This one’s a little longer than I normally like – a fact which isn’t exactly helped by adding 54 words up front to tell you so. I wanted to wrap this one up, but couldn’t bring myself to cut more than I already have. For the #11FF actually plowing through these with me, my apologies

This one’s a little longer than I normally like – a fact which isn’t exactly helped by adding 54 words up front to tell you so. I wanted to wrap this one up, but couldn’t bring myself to cut more than I already have. For the #11FF actually plowing through these with me, my apologies

Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation — or any nation so conceived and so dedicated — can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

BUT –

This may be the most powerful word in the English language. This ‘but’, at least, is a BIG, BIG BUT. And it belongs to President Lincoln.

I like it, and I cannot lie.

I like it, and I cannot lie.

“Gary, you’re such a great guy. You’re funny, you’re smart, and it’s been such an amazing past four months together. Any girl would be lucky to have you as her boyfriend… BUT-“

You know what’s coming, don’t you?

“Ms. Terry, we appreciate your hard work over the past year and your creativity with kids. You’ve handled some tough circumstances as you prepared them for their CRTs… BUT-“

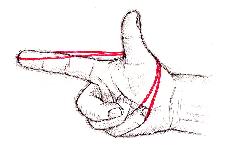

‘But’ can overturn everything that’s come before. Whatever follows is often MORE powerful as a result, like pulling back on the rubber band before letting it go. Here, Lincoln uses his big ‘but’ to take his message an entirely different direction suddenly and powerfully.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow — this ground.

What beautiful sentence structure. He’s already hit us with repeated uses of ‘dedicate’ in the opening segment. Either he needs a thesaurus, or he’s intentionally layering in a theme before becoming more specific with his thesis.

What beautiful sentence structure. He’s already hit us with repeated uses of ‘dedicate’ in the opening segment. Either he needs a thesaurus, or he’s intentionally layering in a theme before becoming more specific with his thesis.

In class, we stop to define ‘dedicate’, and I ask for examples of things commonly dedicated – a tree, a book, a building, a scholarship in someone’s memory. ‘Dedicate’ can be pretty intense, like the baby dedication I mentioned last time, or mostly fun, like requesting a song on the radio for Marcia Stiflewagon, who looks awkward in a dress but kinda hot in her weightlifting gear.

Then Lincoln takes it up a notch. ‘Consecrate’. We define this as well. There are fewer examples of things commonly ‘consecrated’ – sacramental bread, wine, marriages, etc. It’s getting’ all spiritual up in Gettysburg – and they were only about 90 seconds into his speech.

And there’s a third and final step.

We can’t ‘hallow’ this ground either. That’s a tough one. No one uses this word in normal conversation. Given some prodding, students will connect ‘Halloween,’ although they don’t generally know where that comes from either. Some reference Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – that kinda brushes the concept for which we’re reaching.

When I was a kid, every day during announcements we recited the Lord’s Prayer, right after the Pledge of Allegiance. (I know, I know – it was a different time and place, and no one thought much of it, at least not that I was aware.) And of course we used the King James version, which began like this:

“Our Father, which art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy name…”

The name of Jehovah (Yahweh) was so sacred, one did not commonly say it aloud. You don’t tug on Superman’s cape, you don’t draw cartoons of Mohammed, and you don’t speak this particular name of God lightly – let alone ‘in vain’. Like touching the Ark of the Covenant or entering the Holy of Holies without proper cleansing, some things were so divine as to be dangerous.

Holy can be serious business.

So we came here to dedicate this ground, and that’s fine. But really… we can’t. Can’t dedicate it. (*up a notch*) Can’t consecrate it. (*up another*) Can’t hallow this ground.

We’re suddenly in sanctified territory – and rather unexpectedly. Why, Mr. President? Why can’t we do this?

The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

This part is difficult for my kids. Even those who are Sunday-go-to-Meetin’ types don’t really do much super-sacred any more. We talk about what these ‘brave men’ must have done to ‘consecrate’ that ground. They came, they fought, they died, all for a hypothesis about men being created equal, according to Lincoln.

This part is difficult for my kids. Even those who are Sunday-go-to-Meetin’ types don’t really do much super-sacred any more. We talk about what these ‘brave men’ must have done to ‘consecrate’ that ground. They came, they fought, they died, all for a hypothesis about men being created equal, according to Lincoln.

All of this is true, and all important.

But more specifically, most of them shed their blood. They bled into the soil – literally. And in the Christian faith (for by now it’s obvious this is Lincoln’s chosen framework), blood has power.

In the Old Testament, sin and failure were purged through animal sacrifice. The rules regarding what you could and couldn’t do with blood were rather detailed. In the New, it was Jesus on the Cross who offers redemption. Subsequent discussions of this sacrifice often specifically reference the shedding of blood, and if you came back in time with me to that little church where I grew up, you’d find us singing about it all the time.

“Would you be free from your burden of sin? There’s POWER in the BLOOD, POWER in the BLOOD…”

“Would you be free from your burden of sin? There’s POWER in the BLOOD, POWER in the BLOOD…”

“Are you washed in the Blood? In the soul-cleansing blood of the Lamb?”

“What can wash away my sin? Nothing but the blood of Jesus…”

Lincoln is calling up the most sacred imagery of the Christian faith – one everyone in his audience understood and most practiced on at least a superficial level. He’s declaring the soil on which they stand – in which these men were now buried – to be ‘consecrated’ by the blood spilled there defending this hypothesis.

“We’re here with words, and songs, and good intentions, sure!” he says. “But they DIED here, violently and valiantly, for this cause. What in the world could we add with some WORDS?”

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

Did Lincoln know this was ironic when he said it? I have no idea.

So, Mr. President… why ARE we here?

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain –

That’s a mouthful, and the hardest part for students to memorize when they’re reciting it to the class for extra credit. Lincoln’s word-weaving turns the purpose of the occasion, the war, and the entire nation inside out – bringing to the foreground the ideals we still espoused, but had long since negated through abuse and neglect.

That’s a mouthful, and the hardest part for students to memorize when they’re reciting it to the class for extra credit. Lincoln’s word-weaving turns the purpose of the occasion, the war, and the entire nation inside out – bringing to the foreground the ideals we still espoused, but had long since negated through abuse and neglect.

These men died for something, and now continuing that something is on US. On YOU. The power of martyrdom multiplied by the thousands, and the obligations of a loved one’s final wishes, combined on sacred ground. Dedicated, dedicated, devotion, devotion, resolve not died in vain.

Put down your corn dogs and tiny Union flags, kids – the President just called us out. And he did it without actually saying anything we didn’t already agree with.

Baby ‘Merica was born 87 years ago, in Liberty, and dedicated to a hypothesis – that all men are created equal. In youth, it was noble and pure and full of the idealism captured in the Declaration of Independence – our national birth certificate. Growing pains brought complications, and it began compromising those ideals for the most pragmatic reasons… little realizing that such leaven almost always leavens the entire loaf.

And now, through war with ourselves, we’ve died. Many literally, the rest emotionally and spiritually. Blood has washed the ground, re-consecrating us and making possible the realization of that hypothesis – we CAN build and maintain a nation founded on the principle that all men are created equal.

that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom –

Lazarus, John Baptizing in the Jordan, Jesus emerging from the tomb – it’s all about the rebirth, baby. There’s a reason we hunt eggs (of all things) on Easter.

Lazarus, John Baptizing in the Jordan, Jesus emerging from the tomb – it’s all about the rebirth, baby. There’s a reason we hunt eggs (of all things) on Easter.

We were born once, but we ate the apple of vanity and compromise, and died. Now it’s time to be ‘born again’.

and that government of the people, by the people, for the people,

Which people?

WHICH PEOPLE? He never says it, but it couldn’t be more clear.

shall not perish from the earth.

For those of you who aren’t Sunday-go-to-Meetin’ types, things are different once you’re born again. You’re purified, more true to what you were created to be, and you don’t die a second time.

And you don’t keep it to yourself. You try to pass along the good news to others – that any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can in fact ‘long endure’.

Afterward: I couldn’t end on such a positive note without acknowledging my grief and disappointment where we are 150 years later after all of that. As the Israelites longed to go back to Egypt (for the onions, no less), as dogs return to their vomit and pigs to wallow in their mud, we seem to cling as a nation to the same vanity, hypocrisy, and violence which took us into that war. I don’t have an answer or wish to be a downer, but I couldn’t wrap up in good conscience without expressing that I love the speech, I love the ideals, I love the nation – but in so many ways we’re further than ever from what we proclaim to be. It hurts my innards to contemplate.

RELATED POST: The Gettysburg Address, Part One (After Everett)

RELATED POST: The Gettysburg Address, Part Two (Dedicated to a Proposition)

When I talk about this speech in workshops, I never know how much to assume teachers already know, or whether my ‘givens’ and their ‘givens’ are likely to be compatible. We cover so many different things in so many different ways… there’s very little we can assume to be universal in Social Studies content knowledge (or pedagogy, for that matter). And that’s OK.

When I talk about this speech in workshops, I never know how much to assume teachers already know, or whether my ‘givens’ and their ‘givens’ are likely to be compatible. We cover so many different things in so many different ways… there’s very little we can assume to be universal in Social Studies content knowledge (or pedagogy, for that matter). And that’s OK. Why do we call them our ‘fathers’? What makes someone a ‘father’?

Why do we call them our ‘fathers’? What makes someone a ‘father’? But Baby ‘Merica isn’t dedicated to God – at least according to Lincoln . (Don’t tell the Republicans!) It’s dedicated to an idea, a proposition – that all men are created equal.

But Baby ‘Merica isn’t dedicated to God – at least according to Lincoln . (Don’t tell the Republicans!) It’s dedicated to an idea, a proposition – that all men are created equal. Does that work? This… ‘all men are created equal’ – can you run a country based on that, or will it fail?

Does that work? This… ‘all men are created equal’ – can you run a country based on that, or will it fail? This, incidentally, would have been news to many of the men being honored that day. Most thought they were fighting for the Constitution, the Union, maybe their states or families, or just because they were annoyed with the people on the other side. A few sensed the long game, but it was hardly the norm.

This, incidentally, would have been news to many of the men being honored that day. Most thought they were fighting for the Constitution, the Union, maybe their states or families, or just because they were annoyed with the people on the other side. A few sensed the long game, but it was hardly the norm. The Battle of Gettysburg was a three-day conflagration resulting from Robert E. Lee’s second and final attempt to bring the Civil War into the North, in hopes citizens therein would tire of the fighting and tell their elected leaders – Lincoln in particular – to knock it off.

The Battle of Gettysburg was a three-day conflagration resulting from Robert E. Lee’s second and final attempt to bring the Civil War into the North, in hopes citizens therein would tire of the fighting and tell their elected leaders – Lincoln in particular – to knock it off. The same month saw the fall of Vicksburg in the Western Theater, the rapidly growing acceptance of black soldiers in the Union after Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick martyred themselves in the attack on Fort Wagner, and the pivotal Battle of Honey Springs in Indian Territory (the ‘Gettysburg of the West’, according to my state-approved Oklahoma History textbook).

The same month saw the fall of Vicksburg in the Western Theater, the rapidly growing acceptance of black soldiers in the Union after Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick martyred themselves in the attack on Fort Wagner, and the pivotal Battle of Honey Springs in Indian Territory (the ‘Gettysburg of the West’, according to my state-approved Oklahoma History textbook). It wasn’t decent, and it certainly wasn’t healthy.

It wasn’t decent, and it certainly wasn’t healthy. President Lincoln was invited as well, but unlike today the presence of the President did not automatically presume he would become central to everything else. Lincoln’s role was to give some closing comments before the final song or prayer – not to upstage Everett. While it’s likely people anticipated more than the two or three minutes it would have taken for him to deliver what became known as his “Gettysburg Address,” they certainly weren’t expecting anything particularly extensive either. That wasn’t why he was there.

President Lincoln was invited as well, but unlike today the presence of the President did not automatically presume he would become central to everything else. Lincoln’s role was to give some closing comments before the final song or prayer – not to upstage Everett. While it’s likely people anticipated more than the two or three minutes it would have taken for him to deliver what became known as his “Gettysburg Address,” they certainly weren’t expecting anything particularly extensive either. That wasn’t why he was there. The ‘holy inspiration’

The ‘holy inspiration’

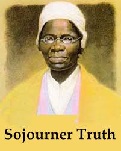

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the Convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity:

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the Convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity: Twelve years later, Frances Gage – a well-known reformer, abolitionist, and feminist in her own right – recounted the event somewhat differently. Gage was present at the convention, and was in fact the President to whom Truth addressed her initial request to speak. The version Gage recorded has become much better known, and is the one most often replicated, laminated, and recited when we speak of Truth today.

Twelve years later, Frances Gage – a well-known reformer, abolitionist, and feminist in her own right – recounted the event somewhat differently. Gage was present at the convention, and was in fact the President to whom Truth addressed her initial request to speak. The version Gage recorded has become much better known, and is the one most often replicated, laminated, and recited when we speak of Truth today. Maybe it was impossible to transfer the effect to paper, but Gage could try. I submit that she altered the facts in order to capture the truth. Recounting the event was inadequate, so she revamped it in order to get closer to what actually happened experientially. In her mind, I believe, the most important element of Truth’s speech that night was not the transcript, but the message and its impact.

Maybe it was impossible to transfer the effect to paper, but Gage could try. I submit that she altered the facts in order to capture the truth. Recounting the event was inadequate, so she revamped it in order to get closer to what actually happened experientially. In her mind, I believe, the most important element of Truth’s speech that night was not the transcript, but the message and its impact. Christopher Columbus has become a controversial figure in recent years. For some reason, the Native population of this grand land refuses to get overly excited about the man who first brought enslavement, disease, and near genocide to their ancestors. The basic mythology of his story has proven rather tenacious, however, even as his status as someone deserving their own holiday has come into dispute.

Christopher Columbus has become a controversial figure in recent years. For some reason, the Native population of this grand land refuses to get overly excited about the man who first brought enslavement, disease, and near genocide to their ancestors. The basic mythology of his story has proven rather tenacious, however, even as his status as someone deserving their own holiday has come into dispute. This brief oration is arguably the most important speech of the 19th Century – maybe in all of American history. In approximately three minutes, President Lincoln deftly redefined the purpose and scope of the Civil War and charged his audience and all future Americans with the “great task remaining before us” of extending full American-ness to all people, as apparently both the Founders and the dead soldiers being commemorated that day had intended – although that would have come as news to many of them, had they been alive to hear it.

This brief oration is arguably the most important speech of the 19th Century – maybe in all of American history. In approximately three minutes, President Lincoln deftly redefined the purpose and scope of the Civil War and charged his audience and all future Americans with the “great task remaining before us” of extending full American-ness to all people, as apparently both the Founders and the dead soldiers being commemorated that day had intended – although that would have come as news to many of them, had they been alive to hear it. Little wonder, looking at this speech a masterpiece of imagery, language, and manipulation for the good of mankind, and in so few words – that we can almost SEE the white dove descending from heaven to whisper the words in Lincoln’s ear. Less romantic is the idea that good writing – like good anything – is more often the product of years of effort, study, and practice.

Little wonder, looking at this speech a masterpiece of imagery, language, and manipulation for the good of mankind, and in so few words – that we can almost SEE the white dove descending from heaven to whisper the words in Lincoln’s ear. Less romantic is the idea that good writing – like good anything – is more often the product of years of effort, study, and practice. Everett did indeed speak for somewhere around three hours, but that wasn’t considered excessive, nor was it tiring to hear. This was a pre-Xbox, pre-Facebook, pre-RockfordFiles nation. Life was in many ways slower and oration was high entertainment when done well – and Everett was the Paul McCartney of speechifyin’. A bit on the long side of his peak, he was nevertheless legendary for leading the audience through whatever rhetorical journey he chose, and by all accounts that day he was a master.

Everett did indeed speak for somewhere around three hours, but that wasn’t considered excessive, nor was it tiring to hear. This was a pre-Xbox, pre-Facebook, pre-RockfordFiles nation. Life was in many ways slower and oration was high entertainment when done well – and Everett was the Paul McCartney of speechifyin’. A bit on the long side of his peak, he was nevertheless legendary for leading the audience through whatever rhetorical journey he chose, and by all accounts that day he was a master.

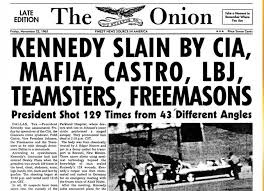

The idea that 9/11 was an inside job or that MLK was killed by the FBI is disturbing enough, but the alternatives are worse – that individuals or small groups of people, without the knowledge or control of those tasked with keeping us safe, did the worst of big bad things no one could anticipate or stop. We are creatures who want desperately to see order in our surroundings, and to claim some element of control over even the least controllable parts of our lives. A massive conspiracy by a large, powerful organization or sly government entity may be loathsome, but it’s not quite so terrifying as the unpredictability of the alternatives.

The idea that 9/11 was an inside job or that MLK was killed by the FBI is disturbing enough, but the alternatives are worse – that individuals or small groups of people, without the knowledge or control of those tasked with keeping us safe, did the worst of big bad things no one could anticipate or stop. We are creatures who want desperately to see order in our surroundings, and to claim some element of control over even the least controllable parts of our lives. A massive conspiracy by a large, powerful organization or sly government entity may be loathsome, but it’s not quite so terrifying as the unpredictability of the alternatives.