Three Big Things

1. The Santeria religion includes animal sacrifices as part of many rituals. These sacrifices are essential to both believers and their deities.

2. When the Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye announced its plans to build facilities in the city of Hialeah, Florida, city officials quickly moved to outlaw animal sacrifice for any reason – except for just about every other reason one might kill an animal, in which case it was still OK. Just not for the Santeria.

3. The Supreme Court found this violated the Free Exercise Clause by targeting specific religious behaviors without adequate justification, neutral application, or reasonable effort to accommodate the beliefs of the Santeria.

Background

Santeria is one of those religions that the folks most likely to demand more “freedom of religion” in the United States don’t actually mean to include.

Its roots are African, mixed with elements of Catholicism and perhaps a few other things as well. It is thus a prime example of “syncretism” (cultural mixing) – one of those fancy terms you no doubt recall from your world history class in high school. Thanks to the all-expense paid vacations offered to African natives by European powers prior to the mid-nineteenth century, it spread quickly to the Caribbean region and parts of the United States. It’s impossible to gauge actual numbers, of course – there were no official surveys regarding the preferred belief systems of slaves or anything.

For many years, Santeria remained largely “underground” in the U.S. Most adherents were people of color, many descended from former slaves or recent immigrants, and they no doubt had a pretty good idea how society would respond to such an “African”-flavored faith. Like many other elements of Black culture historically, many found it best to remain under white radar whenever possible.

Santeria remained particularly strong in Cuba, however, meaning it eventually carved out a presence in Florida as well, along with other scattered enclaves across the country. Membership has become slightly more diverse, with a noticeable minority of white folks and an Asian American or two. It’s not exactly “mainstream,” but neither is it totally obscure – at least from a statistical perspective.

Santeria is a very hands-on, get involved religion – far closer to Latin-flavored Catholicism than upper crust Protestantism. Its adherents (and no, they’re not called “Santerians”) often have alters in their homes on which they place flowers, cake, rum, or cigars to keep the gods happy. The “gods” in this case are the Orishas – powerful, but not omnipotent beings. Orishas are often conflated with or represented by various Catholic saints, each of whom has a “specialty” of sorts when it comes to divine intervention. Somewhat like the Hindu pantheon, Orishas are both distinct entities and manifestations or reflections of the same higher (or highest) power.

Spiritual truths don’t always follow worldly logic, after all.

What sets Santeria apart – at least in modern times – is the role of animal sacrifice. Historically, the ritual slaughter of various critters as offerings to the gods is pretty standard stuff. The Jews of the Old Testament are the most familiar example, but it was also common among the Greeks, Romans, Celts, Norse, Egyptians, and numerous other cultures. Christians echo the tradition by symbolically drinking of the blood and eating the flesh of the Son of God, thus maintaining the ritual with less clean-up afterwards. Islam rejects the “blood for favors or forgiveness” element and retains a single annual sacrifice of thankfulness each year during Eid al-Adha.

But in Santeria, sacrifices are far more old school. The relationships of believers and Orishas is symbiotic. Worshippers ask for assistance in fulfilling their divinely-approved destinies, and in exchange they perform the appropriate rituals. Acceptable sacrifices include various foods, drinks, and pretty things, but for big stuff – births, marriages, funerals, curing illness, confirming new members, etc. – animal slaughter is essential. Typical critters include chickens, doves, ducks, guinea pigs, goats, sheep, and turtles. For many (but not all) rituals, the animals are cooked and eaten by the community afterwards – a kind of “dining with the gods” thing. It’s not all just about animal sacrifices, of course. Drumming, dancing, speaking to the spirits, and the like, are usually in the mix as well. It’s interactive, both in terms of believer-to-believer and mortals-to-gods. The Orishas take care of the faithful, and in turn, they subsist on the rituals and sacrifices offered by faithful mortals. Without them, the Orishas would perish.

The Conflict

In 1987, the Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, led by Italero (“Priest”) Ernesto Pichardo, leased some land in Hialeah, Florida, and began securing the appropriate permits to establish a house of worship there. Santeria doesn’t generally have its own buildings, but this particular assembly hoped to start their own school, a cultural center, and a museum on site as well. Their stated goal was to bring Santeria out of the shadows and into the open, welcoming the community to learn more about them while providing their “congregation” with the same sort of facilities as any other mainstream religion.

Unfortunately, not all members of the surrounding community embraced this wonderful expansion of multiculturalism. Many, in fact, lost their proverbial minds. The Hialeah City Council began holding emergency meetings in which it was resolved that they’d find some way to shut this nonsense down. As community members lined up to voice their disapproval, many city officials simply couldn’t contain themselves and proclaimed that good Christian communities wouldn’t stand for this outrageous pagan stuff because America and democracy and gross-they-kill-chickens! One city councilman insisted with absolutely zero sense of irony that allowing Santeria to be practiced in their city was “in violation of everything this country stands for.” Another supported banning Santeria because he was certain the Bible didn’t approve of animal sacrifice.

I’ll give you a moment to process that one.

In short, the city was certain that Jesus would certainly never tolerate anyone who broke with the dominant religious beliefs of his day – and neither should Florida.

When it came time to actually commit words to paper, some effort was made to keep official rhetoric confined to the plausibly constitutional, framing the city’s objections as part of a larger, perfectly sensible policy against “certain religions” which might choose “to engage in practices which are inconsistent with public morals, peace, or safety.” As a body, the council declared that the “City reiterates its commitment to a prohibition against any and all acts of any and all religious groups which are inconsistent with public morals, peace, or safety.”

Put that way, it almost sounded reasonable.

Without mentioning Santeria or the Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye by name, the city council passed an emergency ordinance which repeated the state of Florida’s existing animal cruelty laws and clarified that these very much applied in Hialeah – as if perhaps not everyone was aware of how “state laws” worked. Finding this insufficient, but realizing there were limits as to how far the city could go in creating its own new criminal statues, they asked the state’s attorney general to get involved. He replied that existing Florida law prohibited the “unnecessary” killing of animals, which he defined as “done without any useful motive, in a spirit of wanton cruelty or for the mere pleasure of destruction without being in any sense beneficial or useful to the person killing the animal.” This included “ritual sacrifice of animals for purposes other than food consumption.”

In other words, according to Florida’s Attorney General, Hialeah could pass all the laws it liked to support the prohibition. Before the year was out, the city council passed several new ordinances prohibiting animal sacrifice within city limits, whether the flesh was eaten afterwards or not.

It’s worth noting the implicit assumption that religious rituals are by default lacking in “useful motive” and are not “in any sense beneficial or useful.” State and local lawmakers were careful to exempt all sorts of other reasons one might kill an animal – slaughterhouses and butchers were exempt, as were those hunting or fishing for sport or who raised a few small animals for food. It was OK to kill household pests or put down strays at the local veterinary clinic or kill an animal in self-defense. In fact, the law allowed almost anyone to kill any animals for any reason except for the Santeria and their whole “animal sacrifice” thing – all without actually admitting on paper that’s what it was designed to do.

The Santeria objected, and eventually the case worked its way up to the Supreme Court.

Evolving Precedents

Way back in Reynolds v. United States (1879), the Court had ruled that it was acceptable for government to ban polygamy despite the impact this had on the practices of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (aka, “Mormons”). The Court acknowledged that marriage had a “sacred” element but noted that it was nevertheless typically regulated by secular laws in most civilized societies. You may believe whatever you like in a free country, the majority explained, but that doesn’t mean you can circumvent reasonable secular regulations based on those beliefs.

A few years later, in Davis v. Beason (1890), the Court validated state laws which prevented citizens from voting unless they were willing to swear they neither supported nor participated in polygamy. The majority opinion by Justice Stephen Field referred to polygamy as a violation of “the laws of all civilized and Christian countries” and said it tended to “destroy the purity of the marriage relation” as well as “degrade woman and… debase man.” Polygamy was gross and wrong and they should (literally) lock you up for even talking about it.

Once Justice Field had gotten some of the outrage out of his system, he was able to dial back his rhetoric enough to summarize the Court’s central point:

It was never intended or supposed that the {First} amendment could be invoked as a protection against legislation for the punishment of acts inimical to the peace, good order, and morals of society… However free the exercise of religion may be, it must be subordinate to the criminal laws of the country, passed with reference to actions regarded by general consent as properly the subjects of punitive legislation.

In other words, just as in Reynolds a decade before, the Court drew a line between what individuals were allowed to believe and what they were allowed to do. (The fact that the laws in question in Davis required citizens to deny specific beliefs in order to vote was thus both validated and ignored at the same time.)

Fast-forward to the early 1960s, right around the same time the Supreme Court was bullying God out of schools, allowing people to marry outside their race, and generally destroying the morality of an otherwise holy and prosperous people. Once again, some wacky fringe religion was making things difficult for real Americans.

Adele Sherbert was a Seventh-Day Adventist. The Adventists believe that God commanded man to rest on the Sabbath, which a glance at any wall calendar or daily pill dispenser will confirm is Saturday. She was fired and then denied unemployment for refusing to work on Saturdays. This rule did not apply to those unwilling to work on Sundays however – because church and stuff.

In Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Court ruled that the government can only restrict free exercise if the rules and procedures involved have been narrowly tailored to fulfill an essential state interest and with the minimum possible disruption to religious beliefs or rituals. Offering unemployment benefits to Sherbert wouldn’t be favoring her religion over others; it would merely be treating it the same as others with minor adjustments in the details. That’s the goal of the Free Exercise Clause, explained the Court.

Sherbert was a substantial shift in how the Court balanced secular law and religious freedom. Government at all levels was now expected to make every effort to accommodate religious beliefs or to restrict them as minimally as possible when applying neutral and essential rules and procedures. The state must have a “compelling interest” in play to justify violating free exercise.

A generation later, in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990), the Court again shifted its perspective on free exercise. In this case, Alfred Smith was fired from his job as a drug rehabilitation counselor because his employer discovered he used peyote (a hallucinogenic) as part of his Native American religious rituals. The state denied him unemployment benefits because he’d been dismissed for “work-related misconduct.” Smith’s attorneys argued that based on the standard established in Sherbert, his use of peyote for religious purposes should be exempt from otherwise general rules prohibiting drug use.

The Court decided to cut loose the “compelling interest” test of Sherbert and determined instead that generally applicable laws which only incidentally impact religious behavior (i.e., they’re clearly not designed to target it) do not violate the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. The majority also drew a critical distinction between the two situations. Sherbert had been denied unemployment because the state refused to make minor policy adjustments to accommodate her religious beliefs. Smith was fired and denied unemployment for committing a felony for which he hoped to secure a religious exemption.

The Court also added another odd little wrinkle to the mix to be considered moving forward. Many free exercise cases involved related rights as well – freedom of speech and the press, parental rights over their children, etc. Smith’s case did not. In “hybrid” cases, the Court would generally use the same “strict scrutiny” standard requiring government to show a “compelling interest” in infringing on individual beliefs. In a “pure” case, however, the government need only show that the laws or policies in question are legitimate roles of government and have been applied neutrally. In the case of Smith’s peyote use, this was clearly the case.

Smith specifically rejected the premise that government was required to show a “compelling interest” whenever general laws substantially interfered with religious practices.

The Decision

Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for a unanimous Court in favor of the Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye. Or, rather, the justices unanimously found in favor of the church – although few of them agreed entirely as to why. (Apparently, religious freedom in the face of government regulation can be a sticky subject.) The Court was unified enough, however, to establish several clear takeaways from the case.

The Court acknowledged that the government may sometimes put burdens on religious practices with legislation that doesn’t target those practices but nevertheless impacts them. (A church who promoted human sacrifice or driving as fast as possible wouldn’t get exemptions from general laws prohibiting such things.)

The problem was that the city’s ordinances weren’t neutral. They didn’t even do a very good job of pretending they were. While state law already prohibited some animal slaughter, Hialeah officials clearly sought to prohibit this specific religious practice – they responded to community concerns that way, debated legislation that way, and crafted the specific language of local statutes that way. They’d essentially “gerrymandered” the rules to target the practices and beliefs of one specific religious organization. That’s a big constitutional no-no.

(It’s worth noting that both Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Rehnquist dissented from this part – they objected to the use of legislative motivation as a factor in determining the constitutionality of specific acts of legislation. As the Court has become more conservative in recent years, it’s become increasingly comfortable setting aside obvious context and loudly proclaimed intent in order to justify some rather counterintuitive outcomes based on technicalities or the “letter of the laws” in question.)

When laws aren’t clearly neutral, or are not applied in a neutral way, the government body making and enforcing those rules needs to be able to demonstrate a “compelling interest” which justifies the necessity of such rules and must show that it’s “narrowly tailored” its actions to interfere with religious as little as possible while still accomplishing its goals. In the case of Hialeah and the state of Florida, the laws in question didn’t consistently prioritize public health and safety (the supposed reason for passing them in the first place), and when they did address public health and safety, they were often unnecessarily broad. In other words, they were both too general and too limited all at the same time.

That happens when you’re trying to fight the even ooga-booga men and their devil faith but you have to distort and twist everything to get there… so the “truth” can win.

In short, the efforts of the city of Hialeah to ban Santeria violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Whenever general laws end up infringing on religious beliefs or practices, they are subject to what the Court calls “close scrutiny” to determine whether or not such laws are both neutral (applying equally to everyone regardless of religious factors) and necessary (serving a legitimate government goal with as little interference as possible in religious matters). These laws were neither.

There Ought To Be A Law

While the Lukumi Babalu case was working its way through the system, Congress was up in arms about the Court’s decision in Employment Division v. Smith and passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993. Setting aside the unnecessarily dramatic title, this legislation required courts to use “strict scrutiny” in all free exercise cases and mandated the revival of the “compelling interest” standard from Sherbert. The goal was to make it more difficult in general for government at any level to enforce general rules and regulations against religious groups or individuals – to essentially grant religious behavior a partial exemption from the laws governing everything and everyone else.

The Court invalidated most of the RFRA in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997) based on shut-up-don’t-tell-us-how-to-do-our-job. Congress tried again with the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) of 2000, and this time most of what they wanted seemed to stick. In matters related to prisoners’ religious rights or religious institutions wanting to ignore zoning regulations, historical preservation statutes, parking requirements, etc., government has to meet a much higher standard before being allowed to infringe on free exercise by treating people or institutions of faith like everyone else.

It’s quite doubtful Congress had Santeria in mind while crafting RFRA or its sequel, but their respective impacts certainly complement one another. RLUIPA is still in effect, and Lukumi Babalu is still cited regularly in cases involving general laws or practices which in some way interfere with sincere religious choices. (It was referenced in both 2022 cases involving religion in schools – Carson v. Makin and Kennedy v. Bremerton – although not as the primary foundation for either decision.)

Generally speaking, any governmental action which infringes on religious behaviors or beliefs must be “narrowly tailored” to accomplish legitimate government goals and applied neutrally. In recent years, the Court has come to conflate this with a constitutional requirement that government overtly support religion in certain instances – that anything short of that is, in fact, infringes on free exercise. Just how far this stretches and in what specific situations it does or doesn’t apply is still being… sorted out.

We’ll see how it goes.

Excerpts from Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah (1993), Majority Opinion by Justice Anthony Kennedy

{Edited for Readability}

The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, which has been applied to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment (see Cantwell v. Connecticut, 1940), provides that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…” … Although the practice of animal sacrifice may seem abhorrent to some, “religious beliefs need not be acceptable, logical, consistent, or comprehensible to others in order to merit First Amendment protection” (Thomas v. Review Board of Indiana Employment Security Division, 1981). Given the historical association between animal sacrifice and religious worship, petitioners’ assertion that animal sacrifice is an integral part of their religion “cannot be deemed bizarre or incredible” (Frazee v. Illinois Dept. of Employment Security, 1989). Neither the city nor the courts below, moreover, have questioned the sincerity of petitioners’ professed desire to conduct animal sacrifices for religious reasons…

In addressing the constitutional protection for free exercise of religion, our cases establish the general proposition that a law that is neutral and of general applicability need not be justified by a compelling governmental interest even if the law has the incidental effect of burdening a particular religious practice (Employment Division, Dept. of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith, 1990). Neutrality and general applicability are interrelated, and, as becomes apparent in this case, failure to satisfy one requirement is a likely indication that the other has not been satisfied… These ordinances fail to satisfy {either}…

At a minimum, the protections of the Free Exercise Clause pertain if the law at issue discriminates against some or all religious beliefs or regulates or prohibits conduct because it is undertaken for religious reasons…

There are, of course, many ways of demonstrating that the object or purpose of a law is the suppression of religion or religious conduct. To determine the object of a law, we must begin with its text, for the minimum requirement of neutrality is that a law not discriminate on its face…

We reject the contention advanced by the city that our inquiry must end with the text of the laws at issue. Facial neutrality is not determinative. The Free Exercise Clause, like the Establishment Clause, extends beyond facial discrimination. The Clause “forbids subtle departures from neutrality” (Gillette v. United States, 1971) and “covert suppression of particular religious beliefs” (Bowen v. Roy, 1986). Official action that targets religious conduct for distinctive treatment cannot be shielded by mere compliance with the requirement of facial neutrality. The Free Exercise Clause protects against governmental hostility which is masked as well as overt. “The Court must survey meticulously the circumstances of governmental categories to eliminate, as it were, religious gerrymanders” (Walz v. Tax Commission of New York City, 1970).

The record in this case compels the conclusion that suppression of the central element of the Santeria worship service was the object of the ordinances…

Resolution 87-66, adopted June 9, 1987, recited that “residents and citizens of the City of Hialeah have expressed their concern that certain religions may propose to engage in practices which are inconsistent with public morals, peace or safety,” and “reiterated” the city’s commitment to prohibit “any and all such acts of any and all religious groups.” No one suggests, and on this record it cannot be maintained, that city officials had in mind a religion other than Santeria.

It becomes evident that these ordinances target Santeria sacrifice when the ordinances’ operation is considered. Apart from the text, the effect of a law in its real operation is strong evidence of its object… The subject at hand does implicate, of course, multiple concerns unrelated to religious animosity, for example, the suffering or mistreatment visited upon the sacrificed animals and health hazards from improper disposal. But the ordinances when considered together disclose an object remote from these legitimate concerns. The design of these laws accomplishes instead a “religious gerrymander” (Walz), an impermissible attempt to target petitioners and their religious practices…

We begin with Ordinance 87-71. It prohibits the sacrifice of animals, but defines sacrifice as “to unnecessarily kill… an animal in a public or private ritual or ceremony not for the primary purpose of food consumption.” The definition excludes almost all killings of animals except for religious sacrifice, and the primary purpose requirement narrows the proscribed category even further, in particular by exempting kosher slaughter… The net result of the gerrymander is that few if any killings of animals are prohibited other than Santeria sacrifice…

Operating in similar fashion is Ordinance 87-52, which prohibits the “possession, sacrifice, or slaughter” of an animal with the “intent to use such animal for food purposes.” … The ordinance exempts, however, “any licensed food establishment” with regard to “any animals which are specifically raised for food purposes” … Again, the burden of the ordinance, in practical terms, falls on Santeria adherents but almost no others… A pattern of exemptions parallels the pattern of narrow prohibitions. Each contributes to the gerrymander.

Ordinance 87-40 incorporates the Florida animal cruelty statute… The city claims that this ordinance is the epitome of a neutral prohibition. The problem, however, is the interpretation given to the ordinance by respondent and the Florida attorney general. Killings for religious reasons are deemed unnecessary, whereas most other killings fall outside the prohibition. The city, on what seems to be a per se basis, deems hunting, slaughter of animals for food, eradication of insects and pests, and euthanasia as necessary… Indeed, one of the few reported Florida cases decided under {this same state law} concludes that the use of live rabbits to train greyhounds is not unnecessary… Respondent’s application of the ordinance’s test of necessity devalues religious reasons for killing by judging them to be of lesser import than nonreligious reasons. Thus, religious practice is being singled out for discriminatory treatment.

We also find significant evidence of the ordinances’ improper targeting of Santeria sacrifice in the fact that they proscribe more religious conduct than is necessary to achieve their stated ends…

The legitimate governmental interests in protecting the public health and preventing cruelty to animals could be addressed by restrictions stopping far short of a fiat prohibition of all Santeria sacrificial practice. If improper disposal, not the sacrifice itself, is the harm to be prevented, the city could have imposed a general regulation on the disposal of organic garbage. It did not do so. Indeed, counsel for the city conceded at oral argument that, under the ordinances, Santeria sacrifices would be illegal even if they occurred in licensed, inspected, and zoned slaughterhouses. Thus, these broad ordinances prohibit Santeria sacrifice even when it does not threaten the city’s interest in the public health…

With regard to the city’s interest in ensuring the adequate care of animals, regulation of conditions and treatment, regardless of why an animal is kept, is the logical response to the city’s concern, not a prohibition on possession for the purpose of sacrifice. The same is true for the city’s interest in prohibiting cruel methods of killing… If the city has a real concern…, the subject of the regulation should be the method of slaughter itself, not a religious classification that is said to bear some general relation to it…

In determining if the object of a law is a neutral one under the Free Exercise Clause, we can also find guidance in our equal protection cases… Here, as in equal protection cases, we may determine the city council’s object from both direct and circumstantial evidence (Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 1977). Relevant evidence includes, among other things, the historical background of the decision under challenge, the specific series of events leading to the enactment or official policy in question, and the legislative or administrative history, including contemporaneous statements made by members of the decision-making body…

That the ordinances were enacted “because of,” not merely “in spite of,” their suppression of Santeria religious practice is revealed by the events preceding their enactment… The minutes and taped excerpts of the June 9 session, both of which are in the record, evidence significant hostility exhibited by residents, members of the city council, and other city officials toward the Santeria religion and its practice of animal sacrifice. The public crowd that attended the June 9 meetings interrupted statements by council members critical of Santeria with cheers and the brief comments of Pichardo {the church’s primary religious leader} with taunts. When Councilman Martinez, a supporter of the ordinances, stated that in prerevolution Cuba “people were put in jail for practicing this religion,” the audience applauded.

Other statements by members of the city council were in a similar vein. For example, Councilman Martinez, after noting his belief that Santeria was outlawed in Cuba, questioned: “If we could not practice this religion in our homeland, why bring it to this country?” Councilman Cardoso said that Santeria devotees at the Church “are in violation of everything this country stands for.” Councilman Mejides indicated that he was “totally against the sacrificing of animals” and distinguished kosher slaughter because it had a “real purpose.” The “Bible says we are allowed to sacrifice an animal for consumption,” he continued, “but for any other purposes, I don’t believe that the Bible allows that.” …

Various Hialeah city officials made comparable comments…

In sum, the neutrality inquiry leads to one conclusion: The ordinances had as their object the suppression of religion…

The principle that government, {even} in pursuit of legitimate interests, cannot in a selective manner impose burdens only on conduct motivated by religious belief is essential to the protection of the rights guaranteed by the Free Exercise Clause… In this case we need not define with precision the standard used to evaluate whether a prohibition is of general application, for these ordinances fall well below the minimum standard necessary to protect First Amendment rights.

The Free Exercise Clause commits government itself to religious tolerance, and upon even slight suspicion that proposals for state intervention stem from animosity to religion or distrust of its practices, all officials must pause to remember their own high duty to the Constitution and to the rights it secures. Those in office must be resolute in resisting importunate demands and must ensure that the sole reasons for imposing the burdens of law and regulation are secular. Legislators may not devise mechanisms, overt or disguised, designed to persecute or oppress a religion or its practices. The laws here in question were enacted contrary to these constitutional principles, and they are void.

Stomping Decisis (Introduction)

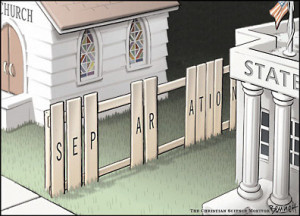

Stomping Decisis (Introduction) Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.

Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.