the Resolutions, and there were more speeches rousing the crowd to action and on towards victory and so on and it was apparently all quite inspirational. 1. The North had more of everything except capable military leadership. They also weren’t fighting to defend their home states, their farms or families, or their overly-romanticized “way of life.” Despite Lincoln’s best efforts, the North kept finding ways to lose for most of the first half of the war.

1. The North had more of everything except capable military leadership. They also weren’t fighting to defend their home states, their farms or families, or their overly-romanticized “way of life.” Despite Lincoln’s best efforts, the North kept finding ways to lose for most of the first half of the war.