Three Big Things:

1. The Xhosa were a South African people threatened by European encroachment beginning in the 17th century.

2. In 1856, a young Xhosa girl encountered two supernatural strangers who told her a time of renewal was coming but must be preceded by the slaughter of their existing cattle and crops.

3. The resulting Cattle-Killing Movement left the Xhosa destitute and divided against themselves. Over a century and a half later, they remain one of South Africa’s poorest demographics.

Background

The Xhosa were (and are) a major cultural group from the Eastern Cape. The land was fertile and there were plenty of fresh water sources for their cattle – which, as it turns out, were rather important to them. Like the Zulu, they were descended from the Bantu who centuries before had migrated from the northwest. Xhosa is still one of the most-spoken languages in Africa, and the native tongue of Nelson Mandela, Bishop Desmond Tutu, and the Black Panther.

The Xhosa were (and are) a major cultural group from the Eastern Cape. The land was fertile and there were plenty of fresh water sources for their cattle – which, as it turns out, were rather important to them. Like the Zulu, they were descended from the Bantu who centuries before had migrated from the northwest. Xhosa is still one of the most-spoken languages in Africa, and the native tongue of Nelson Mandela, Bishop Desmond Tutu, and the Black Panther.

The community unit was the “district,” made of extended family “homesteads.” Each district was led by a chief whose power was balanced by the expectation he would guide and protect the district. The chiefs answered to a Xhosa king, to whom they were usually related in some way, and whose power – like theirs – was contingent on perceptions of his success.

Manipulations of or by evil spirits were thought to be the source of all sorts of trouble by the Xhosa. Illness, poor crops, natural disasters – witchcraft was always a suspect. It didn’t have to be the immediate source; merely tolerating it, whatever its form, led to disasters. Fortunately, family ancestors properly honored acted as good spirits, offering guidance how to refute the evil. One of the most common ways was through sacrifice. A variety of animals were used, but by far the most sacred were cattle.

Cattle were everything to the Xhosa. They were sustenance – milk and meat – as well as a source of hides, tools, fuel, and fertilizer. They were also currency – the central unit of value understood by all. They indicated status and they purchased wives. Minor crimes could be forgiven for what we’d think of as a small “fine,” generally paid to the chief in the form of – you guessed it – cattle.

Conflict & Crises

Since the mid-17th century, the Xhosa, like the rest of Southern Africa, had been forced to accommodate European settlers on the Cape – first the Dutch, then the British. The Dutch Boers were especially problematic. Staunch Calvinists, they believed themselves quite literally chosen by God and rarely hesitated to transgress on Xhosa territory. In turn, the Xhosa raided Boer settlements for (what else?) cattle, and hostilities erupted regularly.

Since the mid-17th century, the Xhosa, like the rest of Southern Africa, had been forced to accommodate European settlers on the Cape – first the Dutch, then the British. The Dutch Boers were especially problematic. Staunch Calvinists, they believed themselves quite literally chosen by God and rarely hesitated to transgress on Xhosa territory. In turn, the Xhosa raided Boer settlements for (what else?) cattle, and hostilities erupted regularly.

Since 1779, the Xhosa had been engaged in hostilities with the Boer and the British – sometimes united, sometimes separately. Historians divide this century into nine distinct wars, the eighth of which lasted from 1850 – 1853 and primarily involved the British. It was rooted in ugliness on both sides, but one interesting element was a Xhosa prophet who predicted the tribe would be completely unaffected by the colonists’ bullets.

He was incorrect. It was the most devastating loss of the century for the Xhosa.

In 1854, “lungsickness” began spreading through the Xhosa cattle. It was brought from Europe by Boer ranchers looking to improve their herds with imported stock. The disease decimated Xhosa herds, leaving the community hungry, destitute, and looking for answers. What they were certain of was that their physical suffering reflected a commensurate spiritual corruption on the part of those responsible.

The Prophecy

Nongqawuse was a 15-year old Xhosa girl whose uncle, Mhlakaza, was a respected diviner and advisor to King Sarhili. In April 1856, Nongqawuse and a friend walked to the banks of the Gxarha River, near the Indian Ocean, to scare away birds who sometimes threatened family crops there. It was an area of indescribable natural beauty – the river, the ocean, farmland, bushes, and cliffs, making it something of an Eden in otherwise dark times for the Xhosa.

There, the girls met two strangers who claimed to be ancestor-spirits and proceeded to explain that the Xhosa dead would soon rise and a new era of supernatural prosperity would begin. They were to tell their people to abandon all forms of witchcraft, incest, and adultery, and begin preparing enclosures for the many new cattle about to appear and fields for the bountiful crops about to spring forth.

They would, of course, first have to destroy all existing crops and cattle to make way for this renewal. They were contaminated anyway – corrupted, both literally and spiritually. For things to become new, the old must pass away. So, let’s go kill those cows. All of them.

The homestead was understandably hesitant to embrace this revelation, so Mhlakaza returned with the girls to the site of the visitation. The strangers would only communicate through Nongqawuse (which perhaps should have been a red flag) but Mhlakaza was nonetheless convinced one of the spirits was, in fact, his deceased brother, and embraced the prophecy wholeheartedly. Mhlakaza sent word to the other chiefs, and soon the entire nation was talking. Even King Sarhili sent trusted family members to investigate; soon he, too, was officially a believer.

The homestead was understandably hesitant to embrace this revelation, so Mhlakaza returned with the girls to the site of the visitation. The strangers would only communicate through Nongqawuse (which perhaps should have been a red flag) but Mhlakaza was nonetheless convinced one of the spirits was, in fact, his deceased brother, and embraced the prophecy wholeheartedly. Mhlakaza sent word to the other chiefs, and soon the entire nation was talking. Even King Sarhili sent trusted family members to investigate; soon he, too, was officially a believer.

Reactions across the kingdom were mixed; some embraced it immediately, eager to bring about a newer, better world. Others rejected it entirely, declaring it foolish to destroy an already inadequate source of sustenance. Most were somewhere in between, not wanting to commit wholeheartedly to such extremism, but afraid to anger the ancestors or incur censure from the community. Perhaps not surprisingly, districts hit the hardest by lungsickness, or who’d recently lost land to white encroachment, tended to more readily embrace the call to radical action.

Muddy Waters & Collapse

In the twelve months preceding Nongqawuse’s revelation, there had been multiple prophecies involving a “black nation across the sea” who would soon be coming to the aid of the Xhosa. In preparation, their messengers declared, the Xhosa should destroy their fields and kill their cattle, then prepare for newer, better crops and livestock.

Sound familiar?

These prophecies referred to the Russians, then currently engaged in the Crimean War against the British and others, and who were thought to be both supernatural and black-skinned by much of South Africa. Nongqawuse’s vision, which implied the removal of Brits and Boers but never mentioned them directly, renewed interests in these prior predictions, bringing an explicitly anti-white tone to the discussion by association.

As the months dragged on without the dead rising or the cattle returning, adherents to Cattle-Killing began blaming non-believers for the failure of the prophecy, sometimes killing their cattle and destroying the crops clandestinely to help speed the renewal. Other Xhosa had sold their cattle in order to avoid looking like non-believers, but this, too, was betrayal, since appropriate sacrificial rituals were essential to the purification required.

The more evident it became that renewal was not forthcoming, the more committed and dogmatic the faithful became – a tragic pattern in these sorts of things. Even if the entire community had reversed course, however, it was too late for any real hope of recovery. They had simply destroyed too much of the foundational elements of their way of life – arable land and healthy cattle.

In February 1857, King Sarhili met with Nongqawuse and Mhalakaza at the site of the original vision, where they spoke privately for a long (but unspecified) amount of time. He then announced that the promised New World would begin in exactly eight days, with a blood-red sunrise and a massive storm, during which only the homes of true believers would remain standing and the colonizers would return to the sea. Finally, the dead would begin rising, the crops begin growing, and the new and improved cattle return.

Sarhili’s proclamation prompted a final week-long spasm of crop destruction and cattle-slaughter, until the eighth day arrived. It was a normal sunrise, and the weather was mild.

Aftermath

Reactions to Nongqawuse’s cattle-killing prophecy fragmented not only districts, but homesteads and families. In the resulting destitution, something in the neighborhood of 40,000 Xhosa died of starvation, illness, and related violence. The British-controlled Cape began offering assistance to Xhosa willing to move to the colony under special labor contracts. They had to agree to work anywhere in the colony for whatever amount of money was offered in order to receive food, medical care, or other relief. The Boer, on the other hand, had little use for such subtleties and simply continued enslaving or killing the Xhosa as circumstances allowed.

The Eastern Cape never fully recovered. Today, “Nongqawuse” is a byword – brought up whenever someone’s ideas are considered especially foolish or destructive. The destruction visited on the Xhosa by what they perceived as the white man’s God convinced many they should try to get on his good side instead. In 1850, there were almost no self-identified Christians among the Xhosa; a century later it was the area’s majority faith.

It’s easy to paint the Cattle-Killing Movement as self-destructive, but that over-simplifies the dynamics and the desperation of those involved. Many mainstream belief systems promote narratives in which sacrifice and apparent foolishness lead to spiritual (and sometimes temporal) victory. Jesus had an opportunity to establish an earthly kingdom but chose death on a cross in exchange for something longer-term. Gandhi protested British imperialism with a Salt March, at the end of which he and his followers were severely beaten – but which changed British policy. Obi Wan fell before Darth Vader, warning him that “if you strike me down, I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine”; he came back as a hologram who could no longer be blamed for subsequent plots.

The whole nature of faith is that you don’t actually know that what you’re doing will work. The “God-Worshippers” were taking part in the Taiping Rebellion at almost the same time the Xhosa were killing their cattle. The “Ghost Dance” Movement of the Plains Amerindians and the Boxer Rebellion were a half-century later. Even today there are evangelicals thrilled at their perception that President Donald Trump is hastening the end of the world through his foreign policy choices, believing that imminent destruction for the rest of us means a new and better plane of existence for them, the chosen few.

Right or wrong, radical faith like that of the cattle-killing Xhosa was an act of defiance and hope when less-extreme measures had proven inadequate. That it didn’t work – at least by our mortal standards – makes it no less true.

Nevertheless, with so much gold came more Uitlanders – ambitious individuals as well as foreign companies with the resources and know-how to manage difficult extraction. The Transvaal government made it difficult for newcomers to vote or otherwise fully participate in society, which didn’t bother those only interested in quick profits but antagonized the British to their ideological cores.

Nevertheless, with so much gold came more Uitlanders – ambitious individuals as well as foreign companies with the resources and know-how to manage difficult extraction. The Transvaal government made it difficult for newcomers to vote or otherwise fully participate in society, which didn’t bother those only interested in quick profits but antagonized the British to their ideological cores. The Jameson Raid reinforced to the Boer the importance of sticking together – supporting one another while constraining the Uitlanders. Tensions continued to build for several more years and eventually the British resorted to a more traditional approach and began building up troops along the border. In October of 1899, President Paul Kruger issued an ultimatum demanding they withdraw.

The Jameson Raid reinforced to the Boer the importance of sticking together – supporting one another while constraining the Uitlanders. Tensions continued to build for several more years and eventually the British resorted to a more traditional approach and began building up troops along the border. In October of 1899, President Paul Kruger issued an ultimatum demanding they withdraw. The Anglo’s perceived brutality severely damaged their standing in the eyes of the rest of the world as well as provoking outrage and protests back home. The war became increasingly unpopular as it continued to drag on, prompting the British to offer increasingly generous terms to the guerillas. Those determined to fight to the bitter end became known as Bittereinders (I’m not even making that up), while those who accepted reconciliation were labeled Hensoppers – literally, “hands-uppers.”

The Anglo’s perceived brutality severely damaged their standing in the eyes of the rest of the world as well as provoking outrage and protests back home. The war became increasingly unpopular as it continued to drag on, prompting the British to offer increasingly generous terms to the guerillas. Those determined to fight to the bitter end became known as Bittereinders (I’m not even making that up), while those who accepted reconciliation were labeled Hensoppers – literally, “hands-uppers.”

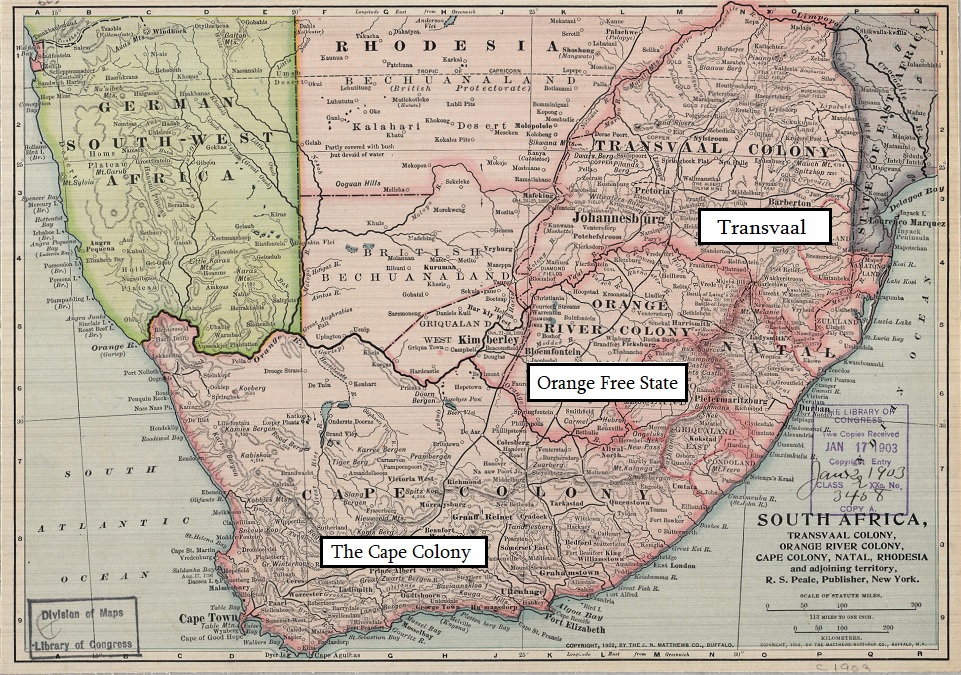

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of.

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of.